Two Rebel Haversacks in the Florida Confederate Museum Collection

By Fred Adolphus, April 12, 2014

By Fred Adolphus, April 12, 2014

In October 2013, I had the privilege of viewing the phenomenal “Florida Confederate Museum” collection of Richard Ferry. This eclectic collection held some of the most amazing Confederate artifacts I have seen. I will include many of them in subsequent articles, but for the time being I want to share with readers two interesting Confederate haversacks. One is a typical, mass-produced army haversack from either Virginia or North Carolina. The other is a custom made product captured by Federal soldiers at the Battle of Olustee, Florida.

The quartermaster-made haversack comes from the Goulding family. At least two Goulding brothers served in the Army of Northern

Virginia. Both were from Darien, Georgia. Francis R. Goulding served with the Jeff Davis Legion, Mississippi Cavalry, and ended the war in a hospital in Charlotte, North Carolina. His brother, C.H. Goulding, served with the 8th Georgia Infantry. C.H. Goulding died in General Hospital 21, Richmond, Virginia, December 24, 1862 of “remittent fever” (caused by gonorrhea). The collection has a number of objects from the Goulding family, to include Francis’s vest fashioned from a Tait jacket. The vest has strong provenance to Francis, but the haversack’s story is murkier, since family legend attributes it to C.H. The connection with C.H. is tenuous, because it is unlikely that the hospital would have returned a haversack to the family in 1862, unless it contained other personal items. Even then, sending this home would have been an extravagance that stretches plausibility. It is more likely that the haversack belonged to Francis, and that he brought it home with his vest and other Confederate memorabilia. This makes sense to me, because the haversack is clean and in good

condition. It is likely that Francis got this fresh haversack while he was in the hospital in Charlotte, and the war ended before it saw any heavy field use. In any case, the haversack is an amazing example of a cheap, simple, mass-produced Confederate haversack, typical

of what Southern soldiers received from the quartermaster.

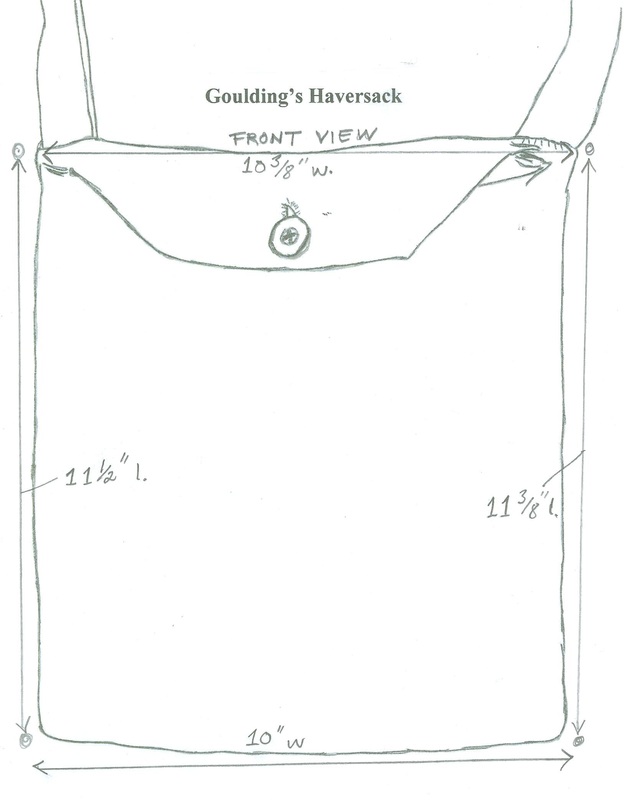

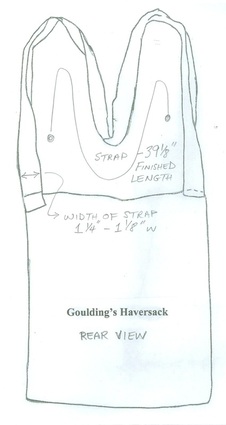

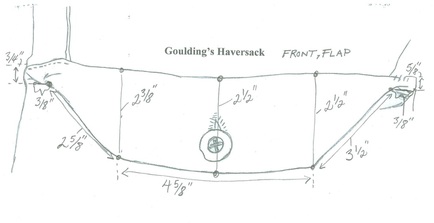

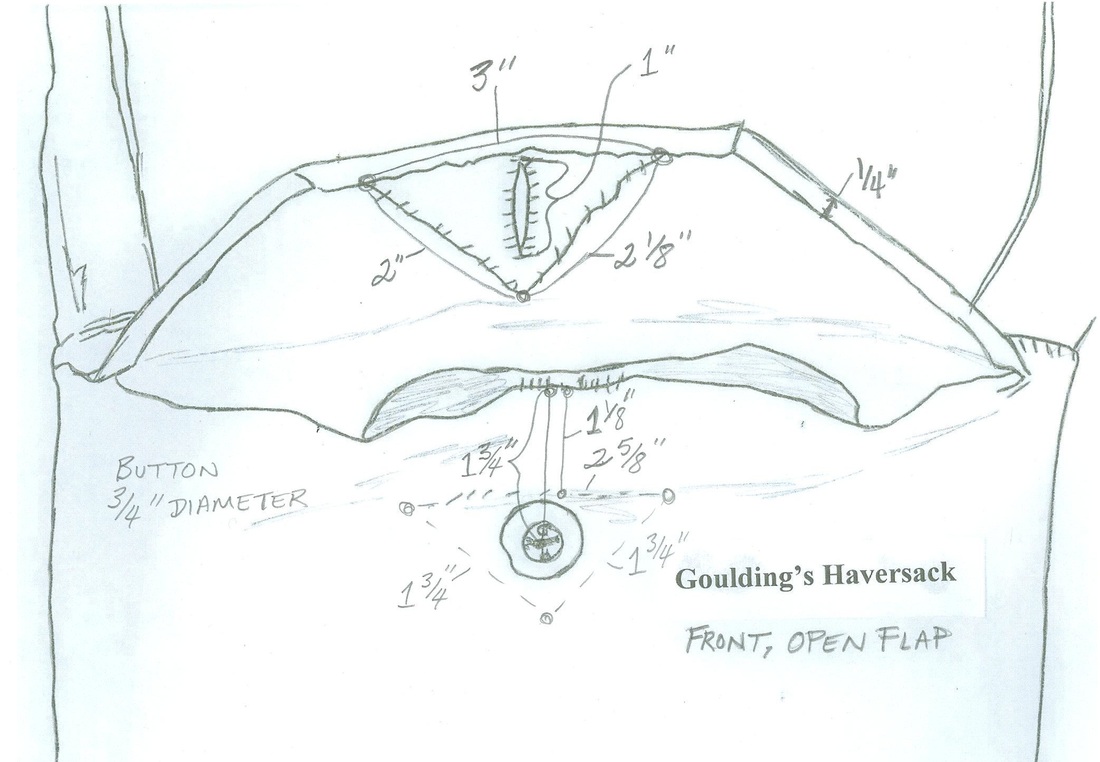

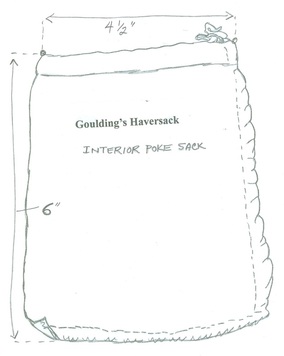

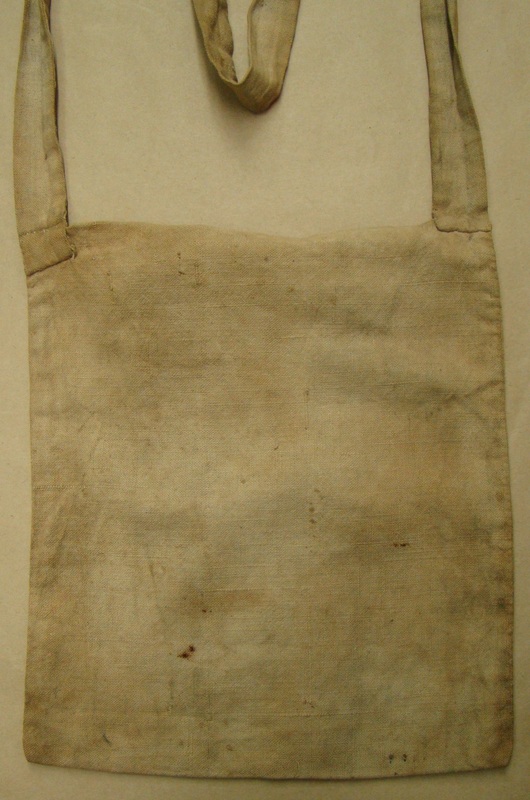

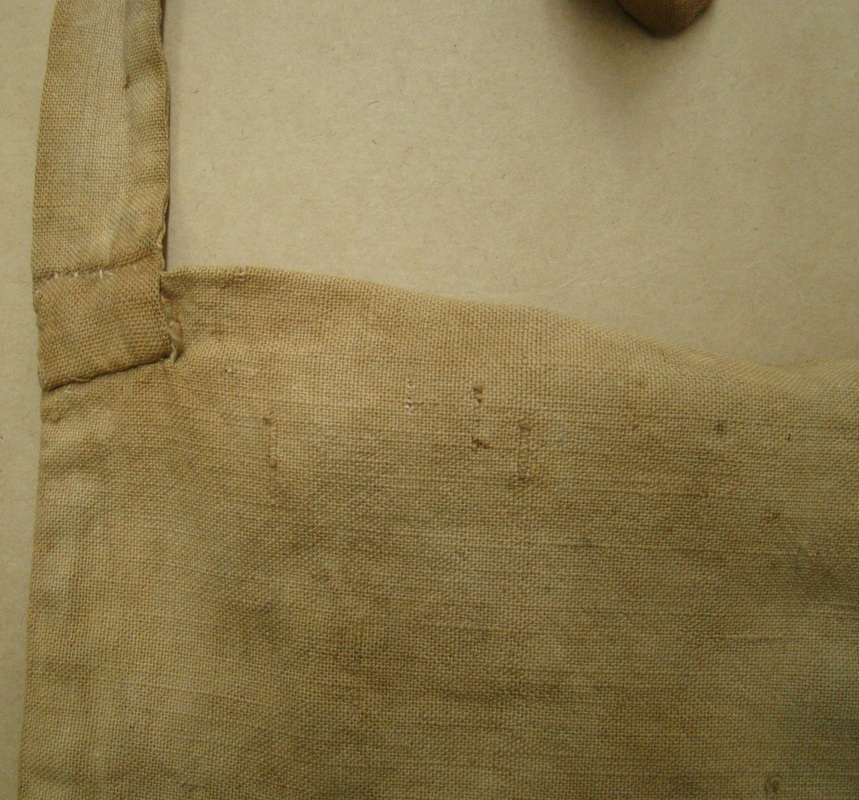

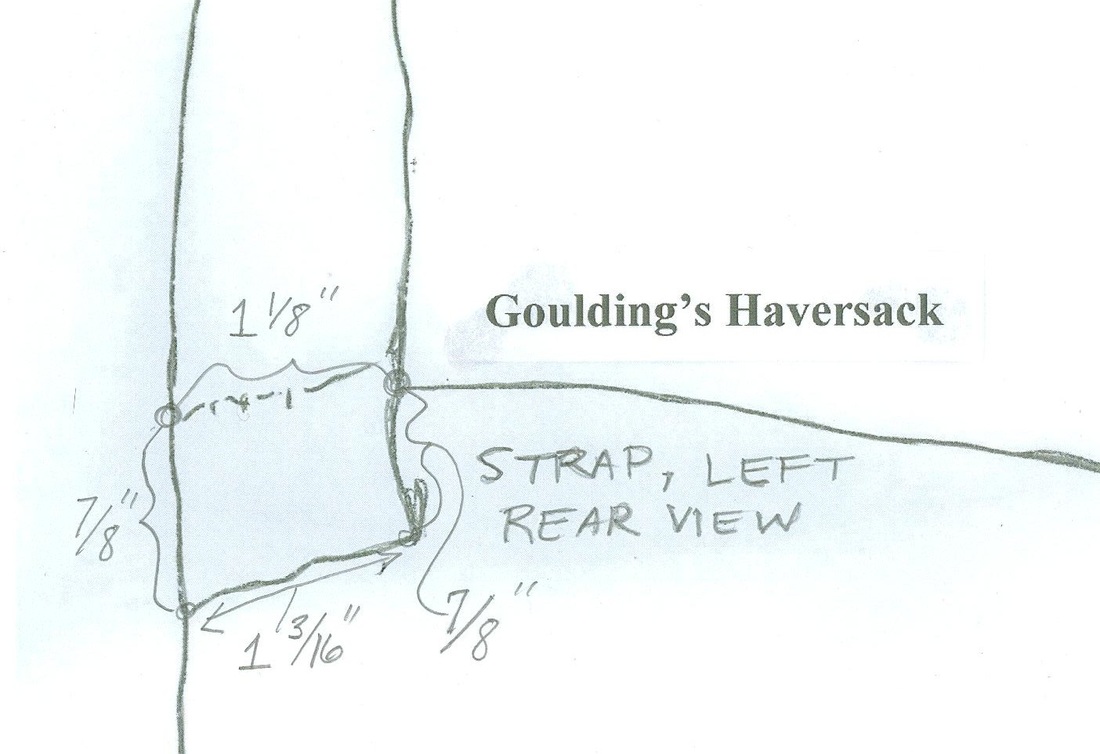

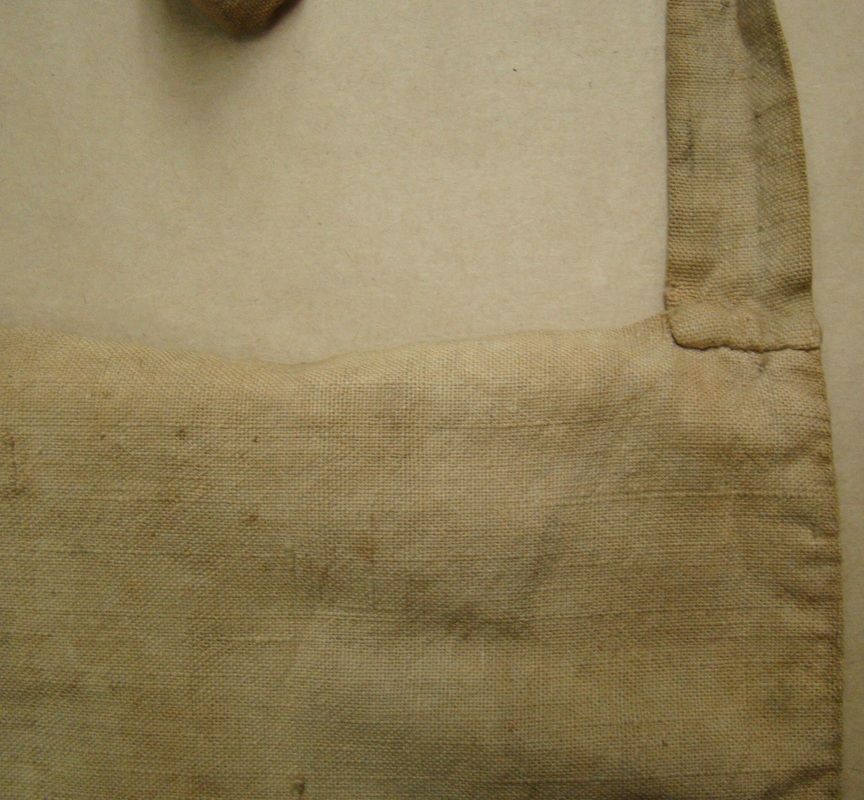

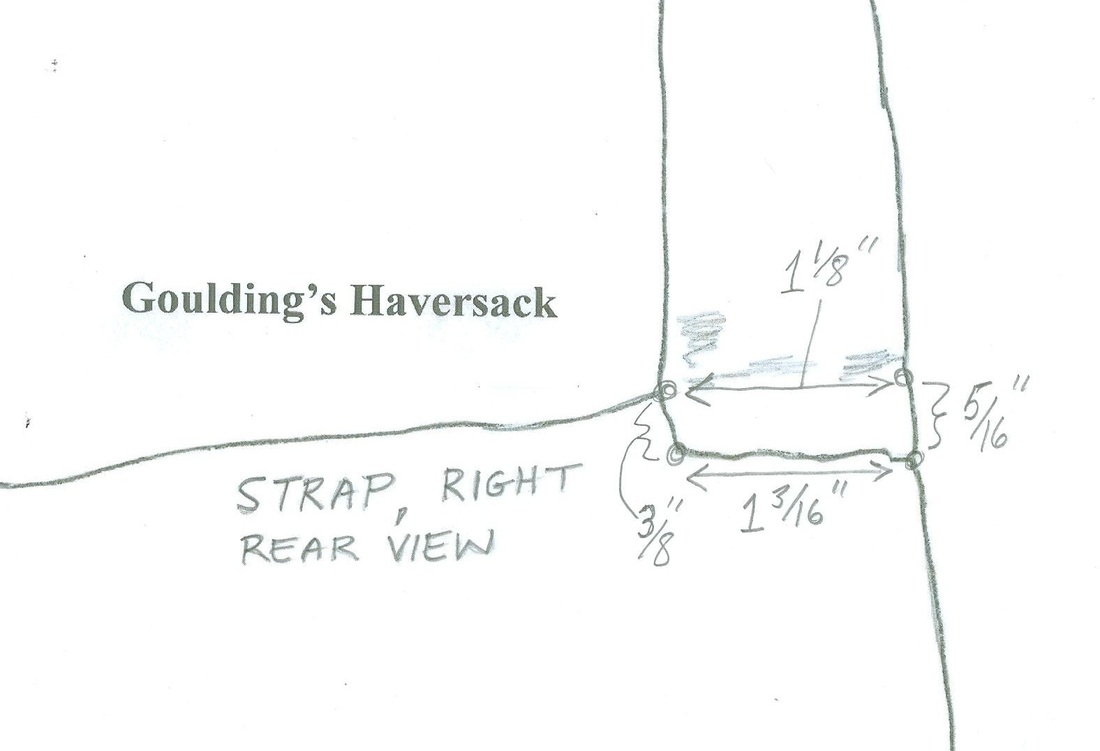

The Goulding haversack is made of a coarse, unbleached osnaburg. The satchel is not enameled, has no gussets, and the flap closes with a single bone button. Typical of Confederate haversacks, the satchel’s depth exceeds its width. There is a small, plaid “poke”sack sewn to the front opening of the satchel, and suspending it on the inside. The strap is made of the same material as the satchel, being folded over and sewn closed. This artifact embodies what most collectors consider the quintessential Confederate haversack. In fact, my own research indicates that about two-thirds of Confederate haversacks had enameled satchels (the straps were seldom enameled), and web straps. However, this does not distract at all from the artifact’s appeal as the following images show.

The quartermaster-made haversack comes from the Goulding family. At least two Goulding brothers served in the Army of Northern

Virginia. Both were from Darien, Georgia. Francis R. Goulding served with the Jeff Davis Legion, Mississippi Cavalry, and ended the war in a hospital in Charlotte, North Carolina. His brother, C.H. Goulding, served with the 8th Georgia Infantry. C.H. Goulding died in General Hospital 21, Richmond, Virginia, December 24, 1862 of “remittent fever” (caused by gonorrhea). The collection has a number of objects from the Goulding family, to include Francis’s vest fashioned from a Tait jacket. The vest has strong provenance to Francis, but the haversack’s story is murkier, since family legend attributes it to C.H. The connection with C.H. is tenuous, because it is unlikely that the hospital would have returned a haversack to the family in 1862, unless it contained other personal items. Even then, sending this home would have been an extravagance that stretches plausibility. It is more likely that the haversack belonged to Francis, and that he brought it home with his vest and other Confederate memorabilia. This makes sense to me, because the haversack is clean and in good

condition. It is likely that Francis got this fresh haversack while he was in the hospital in Charlotte, and the war ended before it saw any heavy field use. In any case, the haversack is an amazing example of a cheap, simple, mass-produced Confederate haversack, typical

of what Southern soldiers received from the quartermaster.

The Goulding haversack is made of a coarse, unbleached osnaburg. The satchel is not enameled, has no gussets, and the flap closes with a single bone button. Typical of Confederate haversacks, the satchel’s depth exceeds its width. There is a small, plaid “poke”sack sewn to the front opening of the satchel, and suspending it on the inside. The strap is made of the same material as the satchel, being folded over and sewn closed. This artifact embodies what most collectors consider the quintessential Confederate haversack. In fact, my own research indicates that about two-thirds of Confederate haversacks had enameled satchels (the straps were seldom enameled), and web straps. However, this does not distract at all from the artifact’s appeal as the following images show.

|

|

|

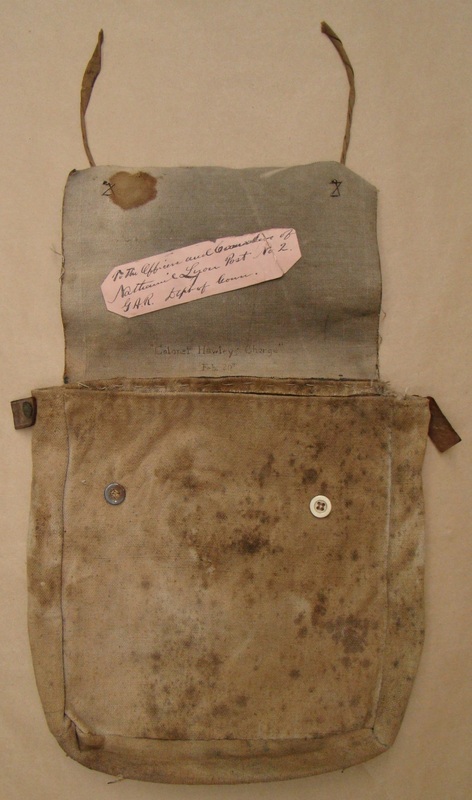

The

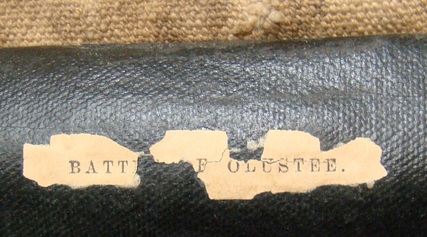

other haversack’s story is more fascinating than that of the first. This haversack was scavenged from the Olustee

battlefield by Federal soldiers in the wake of Colonel Hawley’s charge against

the Confederate line, February 20, 1864.

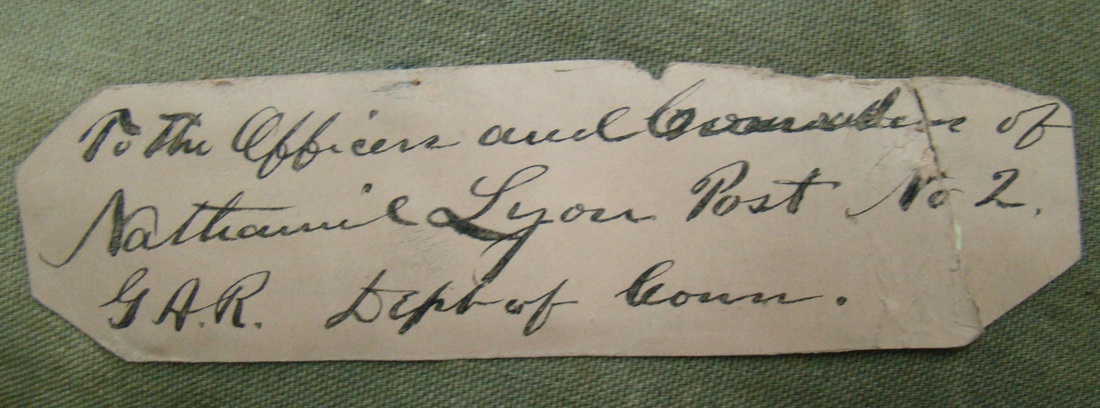

Donors, presumably Union veterans of the Battle of Olustee, gave it to

the Nathaniel Lyon G.A.R. Post No. 2, Department of Connecticut, after the war.

When the post closed, the membership

transferred title of the haversack to a private collector.

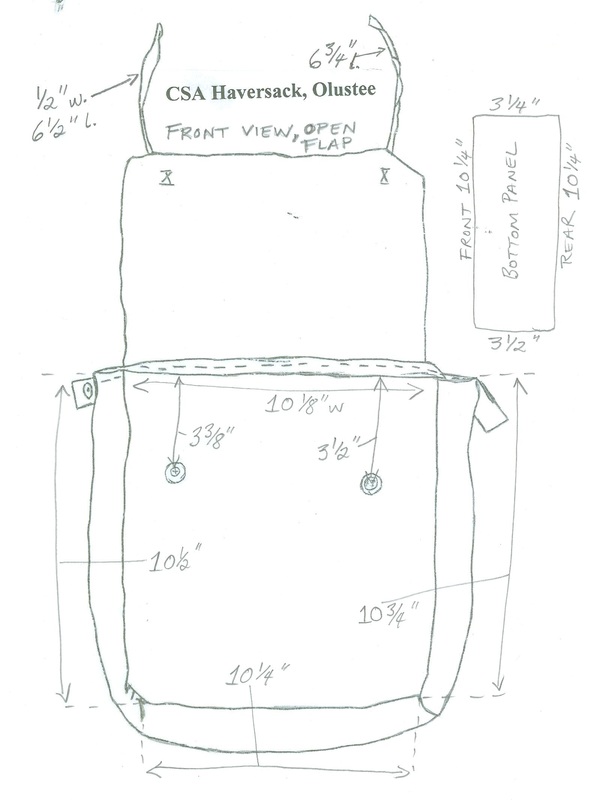

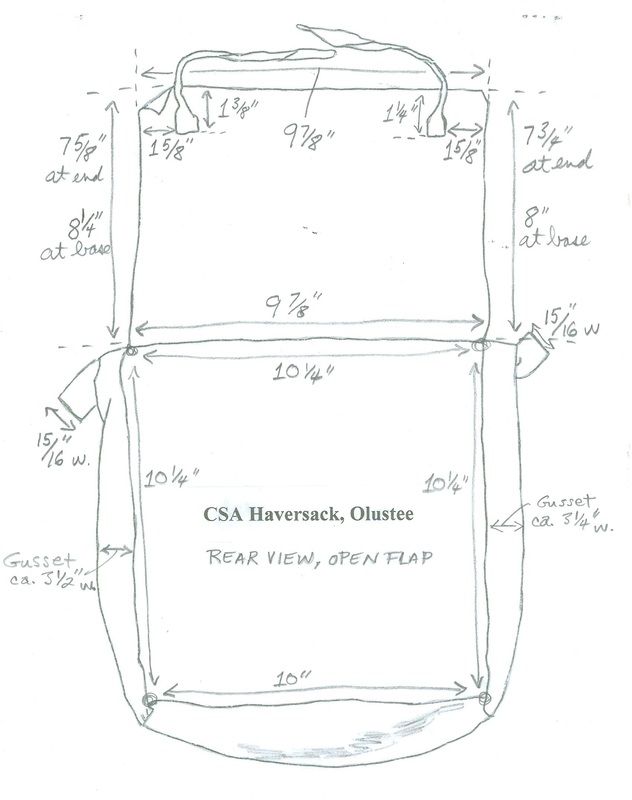

Aside from the excellent provenance, the artifact is an interesting example of a custom made haversack. The satchel is made from coarse, unbleached osnaburg. It consists of five pieces: front and rear panels; side gussets, and a bottom gusset. The flap is a separate piece of enameled cloth attached to the rear panel at the satchel’s opening. The strap, which survives as only two remnants, was originally a heavy-weight leather strap, 15/16” wide, that is riveted to the outside side gussets. All of the pieces are joined together with a widely-spaced basting stitch, and it is a wonder that held together so well. The fact that the loose stitching shows no signs of having burst open suggests that the haversack was not in use very long before it was taken as a battle-field souvenir. The stitching would have been unacceptable for a depot-made haversack because the satchels had to endure the stress of carrying a heavy load, and the basting stitch could not bear such stress for long.

Another feature worth noting is the manner for securing the flap. The flap itself has two cotton tie tapes secured near the bottom edge. The front panel has two buttons corresponding roughly to the placement of the tie tapes. The arrangement seems awkward, however, because tie tapes do not lend themselves to securing to buttons, and the buttons are set far too high to align with the tapes when the flap is closed. There is no ready explanation for this, but then, young soldiers fashioned numerous field modifications that were not entirely perfect.

Aside from the excellent provenance, the artifact is an interesting example of a custom made haversack. The satchel is made from coarse, unbleached osnaburg. It consists of five pieces: front and rear panels; side gussets, and a bottom gusset. The flap is a separate piece of enameled cloth attached to the rear panel at the satchel’s opening. The strap, which survives as only two remnants, was originally a heavy-weight leather strap, 15/16” wide, that is riveted to the outside side gussets. All of the pieces are joined together with a widely-spaced basting stitch, and it is a wonder that held together so well. The fact that the loose stitching shows no signs of having burst open suggests that the haversack was not in use very long before it was taken as a battle-field souvenir. The stitching would have been unacceptable for a depot-made haversack because the satchels had to endure the stress of carrying a heavy load, and the basting stitch could not bear such stress for long.

Another feature worth noting is the manner for securing the flap. The flap itself has two cotton tie tapes secured near the bottom edge. The front panel has two buttons corresponding roughly to the placement of the tie tapes. The arrangement seems awkward, however, because tie tapes do not lend themselves to securing to buttons, and the buttons are set far too high to align with the tapes when the flap is closed. There is no ready explanation for this, but then, young soldiers fashioned numerous field modifications that were not entirely perfect.

The author would like to thank Mr. Richard Ferry of the Florida Confederate Museum for his generosity in sharing these wonderful artifacts. As time permits, more of the Florida Confederate collection will be studied and shared on this website, as well. Readers are also reminded that the images herein are property of Adolphus Confederate Uniforms and may not be reproduced without the consent of the author.