The Quintessential Confederate Cap, Part II: Caps of the Richmond Clothing Bureau

Fred Adolphus, 9 June 2023

Updated 27 April 2025

Continued from Part I: click here to navigate back to the previous page...

Having touched upon the different variants of Confederate caps, we return to the quintessential Confederate chasseur cap. It now bears talking about this cap’s mass production through the Quartermaster Department. Each regional clothing bureau established its own manufacturing depots and contracts for clothing, and these different operations made their own subtly distinct caps. These differences allow us to identify them to specific depots. The largest and most significant of all the clothing operations was the Richmond Clothing Bureau, or Depot. Several of its quartermaster issue, enlisted caps survive in collections today.

The Richmond Depot is renowned for having made its uniforms according to fairly stringent pattern specifications. Its jackets are easily identifiable as such, and no less, its caps are distinguishable from those of other depots. Surviving originals provide information pertaining to its basic characteristics and dimensions. While subtle nuances might vary slightly from cap to cap, the general templated pattern is identical. General characteristics include the following.27

The chief basic cloth used in making the Richmond Depot caps was imported, blue-gray kersey, or satinet of the same color. In this study I use the contemporary terms for these imported fabrics: cadet gray and Confederate gray, and I use them interchangeably. The Confederate Quartermaster Department, and Southerners themselves used these terms for this color of cloth, so I am using the terms herein, rather than the less common, contemporary term of "English army cloth," which has found currency among modern reenactors.

The body consisted of a one-piece band, two side pieces and a crown piece, sewn in the chasseur style with a countersunk crown. Approximate measurements are: band 1 1/8 to 1 ¼ inches wide; sides in front above the band to the fold in the crown 1 5/8 to 1 ¾ inches high, sides in the rear above the band to the fold ca 5 inches high; diameter of crown inside the folds about 4 ½ inches, and diameter with folded edges about 5 3/8 inches.

Having touched upon the different variants of Confederate caps, we return to the quintessential Confederate chasseur cap. It now bears talking about this cap’s mass production through the Quartermaster Department. Each regional clothing bureau established its own manufacturing depots and contracts for clothing, and these different operations made their own subtly distinct caps. These differences allow us to identify them to specific depots. The largest and most significant of all the clothing operations was the Richmond Clothing Bureau, or Depot. Several of its quartermaster issue, enlisted caps survive in collections today.

The Richmond Depot is renowned for having made its uniforms according to fairly stringent pattern specifications. Its jackets are easily identifiable as such, and no less, its caps are distinguishable from those of other depots. Surviving originals provide information pertaining to its basic characteristics and dimensions. While subtle nuances might vary slightly from cap to cap, the general templated pattern is identical. General characteristics include the following.27

The chief basic cloth used in making the Richmond Depot caps was imported, blue-gray kersey, or satinet of the same color. In this study I use the contemporary terms for these imported fabrics: cadet gray and Confederate gray, and I use them interchangeably. The Confederate Quartermaster Department, and Southerners themselves used these terms for this color of cloth, so I am using the terms herein, rather than the less common, contemporary term of "English army cloth," which has found currency among modern reenactors.

The body consisted of a one-piece band, two side pieces and a crown piece, sewn in the chasseur style with a countersunk crown. Approximate measurements are: band 1 1/8 to 1 ¼ inches wide; sides in front above the band to the fold in the crown 1 5/8 to 1 ¾ inches high, sides in the rear above the band to the fold ca 5 inches high; diameter of crown inside the folds about 4 ½ inches, and diameter with folded edges about 5 3/8 inches.

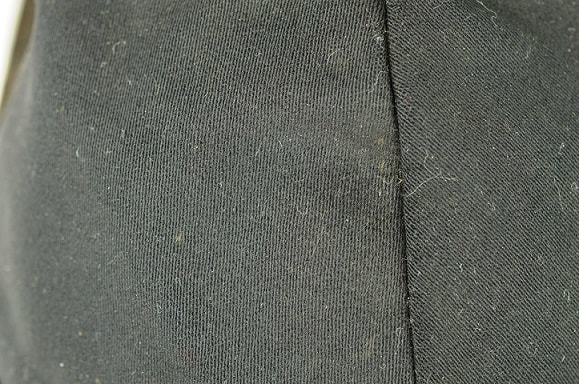

The visor was made of pasteboard covered with black enameled cloth. The outside edge of the visor has a welt, approximately one inch wide folded over the edge and machine-sewn in place. The visor is about 1/8 inch thick, and is whip-stitched to the front on the cap. The visor was usually finished with a shiny coating of varnish. The visor has a distinctive, templated pattern, measuring side to side, across the ends 6 3/8 to 6 5/8 inches long; side to side, across the middle 6 ½ to 6 13/16 inches long; front to rear from the front edge to the line between the ends 4 to 4 5/8 inches wide; and front to rear, in the center from the front edge to the seam line 1 7/8 to 2 inches wide. The visor end points are cut off, forming a flat edge about ¼ inch across.

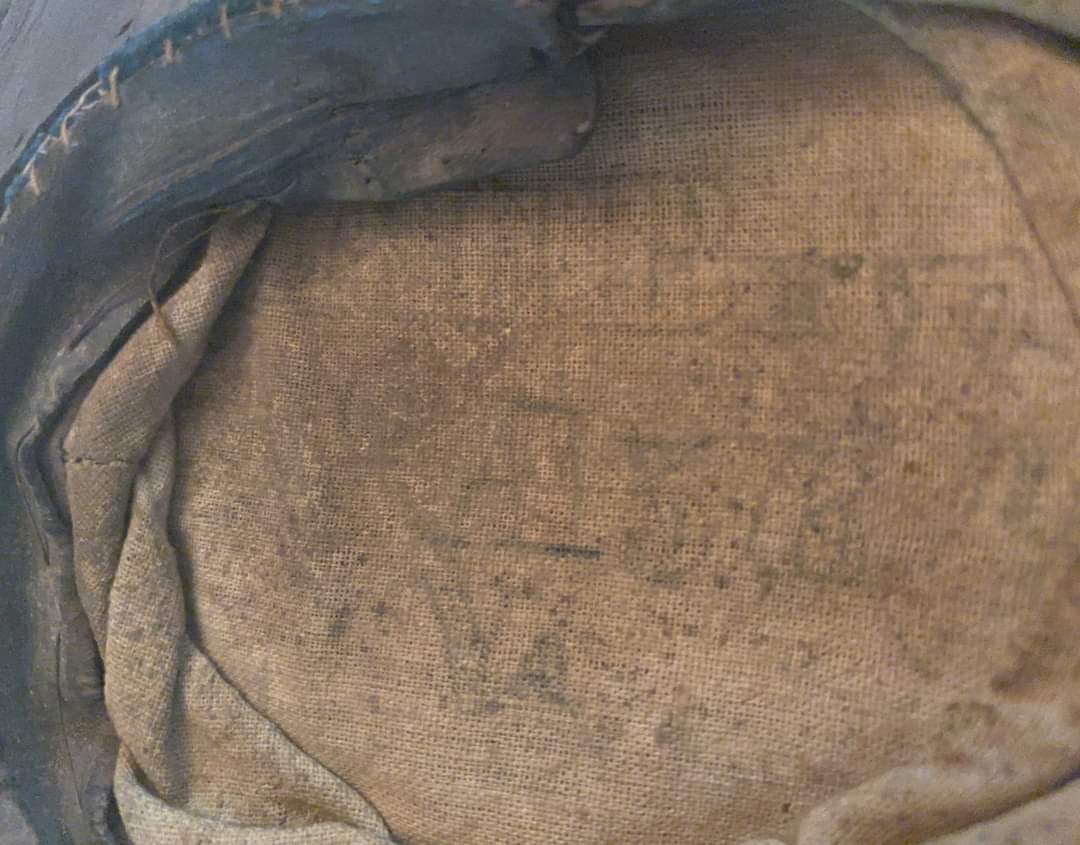

The lining was made of an unbleached white, osnaburg cotton, usually consisting of two side-pieces and a crown piece, that conformed roughly to the outside form of the cap; the sides sewn to the crown in the same countersunk manner as the body. To a lesser degree, a bag-style lining with a draw string closure at the top was employed (a pattern made from a single piece of cloth, with one seam, that did not conform to the outside cap pattern).

The sweatband was made of black enameled cloth (varnished); sewn to the base of the cap, turned and ironed down, then whip-stitched around the base and frequently whip-stitched to the lining on the sides; the finished measurement is 1 1/16 to 1 ¼ inches wide. In some cases, the bottom edge of the sweatband has an unfinished edge that is whip stitched to the base. The base of the cap, under the sweatband, had a buckram interlining. This stiffening was approximately the same width as the sweatband.

The sweatband was made of black enameled cloth (varnished); sewn to the base of the cap, turned and ironed down, then whip-stitched around the base and frequently whip-stitched to the lining on the sides; the finished measurement is 1 1/16 to 1 ¼ inches wide. In some cases, the bottom edge of the sweatband has an unfinished edge that is whip stitched to the base. The base of the cap, under the sweatband, had a buckram interlining. This stiffening was approximately the same width as the sweatband.

The chinstrap was made of black enameled cloth, also varnished, the same as the visor components. Most of the surviving Richmond caps are missing their chinstraps, but of the six that remain intact, four are adjustable, two-piece; one is a non-functional, one-piece type; and, the last is not visible in the available photo. The ends of the chinstraps are all cut off straight, where the buttons are attached, and all have unfinished, raw edges. The chinstraps are approximately 7/16 inches wide. The functional, two-piece chinstraps have keeper loops sewn in place, made of the same raw-cut enameled cloth, and of the same width as the straps. On these, the adjusting end has a small tab sticking out the side of the keeper for the soldier to pinch and pull. There was no “correct” side for the adjustment tab: it ended up on whatever side the seamstress happened to put it on when she was attaching the chinstrap to the cap. Of the four functional chinstraps, two adjust on the right side, and two on the left. The chinstrap buttons, when still intact, include a variety of types: japanned tin, white glass shirt buttons, white bone trouser buttons, Confederate “A” and “I” buttons, and state seal buttons.

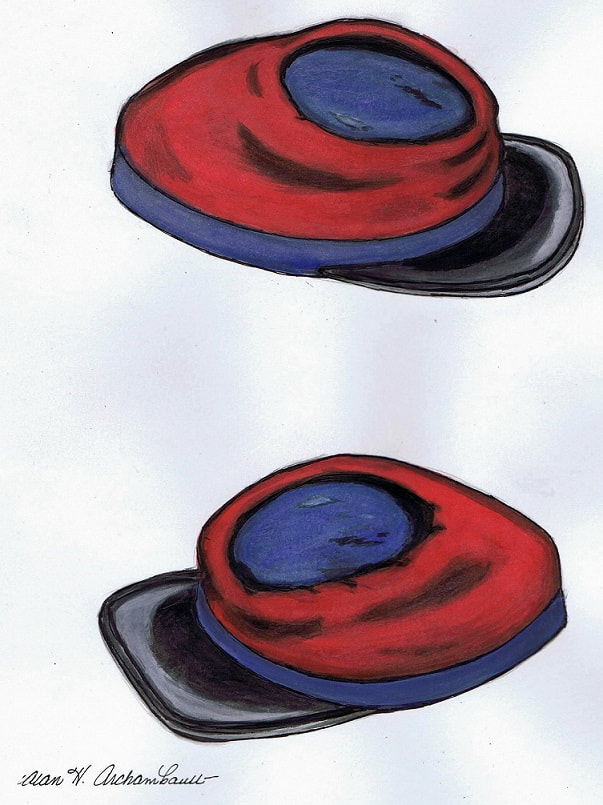

The Richmond caps were made in both the solid, basic cloth color, or in a “variegated” color scheme unique to the Richmond Depot. The plain, cadet gray caps (with the band, sides and crown all of the same color) might have served as a “universal issue” cap since they were devoid of a specific, branch-trim color. The variegated version was branch specific. The variegated color scheme had the cap’s band and crown of one color and the side pieces of a contrasting color. For instance, variegated artillery caps might have a red band and crown with cadet gray sides, or a cadet gray band and crown with red sides. The surviving, variegated enlisted caps incorporate the red artillery color. No enlisted caps remain with an infantry color scheme. However, one variegated officer cap with the infantry trim color of light blue has survived. At least two variegated officer artillery caps survive and two survive with black trim-color cloth. No variegated cavalry caps, that is Richmond caps trimmed with yellow cloth, remain at all.

Confederate staff officer, McHenry Howard, described artillerymens' caps as “variegated,” and it is from Howard’s account that I have adopted this contemporary term. Howard recalled how in the spring of 1865, a brigade of heavy artillery was armed with muskets, and re-organized as infantry, with about 1,400 men. “The heavy artillerymen having been stationary around Richmond had been able to keep their uniforms in better plight, and their scarlet caps and trimmings (artillery color) made them present a distinctive appearance to the army, of which they were now a regular part.” McHenry noted the brigade’s bravery and uniforms during the retreat from Richmond. “In fact, it is evident to me that the fresher and variegated caps and uniforms of the heavy artillerymen made the enemy suppose they belonged to the ‘Navy Brigade’ or battalion…”

Another observation, this made a Union officer in August 1864, may also refer to Richmond Depot, variegated caps. The officer remarked of 2nd Maryland Infantry prisoners, “Among them [the Confederate prisoners] were a number of their Maryland brigade, quite well dressed and superior men… They had the remains of fancy clothes on, including little kepis, half grey and half sky blue.”28

Remarkably, many officers copied this unique style when having tailors make their caps. This may indicate that the Richmond enlisted cap’s variegated color scheme was perceived as unique to the Army of Northern Virginia, and that the officer corps wanted their caps to reflect this style. Benjamin S. Pendleton’s artillery cap and Captain James Lyle Clarke’s infantry cap are two examples of variegated officer caps, complete with gold braid, that were worn in 1864-65. However, there is some evidence to suggest that early-war, officer’s caps may have inspired the Richmond Depot variegated pattern. Two such caps have provenance to 1861-62. One is an artillery cap with gold braid worn by Lieutenant Charles Ellis Munford who was killed at Malvern Hill. The other was worn by Captain Benjamin Chase, who likewise died in May 1862. Chase’s cap has no gold braid, and the band and crown were made from black velvet. The sides included dark gray, fine woolen cloth. Another variegated officer cap survives from the late-war period: that of First Lieutenant William H. Harwood, 3rd Virginia Cavalry. Harwood’s cap offers further documentation for the officer’s preference for the variegated color scheme.

Surviving, original Richmond caps have provenance to the last year of the war. This late provenance is reflected in the imported fabrics they are made from: cadet gray kersey and satinet, red satinet, fine scarlet woolen, and Confederate, light blue kersey. The heavy use of cadet gray and light blue kerseys for the manufacture of jackets and trousers probably yielded ample quantities of scrap cloth with which to make caps. This might account for the significant number of plain, cadet gray caps that survive today. Prior to the arrival of the aforementioned fabrics, the Richmond Depot would have made caps of coarse, Southern-made fabrics, such as cassimere and jeans, or of kersey from the Crenshaw Woolen Mill in Richmond. Crenshaw woolens came in both fine and coarse grades. The “Crenshaw’s gray” woolen which sold for $28.00 per yard was a superior, officer grade article. Crenshaw’s “coarse jeans,” at $4.00 a yard, was intended for enlisted clothing.29 The Crenshaw Mill dyed its own woolens and produced “light blue and grey cloths” for Confederate uniforms.30 Since no Richmond caps survive from the first two years of the war, one has to rely on written records and contemporary images to ascertain what the caps were made from. Surviving uniforms from the period that appear to have been made from Crenshaw’s gray cloth indicate that it was a blue gray hue, much lighter than the imported cadet gray. Crenshaw may also have made light blue, dark blue, black and red trim cloths. The limited records indicate that the early Richmond caps were made from gray and blue “casimere” and “military cloth,” perhaps from the Crenshaw Woolen Mill. The mill was destroyed by a fire on May 15, 1863, thereby ending its production for the Confederacy.

Ironically, available manufacturing records for Richmond caps date from the first two years of the war, May 1861 to June 1863, precisely the period from which no depot caps survive. These include invoices from ten cap and cap component manufacturers, of whom the largest producers were Frank Binford, and Charles and Mary McIndoe. Total purchases by the Richmond quartermaster during this period included 87,834 caps, and payment for perforating 13,341 visors (along the interior edge of the visor for attachment to the cap). Descriptions of the caps in the invoices are minimal, but include the following for 1861: “Grey Caps,” “Blue Caps,” “Cadet Caps,” “Grey Fatigue Caps,” “Blue Fatigue Caps,” “Fatigue Caps,” and “Gen’l Johnson Camp Caps.” In 1862, caps were described as “Grey Caps,” “Blue Caps,” “Grey Fatigue Caps,” “Forage Caps,” “Cap Covers,” and “Gen’l Johnson Camp Caps.” In 1863, invoices carried, “Grey Caps,” “Light Grey Caps,” “Grey Cadet Caps,” “Military Caps,” and “Beaverteen Caps.” The beaverteen caps were made from a heavy twilled cotton fabric that had an uncut pile and a short nap.31

Further information from the 1863 invoices confirms the use of cassimere to make caps, along with oil cloth, bone buttons, spool cotton thread, binder boards, military cloth, cap fronts, and sheep skins. The oil cloth and sheep skins would have been used for sweatbands, and the binders board (pasteboard) for cap crown and band stiffening. Frank Binford’s records indicate that the government routinely supplied him with the buttons that he used to for his caps.32 The cap fronts, or visors, were manufactured as separate component that was also furnished to cap makers by the quartermaster. The cap fronts were made of pasteboard, covered with oil cloth top and bottom, with a machine-stitched, oil cloth welt around the exterior edge of the visor.33

Conjecturally, the gray and blue fabrics used from 1861 to 1863 were domestic products, possibly even Crenshaw mill woolens. The cassimere fabrics were not from the Crenshaw mill, but were products of at least two weavers: Benbow and Yadkins. In any case, the invoices largely pre-date the arrival and usage of imported cadet gray and light blue cloth in Virginia.34 Furthermore, purchases of at least 88,000 caps by the Richmond quartermaster in two years would have supplied roughly half of the Army of Northern Virginia with caps (allowing for an issue of one cap each year per soldier).

At least fifteen, Richmond Depot, enlisted, government-issue caps have survived to present day, by far the largest number of caps from any single depot. While the Richmond cap may not have been the first choice of headgear in Lee’s army, the surviving caps indicate that significant numbers were issued to “Virginia Army” troops. Quartermaster records likewise indicate that the Richmond Depot manufactured and issued significant quantities of caps to the Army of Northern Virginia. For instance, during the 3rd and 4th quarters of 1864 and up to 21 January 1865, the quartermaster made field issues to the Army of Northern Virginia amounting to 27,011 hats and caps.35 Judging from the proportions of surviving originals, and corresponding images, it seems that artillerymen were especially fond of wearing caps. In fact, all of the surviving Richmond enlisted caps with colored trim are artillery caps (having red colored trim in variegated configuration). Given that there were many more infantrymen than artillerymen, yet half the surviving Richmond enlisted caps are artillery, it is reasonable to assume that a much higher percentage of artillerymen wore caps than infantry. Contemporary images of Confederate prisoners and other substantiating data suggests that Lee’s infantrymen wore caps to a far lesser degree than artillerymen, but they wore them nonetheless. Interestingly, at least two of the surviving caps were worn by cavalrymen.

There are nine fully-authenticated, solid, cadet gray Richmond caps: i.e. the crown, side and band pieces all made from the same color of cloth. Three of these caps have provenance. The general construction and the enameled visors are the same for all of these identified as Richmond caps. With the exception of the Rowan satinet cap, all are made of coarse, cadet gray kersey. The linings are all unbleached osnaburg, although two linings are cut in the “adjustable bag” style.

The first of these plain, cadet gray caps resides in the Michael Kramer collection. It retains its two-piece chinstrap that is secured with two, natural white bone, four-hole trouser buttons. The sweatband is missing, which has left the lining loose, enabling one to lift the side and look at the interior construction of the cap. The cap is made with quarter-inch seams and sewn together with black thread. The lining is cut in the bag style with its pull cord to adjust at the top. The bag lining has only one seam at rear. The inside of the crown is covered with a layer of osnaburg that is whipstitched around the edge. A portion of this cover has been removed, perhaps due to damage, but the remainder retains a penciled name, rather faded and indistinct. Other than the penciled name, the cap is without provenance.

Confederate staff officer, McHenry Howard, described artillerymens' caps as “variegated,” and it is from Howard’s account that I have adopted this contemporary term. Howard recalled how in the spring of 1865, a brigade of heavy artillery was armed with muskets, and re-organized as infantry, with about 1,400 men. “The heavy artillerymen having been stationary around Richmond had been able to keep their uniforms in better plight, and their scarlet caps and trimmings (artillery color) made them present a distinctive appearance to the army, of which they were now a regular part.” McHenry noted the brigade’s bravery and uniforms during the retreat from Richmond. “In fact, it is evident to me that the fresher and variegated caps and uniforms of the heavy artillerymen made the enemy suppose they belonged to the ‘Navy Brigade’ or battalion…”

Another observation, this made a Union officer in August 1864, may also refer to Richmond Depot, variegated caps. The officer remarked of 2nd Maryland Infantry prisoners, “Among them [the Confederate prisoners] were a number of their Maryland brigade, quite well dressed and superior men… They had the remains of fancy clothes on, including little kepis, half grey and half sky blue.”28

Remarkably, many officers copied this unique style when having tailors make their caps. This may indicate that the Richmond enlisted cap’s variegated color scheme was perceived as unique to the Army of Northern Virginia, and that the officer corps wanted their caps to reflect this style. Benjamin S. Pendleton’s artillery cap and Captain James Lyle Clarke’s infantry cap are two examples of variegated officer caps, complete with gold braid, that were worn in 1864-65. However, there is some evidence to suggest that early-war, officer’s caps may have inspired the Richmond Depot variegated pattern. Two such caps have provenance to 1861-62. One is an artillery cap with gold braid worn by Lieutenant Charles Ellis Munford who was killed at Malvern Hill. The other was worn by Captain Benjamin Chase, who likewise died in May 1862. Chase’s cap has no gold braid, and the band and crown were made from black velvet. The sides included dark gray, fine woolen cloth. Another variegated officer cap survives from the late-war period: that of First Lieutenant William H. Harwood, 3rd Virginia Cavalry. Harwood’s cap offers further documentation for the officer’s preference for the variegated color scheme.

Surviving, original Richmond caps have provenance to the last year of the war. This late provenance is reflected in the imported fabrics they are made from: cadet gray kersey and satinet, red satinet, fine scarlet woolen, and Confederate, light blue kersey. The heavy use of cadet gray and light blue kerseys for the manufacture of jackets and trousers probably yielded ample quantities of scrap cloth with which to make caps. This might account for the significant number of plain, cadet gray caps that survive today. Prior to the arrival of the aforementioned fabrics, the Richmond Depot would have made caps of coarse, Southern-made fabrics, such as cassimere and jeans, or of kersey from the Crenshaw Woolen Mill in Richmond. Crenshaw woolens came in both fine and coarse grades. The “Crenshaw’s gray” woolen which sold for $28.00 per yard was a superior, officer grade article. Crenshaw’s “coarse jeans,” at $4.00 a yard, was intended for enlisted clothing.29 The Crenshaw Mill dyed its own woolens and produced “light blue and grey cloths” for Confederate uniforms.30 Since no Richmond caps survive from the first two years of the war, one has to rely on written records and contemporary images to ascertain what the caps were made from. Surviving uniforms from the period that appear to have been made from Crenshaw’s gray cloth indicate that it was a blue gray hue, much lighter than the imported cadet gray. Crenshaw may also have made light blue, dark blue, black and red trim cloths. The limited records indicate that the early Richmond caps were made from gray and blue “casimere” and “military cloth,” perhaps from the Crenshaw Woolen Mill. The mill was destroyed by a fire on May 15, 1863, thereby ending its production for the Confederacy.

Ironically, available manufacturing records for Richmond caps date from the first two years of the war, May 1861 to June 1863, precisely the period from which no depot caps survive. These include invoices from ten cap and cap component manufacturers, of whom the largest producers were Frank Binford, and Charles and Mary McIndoe. Total purchases by the Richmond quartermaster during this period included 87,834 caps, and payment for perforating 13,341 visors (along the interior edge of the visor for attachment to the cap). Descriptions of the caps in the invoices are minimal, but include the following for 1861: “Grey Caps,” “Blue Caps,” “Cadet Caps,” “Grey Fatigue Caps,” “Blue Fatigue Caps,” “Fatigue Caps,” and “Gen’l Johnson Camp Caps.” In 1862, caps were described as “Grey Caps,” “Blue Caps,” “Grey Fatigue Caps,” “Forage Caps,” “Cap Covers,” and “Gen’l Johnson Camp Caps.” In 1863, invoices carried, “Grey Caps,” “Light Grey Caps,” “Grey Cadet Caps,” “Military Caps,” and “Beaverteen Caps.” The beaverteen caps were made from a heavy twilled cotton fabric that had an uncut pile and a short nap.31

Further information from the 1863 invoices confirms the use of cassimere to make caps, along with oil cloth, bone buttons, spool cotton thread, binder boards, military cloth, cap fronts, and sheep skins. The oil cloth and sheep skins would have been used for sweatbands, and the binders board (pasteboard) for cap crown and band stiffening. Frank Binford’s records indicate that the government routinely supplied him with the buttons that he used to for his caps.32 The cap fronts, or visors, were manufactured as separate component that was also furnished to cap makers by the quartermaster. The cap fronts were made of pasteboard, covered with oil cloth top and bottom, with a machine-stitched, oil cloth welt around the exterior edge of the visor.33

Conjecturally, the gray and blue fabrics used from 1861 to 1863 were domestic products, possibly even Crenshaw mill woolens. The cassimere fabrics were not from the Crenshaw mill, but were products of at least two weavers: Benbow and Yadkins. In any case, the invoices largely pre-date the arrival and usage of imported cadet gray and light blue cloth in Virginia.34 Furthermore, purchases of at least 88,000 caps by the Richmond quartermaster in two years would have supplied roughly half of the Army of Northern Virginia with caps (allowing for an issue of one cap each year per soldier).

At least fifteen, Richmond Depot, enlisted, government-issue caps have survived to present day, by far the largest number of caps from any single depot. While the Richmond cap may not have been the first choice of headgear in Lee’s army, the surviving caps indicate that significant numbers were issued to “Virginia Army” troops. Quartermaster records likewise indicate that the Richmond Depot manufactured and issued significant quantities of caps to the Army of Northern Virginia. For instance, during the 3rd and 4th quarters of 1864 and up to 21 January 1865, the quartermaster made field issues to the Army of Northern Virginia amounting to 27,011 hats and caps.35 Judging from the proportions of surviving originals, and corresponding images, it seems that artillerymen were especially fond of wearing caps. In fact, all of the surviving Richmond enlisted caps with colored trim are artillery caps (having red colored trim in variegated configuration). Given that there were many more infantrymen than artillerymen, yet half the surviving Richmond enlisted caps are artillery, it is reasonable to assume that a much higher percentage of artillerymen wore caps than infantry. Contemporary images of Confederate prisoners and other substantiating data suggests that Lee’s infantrymen wore caps to a far lesser degree than artillerymen, but they wore them nonetheless. Interestingly, at least two of the surviving caps were worn by cavalrymen.

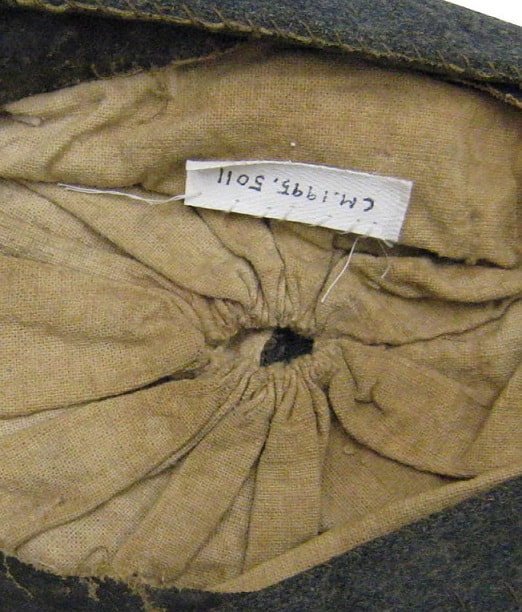

There are nine fully-authenticated, solid, cadet gray Richmond caps: i.e. the crown, side and band pieces all made from the same color of cloth. Three of these caps have provenance. The general construction and the enameled visors are the same for all of these identified as Richmond caps. With the exception of the Rowan satinet cap, all are made of coarse, cadet gray kersey. The linings are all unbleached osnaburg, although two linings are cut in the “adjustable bag” style.

The first of these plain, cadet gray caps resides in the Michael Kramer collection. It retains its two-piece chinstrap that is secured with two, natural white bone, four-hole trouser buttons. The sweatband is missing, which has left the lining loose, enabling one to lift the side and look at the interior construction of the cap. The cap is made with quarter-inch seams and sewn together with black thread. The lining is cut in the bag style with its pull cord to adjust at the top. The bag lining has only one seam at rear. The inside of the crown is covered with a layer of osnaburg that is whipstitched around the edge. A portion of this cover has been removed, perhaps due to damage, but the remainder retains a penciled name, rather faded and indistinct. Other than the penciled name, the cap is without provenance.

The second cap likewise has an adjustable bag lining. The cap retains its enameled sweatband, with the bottom edge folded inwards and whipstitched in place. The top edge is not stitched to the lining. The cap’s chinstrap and buttons are missing. The cap has no provenance.36

Two caps from the Gary Hendershott collection have the more common “conforming pattern” linings. The first of these has retained its two-piece chinstrap that is secured with Roman “I” buttons (Tice CSI203Am). The enameled sweatband’s bottom edge is folded inwards and whipstitched in place, while the top edge is basted to the lining.37 Hendershott’s other cap is missing its chinstrap and buttons. Its sweatband is secured to the base the same as the aforementioned Hendershott cap, but the top edge has been left unattached. Neither of these caps have provenance.

The next cap was worn by Captain Robert C. Rowan, Company D, 62nd Tennessee Infantry. Rowan’s regiment participated in the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, and was supplied by the Richmond Depot. Despite the fact that Rowan was an officer, he wore an enlisted depot cap, as did many officers. In contrast to the solid, cadet gray caps thus far discussed, its basic cloth is satinet. The chinstrap and buttons are missing, but the sweatband is intact. The sweatband appears to have an unfinished bottom edge, whip stitched in place, but left unattached at the top edge. The osnaburg lining is cut in the conforming pattern.38

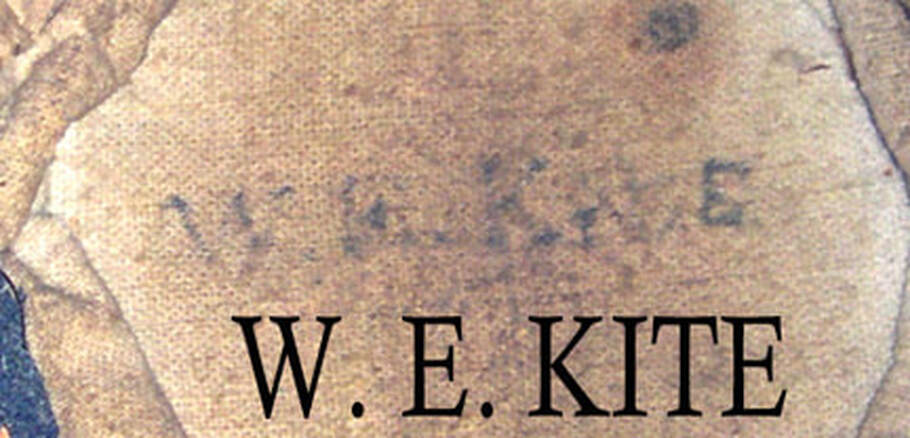

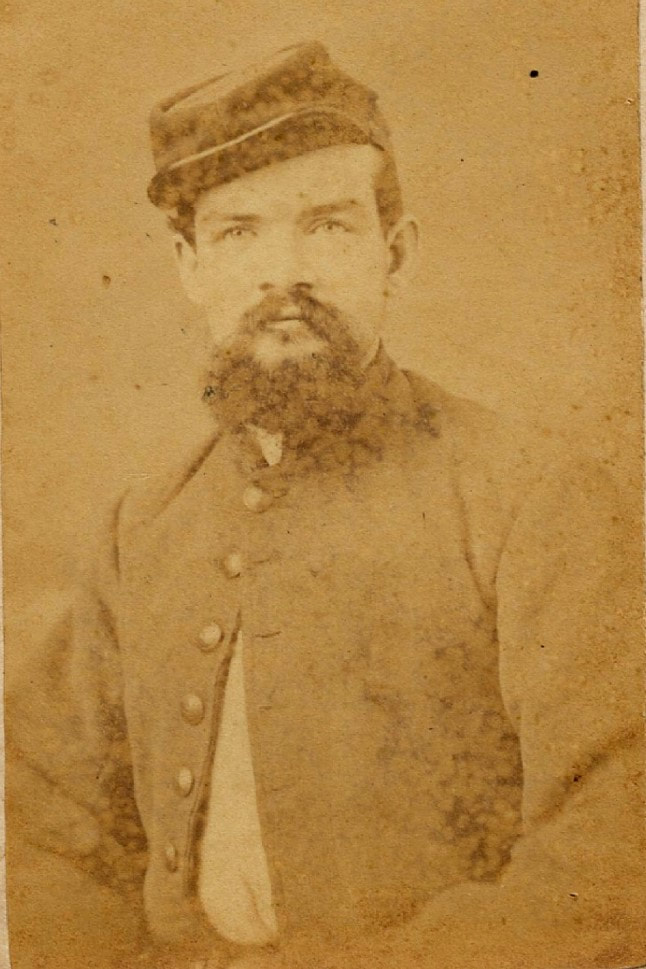

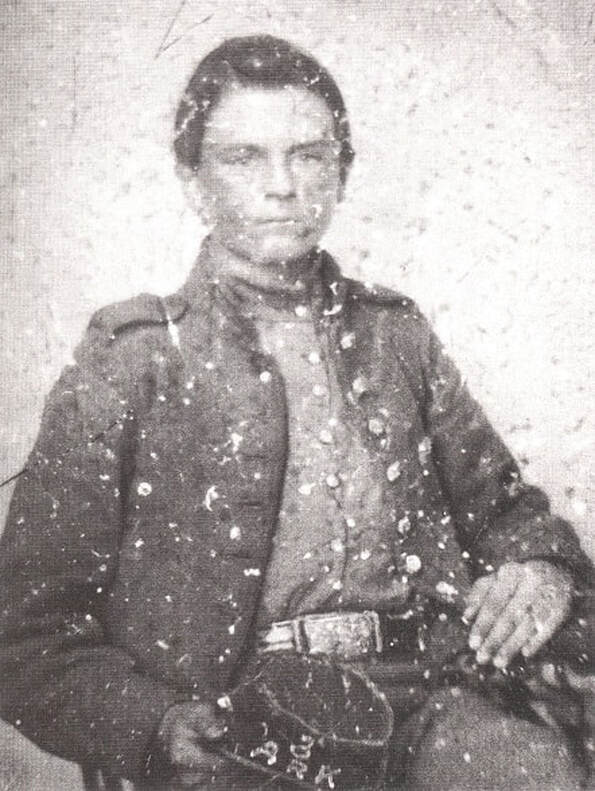

Two more general service caps survive with provenance, as well. Remarkably, both were worn by cavalrymen. The first of these “cavalry” caps was worn by First Sergeant William Edward Kite, Company A, 3rd Battalion Virginia Mounted Reserves. The company was mustered into service on 3 April 1864, and was also called Chrisman’s Boy Company for its leader, Captain George Chrisman. It served in Virginia through to the war’s end, although many of its members transferred to regular army commands upon turning eighteen. The company participated in battles in the Valley and served in the Richmond vicinity. Kite is thought to have been assigned to the company throughout its service. He probably got his cap at the same time that he got his Richmond Type 3 jacket with Roman “A” buttons, presumably late in the war. Both the cap and jacket are made of Confederate gray kersey.

The cap follows to usual tailoring of Richmond caps with a conforming, unbleached osnaburg lining. The basic cloth is coarse grade, imported blue-gray kersey. The dilapidated condition allows for a view of the interior components, including the pasteboard crown. Additionally, the cap has some unusual interior components: buckram interlining all the way up the sides; a pasteboard band stiffener; and, an unbleached osnaburg sweatband, that matches the lining. Kite also wrote his name on the inside crown lining.

The visor is the usual pasteboard covered with enameled cloth with an enameled welt machine-stitched around the outer edge. However, the chinstrap is leather with a japanned iron, adjustment buckle, a feature seen on no other Richmond cap. The chinstrap is secured with white glass, shirt buttons. Another unusual feature includes a third glass button attached to the rear of the cap band, presumably to secure a rain cover.39

The cap follows to usual tailoring of Richmond caps with a conforming, unbleached osnaburg lining. The basic cloth is coarse grade, imported blue-gray kersey. The dilapidated condition allows for a view of the interior components, including the pasteboard crown. Additionally, the cap has some unusual interior components: buckram interlining all the way up the sides; a pasteboard band stiffener; and, an unbleached osnaburg sweatband, that matches the lining. Kite also wrote his name on the inside crown lining.

The visor is the usual pasteboard covered with enameled cloth with an enameled welt machine-stitched around the outer edge. However, the chinstrap is leather with a japanned iron, adjustment buckle, a feature seen on no other Richmond cap. The chinstrap is secured with white glass, shirt buttons. Another unusual feature includes a third glass button attached to the rear of the cap band, presumably to secure a rain cover.39

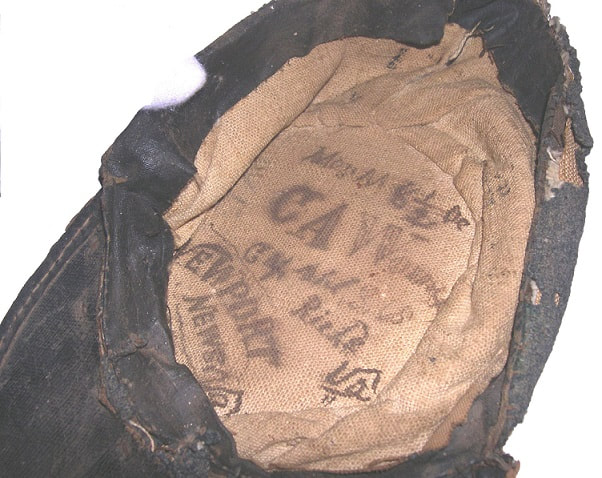

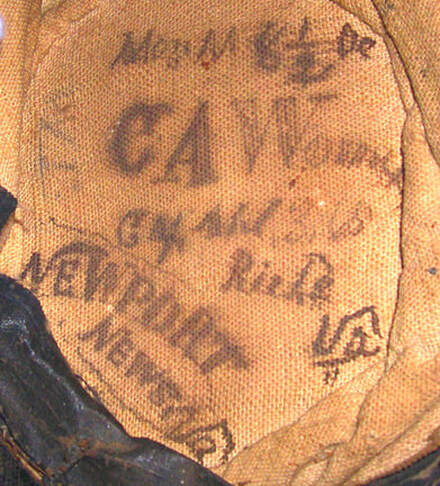

The second of the two cavalryman caps was worn by Charles Alexander Womack, Company E, 6th Virginia Cavalry. Womack served with the regiment from November 1863 until he was captured on 3 April 1865. He presumably received his cap late in the war.

Womack’s cap closely mirrors Kite’s cap. The chief differences are that Womack’s cap has the usual enameled cloth sweatband and lacks the buckram interlining that extends all the way up the sides. In fact, the cap may even lack buckram interlining in the band, although this is difficult to ascertain in the images. The chinstrap and buttons are missing. Womack was captured while a patient in the Confederate General Hospital in Richmond, Virginia. He penned his name, the time, date and place of his capture, as well as the city where he was transferred to (Newport News), on the inside of the crown lining.40

Womack’s cap closely mirrors Kite’s cap. The chief differences are that Womack’s cap has the usual enameled cloth sweatband and lacks the buckram interlining that extends all the way up the sides. In fact, the cap may even lack buckram interlining in the band, although this is difficult to ascertain in the images. The chinstrap and buttons are missing. Womack was captured while a patient in the Confederate General Hospital in Richmond, Virginia. He penned his name, the time, date and place of his capture, as well as the city where he was transferred to (Newport News), on the inside of the crown lining.40

Another Richmond Depot look-alike resides in the American Civil War Museum collection. This is a tailor-made copy of the Richmond cap with some notable quirks. The basic cloth is coarse, cadet gray kersey. The cap body is made from a single “side” piece with the seam in the front. The band piece also has its seam in the front. Such tailoring is a mystery for two reasons. It requires a very uneconomical cut in the cloth. It also makes the cap ill-fitting since it eliminates the curvature found in the rear seam that conforms to the shape of the head. In any case, the cap also has raw-cotton padded, polished white cotton fabric, machine-stitched quilting, a comfortable extravagance that mass-produced caps never had. The sweatband is dark russet-colored leather, which is another high-quality feature not afforded Richmond quartermaster caps. The band is reinforced with a pasteboard liner. The chinstrap, buttons and visor are missing. First Sergeant Richard Edward Wright, Company F, 55th Virginia Infantry, wore this deluxe cap in 1864.

A look-alike Richmond cap, made in the enlisted, chasseur pattern, was worn by 2nd Lieutenant William B. Wise. Wise was assigned to Company A, 46th Virginia Infantry and served as a doctor. The cap has a black, wool broadcloth band (two-piece). The sides and crown are made of black satinet. The visor is unbound, glazed leather and the leather chinstrap has an adjusting buckle and is secured with Virginia buttons. The inside is lined with light brown silk and the sweatband is russet leather. Perhaps the basic black color reflects affiliation with the medical corps. Wise’s simple cap is indicative of an officer cap made without braid, but of high-quality materials, that otherwise looks like an enlisted cap.

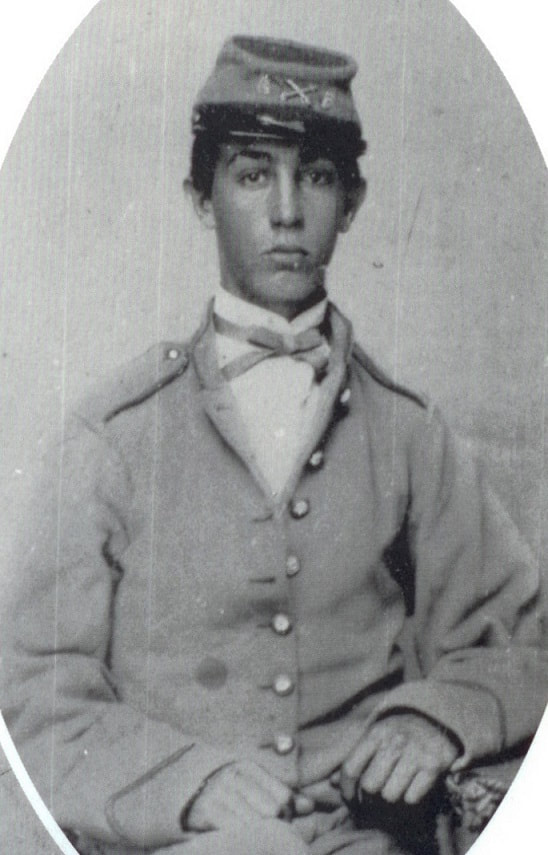

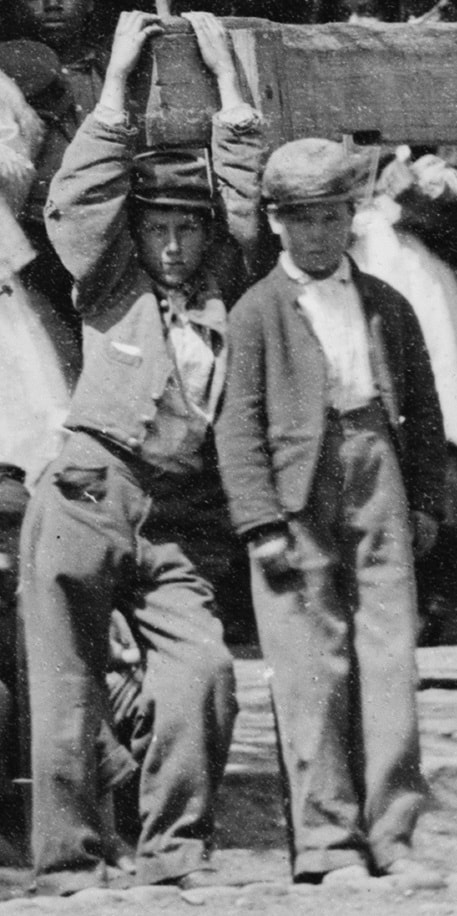

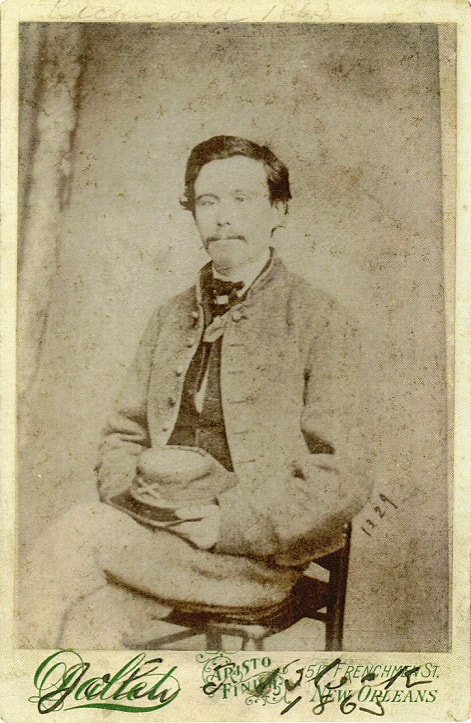

044: Richard Jesse Bailey, Company H, 3rd Arkansas Infantry holds a Richmond cap in his hand. The photographer has written “3 ARK” on its front. This mirror image picture has not been horizontally flipped so that the markings show legibly. Image courtesy of the Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas (see also, Military Images, and Portraits of Conflict Arkansas p. 29).

Regarding the variegated caps, two enlisted artillery caps survive with a “red, cadet gray, red” color scheme, (that is, having a red band and crown with cadet gray sides). Remarkably, both caps belonged to the same soldier: Private Robert William Royall, 1st Company, Richmond Howitzers. Royall served in this battery from 1861 until his surrender in Burkville, Virginia, April 24, 1865. Both caps are nearly identical, with red satinet crown and band cloth, and dark cadet gray, satinet sides. Both caps are lined with unbleached osnaburg (conforming pattern), and retain their enameled cloth sweatbands. The visors are both the usual pasteboard, covered with enameled cloth, with a machine-stitched welt around the outer edge. The cap that resided with Gary Hendershott is more complete, in that it retains its chinstrap and lined Roman “I” buttons, Richmond-made, extra rich, (Tice CSI203Am). The one-piece chinstrap is an anomaly for Richmond caps, and indicates that by the end of the war, the Richmond Depot was simplifying its cap production. The cap in the American Civil War Museum collection is missing its chinstrap and buttons. Its buckram stiffener, however, is visible through the damaged areas of the cap.41

046a: Robert William Royall's second cap, from the Henershott collection, is more intact than the first. The moth damage is not as bad, and the chinstrap and buttons are intact. Interestingly, the chinstrap is a non-functioning, one-piece model, something uncommon for Richmond caps. Furthermore, the cap has Roman infantry "I" buttons rather than artillery buttons. Hendershott. Artifact and image courtesy of Gary Hendershott Museum Consultants, Little Rock, Arkansas.

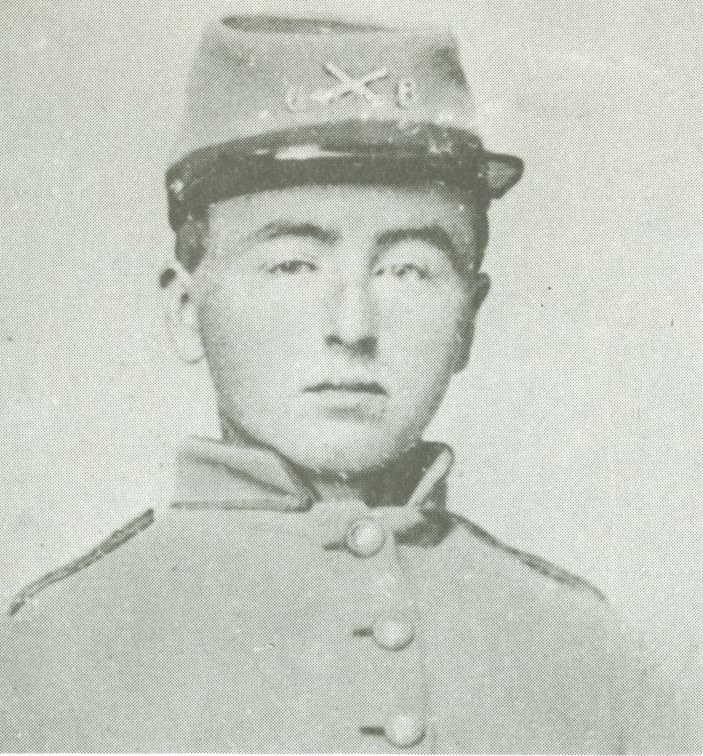

Several contemporary images document this variant of the Richmond artillery cap. There are two images of soldiers of Crenshaw’s Virginia Artillery Battery wearing this type of cap. One of the men is identified as Jonathon O. Farrell. Farrell’s original image is tinted red, in the trim color, and his image is dated three days after St. Patrick’s Day, in Richmond, Virginia, 1862. Both of the caps have identical brass badges: “C B” with crossed cannon barrels between the letters. The darker shaded, red crown and band parts are easy to distinguish. The sides are interpreted as gray components. Based upon the date of the image, and the early style Richmond jackets, it would appear that the Richmond Depot made the variegated pattern cap from the start.42

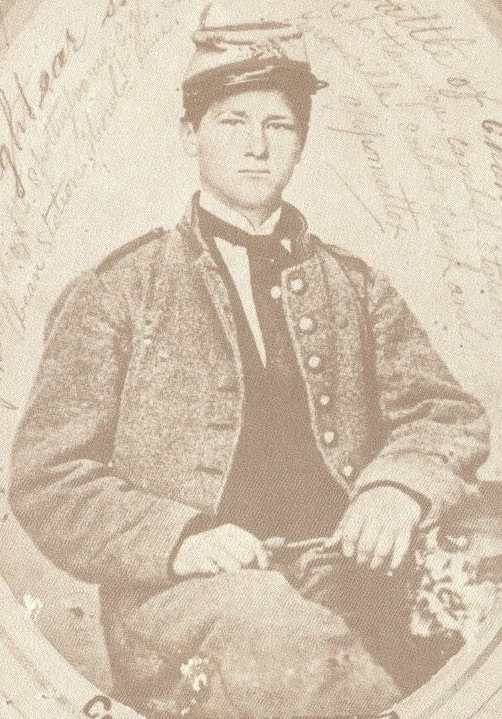

A picture of Corporal Theodore C. “Doc” Howard, of Parker’s Virginia Battery, shows him wearing a “red, gray, red” Richmond cap, to judge from the black and white photograph. Howard’s cap has the same type of crossed cannon insignia on the front that the Crenshaw caps have. The jacket and trouser match in color and coarse texture, but they contrast with the cap’s side-piece cloth, which is of a finer texture and lighter color.43

A picture of Corporal Theodore C. “Doc” Howard, of Parker’s Virginia Battery, shows him wearing a “red, gray, red” Richmond cap, to judge from the black and white photograph. Howard’s cap has the same type of crossed cannon insignia on the front that the Crenshaw caps have. The jacket and trouser match in color and coarse texture, but they contrast with the cap’s side-piece cloth, which is of a finer texture and lighter color.43

As mentioned, officer caps were often made in the variegated style of the Richmond enlisted caps, and two in particular seem to have copied the Royall cap, “red, gray, red” color scheme. One was owned by Benjamin Pendleton, 2nd Virginia Infantry, “Stonewall Brigade.” Pendleton served with the Stonewall Brigade early in the war, having been Stonewall Jackson’s courier. He was present at the surrender at Appomattox in 1865. His service records indicate that he was a private. His cap and his own account suggest that he may have been unofficially promoted to 2nd Lieutenant. Pendleton’s cap is made of fine scarlet cloth with gold lace on the cadet gray sides and in a knot on the red crown. The composition visor has a layer of pasteboard sandwiched between two layers of leather. The outer edge is machine sewn without a welt. The band is two-piece with a seam in the front. The chinstrap and buttons are missing. The lining and sweatband are not visible in the available photo.44

The other officer cap in a similar color scheme dates to early in the war. It belonged to Lieutenant Charles Ellis Munford, Letcher’s Virginia Artillery. Munford was killed at the Battle of Malvern Hill in 1862. His cap had dark blue sides and a scarlet band and crown made of fine broadcloth. The band, sides and crown have the gold lace and knot for a lieutenant. The two-piece, leather chinstrap is secured with Federal enlisted, eagle “A” buttons. The visor appears to be a composition leather one with a leather welt. The lining and sweatband are not visible in the available photo. Munford’s cap provides tangible evidence that the variegated color scheme was common in Virginia early in the War.

The other officer cap in a similar color scheme dates to early in the war. It belonged to Lieutenant Charles Ellis Munford, Letcher’s Virginia Artillery. Munford was killed at the Battle of Malvern Hill in 1862. His cap had dark blue sides and a scarlet band and crown made of fine broadcloth. The band, sides and crown have the gold lace and knot for a lieutenant. The two-piece, leather chinstrap is secured with Federal enlisted, eagle “A” buttons. The visor appears to be a composition leather one with a leather welt. The lining and sweatband are not visible in the available photo. Munford’s cap provides tangible evidence that the variegated color scheme was common in Virginia early in the War.

The second group of variegated caps includes seven artillery variants with a “cadet gray, red, cadet gray” color scheme. The first of these was worn by Captain Daniel Morgan, of Hart’s South Carolina Horse Artillery Battery, who was killed in 1864. Despite having been an officer, Morgan wore this enlisted cap. The cadet gray fabric is kersey and the red fabric is satinet. The enameled cloth, two-piece chinstrap is intact, but in poor condition. It is secured with one remaining lined, script “I” button (Tice CSI215As). The conforming pattern lining is intact, but the sweatband is missing. Interestingly, the pasteboard stiffener in the band is still intact and is positioned between the basic cloth of the band and the osnaburg lining (that extends to the base).45

The second of these caps was worn by an Army of Northern Virginia soldier: Rice E. Bryan, Company A, 36th Virginia Infantry. Rice was from Buffalo, Virginia (now West Virginia). He enlisted in May 1861 in the "Buffalo Guards" and served with the regiment through the Appomattox campaign in April 1865. Soon after the war, a member of the Fife family, possibly Colonel William E. Fife, 36th Virginia Infantry, acquired the cap. Men from the Fife family were from Putnam and Kanawha Counties, West Virginia, and had served with the 22nd and 36th Virginia Infantry Regiments. It is likely that they were acquainted with Rice E. Bryan. According to a Fife family descendant, Thomas Fife, the family had nicknamed the artifact the “Drummer Boy’s Cap.”

More caps have the “cadet gray, red, cadet gray” variegated color scheme. Three of these have good photos available, but they are without provenance. These caps are in the following collections: Fort Donelson, National Battlefield Park; Texas Civil War Museum; and, Battleground Antiques. All three caps are made of satinet basic cloth, both for the cadet gray and the red components. The Fort Donelson cap is missing most of its chinstrap, only the remnants under the four-hole, tin trouser buttons remain intact.46 The Texas Civil War Museum cap (now in the Tristan Galloway collection) has its two-piece chinstrap intact. The chinstrap is secured with two black japanned, four-hole, trouser buttons.47 The third of these is from Battleground Antiques. This cap has remnants of its chinstrap intact connected to its buttons: lined Roman “A” (Tice CSA203As).48 Only images of the interior for the Tristan Galloway cap are available, it having a conforming style lining.

052a: The Texas collection “cadet gray, red, cadet gray” cap matches the others of this type, being made of Confederate gray and red satinet with white cottons warps. This cap has black horn, four-hole chinstrap buttons. Artifact courtesy of the Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas (now in the Tristan Galloway collection).

053a: The Battleground Antiques “cadet gray, red, cadet gray” cap is nearly identical to the previous two of this type: it is made of cadet, or Confederate gray and red satinet fabrics with white cottons warps. This cap has branch correct, Roman "A", brass chinstrap buttons. Artifact and image courtesy of Will Gorges, Battleground Antiques, New Bern, North Carolina.

The last two caps with the “cadet gray, red, cadet gray” color scheme are somewhat elusive. The first of these two was sold by Deep South Artifacts in about 2002. The available images are indistinct thumbnail photos which makes a detailed analysis impossible. Unfortunately, the business owner, Mr. Keith Kenerly, does not have any better images or records of the cap’s whereabouts.49 The second of these was put on auction by a Roanoke, Virginia antique store dealer in May 1992. According to the store owner’s information and photos, the cap belonged to William Ballard Rowan, 4th Virginia Artillery Battalion. Based on several color photographs viewed just prior to the cap’s auction, the cadet gray fabric may have been satinet, and the red possibly fine woolen cloth. The visor and chinstrap were the typical enameled cloth, and the chinstrap buttons were black japanned metal, four-hole, trouser buttons. None of the photos showed the inside of the cap.50 Unfortunately, the author viewed the photos long before the days of cell phones and was not able to get any images of his own. Moreover, the provenance is sketchy because there is no Confederate record of either a William Ballard Rowan or a 4th Virginia Artillery Battalion. Furthermore, since the trail of ownership is unknown for both of these last two caps, the question arises whether they might not be one of the three caps mentioned in the previous paragraph.

There is only one surviving variegated Richmond infantry cap, but there are several contemporary images that document its existence. The surviving cap was worn by Captain James L. Clark, Company B, 2nd Maryland Cavalry. Clark was wearing the cap when he was captured on August 7, 1864. It is odd that Clark, a cavalry officer, would wear an infantry cap. He may have acquired it through some unexplained fluke. Clark’s cap has a cadet gray kersey band and crown with Confederate, light blue kersey sides. The cap has two rows of gold lace for Clark’s rank, and the gold braid chinstrap has a matching, continuation band around the base of the cap. The buttons are gilted, Louisiana pelican motif (Tice LA223As). The visor is an officer-quality, glazed, leather bound composition style. The interior is lined with black Silesia and a dark dress material with black, brown and gold stripes. The sweatband is russet leather with gold stamping around the top edge. Perhaps this cap was intended for a Louisiana infantry officer who might have fallen before he could pick it up from the tailor, and Clark bought it instead.51

Another cavalry officer’s variegated cap, that of First Lieutenant William H. Harwood’s does not follow any branch color scheme (certainly not the cavalry colors). Harwood served with the 3rd Virginia Cavalry from 1861 through 1865. His cap has dark blue cloth sides, and the crown and band are a steel- or perhaps a sheep’s gray, in a coarse jeans fabric. The cap has gold lace for the rank of lieutenant and infantry, script “I” chinstrap buttons. It might be surmised that Harwood bought the cap at a tailor shop based on size and availability, the tailor not having a cavalry cap in Harwood’s size on hand. One might also presume a late war provenance for the cap since it survived the war.52

A variegated Richmond-style cap worn by Captain Benjamin Chase, 22nd Virginia Infantry has an early war provenance. Chase wore this cap prior to his death at the Battle of Lewisburg, May 23, 1862. Chase’s cap is made in the enlisted style, without gold lace, in a “black, dark gray, black” color scheme. The band and crown fabric are brown velvet, faded from black, and the sides are dark gray broadcloth. The chinstrap is missing, but the cap retains its non-military, brass buttons. The visor is an officer-quality, bound leather type. Chase’s cap might loosely be classed as infantry since infantrymen so frequently used black as a trim color. In any case, the cap points to the early use of the variegated style by soldiers in Virginia.53

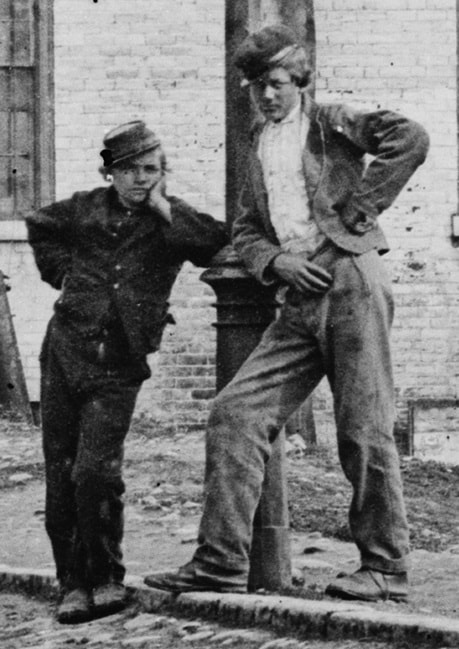

There is actually more evidence for the variegated infantry cap in contemporary photos. These images were taken in Richmond, Virginia, April 1865, after fall of the Confederacy. They depict numerous paroled Confederate soldiers with caps, as well as scores of Richmond boys, who all wore Confederate army caps, taken, no doubt, from the defunct Richmond clothing depot. Some of these caps clearly have the “light blue, cadet gray, light blue” color scheme of the Richmond infantry cap, discernable despite the gray tones of the black and white images.54

Richmond Depot caps have a character about them that I believe the manufacturers purposely affected. Just as the Richmond Depot, during the last part of the war, gave preferential use of cadet gray cloth for jackets, I think authorities likewise desired cadet gray caps. They wanted a degree of uniformity. By using cadet gray cloth for jackets and caps, even if pants varied in texture and shade, the Army of Northern Virginia achieved a uniqueness and uniformity that paralleled the Union army.55 From 1864 onwards, the Army of Northern Virginia had a standard uniform: the cadet gray Richmond cap and jacket. This is what is most fascinating about the Richmond cap. Even though the average Johnny Reb may not have donned it, the Richmond cap is proof that the Southern quartermaster could produce a truly universal uniform for Lee’s army. It reflects a spirit of resilience, discipline, and order under the most trying of circumstances. And, it was accomplished even as the Southern Confederacy was on its last legs, and its army was marching into the jaws of hell.

Copyright: This study and its contents are copyrighted to the Adolphus Confederate Uniforms website with the exception of those images that are part of the Library of Congress collection, or in the public domain.

Click this link to navigate to Part III of this study...

Bibliography

27. These dimensions were taken from the Richmond caps that the author examined and measured.

28. Howard, McHenry, Recollections of a Maryland Confederate Soldier and Staff Officer Under Johnston, Jackson and Lee, Morningside Bookshop, Dayton, Ohio, 1975, pp. 354-355 note 360, 454-455 note 355, 368 & 388; A brigade of six battalions of heavy artillery were armed with muskets under the command of Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield. The battalions included the 10th and 19th Virginia Battalions, the 18th and 20th Virginia Battalions, the 18th Georgia Battalion, and one other. (pp. 354-355) This unit was formed in the spring of 1865, (see also p. 360, note 11, and pp. 454-455, note from p. 355). Crutchfield’s Heavy Artillery Brigade numbered about 1,400. “The heavy artillerymen having been stationary around Richmond had been able to keep their uniforms in better plight, and their scarlet caps and trimmings (artillery color) made them present a distinctive appearance to the army, of which they were now a regular part,” (p. 368, April 1865). Regarding the retreat from Richmond (p. 388), the heavy artillery was distinctive by its bravery and uniforms, “In fact, it is evident to me that the fresher and variegated caps and uniforms of the heavy artillerymen made the enemy suppose they belonged to the ‘Navy Brigade’ or battalion,…” The reference to the Maryland prisoners is taken from The Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman: From the Wilderness to Appomattox, 1922, p. 221.

29. Jones, John B., A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary, Volume I, Time Life, 1982 reprint of the original Lippincott, 1866 publication; Crenshaw’s woolen prices on February 1, 1863, p. 252, Vol. I, (hereafter, J.B. Jones).

30. Richmond Enquirer, 17 October 1861.

31. This data is drawn from the independent research of C.L. Webster. Webster drew on the National Archives, Record Group 109, Confederate Papers Relating Citizens or Business Firms, 1861-65, Microcopy 346 (hereafter, CSA Citizens M346, with appropriate roll number and reference), from the following: Frank Binford, Roll 65; Martin Brittain, Roll 98; F.M. Burford, Roll 120; Robert L. Dickinson, Roll 246; Henry Domler, Roll 252; Ellet & Weisiger, Roll 280; Charles L. McIndoe, Roll 632; Mary R. McIndoe, Roll 632; Thomas L. Pugh, Roll 826; I.C. Rittenhouse, Roll 868.

32. CSA Citizens M346, Roll 65, Frank Binford.

33. CSA Officers M346, Roll 186 and CSA Citizens M346, Roll 186, A representative invoice for cap fronts is one paid by Captain F.W. Dillard, Quartermaster, Columbus, Georgia Depot. On 5 December 1863, Dillard bought 8,823 cap visors from the Columbus Knitting Company for $4,852.65.

34. CSA Citizens M346, Roll 65, Frank Binford. Furthermore, the first large-scale shipments of imported, cadet gray kersey arrived at Richmond in the spring of 1863. The first uniforms made of this cloth were issued to Army of Northern Virginia troops in May 1863. During August, the cadet gray jackets were issued en masse to the army, along with pants made of imported, light-blue kersey.

35. Wilson, Harold S., Confederate Industry: Manufacturers and Quartermasters in the Civil War, University of Mississippi Press, Jackson, 2002, (hereafter, Wilson), p. 127, from The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 4, Volume 3, pp. 1039-1041, (hereafter, OR, with appropriate Series, Volume, Part, Chapter and pages), A.R. Lawton, C.S. Quartermaster General’s Office, Richmond, reported to Hon. Mr. Miller, Chairman Special Committee, on 27 January 1865, the field issues to the Army of Northern Virginia during the 3rd and 4th quarters of 1864, and up to 21 January 1865. These issues included 27,011 hats and caps.

36. Artifact and images courtesy of the New York State Division of Military Affairs, Military History Collection, Catalog Number CM 1995-5011. The author examined the cap in April 2009. This cap is featured in Echoes of Glory, Arms and Equipment of the Confederacy, Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia, 1991, p. 156.

37. Artifacts and images courtesy of Gary Hendershott Museum Consultants, Little Rock, Arkansas, Gladium II Catalog, 2011, Lot #15, and Civil War Catalog, Sale 140, October 2008, Lot #216, (hereafter, Hendershott, with applicable reference).

38. Artifact and images courtesy of The Horse Soldier, 219 Steinwehr Avenue, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, online catalog 2008.

39. Artifact courtesy the Miller-Kite House, Elkton, Virginia; images courtesy of Greg Starbuck.

40. Artifact courtesy of the Pittsylvania Historical Society collection, Chatham, Virginia; images courtesy of Greg Starbuck.

41. Artifact and images courtesy of Hendershott, Gladium III Catalog, Sale 153, Lot #2016; and, the American Civil War Museum (artifact only).

42. Bell Irvin Wiley, Embattled Confederates, Bonanza Books, New York, 1964, p. 104, Crenshaw image of Farrell, MOC collection; see also article in NSTCW, Volume 36, No. 2, 2012, Serrano, p. 34; Leslie D. Jensen, Johnny Reb, The Uniform of the Confederate Army, 1861-1865, Greenhill Books, London & Stackpole Books, Pennsylvania, 1996, p. 52, unidentified Crenshaw image, Jensen declined to share the source.

43. Jensen, Leslie D., A Survey of Confederate Central Government Quartermaster Issue Jackets, Part II, Military Collector & Historian, Vol. XLI, No. 4, Fall & Winter 1989, (hereafter, Jensen, Survey, Part II).

44. Artifact and image courtesy of Hendershott, Civil War Catalog, Sale 140, October 2008, Lot #213.

45. Artifact courtesy of the South Carolina Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina. The author examined the cap on 29 June 2002.

46. Artifact and image courtesy of Fort Donelson National Battlefield, Dover, Tennessee.

47. Artifact courtesy of the Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas. The author viewed the artifact in May 2008 and January 2009.

48. Artifact and image courtesy of Battleground Antiques, Will Gorges, New Bern, North Carolina, website, ca November 2015.

49. Artifact and photos courtesy of Deep South Artifacts, Inc., Keith B. Kenerly, Fredericksburg, Virginia, website, 5 February 2002. Artist color sketch courtesy of Alan Archambault.

50. Roanoke Antique Store, the author viewed the auction color photographs on 19 and 20 May 1992.

51. Artifact courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia. The author examined the cap on 15 October 2013.

52. Collection unknown; CSRs Virginia, M324, Roll 30.

53. Artifact and image courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

54. Images are courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. (hereafter, Library of Congress).

55. The disproportionally high numbers of surviving original, cadet gray jackets, pants and caps from the Army of Northern Virginia bear out this assertion.

Copyright: This study and its contents are copyrighted to the Adolphus Confederate Uniforms website with the exception of those images that are part of the Library of Congress collection, or in the public domain.

Click this link to navigate to Part III of this study...

Bibliography

27. These dimensions were taken from the Richmond caps that the author examined and measured.

28. Howard, McHenry, Recollections of a Maryland Confederate Soldier and Staff Officer Under Johnston, Jackson and Lee, Morningside Bookshop, Dayton, Ohio, 1975, pp. 354-355 note 360, 454-455 note 355, 368 & 388; A brigade of six battalions of heavy artillery were armed with muskets under the command of Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield. The battalions included the 10th and 19th Virginia Battalions, the 18th and 20th Virginia Battalions, the 18th Georgia Battalion, and one other. (pp. 354-355) This unit was formed in the spring of 1865, (see also p. 360, note 11, and pp. 454-455, note from p. 355). Crutchfield’s Heavy Artillery Brigade numbered about 1,400. “The heavy artillerymen having been stationary around Richmond had been able to keep their uniforms in better plight, and their scarlet caps and trimmings (artillery color) made them present a distinctive appearance to the army, of which they were now a regular part,” (p. 368, April 1865). Regarding the retreat from Richmond (p. 388), the heavy artillery was distinctive by its bravery and uniforms, “In fact, it is evident to me that the fresher and variegated caps and uniforms of the heavy artillerymen made the enemy suppose they belonged to the ‘Navy Brigade’ or battalion,…” The reference to the Maryland prisoners is taken from The Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman: From the Wilderness to Appomattox, 1922, p. 221.

29. Jones, John B., A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary, Volume I, Time Life, 1982 reprint of the original Lippincott, 1866 publication; Crenshaw’s woolen prices on February 1, 1863, p. 252, Vol. I, (hereafter, J.B. Jones).

30. Richmond Enquirer, 17 October 1861.

31. This data is drawn from the independent research of C.L. Webster. Webster drew on the National Archives, Record Group 109, Confederate Papers Relating Citizens or Business Firms, 1861-65, Microcopy 346 (hereafter, CSA Citizens M346, with appropriate roll number and reference), from the following: Frank Binford, Roll 65; Martin Brittain, Roll 98; F.M. Burford, Roll 120; Robert L. Dickinson, Roll 246; Henry Domler, Roll 252; Ellet & Weisiger, Roll 280; Charles L. McIndoe, Roll 632; Mary R. McIndoe, Roll 632; Thomas L. Pugh, Roll 826; I.C. Rittenhouse, Roll 868.

32. CSA Citizens M346, Roll 65, Frank Binford.

33. CSA Officers M346, Roll 186 and CSA Citizens M346, Roll 186, A representative invoice for cap fronts is one paid by Captain F.W. Dillard, Quartermaster, Columbus, Georgia Depot. On 5 December 1863, Dillard bought 8,823 cap visors from the Columbus Knitting Company for $4,852.65.

34. CSA Citizens M346, Roll 65, Frank Binford. Furthermore, the first large-scale shipments of imported, cadet gray kersey arrived at Richmond in the spring of 1863. The first uniforms made of this cloth were issued to Army of Northern Virginia troops in May 1863. During August, the cadet gray jackets were issued en masse to the army, along with pants made of imported, light-blue kersey.

35. Wilson, Harold S., Confederate Industry: Manufacturers and Quartermasters in the Civil War, University of Mississippi Press, Jackson, 2002, (hereafter, Wilson), p. 127, from The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 4, Volume 3, pp. 1039-1041, (hereafter, OR, with appropriate Series, Volume, Part, Chapter and pages), A.R. Lawton, C.S. Quartermaster General’s Office, Richmond, reported to Hon. Mr. Miller, Chairman Special Committee, on 27 January 1865, the field issues to the Army of Northern Virginia during the 3rd and 4th quarters of 1864, and up to 21 January 1865. These issues included 27,011 hats and caps.

36. Artifact and images courtesy of the New York State Division of Military Affairs, Military History Collection, Catalog Number CM 1995-5011. The author examined the cap in April 2009. This cap is featured in Echoes of Glory, Arms and Equipment of the Confederacy, Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia, 1991, p. 156.

37. Artifacts and images courtesy of Gary Hendershott Museum Consultants, Little Rock, Arkansas, Gladium II Catalog, 2011, Lot #15, and Civil War Catalog, Sale 140, October 2008, Lot #216, (hereafter, Hendershott, with applicable reference).

38. Artifact and images courtesy of The Horse Soldier, 219 Steinwehr Avenue, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, online catalog 2008.

39. Artifact courtesy the Miller-Kite House, Elkton, Virginia; images courtesy of Greg Starbuck.

40. Artifact courtesy of the Pittsylvania Historical Society collection, Chatham, Virginia; images courtesy of Greg Starbuck.

41. Artifact and images courtesy of Hendershott, Gladium III Catalog, Sale 153, Lot #2016; and, the American Civil War Museum (artifact only).

42. Bell Irvin Wiley, Embattled Confederates, Bonanza Books, New York, 1964, p. 104, Crenshaw image of Farrell, MOC collection; see also article in NSTCW, Volume 36, No. 2, 2012, Serrano, p. 34; Leslie D. Jensen, Johnny Reb, The Uniform of the Confederate Army, 1861-1865, Greenhill Books, London & Stackpole Books, Pennsylvania, 1996, p. 52, unidentified Crenshaw image, Jensen declined to share the source.

43. Jensen, Leslie D., A Survey of Confederate Central Government Quartermaster Issue Jackets, Part II, Military Collector & Historian, Vol. XLI, No. 4, Fall & Winter 1989, (hereafter, Jensen, Survey, Part II).

44. Artifact and image courtesy of Hendershott, Civil War Catalog, Sale 140, October 2008, Lot #213.

45. Artifact courtesy of the South Carolina Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina. The author examined the cap on 29 June 2002.

46. Artifact and image courtesy of Fort Donelson National Battlefield, Dover, Tennessee.

47. Artifact courtesy of the Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas. The author viewed the artifact in May 2008 and January 2009.

48. Artifact and image courtesy of Battleground Antiques, Will Gorges, New Bern, North Carolina, website, ca November 2015.

49. Artifact and photos courtesy of Deep South Artifacts, Inc., Keith B. Kenerly, Fredericksburg, Virginia, website, 5 February 2002. Artist color sketch courtesy of Alan Archambault.

50. Roanoke Antique Store, the author viewed the auction color photographs on 19 and 20 May 1992.

51. Artifact courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia. The author examined the cap on 15 October 2013.

52. Collection unknown; CSRs Virginia, M324, Roll 30.

53. Artifact and image courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

54. Images are courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. (hereafter, Library of Congress).

55. The disproportionally high numbers of surviving original, cadet gray jackets, pants and caps from the Army of Northern Virginia bear out this assertion.