Confederate Depot Uniforms of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, 1864-1865, Part II: The Jackets of Captain William M. Gillaspie's Depot, Selma and Montgomery, Alabama

By Frederick R. Adolphus, March 26, 2016; Updated August 27, 2016

Continued from Part I: click here to navigate back to the previous page...

Now turning to the Montgomery-dubbed jacket, it has these features. The weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. The cotton warp is a heavy yarn, ranging in color from a bleached white to a natural white to a light golden brown. The woolen weft yarn color ranges from a light sheep's gray to tan to brownish-gray to steel gray. The fabric color often has a striped, or brindled appearance due to heterogeneous-colored fill yarn used intermittently that results in darker and lighter stripes in the weft.[42] These observations suggest that the jackets were originally either a natural, undyed sheep’s gray or a dyed steel gray (the brindling having little effect on the overall color). The lining is an unbleached cotton osnaburg, without an interior pocket. The jackets are tailored with a six-piece body, one-piece sleeves, one exterior inset pocket at the left breast, seven-button front, and, a one-piece collar (inside and out). Of three interior innings observed by the author, two were cut with facing lapels that extend at the top all the way to the back piece, essentially separating the interior collar facing from the front lining. Most extant jackets retain their wooden, two-hole, Confederate depot buttons. Furthermore, most of these jackets have a double-row of topstitching around the edge, the stitching closest to the edge having been applied in lieu of an interior-stitched seam that had to be turned and pressed. Some are cut straight across the back plackets at the bottom edge, and some are made with a slight point. All but one of the originals have squared front lapel bottoms. The Montgomery jackets are all very similar to one another, without any notable variants as observed in other depot jackets. There are seven surviving Montgomery jackets and two of them have accompanying, matching trousers.

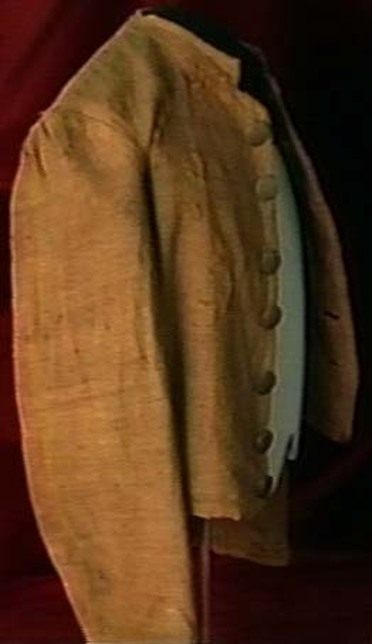

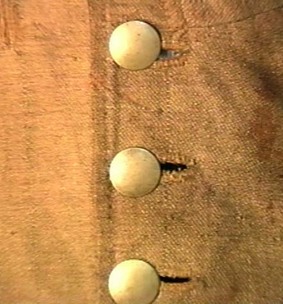

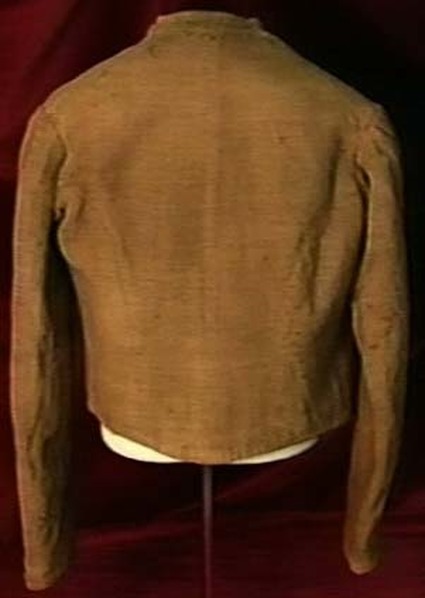

The first of these jackets, from whence the provenance to Montgomery derives, is the one worn by Sergeant H.P. Kingsley, 2nd New York Cavalry. Kingsley, as previously stated, was interned along the Selma-Montgomery rail line at Cahaba Prison, where he received the jacket. The weave is inconclusive based on low resolution of the images I have available, but appears to be similar to other Montgomery jackets. The overall color is a homogenous tan due to uniformly-colored fill yarn used throughout. Seven intact, flat brass, penny buttons, approximately one inch in diameter, are attached to the front. The exterior pocket welt is situated between the third and fourth (middle) buttonholes from the top. The jacket has a single row of backstitched, topstitching that extends all the way around the edge of the jacket. The topstitching on the collar is set about a third of the way down from the top edge. The bottom edges of the back plackets have a slight point.[43]

Now turning to the Montgomery-dubbed jacket, it has these features. The weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. The cotton warp is a heavy yarn, ranging in color from a bleached white to a natural white to a light golden brown. The woolen weft yarn color ranges from a light sheep's gray to tan to brownish-gray to steel gray. The fabric color often has a striped, or brindled appearance due to heterogeneous-colored fill yarn used intermittently that results in darker and lighter stripes in the weft.[42] These observations suggest that the jackets were originally either a natural, undyed sheep’s gray or a dyed steel gray (the brindling having little effect on the overall color). The lining is an unbleached cotton osnaburg, without an interior pocket. The jackets are tailored with a six-piece body, one-piece sleeves, one exterior inset pocket at the left breast, seven-button front, and, a one-piece collar (inside and out). Of three interior innings observed by the author, two were cut with facing lapels that extend at the top all the way to the back piece, essentially separating the interior collar facing from the front lining. Most extant jackets retain their wooden, two-hole, Confederate depot buttons. Furthermore, most of these jackets have a double-row of topstitching around the edge, the stitching closest to the edge having been applied in lieu of an interior-stitched seam that had to be turned and pressed. Some are cut straight across the back plackets at the bottom edge, and some are made with a slight point. All but one of the originals have squared front lapel bottoms. The Montgomery jackets are all very similar to one another, without any notable variants as observed in other depot jackets. There are seven surviving Montgomery jackets and two of them have accompanying, matching trousers.

The first of these jackets, from whence the provenance to Montgomery derives, is the one worn by Sergeant H.P. Kingsley, 2nd New York Cavalry. Kingsley, as previously stated, was interned along the Selma-Montgomery rail line at Cahaba Prison, where he received the jacket. The weave is inconclusive based on low resolution of the images I have available, but appears to be similar to other Montgomery jackets. The overall color is a homogenous tan due to uniformly-colored fill yarn used throughout. Seven intact, flat brass, penny buttons, approximately one inch in diameter, are attached to the front. The exterior pocket welt is situated between the third and fourth (middle) buttonholes from the top. The jacket has a single row of backstitched, topstitching that extends all the way around the edge of the jacket. The topstitching on the collar is set about a third of the way down from the top edge. The bottom edges of the back plackets have a slight point.[43]

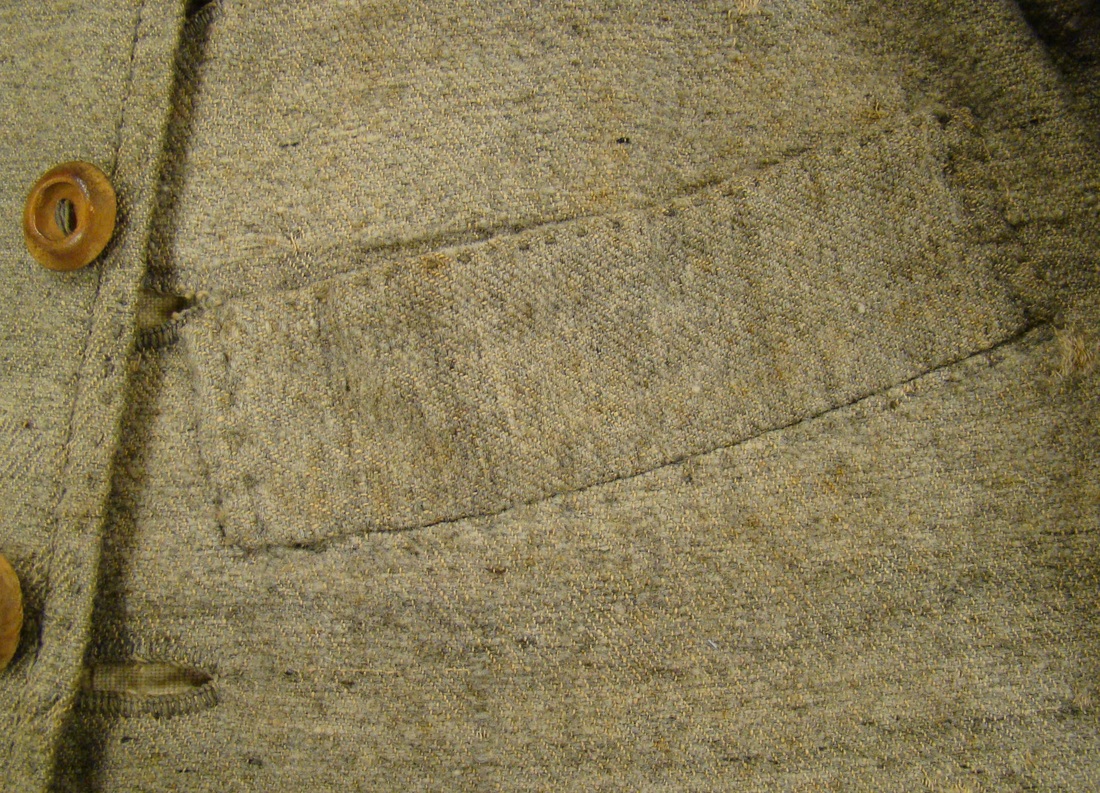

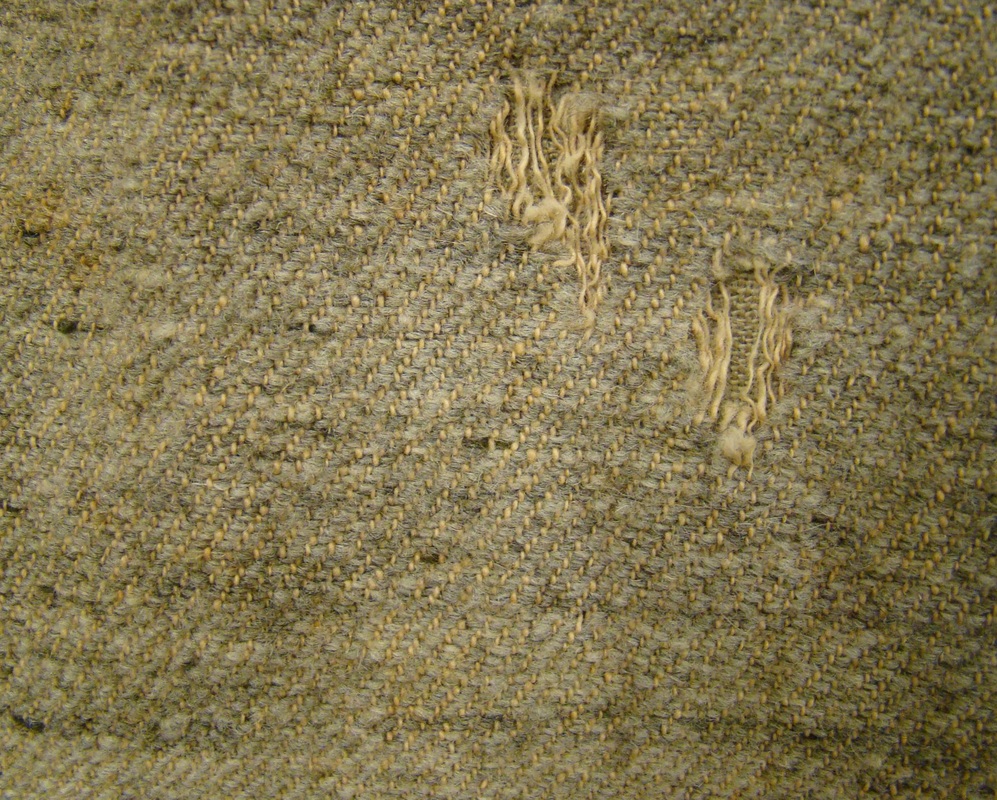

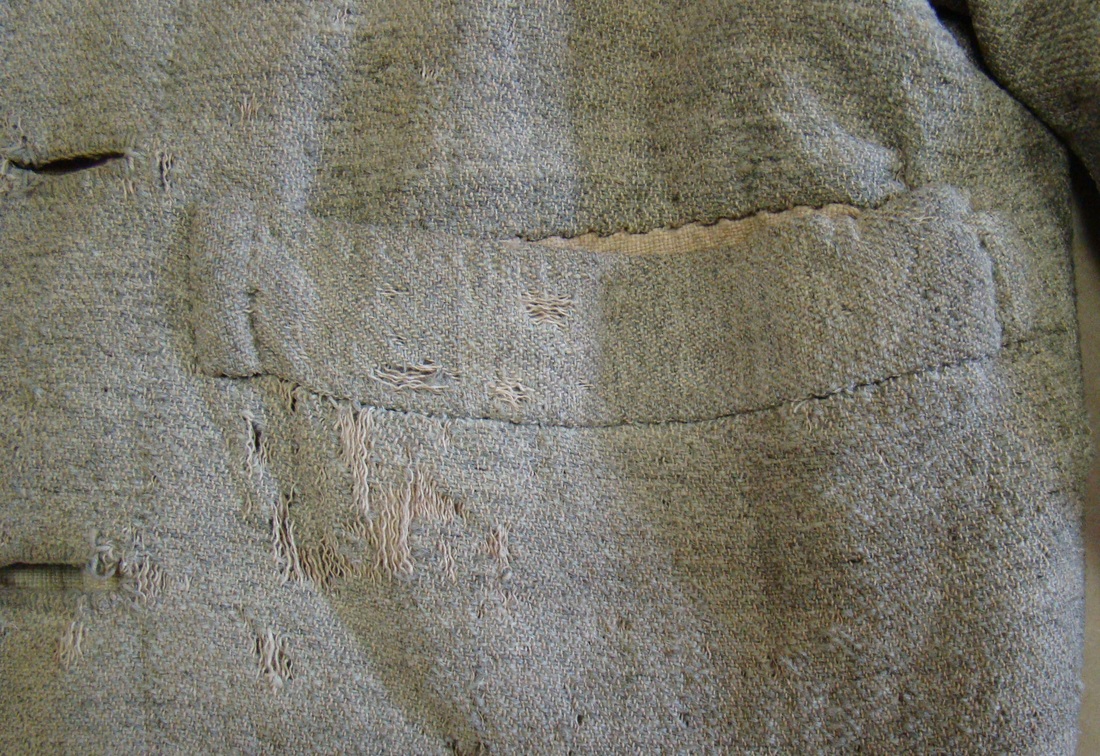

The second jacket has no provenance, but is a splendid example of a Montgomery uniform, and it includes a pair of matching pants. In lieu of provenance, the set is named by its catalog numbers from the Gettysburg National Park: the jacket GETT 29076, and the pants GETT 29077. The weave for both the jacket and pants, that match exactly, is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. The cotton warp yarn is a light tan color; the woolen weft yarn is a sheep's gray color; fabric color has a striped, or brindled appearance due to heterogeneous-colored fill yarn used intermittently in the weft. The jacket has all seven of its wooden Allen buttons intact. The top of the exterior pocket welt aligns with the middle buttonhole, and, in fact, overlaps a little onto it. The double-row of topstitching, extending all the way around the jacket’s edge, is finished with backstitching. The exterior stitch (closest to the edge) is rather widely spaced. The interior stitch, around the body only, is much tighter. The interior topstitch around the collar is machine-stitched. The thread tension for machine-stitching along the collar edge was mal-adjusted and loose, which may explain why the rest of the topstitching for this row around the body’s edge was completed by hand. The bottom edge of the back plackets is cut straight across. The facing lapels are cut in the typical fashion in that they are not so wide they extend to the back lining piece and separate the front lining from the collar lining. The matching trousers have the same wooden Allen buttons as the jacket, except in the five-eighths inch pants size; a buttoning rear adjustment belt (also with an Allen button); and, the brindled fabric matches that of the jacket exactly. There is every reason to believe that the GETT 29077 trousers were made at the Montgomery Depot. More details on the trousers follow in the descriptions of all the pants together.[44]

10a. This shows the front of Montgomery jacket identified only by its catalog number, GETT 29076. One of the most salient features is the brindling throughout the fabric. This feature is noted in many of the Montgomery uniforms. A Federal soldier even remarked about it in March 1862 when he described Confederate prisoners from Fort Donelson as dressed in "uniforms of all shades of colors, gray, brindle, and butternut, the last predominating." The artifact in the 10-series of images is courtesy of the Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

10o. This view of the collar shows the same double row of topstitching that is observed in the lapel's front edges. The outer row is a widely spaced backstitch. The interior row of topstitching was applied with a sewing machine. The interior collar facing was laid over the lining, the edge folded inward, and then whipstitched in place. Details of the buttonhole construction are also visible. The buttonhole was sewn with the same gray-dyed thread used in the topstitching, and the stitches are very closely-spaced and sturdy. The collar's one-piece construction is also evident here.

The third jacket, yet another without provenance, resides in the Smithsonian Institution, and is referred to by its accession number: 1980.0399.0921. The jacket is typical of most Montgomery jackets, except that the bottoms of the front lapels are slightly rounded. Its weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. The cotton warp yarn is a light, golden brown color; the woolen weft yarn is a sheep's gray, or light steel gray color. Fabric color has a slightly striped appearance due to heterogeneous-colored fill yarn used intermittently in the weft. The jacket has all seven of its wooden Allen buttons intact. The exterior pocket welt aligns between the middle buttonhole and the one below it. The double-row of topstitching is sewn with a widely spaced backstitch all the way around the jacket’s edge. The exterior stitch (closest to the edge) is widely spaced and the interior stitch is a bit more closely spaced. The interior stitch is placed close to the edge of the collar, rather than towards the center. The bottom edge of the back plackets is cut almost straight across. The facing lapels at the top extend all the way to the back piece, between the interior collar facing and the top of the front lining piece.[45]

11a. This shows the front of Montgomery jacket identified only by its catalog number, 1980.0399.0921. This jacket is nearly identical to the GETT 29076 jacket, to include the characteristic brindling so common to Montgomery uniforms. The artifact in the 11-series of images is courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

11o. The inside of the collar shows its basic construction as well as a noteworthy feature found in some of the Montgomery jackets. Namely, the facing lapels at the top extend all the way to the back piece, which effectively separates the interior collar facing and the top of the front lining piece. The weave of the typical osnaburg lining is clearly visible in this image.

11q. Other than the cut of the front lining piece at the top, the lining of the Catalog # 1980.0399.0921 jacket is typical of the other Montgomery jackets. The bottom edge has a double row of topstitching. The outer row is actually whipstitched, but shows through the front, and the inner row is backstitched.

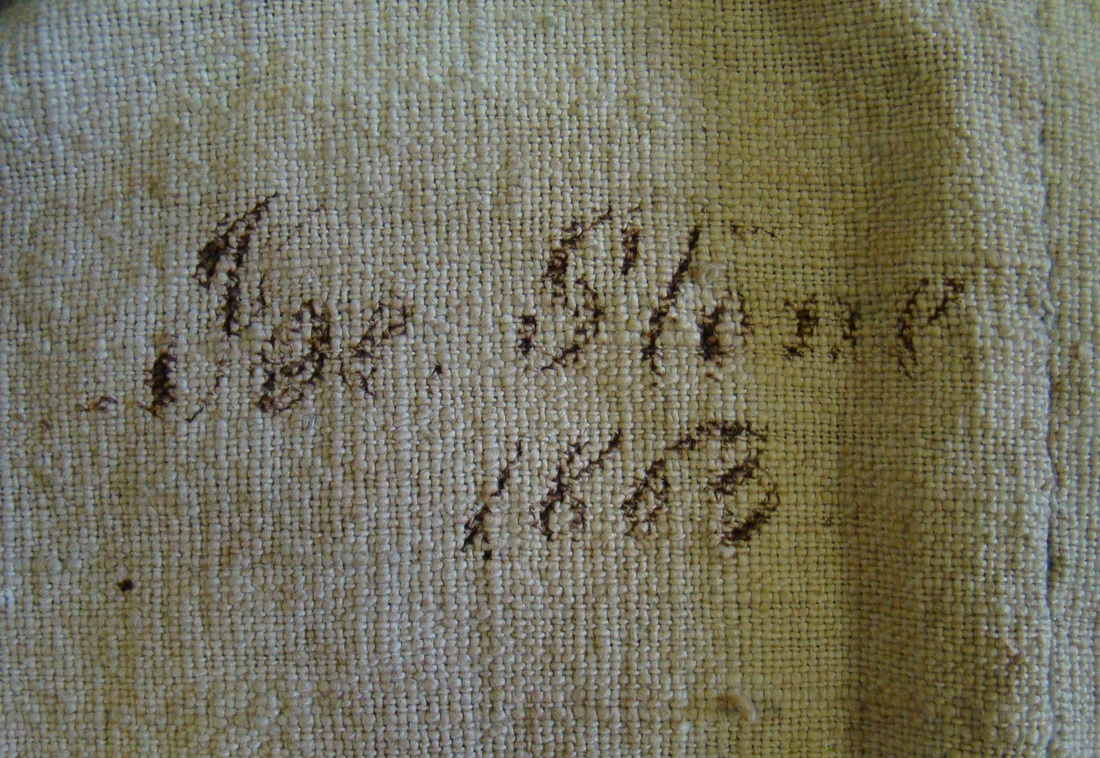

The fourth jacket was worn by Joseph Newman Stone, who served in three different commands during the war. His first service was with Company G, 1st Confederate Infantry, having enlisted in April 1861. After twelve month’s service with the 1st Confederate, Stone re-enlisted with the 32nd Alabama Infantry as a musician, being temporarily detailed to the 6th and 9th Tennessee Consolidated Regiment while serving with the 32nd. In March 1863, he joined Buck's Escort Company, Mississippi Cavalry as a bugler. He remained with this company until the end of the war, surrendering in North Carolina.[46] Stone may have received his Montgomery jacket at the Mobile hospital while recovering from a gunshot wound received at Chickamauga. This possibility is strengthened by the fact that he penned onto the jacket lining, "Jos. Stone 1863." It is doubtful, however, that the jacket would have lasted from November 1863 to April 1865. More likely, he received the jacket while his command was near Corinth, Mississippi following the Tennessee Campaign in January 1865. His command would have had a perfect opportunity to draw clothing from the department’s supplies. In any case, Stone's jacket is identical to the other Montgomery jackets, except that the bottom edge has been shortened enough to remove the bottom button. The original buttons may have been replaced by the Federal eagle "I" buttons that are now on the jacket. The weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. The cotton warp yarn is a heavy, bleached white color; the woolen weft yarn is a light sheep's gray color. Fabric color has a striped appearance due to heterogeneous-colored fill yarn used at distinct intervals. The exterior pocket welt falls between what was originally the middle buttonhole (now third from the bottom) and the one above it, actually with the top of the welt almost even with the upper buttonhole, and the lower edge of the pocket welt about its full width above the lower buttonhole. The jacket does not have a double-row of topstitching. Instead there is a single row, basting stitch all around, even along the bottom edge where the length was shortened. The bottom edge of the back pieces is cut with a distinctly rounded dip, although it must be reiterated that the bottom edge of the jacket has been considerably shortened. The facing lapels in Stone’s jacket are similar to those in the Smithsonian 1980.0399.0921 jacket: the top extends all the way to the back piece, between the interior collar facing and the top of the front lining piece.[47]

12e. The front lapels have only a single row of topstitching: a basting stitch or a very widely spaced backstitch. At some point, the jacket's original Confederate buttons were replaced with Federal infantry buttons. The buttonholes are well-made, and sewn with the same gray thread seen in other Montgomery jackets.

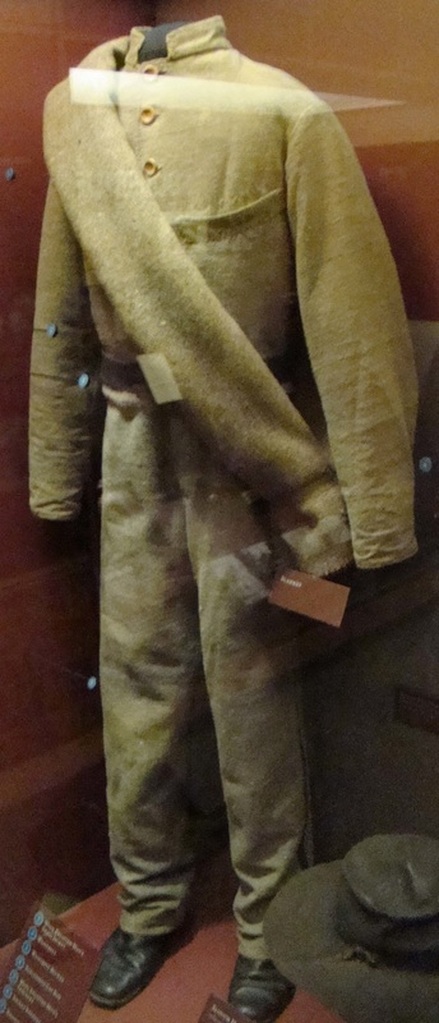

The fifth Montgomery jacket was worn by George Jacob Mook, Company D, 4th Missouri Cavalry. Mook’s jacket is accompanied by a pair of pants. Mook was captured at Mound City, Kansas during Price's ill-fated Missouri Campaign of 1864. He was interned at the Alton, Illinois Military Prison until being exchanged in February 1865, and sent to Richmond, Virginia on March 1, 1865.[48] From there, he and the other exchanged Missouri soldiers were sent to Mobile to serve in the Missouri Brigade. Once in Mobile, Mook received his Montgomery jacket. The warp yarn is a tan-colored cotton. The woolen weft is a brownish-gray (originally steel gray) color. The fabric has an overall striped appearance due to heterogeneous-colored fill yarn used at used intermittently in the weft. The jacket has all seven of its wooden Allen buttons intact. The exterior pocket welt is centered on the middle buttonhole. The bottom edge of the back plackets have a slight point. There is but a single row of topstitching around the edge of the jacket: a basting stitch. The topstitching around the collar is about a third if the collar's height down from the top. Mook’s trousers do not match his jacket. These are described in detail with the other trousers.[49]

The sixth jacket was worn by Samuel Powell Cooper of an undetermined South Carolina command. Cooper is believed to have joined the service in that last months of the war. He died of unstated causes in May 1865, Raleigh, North Carolina at seventeen years of age.[50] We can surmise that he had served in the Carolina Campaign, and that his command was one that had transferred to the Carolinas after the Tennessee campaign. This tenuous presumption is based entirely upon where he died and his jacket being from the Montgomery Depot. Despite to sketchy details of Cooper’s service, jacket is authentic and is accompanied by a pair of non-matching pants, possibly cassinet, from a different quartermaster depot. The pants are discussed in the “trousers” section of this study. The jacket is identical to the other Montgomery jackets. The weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. The cotton warp yarn is a heavy, bleached white color; the woolen weft yarn is a light sheep's gray color. All the buttons are missing. Fabric color has a slightly striped appearance due to heterogeneous-colored fill yarn used at distinct intervals. The exterior pocket welt falls between the middle buttonhole and the one above it, in fact, extending into the space between the two buttonholes, with the top of the welt starting in the middle of the buttonhole above and at the inside edge of the middle buttonhole. The double-row of topstitching is sewn with a basting stitch and extends all the way around the jacket’s edge. The exterior stitch (closest to the edge) appears to have been a bit more widely spaced than the interior stitch. The interior stitch is also placed close to the edge of the collar, rather than towards the center. The bottom edge of the back plackets is cut straight across.[51]

14a. Cooper's jacket is an udyed, sheep's gray color, and has the double row of topstitching all around the collar and body. The artifact in the 14-series of images is courtesy of the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina; photographs provided by Neill Rose, Camden, South Carolina.

A last Montgomery jacket, another in the Gettysburg collection, is without provenance but includes an accompanying pair of trousers. These artifacts can only be identified by their catalog numbers: the jacket GETT 29259, and the matching pants GETT 29260. I could draw no definitive conclusions about the artifacts because I viewed them when they were on exhibit in a dark gallery, behind glass, and their features were obscured by the jacket covering the top of the pants, and accoutrements and a bedroll covering significant parts of both the jacket and pants. The weave of both garments was difficult to observe, but they appeared to be different. The jacket fabric may have been cassinet and the pants jeans. The thick nap of the pants fabric make an accurate assessment impossible. The jacket’s overall color is tannish, and the pants are a grayish-tan. The colors for both are fairly consistent since both have a homogenous-colored weft. The jacket’s wooden Allen buttons are visible, but no buttons can be seen on the pants. The top of the exterior pocket welt seems to align with the middle buttonhole, which is covered by the blanket. The double-row of topstitching includes two different types of stitches. The exterior stitch (closest to the edge) is a basting stitch. The interior stitch is a backstitch. These stitches presumably extend all the way around the jacket’s edge. The interior stitch is placed close to the edge of the collar, instead of dropping about a third of the height down, as is the case with some Montgomery jackets. Interestingly, the seamtress misaligned the collar when she joined it to the neckhole, causing the base to fall below the neckhole seamline once the collar was finished. This same seamtress error is noted in two of the Anderson-style jackets. No other observations were possible.[52]

15a. This jacket, identified only by its catalog number GETT 29259, shares most of the basic characteristics of the Montgomery jackets. Regrettably, since the author could only examine it behind glass some conclusions are difficult to draw. The basic fabric matches that seen in Kingsley's jacket. The base of the collar was joined below the neckhole seamline, a mistake noted in two of the Anderson-style jackets, which makes the base of the collar fall below the seamline whan it is finished. It appears otherwise well-made with two sturdy rows of topstitching and well made buttonholes. The artifact in the 15-series of images is courtesy of the collection of the Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

There are only a few photos that clearly show soldiers wearing the Montgomery jacket. A few more might be deduced as such, based on the soldier’s location and some tenuous characteristics.

One of the best images is of an unidentified Confederate soldier, probably a veteran home from the war, wearing his Montgomery jacket with a matching pair of pants. The soldier has a small child on his left leg who obscures the view of the exterior, left breast pocket. Nonetheless, the wooden Allen buttons are plainly visible, and the general cut of the jacket and sleeves matched the Montgomery pattern. The image is without any provenance.[53]

One of the best images is of an unidentified Confederate soldier, probably a veteran home from the war, wearing his Montgomery jacket with a matching pair of pants. The soldier has a small child on his left leg who obscures the view of the exterior, left breast pocket. Nonetheless, the wooden Allen buttons are plainly visible, and the general cut of the jacket and sleeves matched the Montgomery pattern. The image is without any provenance.[53]

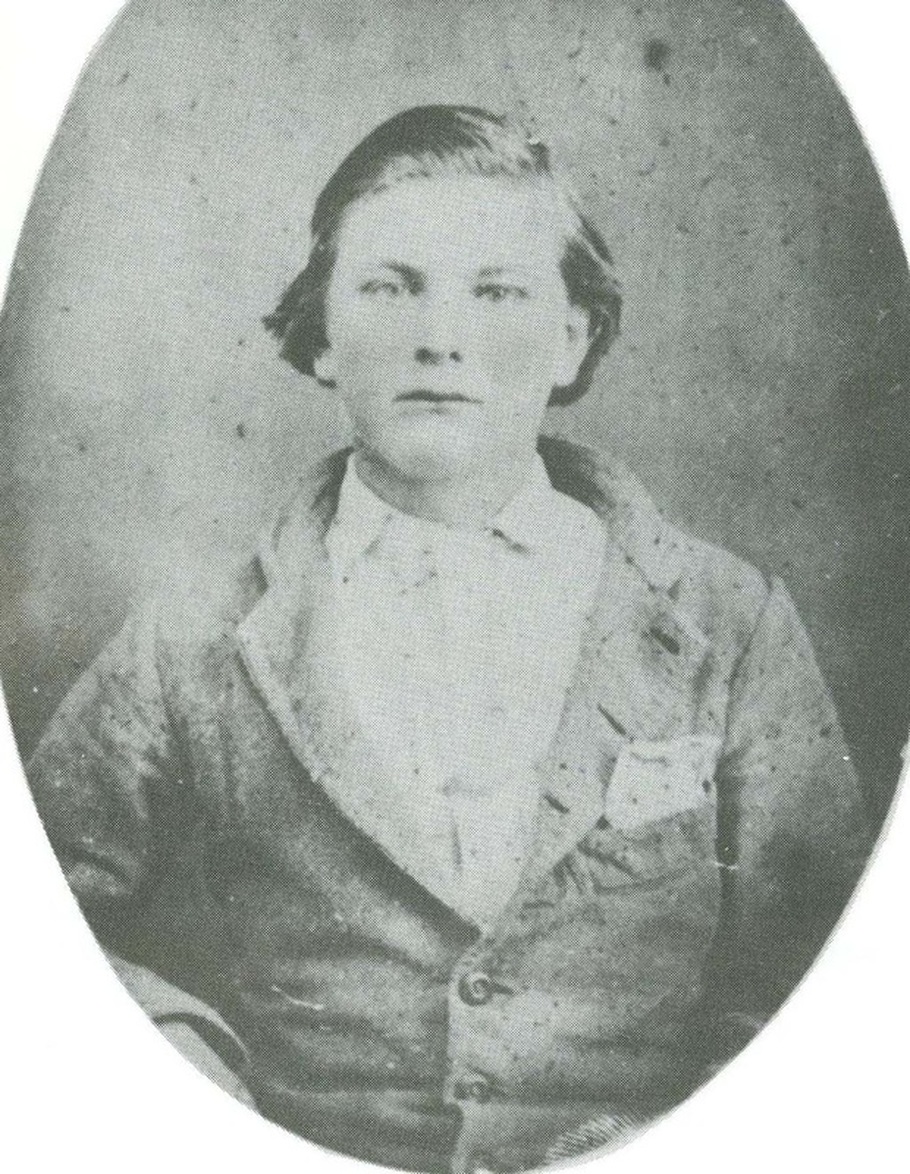

Another excellent image of the Montgomery jacket is from an image of Henry Taylor Marchman, Company A, 1st Battalion, Georgia Reserve Cavalry. Marchman was sixteen years old in 1863 when he joined the reserves. His service records are minimal, but they indicate that he served for the last two years of the war.[54] The mystery is how he managed to receive a Montgomery jacket as a member of the Georgia reserves, since the state was supposed to supply its own reserves, and Montgomery furnished clothing chiefly to Confederate troops within the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. Marchman did, however, have a Montgomery jacket, and its characteristics are distinct: seven wooden Allen buttons; a slanted exterior, left breast pocket; and, one piece sleeves.[55]

16b. Henry Taylor Marchman, a Georgia Militia cavalryman wears a Montgomery jacket. It is noteworthy that he had it, since he was not in Confederate service nor was he in the department that issued these jackets. The image is courtesy of the Washington Memorial Library, Macon, Georgia, of Brett Boyd, Marchman’s great-grandson, and of Anne Rogers.

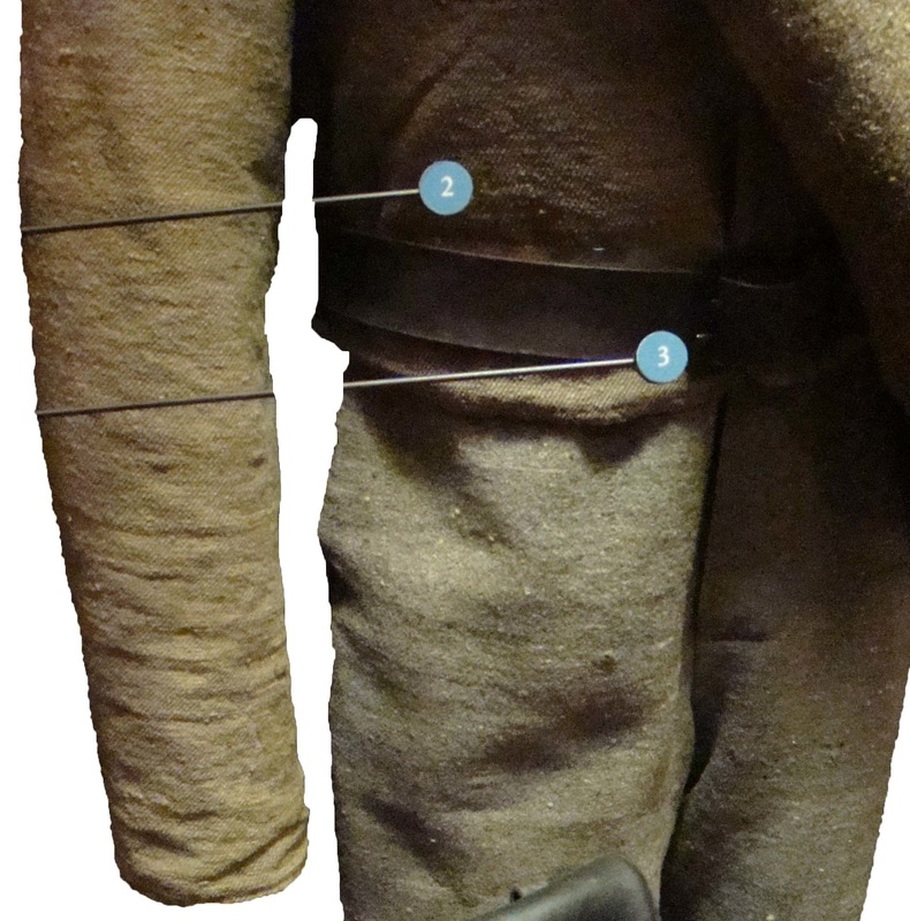

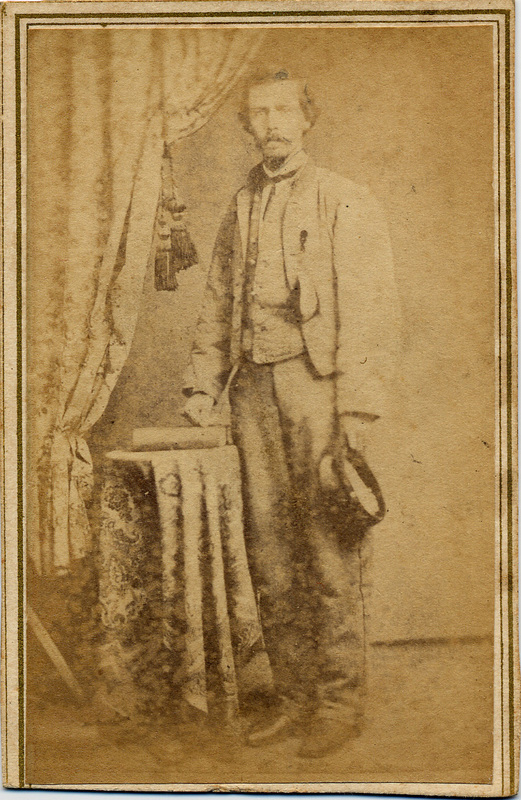

Three CDVs of Sergeant Robert W. Frazer, 5th Company, Washington Artillery, depicts him wearing a Montgomery jacket. The CDVs represent different prints of the same image taken by Anderson & Turner, 61 Camp Street, New Orleans in May 1865. The clarity of each CDV offers different insights to Frazer’s uniform. Frazer served with his battery until the end of the war, although he was mistakenly reported as having been mortally wounded at the Battle of Jonesboro.[56] He most likely received his Montgomery uniform in early 1865 while serving near Mobile. After examining the three different prints of the same image, one of which is clearer that the other, the jacket features can be discerned. The jacket has seven buttonholes (two in the middle are obscured by a tobacco pouch), somewhat pointed lapel bottoms, and the full cut sleeves so characteristic of the Montgomery jacket. Both prints are so light that the exterior, left breast pocket is not clearly visible. Furthermore, the buttons are brass, not wooden. Frazer also holds a cap with a dark-colored band. Otherwise, the basic fabric of the trousers, jacket and cap match in color and material. The untinted image show that his pants had colored edging along the side seams; pointed cuff edgings; and, a faced collar (the image is faint). These facings appear to have been red. The next two images were tinted by the photographer, who has the jacket somewhat obscured by the photographer, who tinted the facings with red ink, making the collar red, and highlighting the edging on the cuffs, vest and trouser seams. One of the tinted CDVs is available to the author in only black and white, so the color must be guessed at, but the other is a color version distinctly showing the red over tinting. Presumably, Frazer had the red trim added to his jacket after he got it from the quartermaster. The cap that Frazer hold has a dark colored band, and this too was presumably red-colored.[57]

The last Montgomery jacket image is the full length portrait of Captain Edward Brett Randolph, 7th Alabama Cavalry.[58] Randolph wears an imported Peter Tait & Company great coat over a domestic weave, enlisted soldier suit with officer collar rank. The jacket and pants fabric and color match, and the jacket has seven brass buttons. Given that Randolph probably got the great coat, jacket and pants in Montgomery (his duty station), and that the jacket has seven buttons, there is a strong possibility that the soldier suit is from the Montgomery Depot.[59]

See continuation of this study in Part III: The Pants, Caps and Hats of the Department’s Depot, and the Cadet Gray Uniforms of Mobile, Alabama. Click here to navigate to the next part...

Acknowledgements:

The author extends his thanks to numerous institutions and people for their generous cooperation and indispensable help with this study. Les Jensen’s Survey of Government Made Confederate Jackets, published in 1989, provided the first study of the “Alabama” (Anderson-style) jackets. Harold S. Wilson’s Confederate Industry provided an understanding for clothing bureau operations. Tom Arliskas’s Cadet Gray and Butternut Brown provided invaluable insights on the uniforms. Numerous institutions and individuals have shared their collections, insights, and valuable time with me to make the study possible. These include The Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, Chief Curator, Robert Hancock; Alabama Confederate Memorial Park, Marbury, Alabama, Director Bill Rambo; Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama, Bob Bradley and Dr. Kerr; Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Executive Director Ray Richey; Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana, Director Pat Ricci; Washington Artillery of New Orleans website and Glen C. Cangelosi collection; Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana, Chief Curator Wayne Phillips; Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia, Curator Heather Beattie; Museum of Southern History, Houston Baptist University, Houston, Texas, Curator Maggie Brown; General Sweeny’s Civil War Museum, Republic, Missouri, Dr. Tom Sweeney and Joseph Furtak; Wilson Creek National Battlefield, Republic, Missouri, Curators Deborah Wood and Alan Chilton; Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Curator Paul Shevchuk; Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, Curator Margaret Vining; South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina, Curator Joe Long; Neill Rose, Camden, South Carolina; Alan Hoeweller collection, Cincinnati, Ohio; Samuel P. Higginbotham II collection, Orange, Virginia; Lawrence T. Jones III, Confederate Calendar, Austin, Texas; Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III collection, Dallas, Texas; Old Courthouse Museum, Vicksburg, Mississippi, Gordon A. Cotton and Jeff T. Giambrone; J.S. Mosby Antiques & Artifacts, Orange, Virginia, Stephen W. Sylvia; Historian Mike Bailey, Fort Morgan Historic Site, Gulf Shores, Alabama; Collecting the Confederate Soldier, Jim Osborn, Rockywood Productions, Inc., Denver, Colorado, 1996, Richard Todd collection; Archivist Vicki Betts, University of Texas, Tyler, online newspapers; Washington Memorial Library, Macon, Georgia, Brett Boyd and Anne Rogers; Military Images, Editor Ron Coddington, Arlington, Virginia; North South Trader Civil War, Publisher Steve Sylvia, Orange, Virginia; the Pink Palace Museum, Memphis, Tennessee; and, an anonymous private collection by wishes of the owner.

Copyright:

All photos are copyrighted to Adolphus Confederate Uniforms. Although the artifacts are credited to different institutions, the images themselves are the property of the website and may not be reproduced without the author’s consent.

Bibliography:

[42] Arliskas, Thomas M., Cadet Gray and Butternut Brown: Notes on Confederate Uniforms, Thomas Publications, Gettysburg, PA, 2006, p. 29, note 15, p. 100, from a Northern newspaper, Ottawa [Illinois] Free Trader, March 8, 1862, soldier's letter, described what may have been an in-between, partly faded color as "brindle," noting that the Confederates at Fort Donelson had "uniforms of all shades of colors, gray, brindle, and butternut, the last predominating." Brindle may have described the peculiar Confederate unintentional practice of mixing dark weft yarns with lighter that gave the illusion of stripes. The dictionary defines brindle as "tawny or grayish interspersed with streaks of darker color."

[43] Observations made from the video, Collecting the Confederate Soldier, Jim Osborn, Rockywood Productions, Inc., Denver, Colorado, 1996. The Kingsley jacket was part of the West Point Museum collection prior to Curator Richard Todd’s retirement, at which point the museum gave Todd the jacket. The jacket is now in an unknown private collection, and all attempts to reach the video publisher, Jim Osborn, have failed, and his company appears to be defunct.

[44] Artifact in the collection of the Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Author examined the jacket on 17 December 2010.

[45] Artifact in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; accession number 1980.0399.0921, and old catalog number U081. Author examined the jacket in May 1996, and 16 December 2010.

[46] CSRs Confederate, M258, Roll 58, Joseph Stone; CSRs Alabama, M311, Roll 348, J.N. Stone; CSRs Mississippi, M269, Roll 72, Joseph N. Stone.

[47] Artifact in the collection of Sam Higginbotham, Orange, Virginia. Author examined the jacket on 17 October 2013. Furthermore, Nancy Dearing Rossbacher not only brought the jacket to my attention, but provided a detailed history of the Stone brothers’ Confederate service in her article The Stone Brothers of Natchez, North South Trader’s Civil War magazine, Good Printers, Inc, Bridgewater, Virginia, Volume 33, No. 4, 2008, pp. 38-45, and 60-61.

[48] CSRs Missouri, M322, Roll 34, George J. Mook and George Mook.

[49] Artifact in the collection of the National Battlefield Park, Wilson’s Creek, Missouri. Author examined the jacket on 31 October 1998 while it was part of Dr. Sweeney’s collection in Republic, Missouri; and, again in August 2011 at Wilson’s Creek.

[50] Cooper’s sparse records give conflicting dates for his death, his middle name, and his command affiliation. The records all confirm that he died in May 1865, Raleigh, North Carolina, and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery; and, that he served with a South Carolina command. The South Carolina Confederate Relic Room provided most of the data on Cooper. The CSRs were inconclusive.

[51] Artifact in the collection of the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina. Observations made from photographs provided by Neill Rose, Camden, South Carolina.

[52] Artifact in the collection of the Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Author examined the jacket on 17 December 2010.

[53] CDV in the collection of Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III photograph collection, Dallas, Texas.

[54] CSRs Georgia, M266, Roll 8, H.T. Marchman.

[55] Image in the collection of the Washington Memorial Library, Macon, Georgia, courtesy of Brett Boyd, Marchman’s great-grandson, and Anne Rogers.

[56] CSRs Louisiana, M320, Roll 65, Robert W. Frazer, Co. 5.

[57] From three versions of the same CDV of Robert W. Frazer: one is courtesy of the Glen C. Cangelosi collection and the Washington Artillery of New Orleans website, http://www.washingtonartillery.com; the second of J.S. Mosby Antiques & Artifacts, reference Civil War Collector’s Price Guide 11th Edition, p. 234; and, the third of Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana, Catalog # 001.005.570.

[58] CSRs Alabama, M311, Roll 26, E.B. Randolph.

[59] ADAH photo archives, Captain Edward Brett Randolph image.

Acknowledgements:

The author extends his thanks to numerous institutions and people for their generous cooperation and indispensable help with this study. Les Jensen’s Survey of Government Made Confederate Jackets, published in 1989, provided the first study of the “Alabama” (Anderson-style) jackets. Harold S. Wilson’s Confederate Industry provided an understanding for clothing bureau operations. Tom Arliskas’s Cadet Gray and Butternut Brown provided invaluable insights on the uniforms. Numerous institutions and individuals have shared their collections, insights, and valuable time with me to make the study possible. These include The Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, Chief Curator, Robert Hancock; Alabama Confederate Memorial Park, Marbury, Alabama, Director Bill Rambo; Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama, Bob Bradley and Dr. Kerr; Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Executive Director Ray Richey; Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana, Director Pat Ricci; Washington Artillery of New Orleans website and Glen C. Cangelosi collection; Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana, Chief Curator Wayne Phillips; Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia, Curator Heather Beattie; Museum of Southern History, Houston Baptist University, Houston, Texas, Curator Maggie Brown; General Sweeny’s Civil War Museum, Republic, Missouri, Dr. Tom Sweeney and Joseph Furtak; Wilson Creek National Battlefield, Republic, Missouri, Curators Deborah Wood and Alan Chilton; Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Curator Paul Shevchuk; Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, Curator Margaret Vining; South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina, Curator Joe Long; Neill Rose, Camden, South Carolina; Alan Hoeweller collection, Cincinnati, Ohio; Samuel P. Higginbotham II collection, Orange, Virginia; Lawrence T. Jones III, Confederate Calendar, Austin, Texas; Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III collection, Dallas, Texas; Old Courthouse Museum, Vicksburg, Mississippi, Gordon A. Cotton and Jeff T. Giambrone; J.S. Mosby Antiques & Artifacts, Orange, Virginia, Stephen W. Sylvia; Historian Mike Bailey, Fort Morgan Historic Site, Gulf Shores, Alabama; Collecting the Confederate Soldier, Jim Osborn, Rockywood Productions, Inc., Denver, Colorado, 1996, Richard Todd collection; Archivist Vicki Betts, University of Texas, Tyler, online newspapers; Washington Memorial Library, Macon, Georgia, Brett Boyd and Anne Rogers; Military Images, Editor Ron Coddington, Arlington, Virginia; North South Trader Civil War, Publisher Steve Sylvia, Orange, Virginia; the Pink Palace Museum, Memphis, Tennessee; and, an anonymous private collection by wishes of the owner.

Copyright:

All photos are copyrighted to Adolphus Confederate Uniforms. Although the artifacts are credited to different institutions, the images themselves are the property of the website and may not be reproduced without the author’s consent.

Bibliography:

[42] Arliskas, Thomas M., Cadet Gray and Butternut Brown: Notes on Confederate Uniforms, Thomas Publications, Gettysburg, PA, 2006, p. 29, note 15, p. 100, from a Northern newspaper, Ottawa [Illinois] Free Trader, March 8, 1862, soldier's letter, described what may have been an in-between, partly faded color as "brindle," noting that the Confederates at Fort Donelson had "uniforms of all shades of colors, gray, brindle, and butternut, the last predominating." Brindle may have described the peculiar Confederate unintentional practice of mixing dark weft yarns with lighter that gave the illusion of stripes. The dictionary defines brindle as "tawny or grayish interspersed with streaks of darker color."

[43] Observations made from the video, Collecting the Confederate Soldier, Jim Osborn, Rockywood Productions, Inc., Denver, Colorado, 1996. The Kingsley jacket was part of the West Point Museum collection prior to Curator Richard Todd’s retirement, at which point the museum gave Todd the jacket. The jacket is now in an unknown private collection, and all attempts to reach the video publisher, Jim Osborn, have failed, and his company appears to be defunct.

[44] Artifact in the collection of the Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Author examined the jacket on 17 December 2010.

[45] Artifact in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; accession number 1980.0399.0921, and old catalog number U081. Author examined the jacket in May 1996, and 16 December 2010.

[46] CSRs Confederate, M258, Roll 58, Joseph Stone; CSRs Alabama, M311, Roll 348, J.N. Stone; CSRs Mississippi, M269, Roll 72, Joseph N. Stone.

[47] Artifact in the collection of Sam Higginbotham, Orange, Virginia. Author examined the jacket on 17 October 2013. Furthermore, Nancy Dearing Rossbacher not only brought the jacket to my attention, but provided a detailed history of the Stone brothers’ Confederate service in her article The Stone Brothers of Natchez, North South Trader’s Civil War magazine, Good Printers, Inc, Bridgewater, Virginia, Volume 33, No. 4, 2008, pp. 38-45, and 60-61.

[48] CSRs Missouri, M322, Roll 34, George J. Mook and George Mook.

[49] Artifact in the collection of the National Battlefield Park, Wilson’s Creek, Missouri. Author examined the jacket on 31 October 1998 while it was part of Dr. Sweeney’s collection in Republic, Missouri; and, again in August 2011 at Wilson’s Creek.

[50] Cooper’s sparse records give conflicting dates for his death, his middle name, and his command affiliation. The records all confirm that he died in May 1865, Raleigh, North Carolina, and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery; and, that he served with a South Carolina command. The South Carolina Confederate Relic Room provided most of the data on Cooper. The CSRs were inconclusive.

[51] Artifact in the collection of the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina. Observations made from photographs provided by Neill Rose, Camden, South Carolina.

[52] Artifact in the collection of the Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Author examined the jacket on 17 December 2010.

[53] CDV in the collection of Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III photograph collection, Dallas, Texas.

[54] CSRs Georgia, M266, Roll 8, H.T. Marchman.

[55] Image in the collection of the Washington Memorial Library, Macon, Georgia, courtesy of Brett Boyd, Marchman’s great-grandson, and Anne Rogers.

[56] CSRs Louisiana, M320, Roll 65, Robert W. Frazer, Co. 5.

[57] From three versions of the same CDV of Robert W. Frazer: one is courtesy of the Glen C. Cangelosi collection and the Washington Artillery of New Orleans website, http://www.washingtonartillery.com; the second of J.S. Mosby Antiques & Artifacts, reference Civil War Collector’s Price Guide 11th Edition, p. 234; and, the third of Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana, Catalog # 001.005.570.

[58] CSRs Alabama, M311, Roll 26, E.B. Randolph.

[59] ADAH photo archives, Captain Edward Brett Randolph image.