Comparing Color of Cadet Gray Kersey: Originals vs. Replicas

By Fred Adolphus, February 15, 2016

I have been studying Confederate uniforms since 1986. During that time, I have probably seen more Confederate uniforms than anyone on the planet today: the result of making this research my life’s work, a true passion. As such, I have been to museums from Salem, Massachusetts to Denver, Colorado; from Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Mobile, Alabama; and diverse places in between. Many of these museums I have visited so many times that I would have lost count had I not kept detailed journals of my travels and research. I have seen so much cadet gray cloth that I dream about it at night. And yet, with all the research trips spanning three decades, I never thought to study the color shades of original cadet gray cloth, until the autumn of 2015.

At some point in that year, I began looking at the myriad of swatches of replica cadet gray cloth that I had acquired for making living history uniforms. It irked me that there was such a range of shades in replica cadet gray, and that reenactors were overly obsessed with getting a strongly blue-toned shade. I griped about their over fondness of “blue” to fellow uniformologist, Gregg Grant. About the same time, the mill who supplied Charlie Childs with cadet gray cloth had sent him a batch that did not have enough blue tone to it. This caused Childs a considerable amount of grief in selling the off-hue, replica cloth, but it spurred me to think about what exactly the correct color tone for cadet gray should be. I had spoken to Ben Tart about this a while back, and he explained the process for dyeing wool to achieve the cadet gray color. I looked at the notes of our conversation, and realized that I needed to compare the replica cloth to the originals. I was excited about the prospect, but disappointed in myself for not having done it years before. So, moving forward in late 2015, I began making my comparisons, armed with my packet of replica cadet gray cloth swatches. This is what I found.

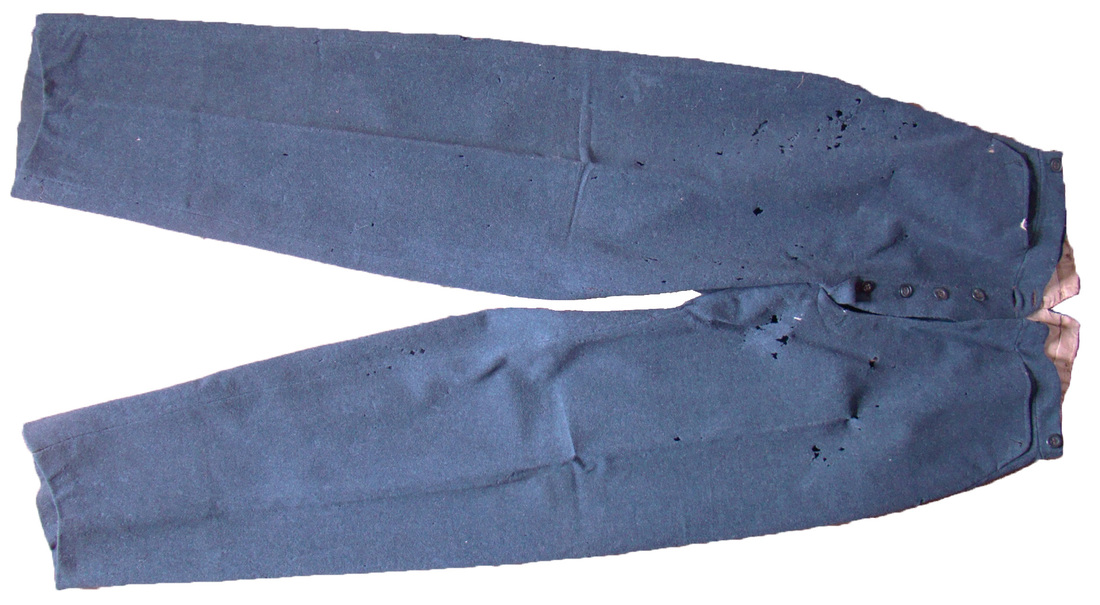

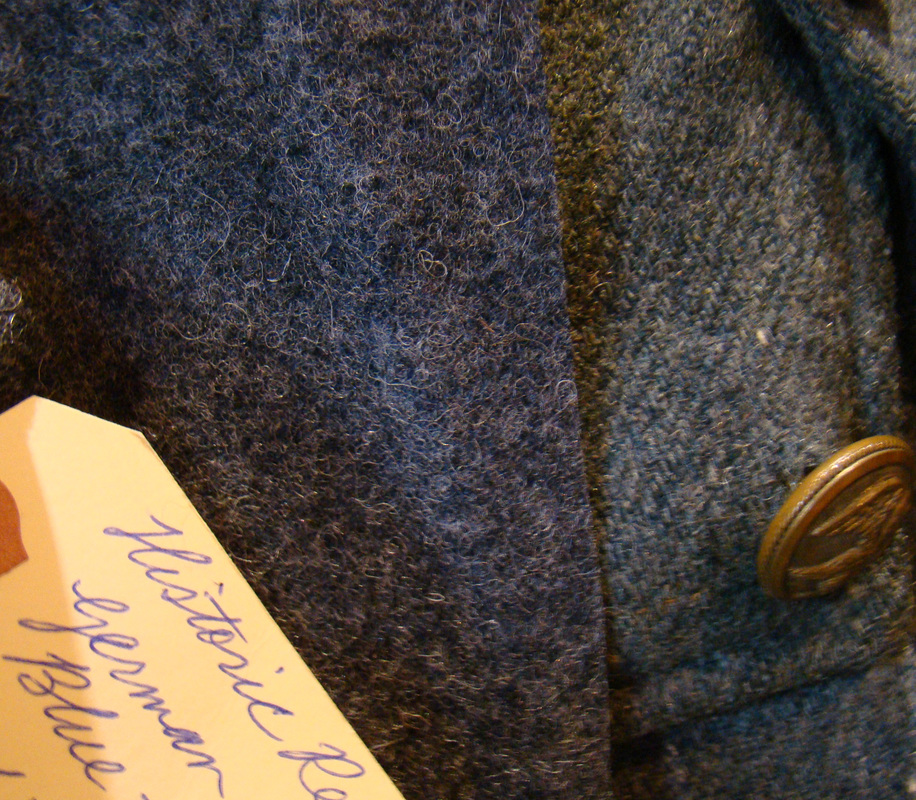

In a nutshell, replica cadet gray is too blue-toned in color, and generally too heathered in the yarn texture. Original cadet gray cloth is nearly always darker, grayer and has a more consistent finish to the yarn coloration (i.e. less heathering). The original cadet gray color has more black in the mix than its replica counterpart, which gives it its darker, grayer hue. Furthermore, having looked at scores of original cadet gray uniforms from the period of November 2015 to January 2016, I can assert that the enlisted grade cadet gray cloth was remarkably uniform in its color, texture and overall appearance.[1] All of the cadet gray uniforms, regardless of where they were made, had the same dark gray hue that I observed by comparing it with the blue-toned replica swatches.

At some point in that year, I began looking at the myriad of swatches of replica cadet gray cloth that I had acquired for making living history uniforms. It irked me that there was such a range of shades in replica cadet gray, and that reenactors were overly obsessed with getting a strongly blue-toned shade. I griped about their over fondness of “blue” to fellow uniformologist, Gregg Grant. About the same time, the mill who supplied Charlie Childs with cadet gray cloth had sent him a batch that did not have enough blue tone to it. This caused Childs a considerable amount of grief in selling the off-hue, replica cloth, but it spurred me to think about what exactly the correct color tone for cadet gray should be. I had spoken to Ben Tart about this a while back, and he explained the process for dyeing wool to achieve the cadet gray color. I looked at the notes of our conversation, and realized that I needed to compare the replica cloth to the originals. I was excited about the prospect, but disappointed in myself for not having done it years before. So, moving forward in late 2015, I began making my comparisons, armed with my packet of replica cadet gray cloth swatches. This is what I found.

In a nutshell, replica cadet gray is too blue-toned in color, and generally too heathered in the yarn texture. Original cadet gray cloth is nearly always darker, grayer and has a more consistent finish to the yarn coloration (i.e. less heathering). The original cadet gray color has more black in the mix than its replica counterpart, which gives it its darker, grayer hue. Furthermore, having looked at scores of original cadet gray uniforms from the period of November 2015 to January 2016, I can assert that the enlisted grade cadet gray cloth was remarkably uniform in its color, texture and overall appearance.[1] All of the cadet gray uniforms, regardless of where they were made, had the same dark gray hue that I observed by comparing it with the blue-toned replica swatches.

At this point, I’ll explain something of how cadet gray cloth is manufactured, as explained to me by noted chemist and uniformologist, Ben Tart; historic cloth specialist, Charles R. Childs; and, English Confederate export historian, Dave Burt.

According to Ben Tart, weavers during the Civil War made cadet gray cloth by mixing indigo-dyed, medium to dark blue wool with white wool at a rate of 50% blue and 50% white, or 60% blue and 40% white. The black wool was mixed in at a proportion of 1/6, 1/8, or 1/12 of the batch. The black wool was produced by dyeing clean, white wool with logwood dye. Sometimes, the logwood dyed wool would be further dyed with dark blue indigo dye to make it yet blacker. As one might surmise, with all the variables posited, the range of shades for the cadet gray color would be numerous.

Dave Burt weighed on the discussion, as well. He had studied the records of the Joshua Ellis Mill of Yorkshire, England, and found color “recipes” for original cadet gray cloth, and determined that Ellis had made the cadet gray cloth for the Peter Tait uniform contracts.[2] Accordingly, Ellis used 70% blue and 30% gray colorfast dyestuffs in making the Peter Tait contract cloth. Ellis’s process began by cleaning the wool fiber with large quantities of clean, soft water. Ellis had a large reservoir of soft water at his mill, and the more water he used to clean the wool, “…the better and faster the colours,” could be dyed into the wool. Once thoroughly cleaned, the wool fiber was dyed. The term “dyed in the wool” comes from this practice. The Confederate contract for the Tait uniforms called for “fast dye” to be used in the cloth for the trousers and jackets, and these uniforms today bear witness to the color fastness of Ellis’s cadet gray dye.

Burt explained further that gray wool was produced by mixing black and gray (undyed white?) wool fibers together to render the desired shade for the gray component of the final mix. Likewise, clean white wool fiber was dyed blue for the blue component. The gray and blue components were then mixed to get the desired cadet gray color, and once the wool was of the right color, it was spun into yarn.

Burt had not found in the records the ingredients for making black dye, but he determined that indigo was the most commonly used industrial blue dye in England by 1860. Woad had fallen out of general usage by the late eighteenth century since European dyers could obtain indigo much easier. The mineral dye “Prussian blue” was also in general use at this time, and Ellis used it for at least for part of his production. Ellis’s records mention that he used Prussian blue dye for making the royal blue trim cloth used for the collars, shoulder straps and edging of the Peter Tait contract uniforms.

Charlie Childs, having over thirty years of experience in dealing with American mills that make replica cadet gray cloth, offered his insights about the process. The cadet gray color is achieved by mixing blue-dyed woolen fiber with undyed fiber, and combing them together to homogenize the color mix. The blue batch is then mixed and combed in with the black wool component to get the final cadet gray color. The cadet gray wool would then be spun into yarn. Childs added that by varying the proportions of dyed and undyed fiber, as well as changing the proportion of black fiber, the number of shades is limitless. Other factors affecting the finished appearance include: whether the undyed fiber is natural white, yellowish-white or sheep’s gray; the type of dyestuff used to achieve the blue color; and, the degree of fulling in the finished fabric.

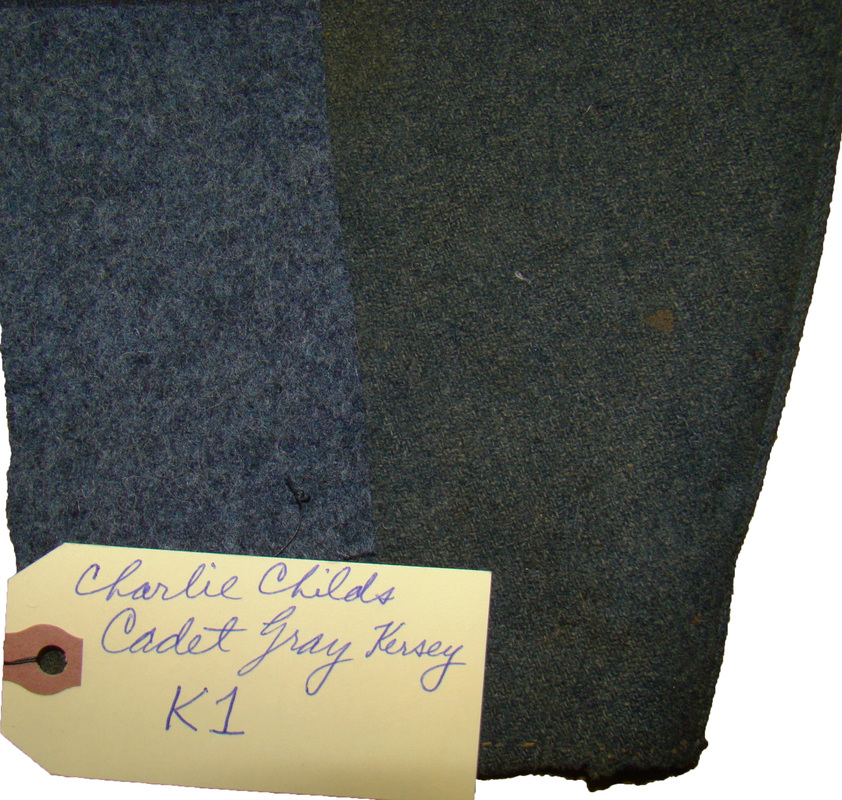

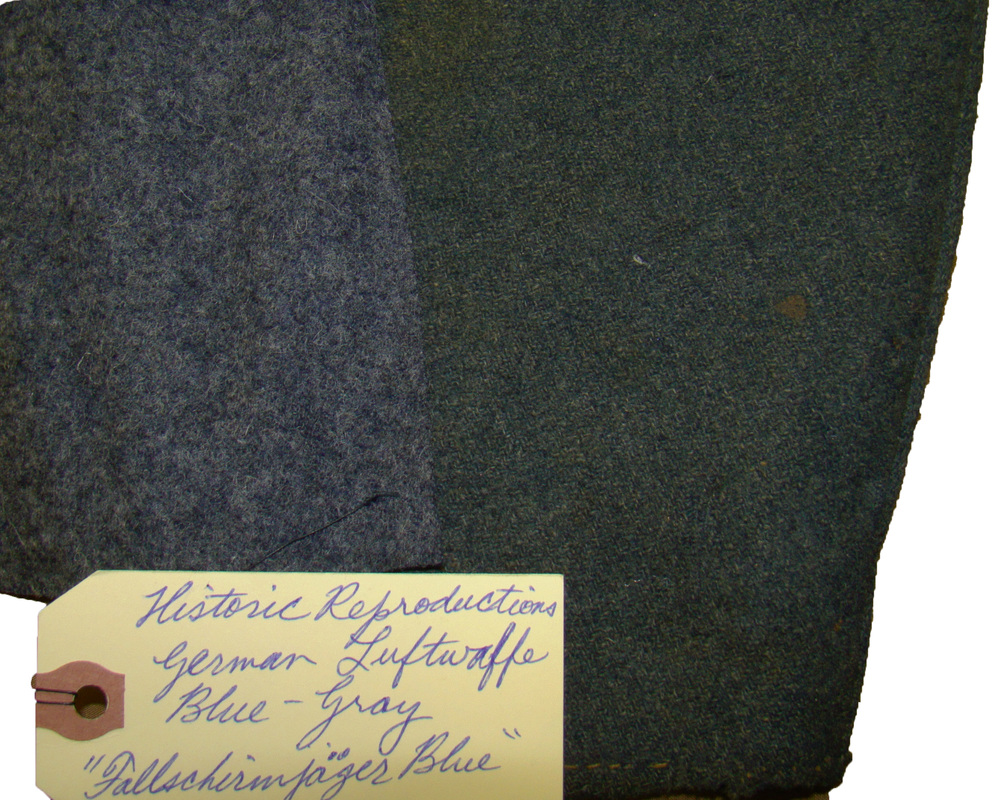

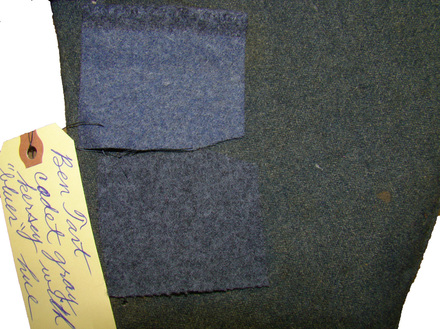

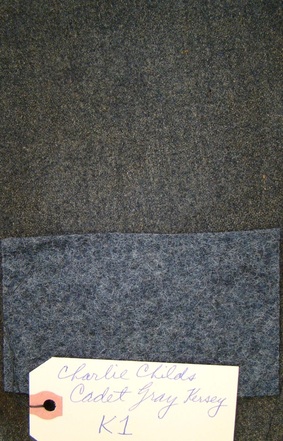

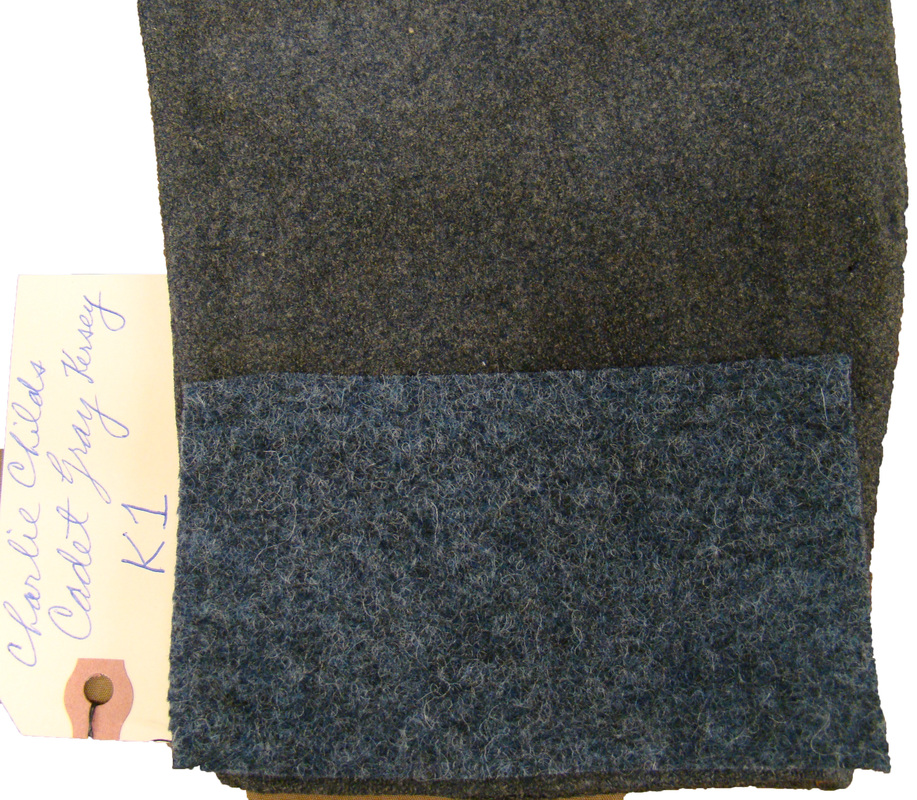

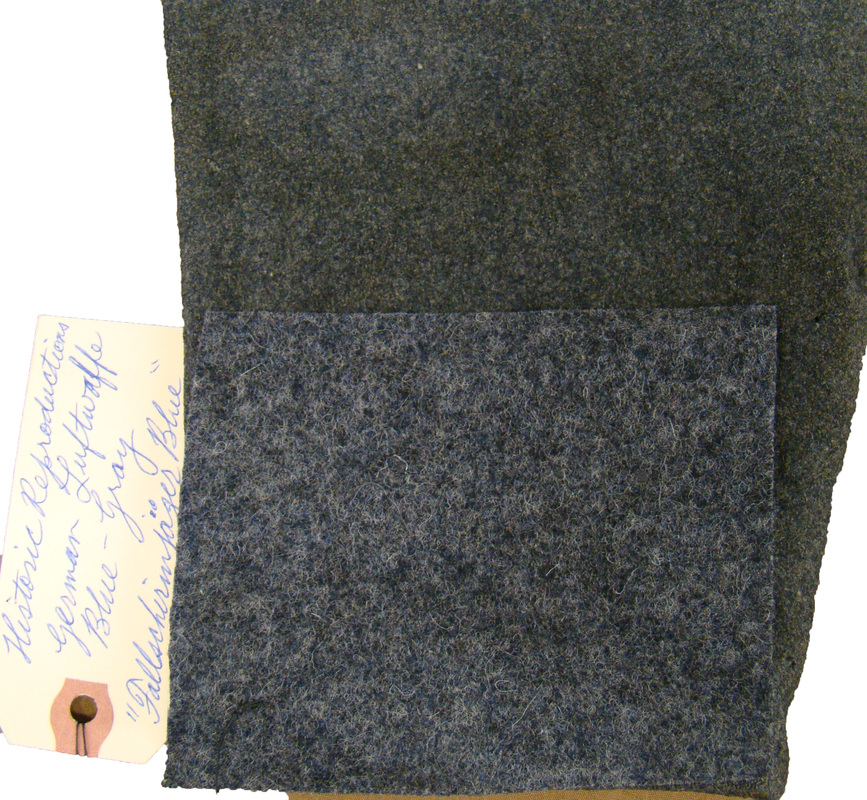

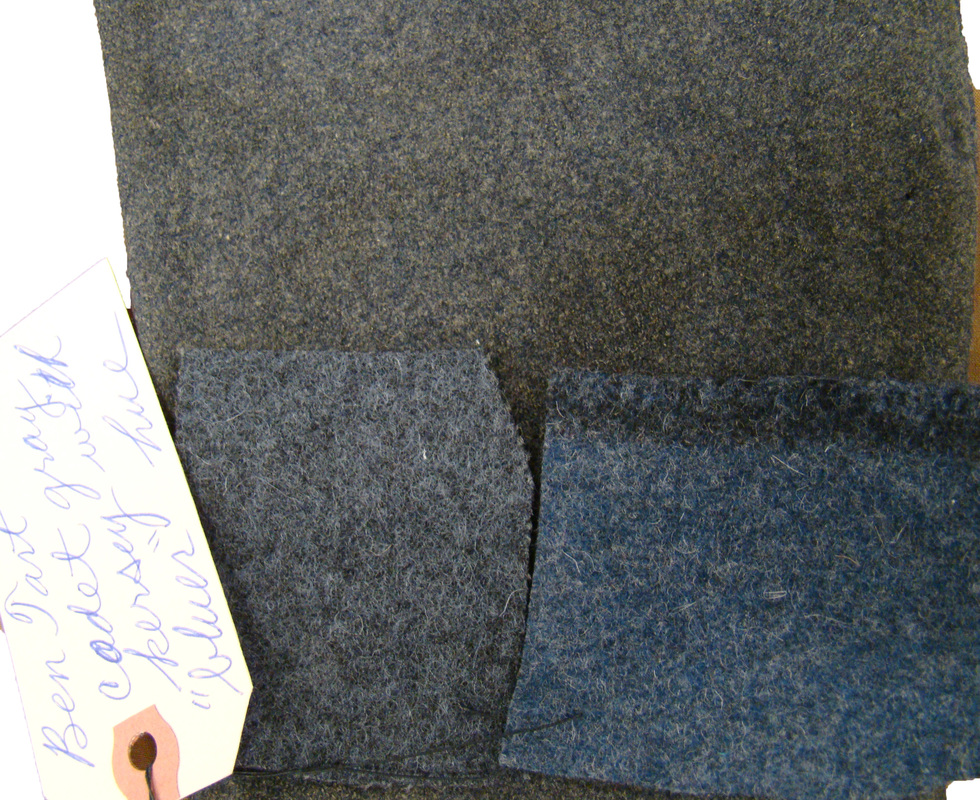

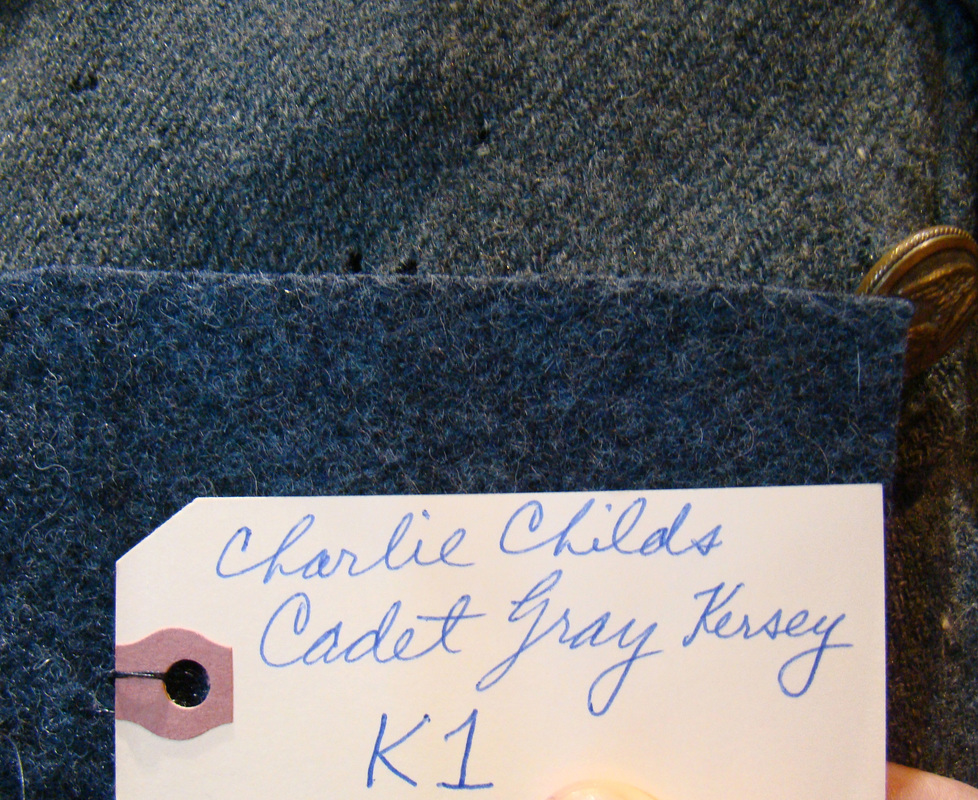

Having considered how replica cadet gray cloth is made, I will now compare how the various replicas shades compare to the original shades. My swatch packet contained four samples of replica, cadet gray kersey: one was Charlie Childs, County Cloth, “K1” kersey; the next was Historic Reproductions Fallschirmjaeger (WW2 Luftwaffe) blue; one was Ben Tart’s blue-gray kersey; and, the last was M.J. Cahn's cadet gray cloth.

According to Ben Tart, weavers during the Civil War made cadet gray cloth by mixing indigo-dyed, medium to dark blue wool with white wool at a rate of 50% blue and 50% white, or 60% blue and 40% white. The black wool was mixed in at a proportion of 1/6, 1/8, or 1/12 of the batch. The black wool was produced by dyeing clean, white wool with logwood dye. Sometimes, the logwood dyed wool would be further dyed with dark blue indigo dye to make it yet blacker. As one might surmise, with all the variables posited, the range of shades for the cadet gray color would be numerous.

Dave Burt weighed on the discussion, as well. He had studied the records of the Joshua Ellis Mill of Yorkshire, England, and found color “recipes” for original cadet gray cloth, and determined that Ellis had made the cadet gray cloth for the Peter Tait uniform contracts.[2] Accordingly, Ellis used 70% blue and 30% gray colorfast dyestuffs in making the Peter Tait contract cloth. Ellis’s process began by cleaning the wool fiber with large quantities of clean, soft water. Ellis had a large reservoir of soft water at his mill, and the more water he used to clean the wool, “…the better and faster the colours,” could be dyed into the wool. Once thoroughly cleaned, the wool fiber was dyed. The term “dyed in the wool” comes from this practice. The Confederate contract for the Tait uniforms called for “fast dye” to be used in the cloth for the trousers and jackets, and these uniforms today bear witness to the color fastness of Ellis’s cadet gray dye.

Burt explained further that gray wool was produced by mixing black and gray (undyed white?) wool fibers together to render the desired shade for the gray component of the final mix. Likewise, clean white wool fiber was dyed blue for the blue component. The gray and blue components were then mixed to get the desired cadet gray color, and once the wool was of the right color, it was spun into yarn.

Burt had not found in the records the ingredients for making black dye, but he determined that indigo was the most commonly used industrial blue dye in England by 1860. Woad had fallen out of general usage by the late eighteenth century since European dyers could obtain indigo much easier. The mineral dye “Prussian blue” was also in general use at this time, and Ellis used it for at least for part of his production. Ellis’s records mention that he used Prussian blue dye for making the royal blue trim cloth used for the collars, shoulder straps and edging of the Peter Tait contract uniforms.

Charlie Childs, having over thirty years of experience in dealing with American mills that make replica cadet gray cloth, offered his insights about the process. The cadet gray color is achieved by mixing blue-dyed woolen fiber with undyed fiber, and combing them together to homogenize the color mix. The blue batch is then mixed and combed in with the black wool component to get the final cadet gray color. The cadet gray wool would then be spun into yarn. Childs added that by varying the proportions of dyed and undyed fiber, as well as changing the proportion of black fiber, the number of shades is limitless. Other factors affecting the finished appearance include: whether the undyed fiber is natural white, yellowish-white or sheep’s gray; the type of dyestuff used to achieve the blue color; and, the degree of fulling in the finished fabric.

Having considered how replica cadet gray cloth is made, I will now compare how the various replicas shades compare to the original shades. My swatch packet contained four samples of replica, cadet gray kersey: one was Charlie Childs, County Cloth, “K1” kersey; the next was Historic Reproductions Fallschirmjaeger (WW2 Luftwaffe) blue; one was Ben Tart’s blue-gray kersey; and, the last was M.J. Cahn's cadet gray cloth.

As I mentioned previously, the shade of original cadet gray was far more consistent than I expected. Most notably, however, was the hue of the cloth: it was a darker, grayer shade than the replicas. The replicas were all bit lighter and too blue-toned. The originals appear to have much more black in the mix. By and large, Ben Tart’s cloth was very close to the originals, but a bit too blue. Historic Reproductions was the grayest of all but far lighter than any of the originals except for the Brunet uniform. The Brunet uniform was made from a batch of lighter, grayer cadet gray kersey, and Historic Reproductions came very close to matching it. The County Cloth K1 came closest of all to the originals, but is still distinctly blue by comparison. M.J. Cahn's cloth is far too blue to even be considered close to the orinal uniforms. In all cases, the replica kerseys need far more black to match the original color.

The original kerseys do not have as much heathering as the replicas, the coloration being more consistent across the surface. One of the Tart samples appeared to be less heathered than the rest of the replicas in the swatch packet.

As to weight of wool, the County Cloth K1 and Historic Reproductions Fallschirmjaeger are the closest to the originals, with the K1 being fairly spot on. The Ben Tart cloth is a bit too light in weight, but not too far off the mark. M.J. Cahn's cloth is the lightest of all.

Finally, I would like to reiterate that one of the most remarkable observations I made was about the uniformity of the color in the original, enlisted uniforms, and officer uniforms in large part. Regardless of where the uniforms were made, be it Richmond, Limerick, the Carolinas, the Trans-Mississippi, Alabama, wherever, the color shade was the same throughout: a very dark, gray-toned, cadet gray. I observed very little if any variation of color shades in the original cadet gray cloth. When I encountered differences, they amounted to subtle nuances.[3] Exceptions were few, and these included, as noted, the lighter, more gray-toned Brunet uniform, and officers’ uniforms, many of which employed a wide spectrum of cadet gray shades, but the dominant shade remained the same as the dark, gray-toned shade of the enlisted cloth. I never cease to be amazed at how colorfast this imported, cadet gray cloth is, even after 150 years.

I need to also write a caveat regarding blue shades and photography. Throughout my travels, I have taken thousands of pictures of cadet gray cloth. The problem with this is that the true shade of cadet gray as seen in person rarely conveys well in my color photography. Lighting always plays a major role in how gray or how blue, or how light or how dark the cadet gray color will appear. Under fluorescent lighting, cadet gray can appear lighter and grayer. Direct sunlight can make the color appear lighter, brighter and bluer. A position in balanced, natural light without direct sunlight or artificial lights, and without a flash, will sometimes render a very true-to-life shade. Likewise, when I am shooting indoors without access to balanced, natural light, I have to use a flash, and this yields mixed results. Finally, I am no photographer. I am just a uniformologist with a camera, fumbling along and learning some tricks as I go. As any photographer can tell, black and blue are tough colors to get right in a photo. The bottom line is, many of my photos of cadet gray cloth have color distortion, and the cadet gray shade one sees is not necessarily the true-to-life shade of the cloth. I have mitigated many of the mistakes in my more recent images. Let readers be warned: take the color in my images with a grain of salt.

I have compared original to replica cadet gray cloth, and in doing so, I have rendered some stringent critiques on the replica products available on the market today. I mean nothing personal by it: it is just an historical study. In fact, I have respect for the persevering few who provide the living history community with the cadet gray cloth that they make. Folks like Charles R. Childs, Ben Tart, Pat Kline and Ken Boice spent enormous amounts of time, research and money to produce cadet gray cloth that reenactors can enjoy. The living history community owes these people a great debt for the service and products they provide: all just so that we can wear historically accurate uniforms and have fun. These guys have also spent untold hours on the phone with me, or writing me emails, to explain how this cloth is made and dyed: all time out of their busy days.

Okay, so the color shade of their cadet gray cloth may not be just perfect. But consider for a moment all the jackasses that these folks have to deal with at the mills, or wherever, to obtain the cloth in bulk that we buy four or five yards at a time. Not only do they deal with erratic mill owners, they deal with any number of reenactors who offer trifling criticisms and minuscule orders for cloth. Few really understand the headaches that these guys go through to provide us with our replica cadet gray cloth. So, while I have critiqued replica cadet gray kersey, I am not carping about it. I’m just grateful that our suppliers are there. Those who want to complain should put their own money into buying five hundred to a thousand yards of cadet gray cloth, and see first-hand the problems involved with acquiring and selling it.

All that aside, my research stands for what it is worth. I hope that uniformologists and weavers will find my conclusions useful.

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank all who helped me with this study, including Charles R. Childs, County Cloth, Paris, Ohio; Ben Tart, Garner, North Carolina; David Burt, Congleton, England; and, Pat Kline, Pennsylvania. I am also indebted to those who opened their collections to me: Michael Kramer; Pat Ricci, Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana; Wayne Phillips, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana; James Peterson, History Colorado Museum, Denver, Colorado; and, Maggie Brown, Museum of Southern History, Houston Baptist University, Houston, Texas.

Image copyrights: Readers are reminded that all of the images in this study are the property of Adolphus Confederate Uniforms, regardless of which collection the actual artifacts reside in. The images may not be used in any form without the consent of the author.

Bibliography

[1] I inspected every single, solitary uniform at Confederate Memorial Hall as part of a comprehensive inventory and identification project; and I looked at the Brunet uniform in Houston, the Durham jacket in Denver, and the Bach jacket in New Orleans. By “inspected” and “looked at” I mean that I actually handled the artifacts in most cases, and at a minimum, for just a few of the uniforms, looked at them in the exhibit cases.

[2] Hansards Parliamentary Papers that Ellis gave evidence to in the 1860s (reference provided by David Burt).

[3] Jones, J.B., A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, Volume II, J.B. Lippincott & Co., Philadelphia, 1866, reprint of 1982, Time Life inc., pp. 344 and 347, On December 1 and 4, 1864, Jones mentioned that he had bought four yards of cloth from the quartermaster in Richmond that he described as “dark-gray cloth," remarking that it was "too dark for the army.” These passages strongly suggest that some of the cadet gray cloth imported for the Confederate army was too dark blue in color to pass for Confederate gray, and in fact resembled the Yankee dark blue. In such cases, it would seem that were occasional variations in the shade of cadet gray, Confederate army cloth.