Confederate Uniforms of the Lower South, Part III: Georgia and the Army of Tennessee

By Fred Adolphus, August 18, 2019

By Fred Adolphus, August 18, 2019

Continued from Part II: click here to navigate back to the previous page...

Having described the uniforms of East Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama, I now move eastwards to discuss the uniforms of Georgia, Florida and South Carolina.

Just as New Orleans and Baton Rouge initially served as the western Lower South’s manufacturing base, so were Nashville and Memphis to the Upper Western South. The quartermaster operations in Tennessee have been discussed in the first part of this study, but it is noteworthy that two of the key officers in the Tennessee quartermaster operation became key players in the Lower South: Cunningham set up operations in Atlanta and Anderson managed a large operation in Jackson and Columbus, Mississippi. The large manufacturing centers in the Lower South filled the roles that Nashville and Memphis had played the first year of the war. The new industrial centers of Atlanta, Columbus (Georgia), Augusta and Charleston implemented high degrees of uniformity and production by mid-1862. This reflected well on of the efficiency of the Tennessee and New Orleans quartermasters who had shifted their operations, and their talents, further within Confederate lines.

Identifying all the uniforms associated with the Georgia and South Carolina region is problematic. Uniforms from the larger depots are easier to identify. For instance, the prolific “Columbus Depot” uniform consisting of a gray jeans jacket with straight cuff facings and matching short collar has good provenance to the Columbus-Atlanta clothing operations.[122] Likewise, the blue-gray jackets with plumb, left collars have well-documented provenance to the Charleston-Augusta clothing depots. However, the diverse jackets with provenance to the Army of Tennessee and Georgia that do not conform to an identifiable typology are more difficult to identify. These may have been products of small firms that were not permanently engaged in the making of clothing, or even ad hoc quartermaster operations in Athens, Savannah, Richmond and Milledgeville. Furthermore, the State of Georgia’s “Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau” at Augusta manufactured significant quantities of clothing for its militia and for Georgia troops in Confederate service. With so many potential sources for uniforms, it is befuddling to speculate about who may have made which surviving jacket. Indeed, archival records are sparse, and the bigger picture must be pieced together with fragmentary accounts. Even the assumption that every depot or factory made a different style of jacket is tenuous. Given Major George W. Cunningham’s organizational efficiency and his penchant for cooperation (Cunningham ran the Atlanta Depot), it is likely that the Atlanta and Columbus depots made the exact same soldier suit, known today as the “Columbus” Depot jacket. I would call this uniform the “Columbus-Atlanta” Depot uniform. In fact, the Columbus jacket may very well be the “Western tunic” described by Lieutenant Colonel Gilbert Moxley Sorrel of Longstreet’s staff at Chickamauga. Sorrel remarked that the jackets worn by the Army of Tennessee troops were very distinct from those of the Army of Northern Virginia soldiers, “The personal appearance of Bragg’s army was, of course, a matter of interest to us of Virginia. The men were a fine-looking lot, strong, lean, long-limbed fighters. The Western tunic was much worn by both officers and men. It is an excellent garment, and its use could be extended with much advantage.”[123] All in all, the diversity of the region’s jacket types suggests that numerous small factories contributed much to the quartermaster’s aggregate supply of uniforms, much as was the case in Alabama and Mississippi.

Georgia’s Confederate clothing bureau was similar to that of Mississippi and Alabama in that the products of several depots (Atlanta, Columbus, Augusta, and other smaller operations) were often pooled together indiscriminately and issued based on authorized requisitions. For the most part, however, the Columbus and Atlanta Depots supplied the Army of Tennessee, while the Augusta Depot usually supplied the forces along the South Carolina and Georgia coast. All these depots supplied the Army of Northern Virginia, and other armies, from time to time. For instance, Major Francis W. Dillard, Quartermaster at the Columbus Depot, shipped his monthly production for June 1862, amounting to 240 wooden boxes of uniforms, to the Richmond Depot for the Army of Northern Virginia.[124] That autumn, Dillard sent clothing not only to the Army of Tennessee, but to forces in Virginia, Mississippi and Arkansas. Accordingly, Tilgman’s division in Mississippi received new clothes in November 1862 from Columbus, Georgia that gave his men a, “fine appearance… they had on gray caps and coats with sky blue pants. The coats are roundabouts – the cuffs and collars trimmed with blue…” The Columbus Daily Sun newspaper reported that the Columbus quartermaster’s department sent out during the fall six car loads of clothing and shoes to the army at Richmond, Virginia; 5,000 garments to the Army of Western Virginia; 30,000 garments to General “Tilgham” [Tilgman in Mississippi]; 17,000 garments to Bragg’s Army [of Tennessee]; 3,000 garments to Texas Rangers [presumably also in Bragg’s army]; and, 7,000 garments to Army of Arkansas.[125] The aggregate production of clothing bureau in Georgia was enormous, and kept the armies generally well clothed throughout the war.

Having described the uniforms of East Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama, I now move eastwards to discuss the uniforms of Georgia, Florida and South Carolina.

Just as New Orleans and Baton Rouge initially served as the western Lower South’s manufacturing base, so were Nashville and Memphis to the Upper Western South. The quartermaster operations in Tennessee have been discussed in the first part of this study, but it is noteworthy that two of the key officers in the Tennessee quartermaster operation became key players in the Lower South: Cunningham set up operations in Atlanta and Anderson managed a large operation in Jackson and Columbus, Mississippi. The large manufacturing centers in the Lower South filled the roles that Nashville and Memphis had played the first year of the war. The new industrial centers of Atlanta, Columbus (Georgia), Augusta and Charleston implemented high degrees of uniformity and production by mid-1862. This reflected well on of the efficiency of the Tennessee and New Orleans quartermasters who had shifted their operations, and their talents, further within Confederate lines.

Identifying all the uniforms associated with the Georgia and South Carolina region is problematic. Uniforms from the larger depots are easier to identify. For instance, the prolific “Columbus Depot” uniform consisting of a gray jeans jacket with straight cuff facings and matching short collar has good provenance to the Columbus-Atlanta clothing operations.[122] Likewise, the blue-gray jackets with plumb, left collars have well-documented provenance to the Charleston-Augusta clothing depots. However, the diverse jackets with provenance to the Army of Tennessee and Georgia that do not conform to an identifiable typology are more difficult to identify. These may have been products of small firms that were not permanently engaged in the making of clothing, or even ad hoc quartermaster operations in Athens, Savannah, Richmond and Milledgeville. Furthermore, the State of Georgia’s “Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau” at Augusta manufactured significant quantities of clothing for its militia and for Georgia troops in Confederate service. With so many potential sources for uniforms, it is befuddling to speculate about who may have made which surviving jacket. Indeed, archival records are sparse, and the bigger picture must be pieced together with fragmentary accounts. Even the assumption that every depot or factory made a different style of jacket is tenuous. Given Major George W. Cunningham’s organizational efficiency and his penchant for cooperation (Cunningham ran the Atlanta Depot), it is likely that the Atlanta and Columbus depots made the exact same soldier suit, known today as the “Columbus” Depot jacket. I would call this uniform the “Columbus-Atlanta” Depot uniform. In fact, the Columbus jacket may very well be the “Western tunic” described by Lieutenant Colonel Gilbert Moxley Sorrel of Longstreet’s staff at Chickamauga. Sorrel remarked that the jackets worn by the Army of Tennessee troops were very distinct from those of the Army of Northern Virginia soldiers, “The personal appearance of Bragg’s army was, of course, a matter of interest to us of Virginia. The men were a fine-looking lot, strong, lean, long-limbed fighters. The Western tunic was much worn by both officers and men. It is an excellent garment, and its use could be extended with much advantage.”[123] All in all, the diversity of the region’s jacket types suggests that numerous small factories contributed much to the quartermaster’s aggregate supply of uniforms, much as was the case in Alabama and Mississippi.

Georgia’s Confederate clothing bureau was similar to that of Mississippi and Alabama in that the products of several depots (Atlanta, Columbus, Augusta, and other smaller operations) were often pooled together indiscriminately and issued based on authorized requisitions. For the most part, however, the Columbus and Atlanta Depots supplied the Army of Tennessee, while the Augusta Depot usually supplied the forces along the South Carolina and Georgia coast. All these depots supplied the Army of Northern Virginia, and other armies, from time to time. For instance, Major Francis W. Dillard, Quartermaster at the Columbus Depot, shipped his monthly production for June 1862, amounting to 240 wooden boxes of uniforms, to the Richmond Depot for the Army of Northern Virginia.[124] That autumn, Dillard sent clothing not only to the Army of Tennessee, but to forces in Virginia, Mississippi and Arkansas. Accordingly, Tilgman’s division in Mississippi received new clothes in November 1862 from Columbus, Georgia that gave his men a, “fine appearance… they had on gray caps and coats with sky blue pants. The coats are roundabouts – the cuffs and collars trimmed with blue…” The Columbus Daily Sun newspaper reported that the Columbus quartermaster’s department sent out during the fall six car loads of clothing and shoes to the army at Richmond, Virginia; 5,000 garments to the Army of Western Virginia; 30,000 garments to General “Tilgham” [Tilgman in Mississippi]; 17,000 garments to Bragg’s Army [of Tennessee]; 3,000 garments to Texas Rangers [presumably also in Bragg’s army]; and, 7,000 garments to Army of Arkansas.[125] The aggregate production of clothing bureau in Georgia was enormous, and kept the armies generally well clothed throughout the war.

Major George W. Cunningham’s Atlanta Depot, in March 1863, had fully supplied the Army of Tennessee with clothing (excepting shoes), with an additional 6,000 uniforms available in storage at Chattanooga. Atlanta Quartermaster Major V.K. Stevenson (working alongside Cunningham from early 1862 through April 1863), also reported large stocks of clothing on hand in April, in Atlanta, to include: 25,000 jackets or roundabouts, woolen; 15,000 pairs pants, woolen; 65,000 cotton shirts; 30,000 cotton drawers; 2,000 blankets; 4,000 pairs shoes; and, 3,800 wool hats. Stevenson also reported having 90,000 yards of woolen cloth and 135,000 yards of wool jean material. By April, the army was reported to have been “tolerably well shod.” Cunningham’s production during the last quarter of 1862 included: 37,150 jackets; 13,430 pairs pants; 13,700 pairs cotton drawers; 10,475 cotton shirts; and, 1,500 flannel shirts. His first quarter 1863 production was: 33,960 pairs of pants; 34,992 pairs cotton drawers; 89,245 cotton shirts; and, 1,160 flannel shirts. During March 1863, he began manufacturing his shoes, with the first month’s production at 3,285 pairs.[126] By mid-1864, Cunningham was contracting for enough cottons and woolens to make 20,000 uniforms monthly.[127] Cunningham suspended operations in Atlanta in June 1864 due to the proximity of the Federal army. He evacuated his operation to Augusta. He tried to rebuild the Atlanta Depot in March 1865, but he was unable to acquire the cotton goods that he needed.[128] No contemporary description of Cunningham’s Atlanta uniform has survived, but he reported that James Barrington King’s Ivy woolen mill at Roswell supplied the Army of Tennessee (he probably was referring to his Atlanta depot) with between 12,000 and 15,000 yards of woolen jeans per month, from which about half of his Atlanta Depot uniforms were made.[129]

The largest Confederate quartermaster complex in the Western theater was the Columbus, Georgia Depot, co-located with numerous private factories. Major Francis W. Dillard managed this depot from August 1861 to the end of the war.[130] From October 1, 1861 to May 1864 the depot made 305,065 pairs of shoes; 263,922 jackets; 290,092 pair pants; 116,146 shirts; 82,948 drawers; and, 122,441 caps.[131] The Eagle Manufacturing Company was the largest single factory in Columbus, and it furnished the Confederacy with an array of materiel. The Eagle Factory made India rubber cloth until June 1862, after which time it made enameled cloth for the rest of the war. The factory-made cottons to include muslin, osnaburg, shirting, and 10-ounce cotton duck. It was the largest supplier of woolens in the Lower South, amounting to three-quarters of Cunningham’s woolen garment production. The factory’s total sales to the quartermaster during the six-month period ending in May 1864 was 296,000 yards. Sales receipts are mainly for “Georgia Cassimere,” which the factory provided from at least June 1862 until September 1864. This fabric was also referred to as “woollen jeans” in 1863. The factory also provided “coat and pants goods,” from June to September 1864: an inexpensive fabric compared to the more highly-priced cassimere. In 1865, the Eagle factory made 2,200 yards of woolen jeans per day.[132] Union General William T. Sherman bypassed both Augusta and Columbus on his march through Georgia, November-December 1864, but Federal cavalry laid waste to Columbus on April 16, 1865. When Union troops seized Dillard’s depot, it had 4,500 suits of Confederate uniform; 5,890 yards of army jeans; 1,000 yards osnaburgs; 8,820 pairs of shoes; 4,750 pairs of cotton drawers; 1,700 gray jackets; 4,700 pairs of pants; 2,000 pairs of socks; 400 shirts; and, 650 gray caps. This inventory provides a glimpse of what Dillard issued to the Confederate army. The Federals burned Dillard’s manufacturing depot, the Eagle Factory, as well as four cotton factories, a sock factory, a shoe factory, and two other oil cloth factories (besides the Eagle Factory). Again, the list of destruction offers insights into what the manufacturing complex was making for the quartermaster department.[133]

Augusta was the third of Georgia’s three large manufacturing complexes. It bears mentioning that although Augusta is geographically part of Georgia, it generally supplied the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida: the region along these states’ Atlantic coast. Major Isaac T. Winnemore managed the Confederate depot there, having moved from New Orleans when the city fell in April 1862.[134] It was not until October 1862, however, that the depot began full-fledged manufacturing. In that month, Major Lemuel O. Bridewell was assigned there to establish a clothing depot. Bridewell manufactured the first soldier suits of jackets and pants from 23,000 yards of captured Kentucky jeans that General Braxton Bragg had sent to Augusta the same month that Bridewell arrived. Bragg had seized 150,000 yards of jeans and linseys during the Kentucky campaign from Oldham Scott & Company, Lexington, Kentucky. By December 2, 1862, Bridewell had manufactured approximately five thousand soldier suits out of the Kentucky jeans for Bragg’s army.[135] By December, the new clothing factory was busily engaged in making coats and pants (planning to expand the line to shirts and drawers soon thereafter), and furnished employment to numerous cutters and needlewomen.[136]

Details of the Augusta Depot’s clothing are sparse, but some conclusions might be drawn from the materials that Bridewell used. During the second quarter of 1863, Bridewell accounted for the following clothing (both expenditures and remaining stock on hand): 22,307 pair pants; 43,929 shirts; 16,444 coats; 44,939 pair drawers. Likewise, he accounted for the materials that he used in manufacturing his clothing. The following are the chief items in the inventory, the sum of both expenditures and remaining stock on hand. Bridewell’s button stocks included 885 1/3 gross of coat buttons [127,488 or enough for 21,248 six-button jackets]; 3,574 7/12 gross of pant buttons [514,740 or enough for 46,795 pair pants @ 11 buttons per]; 7,357 gross of agate buttons [1,059,408, for shirts and possibly drawers]; 600 gross of jacket buttons [86,400 or enough for 14,400 six-button jackets]; 85 gross of S.C. buttons [South Carolina?], 12,240 or enough for 2,040 six-button jackets]; 11 2/3 dozen brass buttons; and, 227 gross of pant buckles [32,688]. His cloth inventory included 23,340 ¼ yards of wool jeans (and other types); 49,439 7/8 yards of plain kersey; 76,421 7/8 yards of osnaburgs; 56,409 yards of drillings; 190,414 yards of 7/8 width shirtings; 5,400 yards of 3/4 width shirtings; 6,650 yards of red and blue flannel; 336 yards of bunting; 49,689 yards of hickory stripes; 1,118 ¾ yards of cottonade; 8,034 7/8 yards of assorted gray cloth.[137]

Following the Atlanta Campaign, Augusta supplied Hood’s army with clothing since the Army of Tennessee was cut off from Columbus, Georgia. During October and November 1864, the Augusta quartermaster supplied Hood’s army with an estimated 48,408 jackets; 58,305 pairs of pants; 63,356 pairs of shoes; 37,910 shirts; 41,561 pairs of drawers; 60,800 pairs of socks; and, a supply of blankets. This quantity of clothing reflects the scope of the Augusta’s clothing operation, although part of this inventory may have included stocks transferred from Atlanta to Augusta that summer.[138] The Augusta Depot was co-located with several vital factories, as well. Adam Johnson’s Richmond factory manufactured cloth in 1861 “of a cotton and wool mixture” for winter uniforms. Johnson sold these goods to the Richmond, Virginia clothing bureau that year.[139] In August 1862, William E. Jackson’s Augusta factory was an important supplier of cotton goods to both the Atlanta and Richmond Depots, providing sheeting, brown drills, osnaburgs, muslin and shirting (the last for shirts and sand bags).[140] In August 1864, the Augusta factory was the largest supplier of cottons to the Richmond Clothing Bureau, and by May 1864, the Augusta factory provided Cunningham at the Atlanta Depot with half of his cotton goods.[141] Bridges & Ausley of Augusta, established in 1863, was one of the three main Confederate sock factories by the end of the war. Bridges and Ausley furnished Confederate quartermaster with an estimated 240,000 pairs of socks annually.[142] Not only was Augusta a major industrial center, it was one of the only two places in the state still manufacturing clothing by November 1864, (the other being Columbus).[143]

The total quartermaster “field” issues for the Army of Tennessee from July 1, 1864 to January 1, 1865, as reported by the Quartermaster General, were substantial, and did not include issues to men in hospitals, on furlough, detailed at the posts, to officers, or to men who were paroled, exchanged or retired. These issues were made chiefly from the three large Georgia depots: Atlanta, Columbus and Augusta, amounting to: 45,412 jackets; 102,864: pairs of pants; 102,558 pairs of shoes; 27,900 blankets; 61,860 cotton shirts; 45,853 hats and caps; 108,937 pairs of drawers; and, 55,560 pairs of socks.[144]

Smaller operations also made important contributions. John S. Linton’s Athens factory was “engaged in making cloth, for the Georgia companies, on the coast,” (among these General Alexander Lawton’s troops) in 1861. Once Linton fulfilled his obligations to provide Georgia troops with cloth in January 1862, he offered to furnish the Confederate quartermaster with cloth. On 7 June 1861, the Athens factory had also offered to furnish from one to five thousand [soldier] suits.[145] The Athens mill was still selling the Confederate quartermaster woolens in 1864, having furnished 12,958 yards in the six-month period ending in May.[146] This evidence suggests that Linton may have provided modest quantities of uniforms and woolens throughout the war. The firm at Dalton, Georgia, Rinker & Saum, also sold clothing to the quartermaster. On December 20, 1862, they sold 503 jeans jackets (at prices ranging between $14.00, $14.50 and $15.00 each); 778 jeans pants (at various prices including $12.00, $12.50 and $13.00); and, 25 jeans coats at $18.00 each. The varying prices of the jackets and pants suggests differences in quality or materials, or even trim or button type.[147] There was another small clothing manufacturing depot in Macon.[148] The modest production of the State of Florida also added to the overall supply. Florida may have had only one significant cloth mill: William Bailey’s Monticello factory that was in operation during June 1864. Bailey sold his woolens, and much of his osnaburgs, to the State of Florida to clothe Florida troops in Confederate service. Some uniforms may have been manufactured in Florida, as well, as the Richmond Enquirer reported on November 28, 1862, that the trains took two weeks to move thirteen boxes of clothing and shoes from Florida to Dalton, Georgia.[149]

The final element in Georgia’s clothing operation was the Georgia State quartermaster operation. This included the Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau, and the Georgia Relief and Hospital Association. The state quartermaster established the Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau in October 1862 in Augusta. By the winter of 1862-63, the Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau was making 500 garments a day. This clothing was inspected, and if accepted, it was marked with an ink-stamp, “Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau, Augusta, Ga.” Accepted garments were then boxed and sent to Georgia troops in either the Confederate or the state service. From October 1862 through September 15, 1863, the bureau produced 55,000 pairs of pants, 37,000 jackets, 65,000 pairs of drawers, and 70,000 shirts. Its field issues during 1863 included 5,838 hats, 43,728 jackets, 46,325 pants, 32,181 shirts, 30,068 drawers, 23,756 pairs of shoes, and 4,473 pair socks. In November 1863, the bureau had on hand 4,719 hats, 7,291 jackets, 8,828 pants, 9,185 shirts, 8,036 drawers, 12,293 pairs of shoes, and 7,517 pair socks.[150] The Quartermaster General of Georgia, Ira R. Foster, reported on January 30, 1864 that the State of Georgia had issued to Georgia troops in Confederate service (all armies), “about 15,000 suits clothing and about 30,000 pair of shoes” during that winter. These had been either manufactured by or contracted for by the state.[151] One can infer that the balance of the clothing not furnished to Georgia troops in Confederate service went to state militia troops, detailed soldiers, troops in hospitals and the like. Confederate Quartermaster General, A.R. Lawton, also noted the State of Georgia’s contributions to troops in Confederate service for the year of 1864. These included 26,745 jackets, 28,808 pairs of pants, 37,657 pairs of shoes, 7,504 blankets, 24,952 shirts, 24,168 pairs of drawers, and, 23,024 pairs of socks.[152] Part of this was a consignment of 3,000 uniforms of “Joe Brown Clothes” sent to the Georgia brigades of Longstreet’s Corps at Morristown, Tennessee in March 1864. These uniforms were described being a “dingie white” color. In the Spring of 1864, the bureau sent between 5,000 and 7,000 uniforms to the Army of Tennessee.[153] Overall, the Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau made substantial contributions of clothing during the war.

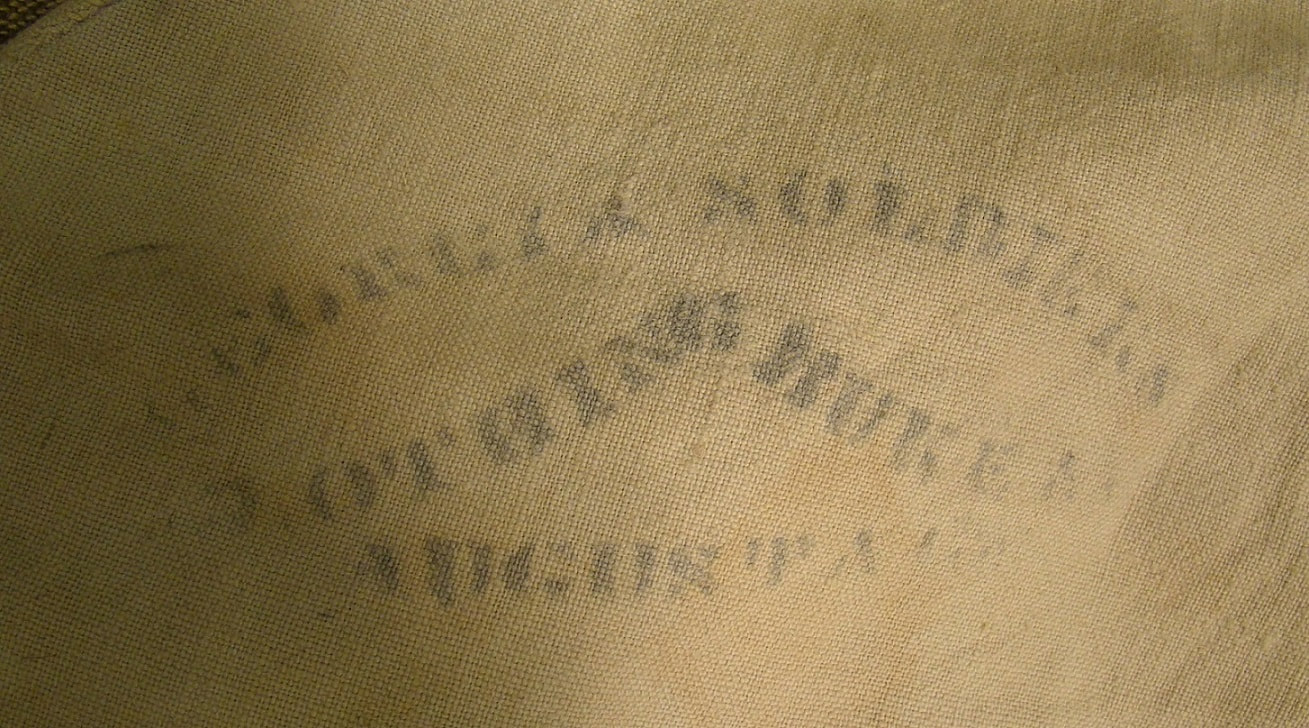

The most significant surviving Georgia Soldiers Clothing Bureau (GSCB) artifact is a pair of trousers owned by John McNish Hazlehurst. These pants are ink-stamped with the GSCB’s name which conclusively proves their provenance to the Georgia State quartermaster operation. Hazlehurst was a seventeen-year-old cadet from Georgia Military Institute who fought with the Georgia Battalion of Cadets in the Army of Tennessee from the spring of 1864 until May 1865. Hazlehurst, and perhaps the entire cadet battalion, appears to have been issued Georgia State clothing during his active service. The pants themselves are made from coarse, plain woven fabric. The warp is a heavy cotton yarn, natural white in color, and the weft is a warm, medium brown wool yarn. The wool appears to have been either dyed brown or spun from brown colored wool fibers. The white and brown yarns together give the fabric an overall light brown color. The pants have side seam pockets, a five-button fly, and six suspender buttons at the waistband. All the trouser buttons match: natural-white bone buttons. The adjustment belt under the rear waist seam has the buckle component on the left (a brass swivel buckle), and the tongue on the right. The lining pieces are made entirely of osnaburgs, and the ink stamp is positioned on the left pocket bag: “GEORGIA SOLDIERS CLOTHING BUREAU AUGUSTA G.”[154]

The largest Confederate quartermaster complex in the Western theater was the Columbus, Georgia Depot, co-located with numerous private factories. Major Francis W. Dillard managed this depot from August 1861 to the end of the war.[130] From October 1, 1861 to May 1864 the depot made 305,065 pairs of shoes; 263,922 jackets; 290,092 pair pants; 116,146 shirts; 82,948 drawers; and, 122,441 caps.[131] The Eagle Manufacturing Company was the largest single factory in Columbus, and it furnished the Confederacy with an array of materiel. The Eagle Factory made India rubber cloth until June 1862, after which time it made enameled cloth for the rest of the war. The factory-made cottons to include muslin, osnaburg, shirting, and 10-ounce cotton duck. It was the largest supplier of woolens in the Lower South, amounting to three-quarters of Cunningham’s woolen garment production. The factory’s total sales to the quartermaster during the six-month period ending in May 1864 was 296,000 yards. Sales receipts are mainly for “Georgia Cassimere,” which the factory provided from at least June 1862 until September 1864. This fabric was also referred to as “woollen jeans” in 1863. The factory also provided “coat and pants goods,” from June to September 1864: an inexpensive fabric compared to the more highly-priced cassimere. In 1865, the Eagle factory made 2,200 yards of woolen jeans per day.[132] Union General William T. Sherman bypassed both Augusta and Columbus on his march through Georgia, November-December 1864, but Federal cavalry laid waste to Columbus on April 16, 1865. When Union troops seized Dillard’s depot, it had 4,500 suits of Confederate uniform; 5,890 yards of army jeans; 1,000 yards osnaburgs; 8,820 pairs of shoes; 4,750 pairs of cotton drawers; 1,700 gray jackets; 4,700 pairs of pants; 2,000 pairs of socks; 400 shirts; and, 650 gray caps. This inventory provides a glimpse of what Dillard issued to the Confederate army. The Federals burned Dillard’s manufacturing depot, the Eagle Factory, as well as four cotton factories, a sock factory, a shoe factory, and two other oil cloth factories (besides the Eagle Factory). Again, the list of destruction offers insights into what the manufacturing complex was making for the quartermaster department.[133]

Augusta was the third of Georgia’s three large manufacturing complexes. It bears mentioning that although Augusta is geographically part of Georgia, it generally supplied the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida: the region along these states’ Atlantic coast. Major Isaac T. Winnemore managed the Confederate depot there, having moved from New Orleans when the city fell in April 1862.[134] It was not until October 1862, however, that the depot began full-fledged manufacturing. In that month, Major Lemuel O. Bridewell was assigned there to establish a clothing depot. Bridewell manufactured the first soldier suits of jackets and pants from 23,000 yards of captured Kentucky jeans that General Braxton Bragg had sent to Augusta the same month that Bridewell arrived. Bragg had seized 150,000 yards of jeans and linseys during the Kentucky campaign from Oldham Scott & Company, Lexington, Kentucky. By December 2, 1862, Bridewell had manufactured approximately five thousand soldier suits out of the Kentucky jeans for Bragg’s army.[135] By December, the new clothing factory was busily engaged in making coats and pants (planning to expand the line to shirts and drawers soon thereafter), and furnished employment to numerous cutters and needlewomen.[136]

Details of the Augusta Depot’s clothing are sparse, but some conclusions might be drawn from the materials that Bridewell used. During the second quarter of 1863, Bridewell accounted for the following clothing (both expenditures and remaining stock on hand): 22,307 pair pants; 43,929 shirts; 16,444 coats; 44,939 pair drawers. Likewise, he accounted for the materials that he used in manufacturing his clothing. The following are the chief items in the inventory, the sum of both expenditures and remaining stock on hand. Bridewell’s button stocks included 885 1/3 gross of coat buttons [127,488 or enough for 21,248 six-button jackets]; 3,574 7/12 gross of pant buttons [514,740 or enough for 46,795 pair pants @ 11 buttons per]; 7,357 gross of agate buttons [1,059,408, for shirts and possibly drawers]; 600 gross of jacket buttons [86,400 or enough for 14,400 six-button jackets]; 85 gross of S.C. buttons [South Carolina?], 12,240 or enough for 2,040 six-button jackets]; 11 2/3 dozen brass buttons; and, 227 gross of pant buckles [32,688]. His cloth inventory included 23,340 ¼ yards of wool jeans (and other types); 49,439 7/8 yards of plain kersey; 76,421 7/8 yards of osnaburgs; 56,409 yards of drillings; 190,414 yards of 7/8 width shirtings; 5,400 yards of 3/4 width shirtings; 6,650 yards of red and blue flannel; 336 yards of bunting; 49,689 yards of hickory stripes; 1,118 ¾ yards of cottonade; 8,034 7/8 yards of assorted gray cloth.[137]

Following the Atlanta Campaign, Augusta supplied Hood’s army with clothing since the Army of Tennessee was cut off from Columbus, Georgia. During October and November 1864, the Augusta quartermaster supplied Hood’s army with an estimated 48,408 jackets; 58,305 pairs of pants; 63,356 pairs of shoes; 37,910 shirts; 41,561 pairs of drawers; 60,800 pairs of socks; and, a supply of blankets. This quantity of clothing reflects the scope of the Augusta’s clothing operation, although part of this inventory may have included stocks transferred from Atlanta to Augusta that summer.[138] The Augusta Depot was co-located with several vital factories, as well. Adam Johnson’s Richmond factory manufactured cloth in 1861 “of a cotton and wool mixture” for winter uniforms. Johnson sold these goods to the Richmond, Virginia clothing bureau that year.[139] In August 1862, William E. Jackson’s Augusta factory was an important supplier of cotton goods to both the Atlanta and Richmond Depots, providing sheeting, brown drills, osnaburgs, muslin and shirting (the last for shirts and sand bags).[140] In August 1864, the Augusta factory was the largest supplier of cottons to the Richmond Clothing Bureau, and by May 1864, the Augusta factory provided Cunningham at the Atlanta Depot with half of his cotton goods.[141] Bridges & Ausley of Augusta, established in 1863, was one of the three main Confederate sock factories by the end of the war. Bridges and Ausley furnished Confederate quartermaster with an estimated 240,000 pairs of socks annually.[142] Not only was Augusta a major industrial center, it was one of the only two places in the state still manufacturing clothing by November 1864, (the other being Columbus).[143]

The total quartermaster “field” issues for the Army of Tennessee from July 1, 1864 to January 1, 1865, as reported by the Quartermaster General, were substantial, and did not include issues to men in hospitals, on furlough, detailed at the posts, to officers, or to men who were paroled, exchanged or retired. These issues were made chiefly from the three large Georgia depots: Atlanta, Columbus and Augusta, amounting to: 45,412 jackets; 102,864: pairs of pants; 102,558 pairs of shoes; 27,900 blankets; 61,860 cotton shirts; 45,853 hats and caps; 108,937 pairs of drawers; and, 55,560 pairs of socks.[144]

Smaller operations also made important contributions. John S. Linton’s Athens factory was “engaged in making cloth, for the Georgia companies, on the coast,” (among these General Alexander Lawton’s troops) in 1861. Once Linton fulfilled his obligations to provide Georgia troops with cloth in January 1862, he offered to furnish the Confederate quartermaster with cloth. On 7 June 1861, the Athens factory had also offered to furnish from one to five thousand [soldier] suits.[145] The Athens mill was still selling the Confederate quartermaster woolens in 1864, having furnished 12,958 yards in the six-month period ending in May.[146] This evidence suggests that Linton may have provided modest quantities of uniforms and woolens throughout the war. The firm at Dalton, Georgia, Rinker & Saum, also sold clothing to the quartermaster. On December 20, 1862, they sold 503 jeans jackets (at prices ranging between $14.00, $14.50 and $15.00 each); 778 jeans pants (at various prices including $12.00, $12.50 and $13.00); and, 25 jeans coats at $18.00 each. The varying prices of the jackets and pants suggests differences in quality or materials, or even trim or button type.[147] There was another small clothing manufacturing depot in Macon.[148] The modest production of the State of Florida also added to the overall supply. Florida may have had only one significant cloth mill: William Bailey’s Monticello factory that was in operation during June 1864. Bailey sold his woolens, and much of his osnaburgs, to the State of Florida to clothe Florida troops in Confederate service. Some uniforms may have been manufactured in Florida, as well, as the Richmond Enquirer reported on November 28, 1862, that the trains took two weeks to move thirteen boxes of clothing and shoes from Florida to Dalton, Georgia.[149]

The final element in Georgia’s clothing operation was the Georgia State quartermaster operation. This included the Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau, and the Georgia Relief and Hospital Association. The state quartermaster established the Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau in October 1862 in Augusta. By the winter of 1862-63, the Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau was making 500 garments a day. This clothing was inspected, and if accepted, it was marked with an ink-stamp, “Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau, Augusta, Ga.” Accepted garments were then boxed and sent to Georgia troops in either the Confederate or the state service. From October 1862 through September 15, 1863, the bureau produced 55,000 pairs of pants, 37,000 jackets, 65,000 pairs of drawers, and 70,000 shirts. Its field issues during 1863 included 5,838 hats, 43,728 jackets, 46,325 pants, 32,181 shirts, 30,068 drawers, 23,756 pairs of shoes, and 4,473 pair socks. In November 1863, the bureau had on hand 4,719 hats, 7,291 jackets, 8,828 pants, 9,185 shirts, 8,036 drawers, 12,293 pairs of shoes, and 7,517 pair socks.[150] The Quartermaster General of Georgia, Ira R. Foster, reported on January 30, 1864 that the State of Georgia had issued to Georgia troops in Confederate service (all armies), “about 15,000 suits clothing and about 30,000 pair of shoes” during that winter. These had been either manufactured by or contracted for by the state.[151] One can infer that the balance of the clothing not furnished to Georgia troops in Confederate service went to state militia troops, detailed soldiers, troops in hospitals and the like. Confederate Quartermaster General, A.R. Lawton, also noted the State of Georgia’s contributions to troops in Confederate service for the year of 1864. These included 26,745 jackets, 28,808 pairs of pants, 37,657 pairs of shoes, 7,504 blankets, 24,952 shirts, 24,168 pairs of drawers, and, 23,024 pairs of socks.[152] Part of this was a consignment of 3,000 uniforms of “Joe Brown Clothes” sent to the Georgia brigades of Longstreet’s Corps at Morristown, Tennessee in March 1864. These uniforms were described being a “dingie white” color. In the Spring of 1864, the bureau sent between 5,000 and 7,000 uniforms to the Army of Tennessee.[153] Overall, the Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau made substantial contributions of clothing during the war.

The most significant surviving Georgia Soldiers Clothing Bureau (GSCB) artifact is a pair of trousers owned by John McNish Hazlehurst. These pants are ink-stamped with the GSCB’s name which conclusively proves their provenance to the Georgia State quartermaster operation. Hazlehurst was a seventeen-year-old cadet from Georgia Military Institute who fought with the Georgia Battalion of Cadets in the Army of Tennessee from the spring of 1864 until May 1865. Hazlehurst, and perhaps the entire cadet battalion, appears to have been issued Georgia State clothing during his active service. The pants themselves are made from coarse, plain woven fabric. The warp is a heavy cotton yarn, natural white in color, and the weft is a warm, medium brown wool yarn. The wool appears to have been either dyed brown or spun from brown colored wool fibers. The white and brown yarns together give the fabric an overall light brown color. The pants have side seam pockets, a five-button fly, and six suspender buttons at the waistband. All the trouser buttons match: natural-white bone buttons. The adjustment belt under the rear waist seam has the buckle component on the left (a brass swivel buckle), and the tongue on the right. The lining pieces are made entirely of osnaburgs, and the ink stamp is positioned on the left pocket bag: “GEORGIA SOLDIERS CLOTHING BUREAU AUGUSTA G.”[154]

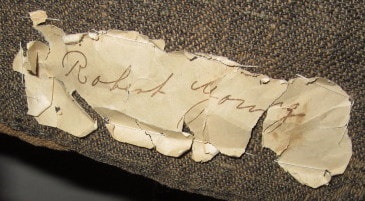

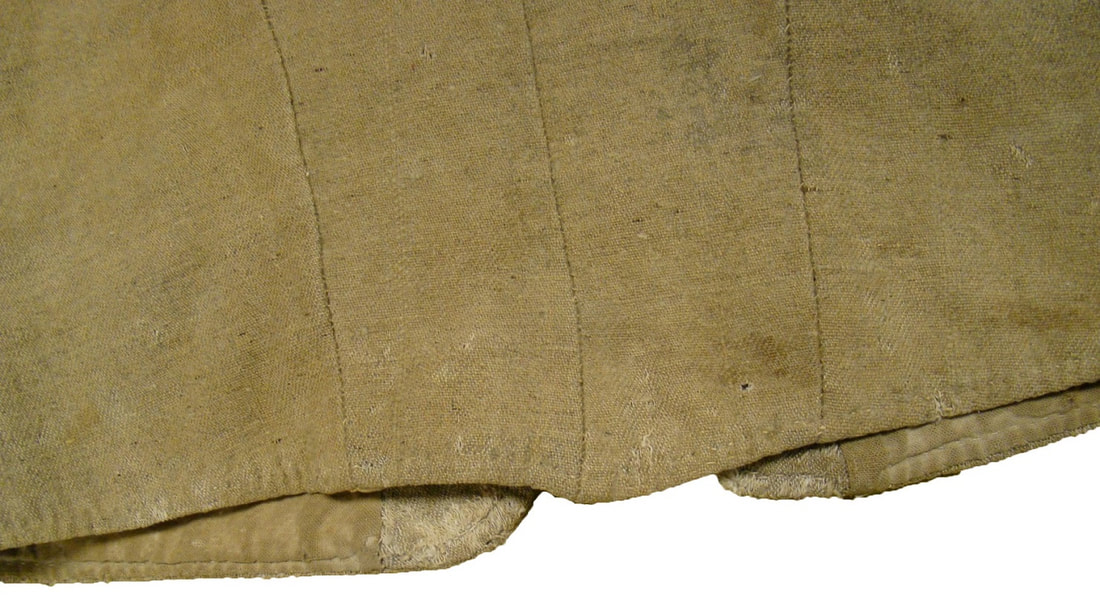

A jacket belonging to Robert Young of the 12th Georgia Infantry is thought to be a Georgia state issue jacket. Young’s regiment served in the Army of Northern Virginia. The jacket has an eight-button front, and the remaining buttons are Georgia state seal buttons. The basic cloth is steel-gray colored jeans. The jacket has a six-piece body, one-piece sleeves and a two-piece collar. The lining has a one-piece back and one-piece side-front pieces. The lapel facings are very wide and connect to the back piece over the armholes. The sleeve and side lining pieces are of fine woven, natural tan colored osnaburg. The back piece is a coarser woven, natural tannish-white osnaburg. There are inset pockets in either side of the chest lining, with the openings cut partially through the lapel facings. These openings have jeans fabric welts. The jacket is without topstitching. Young’s jacket may represent one of many patterns used to make Georgia state jackets.[155]

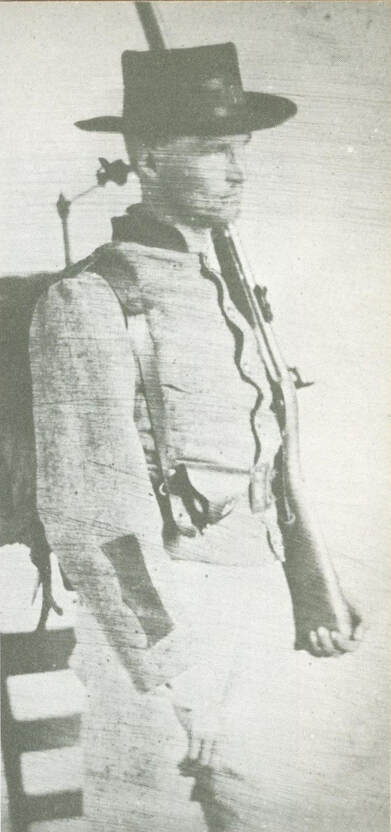

At least one image survives of a soldier wearing what is believed to be a Georgia Soldier’s Clothing Bureau uniform. The image shows Ivey W. Duggan wearing a pair of white pants and contrasting-colored jacket. The six-button jacket may have been light gray. The jacket features black facings: collar, shoulder straps, vertical cuff flashings. The jacket’s right front exhibits a chest pocket with a scalloped flap. Duggan served from 1861 to 1865 in the Army of Northern Virginia. He first served as a private in Company K, 15th Georgia Infantry, and in October 1862 he was transferred to the 49th Georgia Infantry where he served as a quartermaster sergeant. Since his jacket has no chevrons, the image may date to his service with the 15th Georgia. As with Young’s jacket, Duggan’s uniform may represent just one of many variants of Georgia state-issue uniforms.[156]

The Georgia Relief and Hospital Association (GR&HA) provided significant amounts of clothing to Georgia soldiers, distributing it at hospitals. The GR&HA operated a clothing manufacturing depot in Augusta with a foreman-cutter and two assistant cutters. It had an issuing depot in Richmond, Virginia, where most of its production was sent for distribution. The GR&HA reported for the period of October 20, 1862 to October 10, 1863 the following statistics. Its clothing operation started the period with the following stock on hand: 29 coats, 224 pairs of pants, 746 shirts, 579 pairs of drawers, 363 pairs of socks and no pairs of shoes. The GR&HA manufactured or purchased 4,952 coats, 12,217 pairs of pants, 22,938 shirts, 18,682 pairs of drawers, 5,641 pairs of socks and 6,939 pairs of shoes. It received contributions of 483 coats, 1,727 pairs of pants, 814 shirts, 991 pairs of drawers, 2,845 pairs of socks and 394 pairs of shoes. During that year it distributed 4,492 coats (3,476 to Richmond), 10,183 pairs of pants (7,344 to Richmond), 19,320 shirts (11,182 to Richmond), 18,457 pairs of drawers (11,524 to Richmond), 7,556 pairs of socks (4,755 to Richmond) and 5,589 pairs of shoes (3,667 to Richmond). The GR&HA ended the reporting period with the remaining stock on hand: 972 coats, 3,985 pairs of pants, 5,178 shirts, 1,795 pairs of drawers, 1,293 pairs of socks and 1,744 pairs of shoes. The prices for each article were as follows: coats $15.00, pants $12.00, shirts $3.00, drawers $2.25, socks per pair $0.75 and shoes per pair $12.00. The association used jeans as the basic coat and pants material, shirtings for making shirts, and both shirtings and osnaburgs for making drawers. In addition to the clothing, the GR&HA distributed blankets, quilts and comforters, and sheets. While Georgia soldiers in Richmond hospitals received roughly two-thirds of this bounty, other hospitals in Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, the Carolinas, and Georgia received modest amounts, as well.[157]

One example of fully provenanced clothing survives from the Georgia Relief & Hospital Association. This is the pair of trousers that belonged to Lieutenant Hamilton Branch. As with Hazlehurst’s Georgia Soldiers Clothing Bureau trousers, Branch’s trousers have an ink stamp on the left pocket bag: “GEO. RELF. & HOSP. ASS.” Branch served with the 54th Georgia Infantry and was wounded during the Atlanta Campaign in July 1864. He spent some months recuperating in Savannah and may have acquired these trousers while in the hospital. Branch’s pants are made from jeans with a natural white cotton warp and a natural white woolen weft. The weave’s warp yarn passes over one and under two weft yarns, and the weft yarn goes over two and under one warp yarn. The pants have side seam pockets and separate yoke pieces between the waist band and the rear leg pieces. The pants do not appear the have been made with an adjusting belt at the rear waist seam, nor any suspender buttons. The buttons on the fly are an assortment of different bone buttons. The waistband button is attached to the inside of the left waistband, so that it buttons to the inside and is hidden from view. All the linings are of unbleached osnaburg. A complete range of images for this artifact is available in the article, “The South’s White Uniforms.”[158]

One example of fully provenanced clothing survives from the Georgia Relief & Hospital Association. This is the pair of trousers that belonged to Lieutenant Hamilton Branch. As with Hazlehurst’s Georgia Soldiers Clothing Bureau trousers, Branch’s trousers have an ink stamp on the left pocket bag: “GEO. RELF. & HOSP. ASS.” Branch served with the 54th Georgia Infantry and was wounded during the Atlanta Campaign in July 1864. He spent some months recuperating in Savannah and may have acquired these trousers while in the hospital. Branch’s pants are made from jeans with a natural white cotton warp and a natural white woolen weft. The weave’s warp yarn passes over one and under two weft yarns, and the weft yarn goes over two and under one warp yarn. The pants have side seam pockets and separate yoke pieces between the waist band and the rear leg pieces. The pants do not appear the have been made with an adjusting belt at the rear waist seam, nor any suspender buttons. The buttons on the fly are an assortment of different bone buttons. The waistband button is attached to the inside of the left waistband, so that it buttons to the inside and is hidden from view. All the linings are of unbleached osnaburg. A complete range of images for this artifact is available in the article, “The South’s White Uniforms.”[158]

Remarkably, two other pairs of pants with provenance to Georgia are nearly identical to the GR&HA trousers. These include a second pair of pants owned by Hamilton Branch and a pair owned by South Carolina soldier, Samuel Powell Cooper. Both these pairs of trousers may have been issued by the GR&HA. Branch’s trousers are made from a steel gray colored jeans cloth. The gray fabric is somewhat more finely woven that that of the white pair previously described. The adjustment belt is completely intact and has a rusty iron buckle with traces of japanning on the surface. The trousers have the same type of side seam front pockets, separate yoke pieces in the rear and the rear seam is sewn entirely closed to the top of the waistband. The pants are completely lined with woolen cloth, possibly having been done when they were made.[159]

Samuel Powell Cooper’s trousers closely match both of Branch’s pairs of trousers. Cooper was in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry. This regiment served in the Army of Northern Virginia from March 1864 until transferring to the Army of Tennessee for the Carolina Campaign. He presumably acquired the pants in the last months of the war, quite possibly from the GR&HA, even though he was a South Carolinian. Cooper’s trousers are made of tan-colored jeans. The pants have side seam opening pockets, and the fly closes with five buttons: one at the waistband and the other four on the bottom fly piece. Only one wooden button remains on the pants, at the fly. The rear of the pants have the same type of separate yoke pieces observed in the Branch trousers, but the adjustment belt is missing (assuming it had one to start with). The rear waistband seam is also closed all the way up, omitting the usual notch, and the pants are lined with unbleached osnaburg.[160] Only the GR&HA ink stamp is missing from Cooper’s pants.

Samuel Powell Cooper’s trousers closely match both of Branch’s pairs of trousers. Cooper was in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry. This regiment served in the Army of Northern Virginia from March 1864 until transferring to the Army of Tennessee for the Carolina Campaign. He presumably acquired the pants in the last months of the war, quite possibly from the GR&HA, even though he was a South Carolinian. Cooper’s trousers are made of tan-colored jeans. The pants have side seam opening pockets, and the fly closes with five buttons: one at the waistband and the other four on the bottom fly piece. Only one wooden button remains on the pants, at the fly. The rear of the pants have the same type of separate yoke pieces observed in the Branch trousers, but the adjustment belt is missing (assuming it had one to start with). The rear waistband seam is also closed all the way up, omitting the usual notch, and the pants are lined with unbleached osnaburg.[160] Only the GR&HA ink stamp is missing from Cooper’s pants.

The pants of Jesse Bryant Beck, Company A, 25th Alabama Infantry, have provenance to the Georgia region, as well, but are cut differently than those of the GR&HA. According to Beck’s grandson, who donated the pants to the Museum of the Confederacy, Jesse Beck wore the pants while he was wounded in the leg in July 1864 during the Atlanta Campaign. This suggests that Beck got his trousers as part of the Army of Tennessee shortly before being wounded in July 1864, and that the trousers are likely a product of the Columbus-Atlanta clothing operation. Little is known of Beck’s service after the Atlanta Campaign except that he was in the Way Hospital, Meridian, Mississippi in January 1865. A bullet, or shrapnel hole is present in the lower left pants leg, and the pants are clean, indicating that Beck wore them when he was wounded and that they were thoroughly washed at some point afterwards.[161]

The pants are made of a coarse jeans fabric. The weave’s warp yarn passes over one and under two weft yarns, and the weft yarn goes over two and under one warp yarn. Both the cotton warp and the woolen weft are a natural white color, giving the pants an overall natural white color. The pants have “V” opening pockets, a five-button fly and six suspender buttons. The buttons are all white bone except for one replacement: a white glass button. The rear panels have darts sewn into the tops at the waistband seam, between the side seams and the belt components. The adjustment belt is missing the buckle, but the rust stains on both components reveal that an iron buckle was sewn to the left piece and secured to the tongue on the right side. The pants are lined with unbleached osnaburg.[162]

The pants are made of a coarse jeans fabric. The weave’s warp yarn passes over one and under two weft yarns, and the weft yarn goes over two and under one warp yarn. Both the cotton warp and the woolen weft are a natural white color, giving the pants an overall natural white color. The pants have “V” opening pockets, a five-button fly and six suspender buttons. The buttons are all white bone except for one replacement: a white glass button. The rear panels have darts sewn into the tops at the waistband seam, between the side seams and the belt components. The adjustment belt is missing the buckle, but the rust stains on both components reveal that an iron buckle was sewn to the left piece and secured to the tongue on the right side. The pants are lined with unbleached osnaburg.[162]

When considering the numerous, indifferent surviving jackets with a Georgia provenance, we cannot state definitively which quartermaster operation made them, but they all appear to be mass-produced, government clothing. A white jacket that was taken as a souvenir during the Atlanta campaign by an Iowa soldier is one of these. Its provenance puts the jacket in the Atlanta area during the summer of 1864.[163] The jacket is missing its buttons, but there are six remaining buttonholes. The jacket appears to have been made with seven buttonholes, but the lower lapels have been modified to curve them and remove the bottom buttonhole and button. It is difficult to say whether this was intentional, or due to the lapel bottoms having frayed and been removed as a repair. The jacket’s basic fabric is a woolen-cotton tabby weave with a white cotton warp and an undyed, natural white woolen weft. The lining is unbleached osnaburg. The jacket has one-piece sleeves, a one-piece collar, and a four-piece body (the side pieces being omitted). The lining pattern corresponds to the basic fabric, excepting the lapel facings. There is one huge interior patch pocket on the left, front panel.

Another white woolen jacket with provenance to 1864 belonged to John Britten Lewis Grizzard, Hanleiter’s Company, Georgia Light Artillery, 38th Georgia Volunteers, Battery B. Grizzard served in Charleston and Savannah. Grizzard joined the Confederate army in Atlanta on February 3, 1864. He served at least through October 1864, at which point no further service records are available. He received a clothing issue on February 22, 1864. He died two years after the war, and was buried at Union City, Georgia. By the time Grizzard joined the battery, it was serving at Beaulieu, Georgia, about twelve miles below Savannah. It retreated from there with the Confederate army on December 20, 1864 to Charleston. From there, it participated with the army in the Carolina campaign, finally surrendering with Johnston’s Army at Greensboro, North Carolina, on April 26, 1865.[164] Regarding the jacket’s provenance, it may have been issued in Atlanta as early as February 1864, but may also have been issued in Savannah, Charleston or during the Carolina Campaign. It could have come from any of the numerous small factories in Georgia or the Carolinas. In any case, the undyed, natural white color corresponds to much of the clothing with provenance to the region.

Regarding the jacket itself, it a simple, natural white-colored roundabout, with a five-button front, and an outside, left breast pocket. All the jacket's original, brass dome buttons are intact. The basic fabric is a two-over-one jeans weave, natural white cotton warp and a natural white, undyed woolen weft. Several patches of the original wool nap remain intact, and suggest that the wool was indeed never dyed, being a natural white color when the jacket was made. The jacket has a six-piece body, two-piece sleeves, and is entirely hand sewn. The body lining is made of unbleached white osnaburg, and the sleeves are made from polished cotton. The front lapel facings are top back-stitched; the bottom edge and collar have a basting stitch; and, the cuffs have no top stitching. There is an additional pocket on the inside right breast, that appears to have been added post-manufacture, as it is of a coarser osnaburg than the rest of the lining and is whipstitched in place.[165]

Regarding the jacket itself, it a simple, natural white-colored roundabout, with a five-button front, and an outside, left breast pocket. All the jacket's original, brass dome buttons are intact. The basic fabric is a two-over-one jeans weave, natural white cotton warp and a natural white, undyed woolen weft. Several patches of the original wool nap remain intact, and suggest that the wool was indeed never dyed, being a natural white color when the jacket was made. The jacket has a six-piece body, two-piece sleeves, and is entirely hand sewn. The body lining is made of unbleached white osnaburg, and the sleeves are made from polished cotton. The front lapel facings are top back-stitched; the bottom edge and collar have a basting stitch; and, the cuffs have no top stitching. There is an additional pocket on the inside right breast, that appears to have been added post-manufacture, as it is of a coarser osnaburg than the rest of the lining and is whipstitched in place.[165]

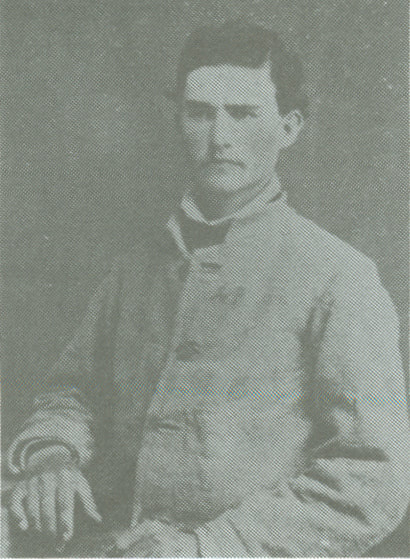

An example of a very late war jacket is that worn by John C. Zehring, Company A, 4th Tennessee Infantry. Judging from the jacket’s good condition, Zehring probably drew it during the last months of the war in Milledgeville, where he served as a hospital steward, and wore it until the end of the war. Some have speculated that the jacket was made at the small factory: the Milledgeville Manufacturing Company. This is difficult to prove since the jacket might have come from any of the small uniform suppliers in the region. In any case, the jacket is very plain, being devoid of any trim, and made of coarse, butternut-colored jeans with six front buttons. The jacket has one-piece sleeves, a six-piece body and a two-piece collar. The extant buttons are cuff-sized, Federal staff buttons. The lining is unbleached osnaburg. Zehring penned his name and organization in the lining, “JOHN C. ZEHRING CO. A SHELBY GRAYS 4TH TENN. REG'T C.S.A.”.[166]

Perhaps the latest documented, Georgia-issued jacket is the Clark N. Thorp jacket. This jacket has a fascinating story. A Federal prisoner-of-war from Andersonville brought it home when he was released from that prison on April 20, 1865. Accordingly, a Confederate private at Andersonville gave his new, Confederate jacket to Thorp in exchange for Thorp’s ragged Federal blouse. Thorp had been captured at Chickamauga and his organization was Company B, 19th US Infantry Regiment. He kept the Confederate jacket as a souvenir for the rest of his life. 57b.

The Thorp jacket presumably came from a Lower South factory in Georgia. The following assessment is somewhat tentative based on the low resolution of the images available. That said, the basic fabric is a light weight, woolen-cotton, tabby-weave. The fabric appears to be undyed, natural white. The jacket is lined with unbleached osnaburg. It has two-piece sleeves, a two-piece collar, and an undetermined cut to the body (the image renders this inconclusive). It also has a slanted, exterior, left breast pocket. The jacket closes with a four-button front. The buttons are all intact: four-hole, hard rubber.[167] The jacket is unusual, having only four buttons, and it is worth mentioning that this reflects a general trend to reduce the number of buttons on Confederate jackets over the course of the war. Remarkably, an image of a soldier survives with just such a jacket. This was of Private Joseph Parker, Company D, 57th Alabama Infantry. Parker was at his home in Ozark, Alabama at the time of the surrender, recovering from wounds received at the Battle of Franklin. He may have received the jacket at the hospital or while recuperating in early 1865. Ozark is only 117 miles from Andersonville, so there is a good chance that the Thorp and Parker jackets were made by the same manufacturer and issued in the same area.[168]

The Thorp jacket presumably came from a Lower South factory in Georgia. The following assessment is somewhat tentative based on the low resolution of the images available. That said, the basic fabric is a light weight, woolen-cotton, tabby-weave. The fabric appears to be undyed, natural white. The jacket is lined with unbleached osnaburg. It has two-piece sleeves, a two-piece collar, and an undetermined cut to the body (the image renders this inconclusive). It also has a slanted, exterior, left breast pocket. The jacket closes with a four-button front. The buttons are all intact: four-hole, hard rubber.[167] The jacket is unusual, having only four buttons, and it is worth mentioning that this reflects a general trend to reduce the number of buttons on Confederate jackets over the course of the war. Remarkably, an image of a soldier survives with just such a jacket. This was of Private Joseph Parker, Company D, 57th Alabama Infantry. Parker was at his home in Ozark, Alabama at the time of the surrender, recovering from wounds received at the Battle of Franklin. He may have received the jacket at the hospital or while recuperating in early 1865. Ozark is only 117 miles from Andersonville, so there is a good chance that the Thorp and Parker jackets were made by the same manufacturer and issued in the same area.[168]

Another simple, butternut jacket is one attributed to Dewitt C. Gallaher, Company E, 1st Virginia Cavalry. Although it was used by a Virginia Army soldier, the jacket was probably supplied from a Lower South factory, as Lee’s army received significant supplies from Georgia shops. The tailoring of Gallaher’s jacket is distinctly different from the patterns of the Richmond, Southwest Virginia or North Carolina depots. This may indicate that Gallaher’s jacket came from a point further south.

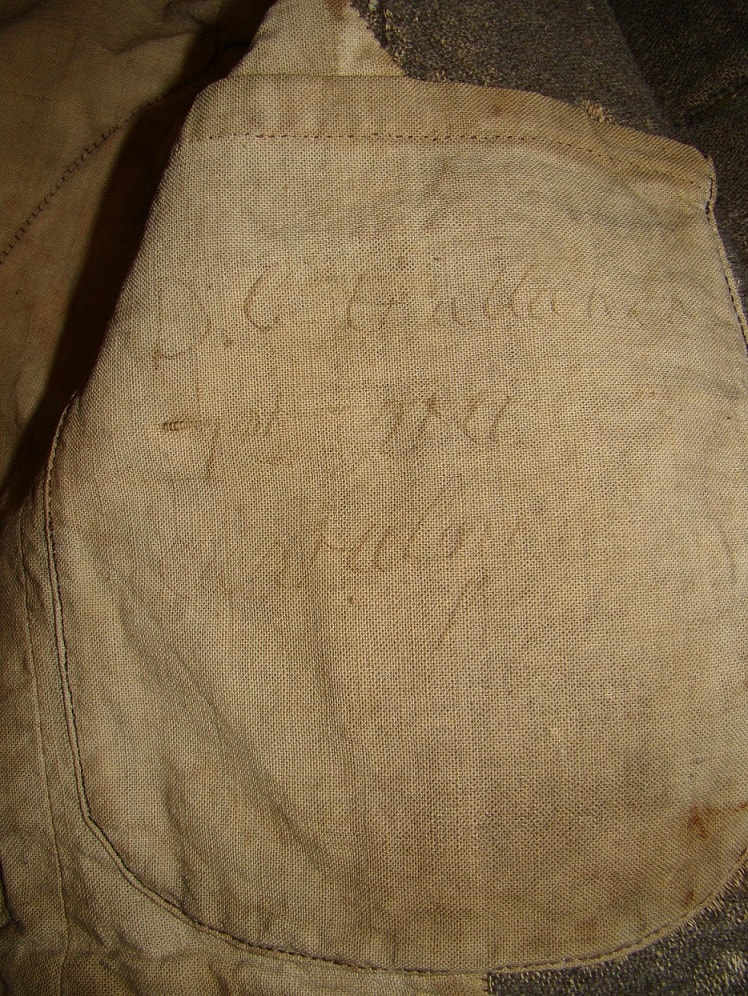

Gallaher’s jacket is similar to the Richmond Depot pattern, except that it has one-piece sleeves, and only seven front buttons. The unbleached osnaburg lining differs significantly from the Richmond pattern with interior patch pockets and wide lapel facings that arc over the armholes to join the back seam. Each lapel facing is pieced together from two separate pieces. The basic fabric is woolen-cotton jeans of a warm, medium brown color. The jacket has a six-piece body and a two-piece collar, the buttons are Federal staff pattern, and there is topstitching all around the jacket edge. Gallaher’s name and command are penned in lining.[169]

Gallaher’s jacket is similar to the Richmond Depot pattern, except that it has one-piece sleeves, and only seven front buttons. The unbleached osnaburg lining differs significantly from the Richmond pattern with interior patch pockets and wide lapel facings that arc over the armholes to join the back seam. Each lapel facing is pieced together from two separate pieces. The basic fabric is woolen-cotton jeans of a warm, medium brown color. The jacket has a six-piece body and a two-piece collar, the buttons are Federal staff pattern, and there is topstitching all around the jacket edge. Gallaher’s name and command are penned in lining.[169]

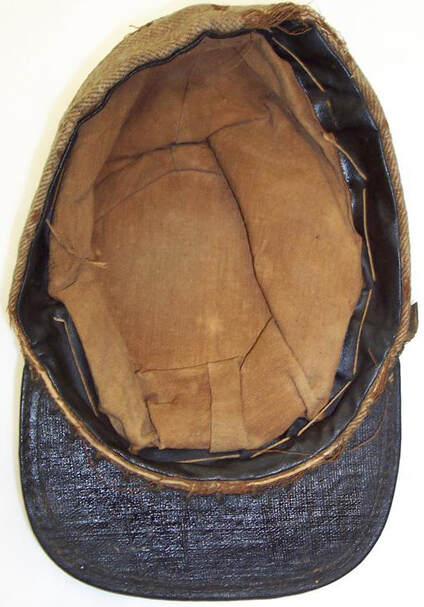

Caps with provenance to the Georgia region and Army of Tennessee include the Sykes, Inabinet and Bowman caps (that are all the same pattern), the Anderson cap and a low crowned forage cap.

The first three caps may have been made by the Columbus-Atlanta depot operation, judging from the basic twill-weave fabric, which is a perfect match for most of the Columbus-Atlanta jackets. All three have clear provenance to the Western theater. The most salient feature of these caps is the omission of band at the base. Instead of the usual band, the sides form the base at the bottom of the cap as seen in the Federal forage cap. Sykes’ cap was in his possession in January 1865 when he met a tragic death in Tupelo, Mississippi following the Tennessee Campaign. While sleeping under a tree, the tree toppled on him and killed him. Lieutenant Colonel Columbus Sykes served with the 43rd Mississippi Infantry. Interestingly, the buttons on Sykes’ cap appear to be two-hole, leather buttons.[170] The cap owned by First Sergeant David Jacob Inabinet is identical to Sykes’ cap except that the buttons are four-hole, white bone buttons covered with black cloth. Inabinet’s regiment, the 20th South Carolina Infantry served in the Army of Northern Virginia for the last year of the war (when Inabinet would have presumably obtained it). Nevertheless, Inabinet was sent home to Orangeburg, South Carolina on convalescence furlough on August 31, 1864 for an unstated period. It is possible that he drew the cap while on furlough from stocks that came from the Columbus-Atlanta operation.[171] The last of this type is the Bowman cap. All that is known about Private Cicero Bowman is that he served in Company A, 5th Georgia Reserves during April and May 1863. His company was part of Captain C.D. Findlay’s Ordnance Guard at Macon, Georgia. He would have received his cap while serving there. Bowman’s cap differs from the other two only in that it has the remnants of a red band sewn around its base. Findlay’s Company probably drew red-trimmed caps to indicate their affiliation with the ordnance branch. In any case, Bowman’s cap represents a trimmed variant of the “Columbus-Atlanta” cap and suggests that the operation made more caps with colored blue and red bands, as well.[172]

The first three caps may have been made by the Columbus-Atlanta depot operation, judging from the basic twill-weave fabric, which is a perfect match for most of the Columbus-Atlanta jackets. All three have clear provenance to the Western theater. The most salient feature of these caps is the omission of band at the base. Instead of the usual band, the sides form the base at the bottom of the cap as seen in the Federal forage cap. Sykes’ cap was in his possession in January 1865 when he met a tragic death in Tupelo, Mississippi following the Tennessee Campaign. While sleeping under a tree, the tree toppled on him and killed him. Lieutenant Colonel Columbus Sykes served with the 43rd Mississippi Infantry. Interestingly, the buttons on Sykes’ cap appear to be two-hole, leather buttons.[170] The cap owned by First Sergeant David Jacob Inabinet is identical to Sykes’ cap except that the buttons are four-hole, white bone buttons covered with black cloth. Inabinet’s regiment, the 20th South Carolina Infantry served in the Army of Northern Virginia for the last year of the war (when Inabinet would have presumably obtained it). Nevertheless, Inabinet was sent home to Orangeburg, South Carolina on convalescence furlough on August 31, 1864 for an unstated period. It is possible that he drew the cap while on furlough from stocks that came from the Columbus-Atlanta operation.[171] The last of this type is the Bowman cap. All that is known about Private Cicero Bowman is that he served in Company A, 5th Georgia Reserves during April and May 1863. His company was part of Captain C.D. Findlay’s Ordnance Guard at Macon, Georgia. He would have received his cap while serving there. Bowman’s cap differs from the other two only in that it has the remnants of a red band sewn around its base. Findlay’s Company probably drew red-trimmed caps to indicate their affiliation with the ordnance branch. In any case, Bowman’s cap represents a trimmed variant of the “Columbus-Atlanta” cap and suggests that the operation made more caps with colored blue and red bands, as well.[172]

The next surviving cap from the region was worn by Color Sergeant Robert C. Anderson, 2nd Kentucky Infantry, CSA. Anderson was wearing this cap when he was killed at the Chickamauga, while fighting with the Army of Tennessee. The Anderson cap is made from a plain-woven fabric with a very heavy nap. The warp is a tannish-yellow cotton and the weft a whitish woolen. Interestingly, the largely intact, thick nap is a light steel gray color. This color remains constant inside and out, and under the seams, all these areas being exposed since the cap has no interior lining on the sides. There is no indication that the cap faded from another shade. The pasteboard visor is unusual, having a leather top, enameled cloth bottom and a welt around the outer edge made of black cotton tape (whipstitched in place rather than machine sewn). The pasteboard crown has a layer of buckram or jeans cloth between it and the basic cloth on top. It had no lining inside the crown, but Anderson apparently added a piece of blue cloth to that surface himself. The sweatband and chinstrap are enameled cloth, and there is no buckram stiffening between the sweatband and outer cloth band. The band is two-piece having a front as well as a rear seam, and the cap appears to be machine-stitched. The one surviving button is a Federal general service button. The Anderson cap is unlike any other surviving Confederate cap and may be the product of a small factory with a limited output.[173]

A final cap without provenance may have been used in the Western theater and is a low-sided forage cap. It is identified only by the name of its collection: the Cunningham cap. The cap is distinct from the typical chasseur pattern used for most Confederate caps, having omitted the countersunk crown. The crown is made in the Federal army forage cap style with a reinforced welt underneath that prevents it from caving inwards. Otherwise, the Cunningham cap follows the pattern of typical Confederate caps having a separate band and the visor attached through the front of the band. The basic cloth of the sides and crown is a light steel-gray colored twill with a very heavy nap that easily conceals the warp. The weave’s weft goes over two and under two warp yarns and the warp goes over one and under two weft yarns. The thick weft yarn is light gray and heavy, coarse a warp yarn is a natural white. The band is a light weight, black woolen flannel. The chinstrap and visor are leather, the visor made from two layers of very thin leather that have been glued together and machine-sewn around the outer edge without a welt. The sweatband is enameled cloth and the lining a fine white, polished cotton. The band appears to be stiffened with pasteboard or leather, and the chinstrap is secured with four-hole, white bone buttons.[174]

63a. The 63-series of artifact is courtesy of Dr. Michael R. Cunningham. While this cap is without provenance, there is another nearly identical, surviving Confederate cap in the Gettysburg National Battlefield Park collection (allegedly recovered from that battlefield as a souvenir). Furthermore, there is an image of a fallen Confederate at Antietam with this type of cap. It seems to have been used by the Virginia Army, but may have been made in the Lower South.

This image of Confederate dead, who had fallen on September 17, 1862 at the Antietam battlefield, includes one of the low forage caps described herein. The soldier with the Federal sack coat, in the center of the image, has this cap next to his head. The image is courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Click this link to navigate to Part IV of this study...

Acknowledgments:

The institutions, museum professionals and private collectors who have shared artifacts and images used in the third part of this study are listed below. Without their generosity and time, this study would not be complete. These include the Library of Congress; the Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas and CEO Ray Richey; the Mansfield Battlefield state Commemorative Site, Louisiana State Parks and the late Park Manager Steve Bounds; Atlanta History Center, Atlanta, Georgia, Military Historian and Curator, Dr. Gordon L. Jones; the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina and Curators Rachel H. Cockrell and William J. Long; Gettysburg National Park collection, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and Curator Paul Shevchuk; Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park collection, Kennesaw, Georgia and Curator W.R. "Willie" Johnson; the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia and Museum Curator, Robert Hancock; Kentucky Military History Museum, Frankfort, Kentucky; Dr. Michael R. Cunningham, Joe Fitzgerald; Joe Fitzgerald; Gary Hendershott Museum Consultants; Jack W. Melton, Jr.; Mrs. Walter B. Hill; Horse Soldier Military Antiques; Alan T. Parker; Antiques Roadshow; and, other, unnamed private collections.

Copyright: All images in this article are copyrighted to the Adolphus Confederate Uniforms website with the exception of those that are part of the Library of Congress collection.

Bibliography

[122] The artifact used as an example of the Columbus type was worn by James S. Wise, Company G, 41st Georgia Infantry, courtesy of Ray Richey, TCWM, author examined the jacket on 19 February 2018; CSR Georgia, M 266, Roll 454; Leslie D. Jensen first published this jacket as a typology, having been manufactured in Columbus, Georgia in his ground-breaking article, A Survey of Confederate Central Government Quartermaster Issue Jackets, Part II, Military Collector and Historian, Vol. XLI, No. 4, Winter 1989, pp. 162-171, (hereafter, Jensen Survey). Geoffrey R. Walden followed in 1995 with an exhaustive study of the Columbus jacket in his article, Confederate “Columbus Depot” Jackets: The Material Evidence, published in the The Authentic Campaigner website: http://www.authentic-campaigner.com/articles/walden/cdjacket.htm.

[123] Sorrel, G. Moxley, Recollections of a Confederate Staff Officer, Arcadia Ebooks, 1905, Chapter XXVI, Chattanooga – Incidents, page 133, Lieutenant Colonel Gilbert Moxley Sorrel, Longstreet’s staff, commenting on the uniform of the Army of Tennessee, September 1863.

[124] Wilson, p. 82.

[125] Arliskas, p. 40, from Jones and Farris, The Civil War Diary of John Farris, Franklin County Historical Society Review, Vol. XXV, 1994, p. 53, and the Columbus Daily Sun, Georgia, September 16, 1862.

[126] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1889 (also known as the ORs), Series 1, Vol 23, Part 2, Exhibit E, April 4, 1863, Major V.K. Stevenson to Colonel William Preston; see also Arliskas, Chapter 2, Part 3, p. 61, and note 9, p. 101.

[127] Wilson, p. 123.

[128] Wilson, pp. 206, 212-213.

[129] Wilson, pp. xx, 204, 206, & Appendix A.

[130] Wilson, p. 23.

[131] Arliskas, p. 61, Chapter 2, Part 3.

[132] CSA Citizens, Firms, Eagle Manufacturing Company, Roll 270; and Wilson, page 133.

[133] Wilson, p. 222, 234, 248 (from the ORs that provide a full report).

[134] Wilson, p. 34.

[135] Numerous accounts provide fragments of the story about the captured Kentucky cloth and its subsequent use. The Atlanta Intelligencier newspaper, Atlanta, Georgia, February 20, 1863, stated that General Kirby Smith had received 90,000 yards of the largesse, and the other 37,000 yards went to an unspecified recipient. Bragg also brought out about 50,000 yards of flannel and calico, and Kirby Smith brought out 6,000 pair shoes, 3,000 blankets, 2,000 overcoats, and a quantity of shirts, socks and camp equipment. The Weekly Columbus Enquirer newspaper, Georgia, December 2, 1862, p. 3, c. 2, November 27, 1862, reported that Major L.O. Bridewell, of Bragg’s staff, took 23,000 yards of Kentucky jeans to Augusta to have made into uniforms, and that by July 1863, he had had 10,000 uniforms made up. The Charleston Courier reported beforehand that Bridewell had had 5,000 suits made from the Kentucky jeans at the Augusta depot, and that this was “Clothing for the Army of the Mississippi.” (References courtesy of Arliskas, pp. 40-41).

[136] Augusta Chronicle newspaper, from the Rome Tri-Weekly Courier, Georgia, December 18, 1862.

[137] CSR Officers, M331, Roll 33, misfiled under Captain Charles A. Bridewell, includes the records of Major Lemuel O. Bridewell. Crews.

[138] Wilson, p. 127.

[139] Wilson, p. 23.

[140] Wilson, p. 65.

[141] Wilson, p. 207 & Appendix A.

[142] Wilson, pp. 150-151, 160, & 179.

[143] Wilson, pp. 212-213.

[144] Wilson, p. 127.

[145] Wilson, pp. 22, 24.

[146] Wilson, Appendix A.

[147] CSA Citizens, Rinker & Saum, December 25, 1862, Dalton, Georgia, Roll 867.

[148] Arliskas, p. 61, uncited.

[149] Wilson, pp. 83, 114-115.

[150] Arliskas, p. 60, Chapter 2, Part 3, note 2, p. 101.

[151] Wilson, pp. 114-115; Annual report of Ira R. Foster, Quartermaster General, Georgia, for the Fiscal Year ending 15 October 1864, Milledgeville, Georgia (hereafter, Foster, October 1864; reference courtesy of Arliskas, p. 77); Heller, J.R. & C.A., Eds, The Confederacy is on her way up the spout, Letters to South Carolina, 1861-1864, The University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia, 1992, p. 116 (hereafter, Heller; reference courtesy of Lee White); and Arliskas, Chapter 2, Part 8, pp. 74-75, note 4-9, p. 102.

[152] Wilson, p. 127, House of Representatives, February 11, 1865, Report of Special Committee on the Pay and Clothing of the Confederate Army by QM General Lawton.

[153] Foster, October 1864 (reference courtesy of Arliskas, p. 77); Heller (ref courtesy of Lee White); and Arliskas, Chapter 2, Part 8, pp. 74-75, note 4-9, p. 102.

[154] The Hazlehurst pants are courtesy of the Atlanta History Center Collection, Atlanta, Georgia (hereafter, AHC), author examined the pants on 23 April 2013; John McNish Hazlehurst’s service is not in the CSR since he was a Georgia Military Institute cadet.

[155] The Young jacket resides in a private collection; CSR Georgia, M266, Roll 275, the 12th Georgia Infantry had two soldiers with this name: Robert N. Young, Company F and Robert Young, Company G. Both served until the end of the war in the Army of Northern Virginia.

[156] Wiley, Bell Irvin, Embattled Confederates: An Illustrated History of Southerners at War, Bonanza Books, New York, 1964, p. 74, Private Ivey W. Duncan [Duggan], Fifteenth Georgia Infantry, image courtesy of Mrs. Walter B. Hill, Clarksville, Georgia; CSR Georgia, M266, Roll 292, Company K, 15th Georgia Infantry, Ivy W. Duggan.

[157] Report of the Board of Superintendents of the Georgia Relief & Hospital Association to the Governor and General Assembly of Georgia with the Proceedings of the Board, Convened at Augusta, Ga, October 28, 1863, published in Augusta, Georgia by the Steam Press of Constitutionalist, 1863 (and made available in a digital format by the Boston Athenaeum, ca 2017), pp. 8, 16-25, 28.

[158] The Georgia Relief & Hospital Association trousers of Hamilton Branch courtesy of the AHC, author examined the trousers on 23 April 2013; CSR Georgia, M266, Roll 525, Company F, 54th Georgia Infantry, First Lieutenant H.M. Branch.

[159] The steel gray trousers of Hamilton Branch courtesy of the AHC, author examined the pants on 23 April 2013; CSR Georgia, M266, Roll 525, Company F, 54th Georgia Infantry, First Lieutenant H.M. Branch.

[160] The Cooper trousers are courtesy of the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina, (hereafter, SCCRR). The author examined the trousers on 13 July 2016. The CSR for this soldier was inconclusive, and his command affiliation is based upon the museum’s records.

[161] CSR Alabama, M311, Roll 308, 25th Alabama Infantry Regiment, J.B. Beck.

[162] The Beck trousers are courtesy of the ACWM. The author examined the Beck trousers on July 24, 2012.

[163] The Iowa souvenir jacket is courtesy of the State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines, Iowa.

[164] CSR Georgia, M266, Roll 105, Captain Hanleiter’s Company, Georgia Light Artillery, John B.L. Grizzard.

[165] The Grizzard jacket is courtesy of the TCWM, with special thanks to Gary Hendershott of Little Rock, Arkansas. The author examined the jacket on 9 September 2013.

[166] The Zehring jacket is courtesy of the Horse Soldier, now in a private collection, unknown whereabouts; CSR Tennessee, M268, Roll 133, Company A, 4th Tennessee Infantry, as Corporal Jacob C. Zehring.

[167] Clark N. Thorp jacket, private collection, viewed on Antiques Roadshow, Churchill Downs Racetrack, Louisville, Kentucky, 21 May 2019.

[168] Image courtesy of Alan T. Parker, Great Grandson, Sons of Confederate Membership directory, 1990s.

[169] The Gallaher jacket is courtesy of Joe Fitzgerald, one image courtesy of Gary Hendershott; CSR Virginia, M324, Roll 5, Company E, 1st Virginia Cavalry, Dewitt C. Gallaher. The author examined the jacket on 20 April 2013.

[170] The Sykes cap is courtesy of Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, Kennesaw, Georgia; CSR Mississippi, M269, Roll 404, Field and Staff, 43rd Mississippi Infantry, Lieutenant Colonel Columbus Sykes. The author was only able to view the artifact through the vitrine, but this on numerous occasions, with detailed notes taken on 7 May 2003.

[171] The Inabinet cap is courtesy of the SCCRR, author examined the cap on 3 July 2002; CSR South Carolina, M267, Roll 312, First Sergeant David Jacob Inabinet, 20th South Carolina Infantry.

[172] The Bowman cap is courtesy of the ACWM, author examined the cap on 24 July 2012; CSR Georgia, M266, Roll 105, Private Cicero Bowman, Company A, 5th Georgia Reserves, Captain C.D. Findlay’s Ordnance Guard at Macon, Georgia.

[173] The Anderson cap is courtesy of the Kentucky Military History Museum, Frankfort, Kentucky, author examined the cap on 1 December 2011; CSR Kentucky, M319, Roll 80, Sergeant Robert C. Anderson, Company F, 2nd Kentucky Mounted Infantry.

[174] The infantry forage cap is courtesy of Dr. Michael R. Cunningham. The author examined the cap on 25 July 2013.

Acknowledgments: