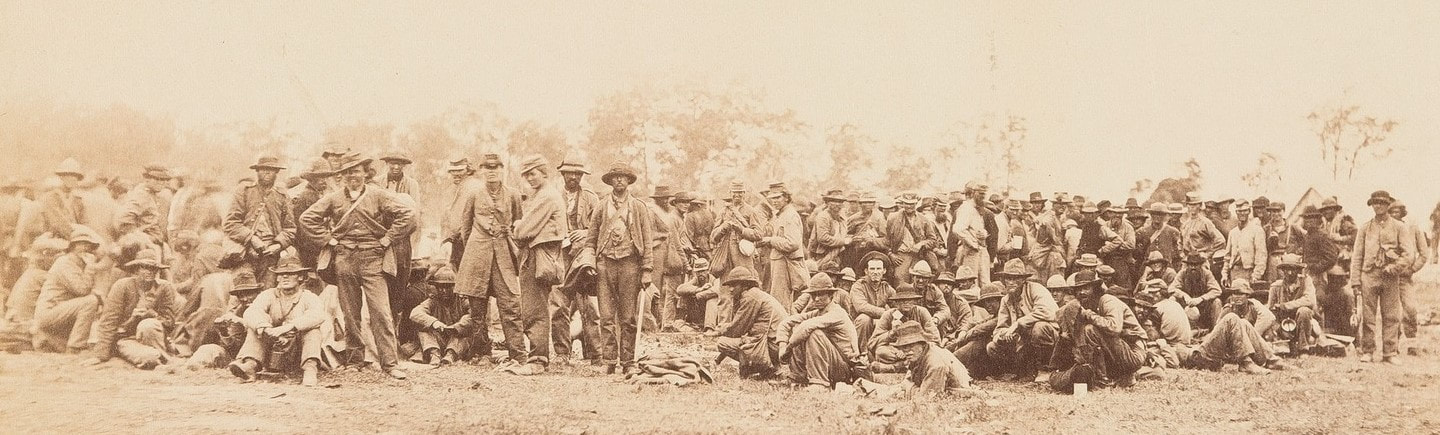

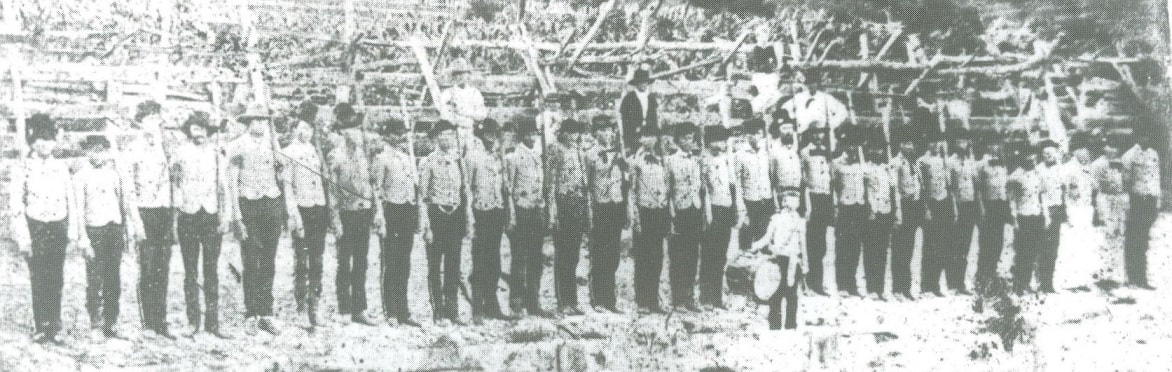

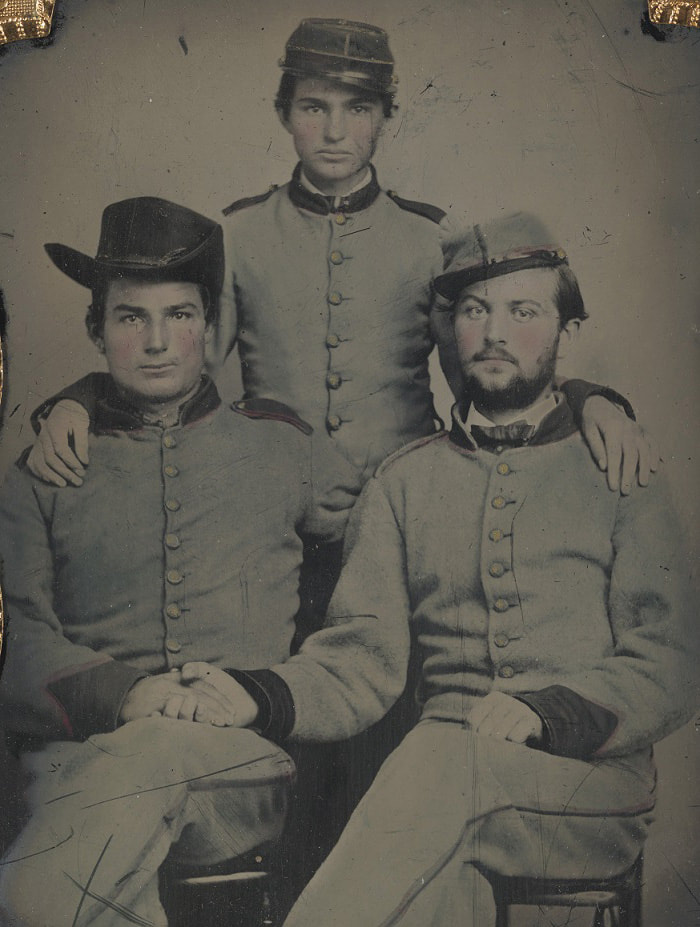

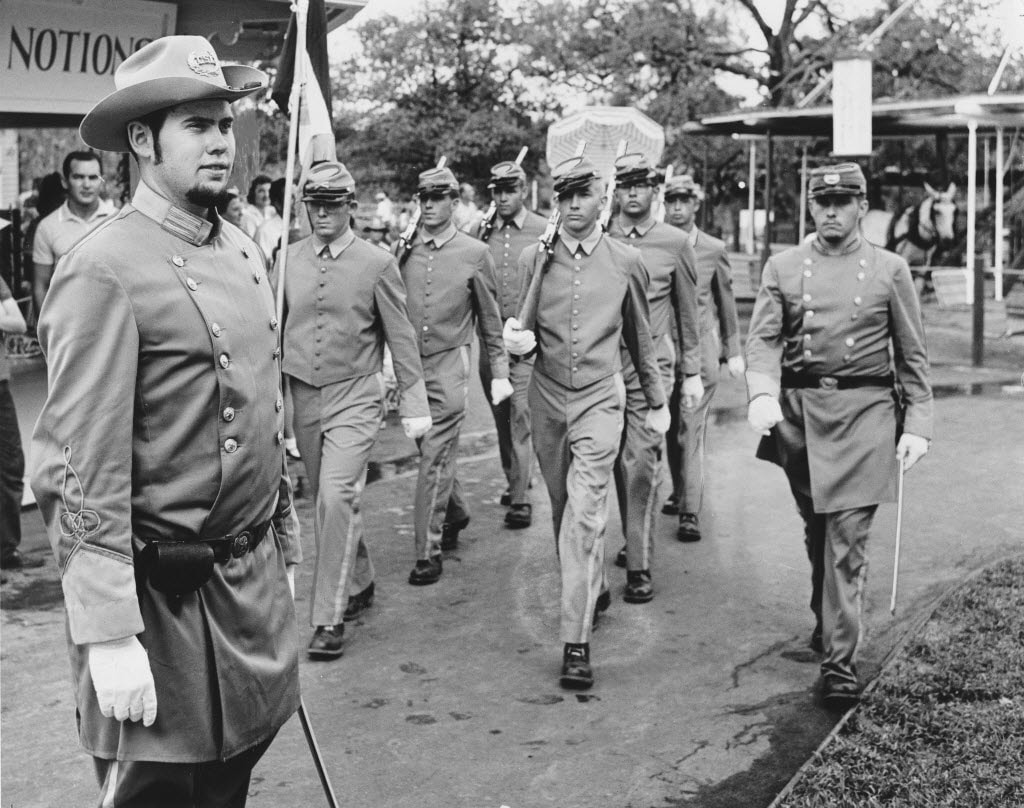

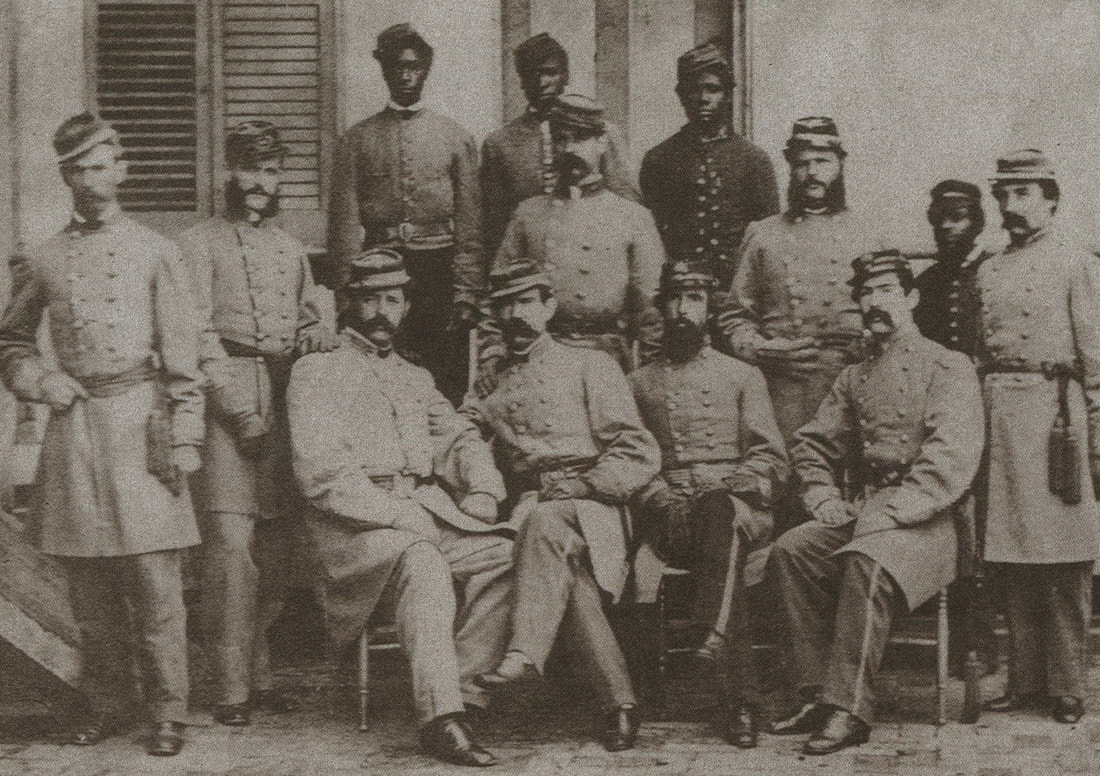

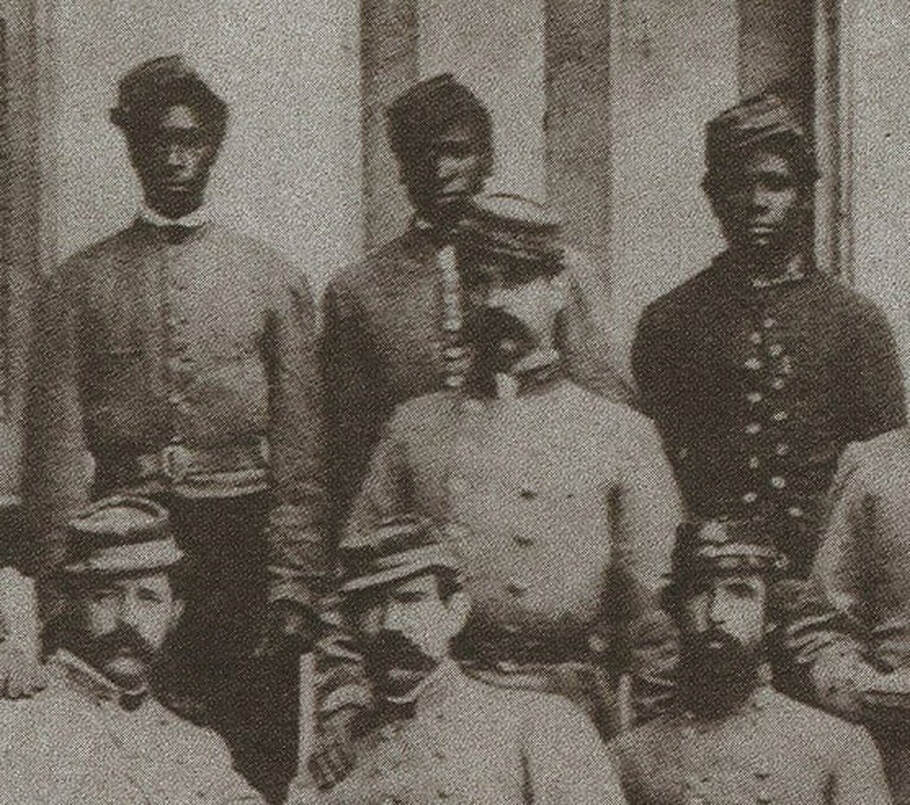

076: General Randall Slaughter’s staff in Galveston, Texas, 1864. The officers and the enlisted servants wear the Confederate chasseur cap. Given the image’s provenance, the uniforms and caps are probably from the Houston Depot. Image courtesy of the Lawrence T. Jones, III, Confederate Calendar Works, Austin, Texas, 2003, William A. Turner collection.

The Quintessential Confederate Cap, Part IV: Trans-Mississippi Caps, Cap Covers, General Usage and Legacy

Fred Adolphus, 29 June 2023

Click this link to navigate to Part III of this study...

Trans-Mississippi Caps

No depot caps identified to the Trans-Mississippi region appear to have survived. From this theater of the war, there are only reports, descriptions and photos to study. The preponderance of the evidence indicates that during the winter of 1862-63, the Monroe, Little Rock, Houston and San Antonio Depots used the prolific quantities of imported, dark, blue-gray kersey cloth to make and issue Confederate gray caps. Enough imported Confederate gray cloth continued to arrive to enable Trans-Mississippi quartermasters to continue making caps of this type. Quartermaster records substantiate this. For instance, from November 1862 to May 1863, the 3rd Texas Infantry, 33rd Texas Cavalry and 8th Texas Cavalry Battalion drew gray cloth caps from San Antonio.[97] During the winter of 1862-63, the 8th Texas Field Battery also drew gray caps, presumably from San Antonio, as well.[98] Likewise, the Monroe and Shreveport Depot operation must have made a number of cadet gray caps, based upon the availability of this cloth. Ironically, the only good description of caps made at Monroe refers to those made from Huntsville Penitentiary, white kersey. Accordingly, the Monroe quartermaster sent a supply of white kersey jackets, pants and caps to the 24th Texas Dismounted Cavalry at Arkansas Post in November 1862.[99]

Records about the Little Rock Depot’s caps are also sparse. The one cap issued from Little Rock, that has survived the war, was not even a bonafide Trans-Mississippi cap: it was from the Columbus Depot in Georgia.[100] Nevertheless, the Little Rock quartermaster undoubtedly made and issued caps from undyed, Huntsville kersey during 1862. An Arkansas soldier stationed near Little Rock, W.H.H. Shibley, wrote to his parents on 19 October 1862, “I have drawn a cap as my hat was worn out. John Samuel’s hat is very good yet [referring to his brother].”[101] The Shibley brothers served in Company G, 22nd Arkansas Infantry. Shortly thereafter, in November 1862, the Little Rock Depot received enough imported, cadet gray cloth to clothe 30,000 officers and men.[102] Such a supply of cloth would have enabled the Little Rock Depot to make thousands of cadet gray caps from the manufacturing scrap alone. Little Rock quartermaster records, dating from December 1862 to September 1863, indicate the depot-issued soldier suits consisted of jackets, caps and pants.[103] Most of these articles would have been of cadet gray kersey, and to a lesser extent, of white Huntsville goods.

Houston Depot Caps

Unfortunately, no original cap survives from the Houston Depot. Fortunately, complete descriptions of the Houston Depot caps are available, as well as some photographs of Houston caps.

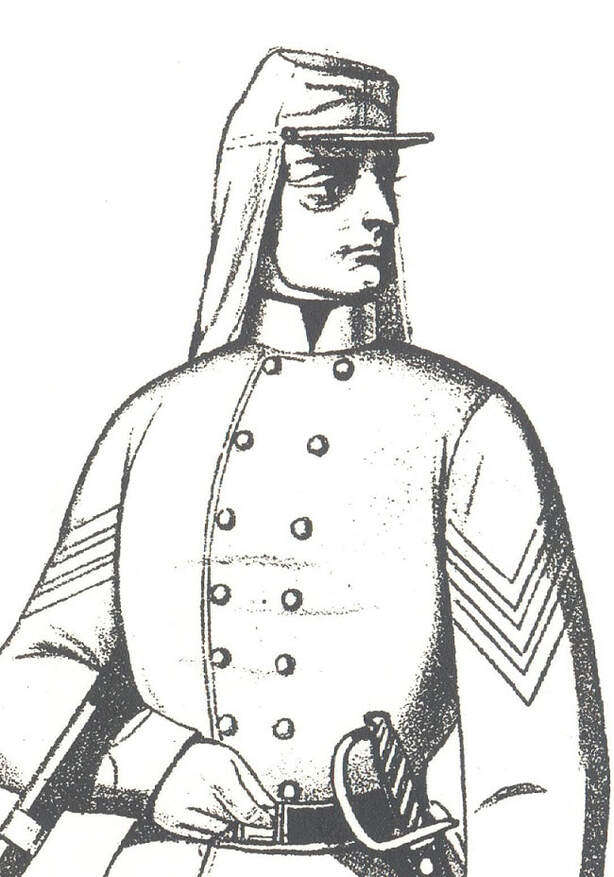

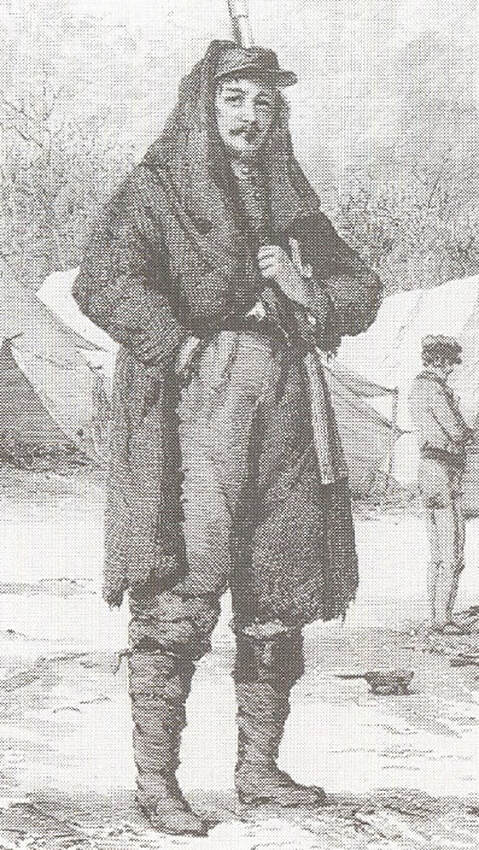

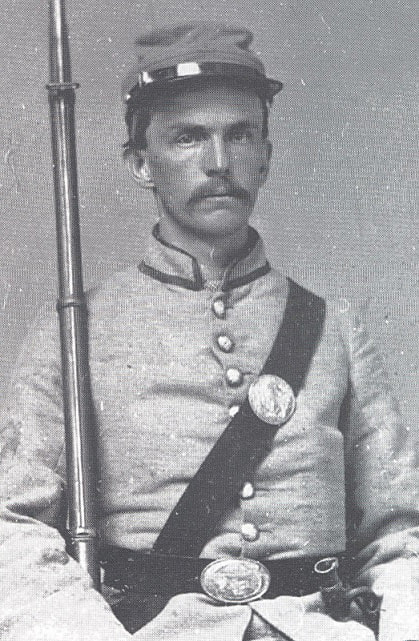

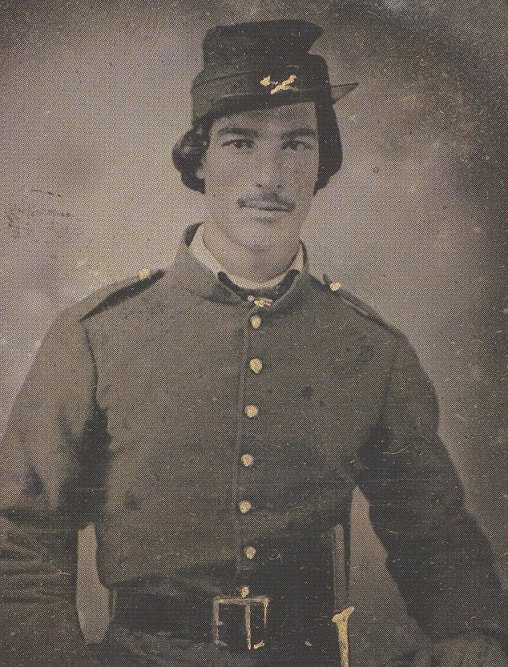

The section on cap manufacture touched briefly on the Houston cap. To recapitulate, it was an 1861 regulation cap with a cadet gray crown and sides, and a colored band in the branch-of-service color of red, blue or yellow. It had a glazed leather visor and an unbleached osnaburg or calico lining. Captain E.C. Wharton, Chief of the Texas Clothing Bureau, CSA, neglected to mention anything about the cap’s chinstrap, sweatband or buttons, or whether the cap was in the style of the “French kepi” (i.e. chasseur).[104] However, images of soldiers believed to be wearing the Houston cap show a distinct chasseur pattern. Wharton also never specifically mentioned whether he used light or dark blue for the infantry bands, but judging from an image of a soldier wearing one of his caps, it appears that he used light blue kersey. This makes sense, because he would have had scrap left over from making light blue enlisted trousers.

Additional documents confirm that the Houston Clothing Depot made the caps that Wharton described in December 1863. On October 11, 1863, the depot reported manufacturing caps from the scraps of cadet gray cloth left from making jackets and trousers. The leather visors were made in the government shoe shop.[105] An expenditure report from November 1863 records the following materials having been used in making caps: grey cloth [cadet gray]; bleached domestic; yellow calico; red flannel; blue velvet; flax thread; penitentiary spool cotton thread; cap fronts; and, pasteboard.[106] Additional records from 1863 show that the depot also expended yellow flannel, and red, blue and yellow fine cloth in making uniforms. While not explicitly stated, Wharton probably used scrap from the manufacture of coarse, light blue kersey, enlisted trousers for trim cloth, as well. Available records indicate that Wharton made caps according to the 1861 regulations with cadet gray sides and crowns and colored bands (for the three principal branches). During October and November 1863, the depot had an inventory of 874 cadet gray caps with colored bands: 253 were cavalry yellow (29%); 475 were infantry blue (54%); and, 146 were artillery red (17%).[107] This data suggests that Wharton was making caps at the approximate ratios of the three branches of service in Texas, and that all of the caps that he manufactured were cadet gray caps with colored bands and leather visors. The records also affirm that the Houston Depot made neither plain gray caps nor 1862 regulation caps.

Trans-Mississippi Caps

No depot caps identified to the Trans-Mississippi region appear to have survived. From this theater of the war, there are only reports, descriptions and photos to study. The preponderance of the evidence indicates that during the winter of 1862-63, the Monroe, Little Rock, Houston and San Antonio Depots used the prolific quantities of imported, dark, blue-gray kersey cloth to make and issue Confederate gray caps. Enough imported Confederate gray cloth continued to arrive to enable Trans-Mississippi quartermasters to continue making caps of this type. Quartermaster records substantiate this. For instance, from November 1862 to May 1863, the 3rd Texas Infantry, 33rd Texas Cavalry and 8th Texas Cavalry Battalion drew gray cloth caps from San Antonio.[97] During the winter of 1862-63, the 8th Texas Field Battery also drew gray caps, presumably from San Antonio, as well.[98] Likewise, the Monroe and Shreveport Depot operation must have made a number of cadet gray caps, based upon the availability of this cloth. Ironically, the only good description of caps made at Monroe refers to those made from Huntsville Penitentiary, white kersey. Accordingly, the Monroe quartermaster sent a supply of white kersey jackets, pants and caps to the 24th Texas Dismounted Cavalry at Arkansas Post in November 1862.[99]

Records about the Little Rock Depot’s caps are also sparse. The one cap issued from Little Rock, that has survived the war, was not even a bonafide Trans-Mississippi cap: it was from the Columbus Depot in Georgia.[100] Nevertheless, the Little Rock quartermaster undoubtedly made and issued caps from undyed, Huntsville kersey during 1862. An Arkansas soldier stationed near Little Rock, W.H.H. Shibley, wrote to his parents on 19 October 1862, “I have drawn a cap as my hat was worn out. John Samuel’s hat is very good yet [referring to his brother].”[101] The Shibley brothers served in Company G, 22nd Arkansas Infantry. Shortly thereafter, in November 1862, the Little Rock Depot received enough imported, cadet gray cloth to clothe 30,000 officers and men.[102] Such a supply of cloth would have enabled the Little Rock Depot to make thousands of cadet gray caps from the manufacturing scrap alone. Little Rock quartermaster records, dating from December 1862 to September 1863, indicate the depot-issued soldier suits consisted of jackets, caps and pants.[103] Most of these articles would have been of cadet gray kersey, and to a lesser extent, of white Huntsville goods.

Houston Depot Caps

Unfortunately, no original cap survives from the Houston Depot. Fortunately, complete descriptions of the Houston Depot caps are available, as well as some photographs of Houston caps.

The section on cap manufacture touched briefly on the Houston cap. To recapitulate, it was an 1861 regulation cap with a cadet gray crown and sides, and a colored band in the branch-of-service color of red, blue or yellow. It had a glazed leather visor and an unbleached osnaburg or calico lining. Captain E.C. Wharton, Chief of the Texas Clothing Bureau, CSA, neglected to mention anything about the cap’s chinstrap, sweatband or buttons, or whether the cap was in the style of the “French kepi” (i.e. chasseur).[104] However, images of soldiers believed to be wearing the Houston cap show a distinct chasseur pattern. Wharton also never specifically mentioned whether he used light or dark blue for the infantry bands, but judging from an image of a soldier wearing one of his caps, it appears that he used light blue kersey. This makes sense, because he would have had scrap left over from making light blue enlisted trousers.

Additional documents confirm that the Houston Clothing Depot made the caps that Wharton described in December 1863. On October 11, 1863, the depot reported manufacturing caps from the scraps of cadet gray cloth left from making jackets and trousers. The leather visors were made in the government shoe shop.[105] An expenditure report from November 1863 records the following materials having been used in making caps: grey cloth [cadet gray]; bleached domestic; yellow calico; red flannel; blue velvet; flax thread; penitentiary spool cotton thread; cap fronts; and, pasteboard.[106] Additional records from 1863 show that the depot also expended yellow flannel, and red, blue and yellow fine cloth in making uniforms. While not explicitly stated, Wharton probably used scrap from the manufacture of coarse, light blue kersey, enlisted trousers for trim cloth, as well. Available records indicate that Wharton made caps according to the 1861 regulations with cadet gray sides and crowns and colored bands (for the three principal branches). During October and November 1863, the depot had an inventory of 874 cadet gray caps with colored bands: 253 were cavalry yellow (29%); 475 were infantry blue (54%); and, 146 were artillery red (17%).[107] This data suggests that Wharton was making caps at the approximate ratios of the three branches of service in Texas, and that all of the caps that he manufactured were cadet gray caps with colored bands and leather visors. The records also affirm that the Houston Depot made neither plain gray caps nor 1862 regulation caps.

077: This souvenir cap taken by a New York soldier was reportedly brought home from Virginia. While the souvenir cap may not be a Houston Depot cap, it is representative of the caps made in Houston. In the absence of a surviving original, it serves to illustrate the Confederate gray cap with a colored band that Wharton's quartermaster records describe.

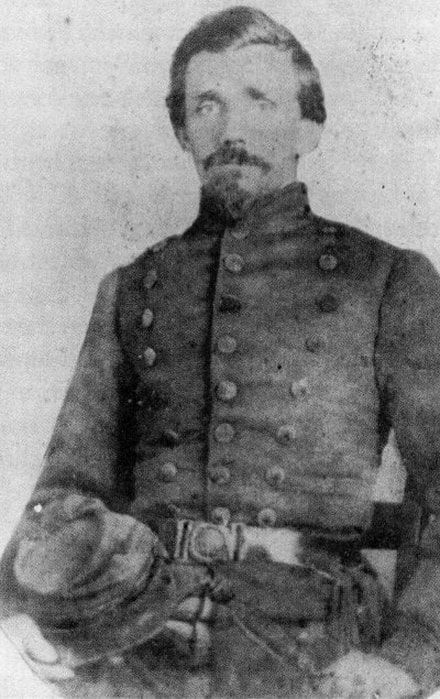

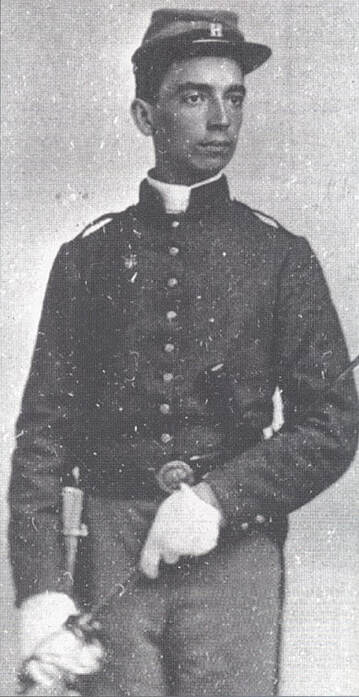

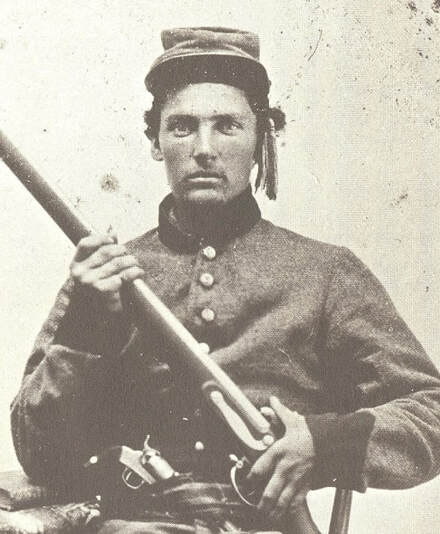

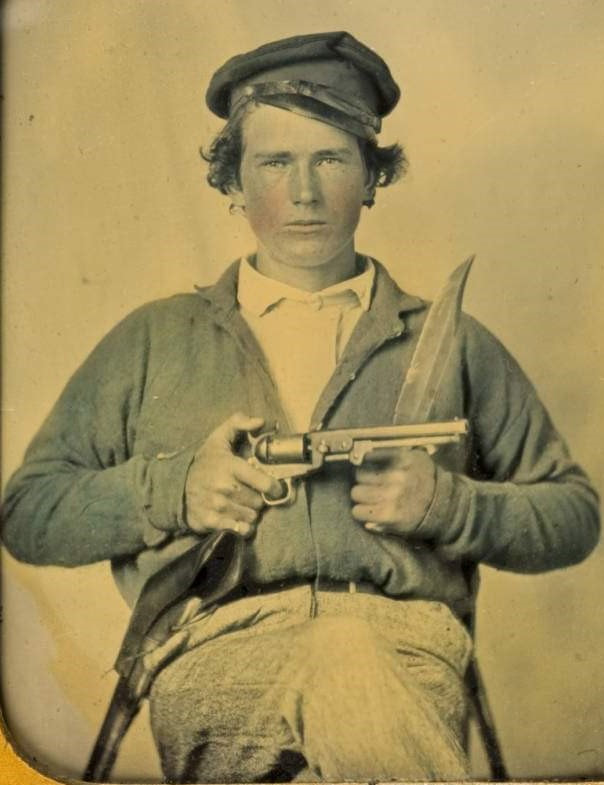

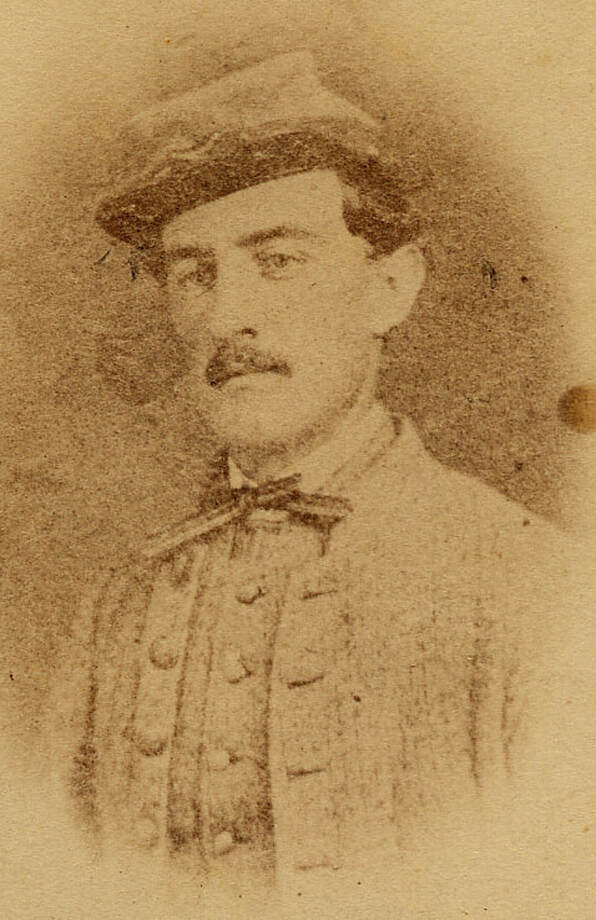

078a: Private Lloyd Walter Surghnor’s image provides a rare view of a Trans-Mississippi Depot infantry cap. Surghnor served in Company A, 16th Texas Infantry, and his cap was probably from the Houston Depot. Interestingly, the cap has slightly highly sides than the typical Confederate chasseur cap, adding to both the height and comfort of wearing it. The image has been flipped horizontally to show the correct positioning of the jacket buttons. Image courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

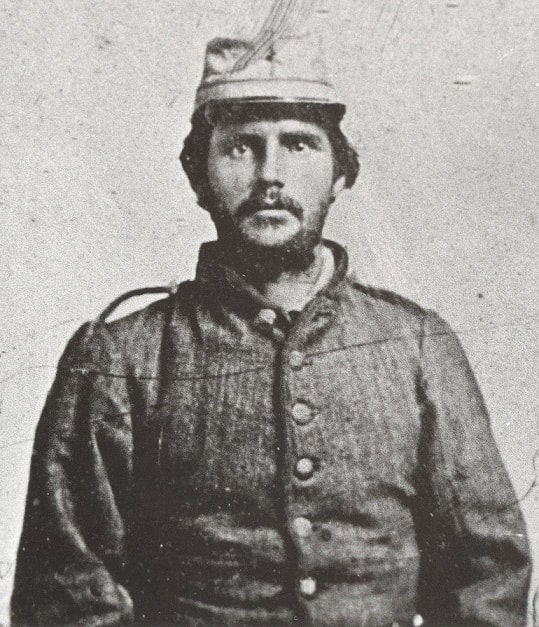

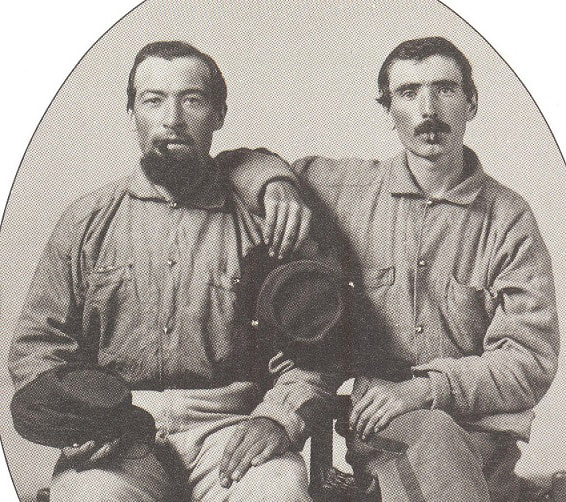

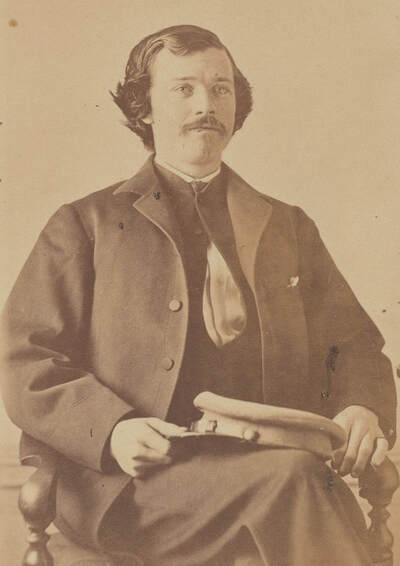

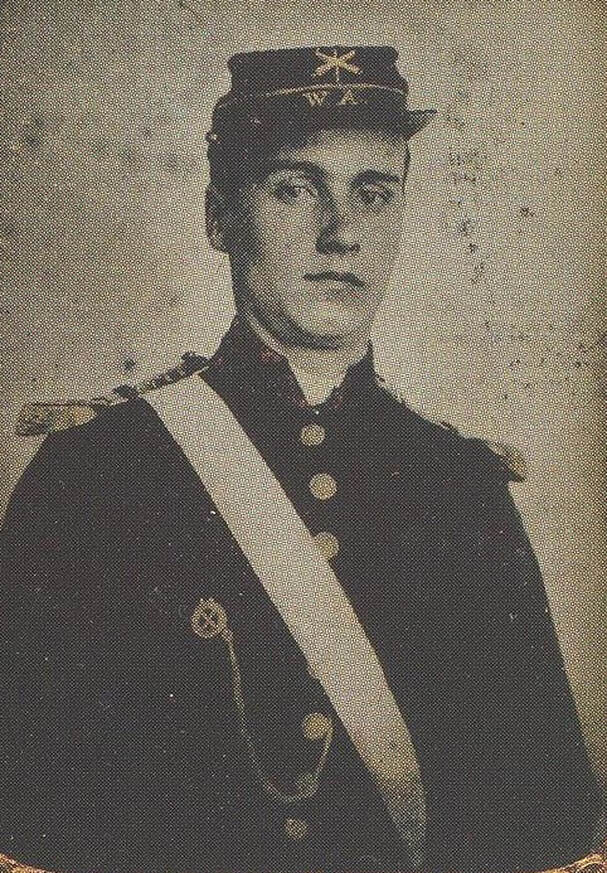

078b: An unidentified soldier of the 2nd Texas Cavalry wears a chasseur cap with a colored band. The band comes to a raised point in the front, as observed in several early-war militia caps. Since the color yellow sometimes showed as black in period photography, it cannot be determined which of the two colors the band was. The image has been flipped horizontally to show the correct position of jacket buttons. Image courtesy of Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III collection, Dallas, Texas.

078g: This cropped image of General Slaughter's staff in Galveston includes his servants, who may be wearing Houston Depot uniforms, in which case the caps would most likely have been made in Houston, as well. The soldier on standing to the right has a cap with a colored band. In typical Confederate fashion, the black, enlisted soldiers wear their caps cocked rakishly to the right. Image courtesy of the Lawrence T. Jones, III, Confederate Calendar Works, Austin, Texas, 2003, William A. Turner collection.

Havelocks, Oil Covers and Glazed Caps

Although not widespread, the story of the Confederate cap is not complete without mentioning the havelock, oil cover and “glazed” enamel cloth cap. The havelock was codified in the Confederate uniform regulations, but rarely saw service, even in the opening months of the war. The lightweight, white cotton, havelock was intended to protect the wearer’s neck and ears from sunburn and provide some shade around his head. Its top section took the form of the body of the cap, fitting over it. Attached to the base of the havelock top was a generous cape that flaired out from the head and extended to the shoulders or even lower. The havelock might fasten too the cap on the chinstrap buttons, or it might fit over the visor with a special sleeve, or it could be tied in place with a drawstring. While havelock was theoretically practical, Johnny Reb preferred the shade from a soft hat, and eschewed the havelock entirely. Nonetheless, the Seamless Garment Company’s havelock was enthusiastically described by the Daily Advocate of Baton Rouge, Louisiana on 29 May 1861, to include its dimensions, as follows:[108]

“Havelocks. — The best article of soldiers’ clothing ever invented is the one named after Gen. Havelock, from the circumstance that he introduced it into the English army in India. When made of suitable materials, it is a protection against heat, cold and rain. It can be furnished at so low a price that every one can be carried in the pocket, when not wanted on the head, and when required can be adjusted upon the fatigue cap in less than a minute… made of good twilled cotton,… stout white linen,… and of good white flannel,… For wet weather they may be made of water-proof fabrics, and for winter old gray flannel or thicker cloth, as they probably will be by the Seamless Garment Company.

“There is a crown piece five inches across. The head piece is three and a half inches wide at each end, and five inches in the centre, stitched to the crown, with the ends stitched together in front, with a visor two inches deep in the center and eleven inches in extreme length, where it is stitched to the head piece. Then a cape six and a half inches deep, cut circular, is stitched to the back of the head piece, extending from one point to the other of the visor. Over this seam inside is stitched a tape easing for a double draw string to pucker it to suit different sized heads. The visor is made double, and open inside, so that the leather visor of a common fatigue cap can be inserted, as the Havelock is thrown over it, which can be done while on the march almost instantly. The inner edge of the under part of the visor is hemmed, and the front edge stitched, and the outer edge of the cape hemmed.”

Although not widespread, the story of the Confederate cap is not complete without mentioning the havelock, oil cover and “glazed” enamel cloth cap. The havelock was codified in the Confederate uniform regulations, but rarely saw service, even in the opening months of the war. The lightweight, white cotton, havelock was intended to protect the wearer’s neck and ears from sunburn and provide some shade around his head. Its top section took the form of the body of the cap, fitting over it. Attached to the base of the havelock top was a generous cape that flaired out from the head and extended to the shoulders or even lower. The havelock might fasten too the cap on the chinstrap buttons, or it might fit over the visor with a special sleeve, or it could be tied in place with a drawstring. While havelock was theoretically practical, Johnny Reb preferred the shade from a soft hat, and eschewed the havelock entirely. Nonetheless, the Seamless Garment Company’s havelock was enthusiastically described by the Daily Advocate of Baton Rouge, Louisiana on 29 May 1861, to include its dimensions, as follows:[108]

“Havelocks. — The best article of soldiers’ clothing ever invented is the one named after Gen. Havelock, from the circumstance that he introduced it into the English army in India. When made of suitable materials, it is a protection against heat, cold and rain. It can be furnished at so low a price that every one can be carried in the pocket, when not wanted on the head, and when required can be adjusted upon the fatigue cap in less than a minute… made of good twilled cotton,… stout white linen,… and of good white flannel,… For wet weather they may be made of water-proof fabrics, and for winter old gray flannel or thicker cloth, as they probably will be by the Seamless Garment Company.

“There is a crown piece five inches across. The head piece is three and a half inches wide at each end, and five inches in the centre, stitched to the crown, with the ends stitched together in front, with a visor two inches deep in the center and eleven inches in extreme length, where it is stitched to the head piece. Then a cape six and a half inches deep, cut circular, is stitched to the back of the head piece, extending from one point to the other of the visor. Over this seam inside is stitched a tape easing for a double draw string to pucker it to suit different sized heads. The visor is made double, and open inside, so that the leather visor of a common fatigue cap can be inserted, as the Havelock is thrown over it, which can be done while on the march almost instantly. The inner edge of the under part of the visor is hemmed, and the front edge stitched, and the outer edge of the cape hemmed.”

Other protective devices seem to have gained more currency than the ill-fated havelock. These included oil cover and the so-called “glazed” cap. Both were made from enameled cloth. The oil cover fit over the top of the cap and was secured in place by the chinstrap buttons. Two examples of this accessory include those of Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron, 5th Company, Louisiana Washington Artillery, and 2nd Lieutenant J.B.W. Phillips, Company B, 18th Battalion South Carolina Artillery. Even Captain E.C. Wharton, Houston Quartermaster, wrote requirements for “oil silk cap covers” in 1863.[109]

A step up from the oil cover was the glazed cap, essentially a cap made entirely of enameled cloth. There are numerous pictures of soldiers wearing this type of cap, so it must have enjoyed some popularity, albeit limited. Contemporary images document its use in Richmond, Virginia and Charleston, South Carolina.[110] Both the Alabama State Quartermaster and the Savannah Post Quartermaster mention “Glazed Caps” and “oil cloth caps” in their inventories from 1861 to 1863.[111] The Confederate quartermaster in Jackson, Mississippi also reported purchasing 195 oil cloth caps on 2 April 1863.[112]

Confederate Usage of Caps

Confederate uniformologists have pondered how widespread the use of caps was by Southern troops. The following thoughts on the subject offer some insights.

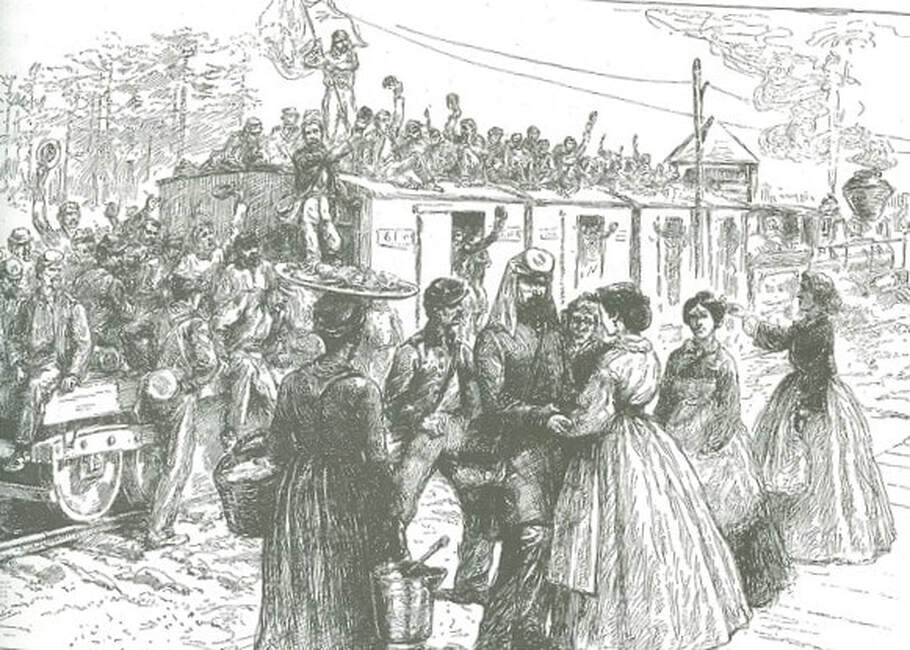

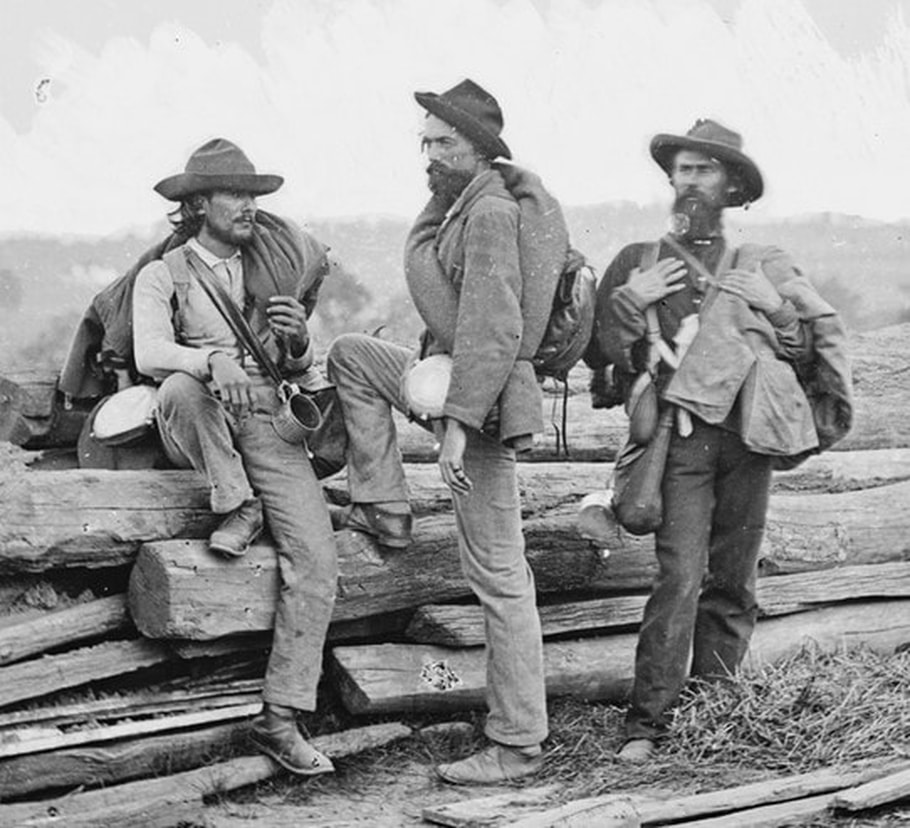

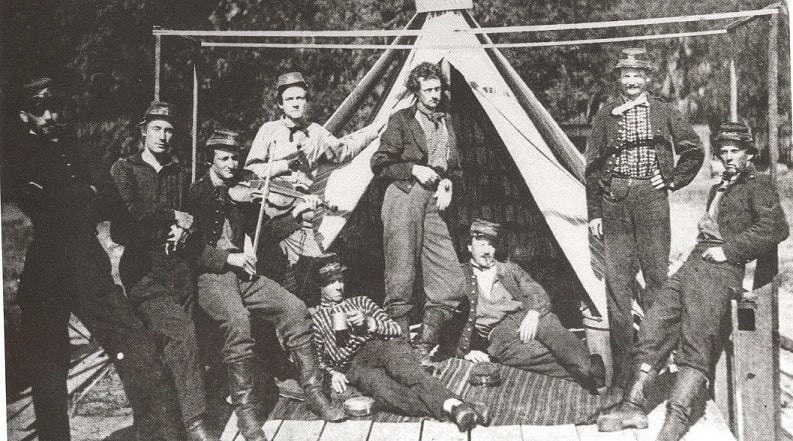

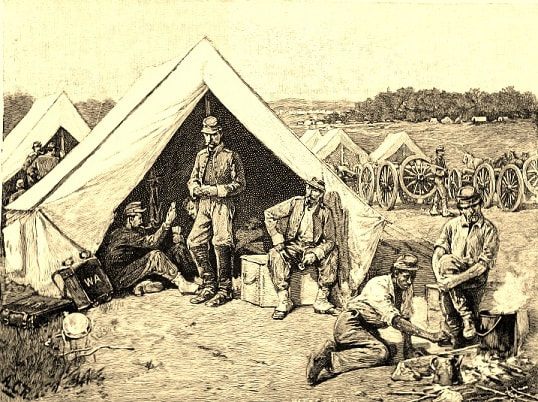

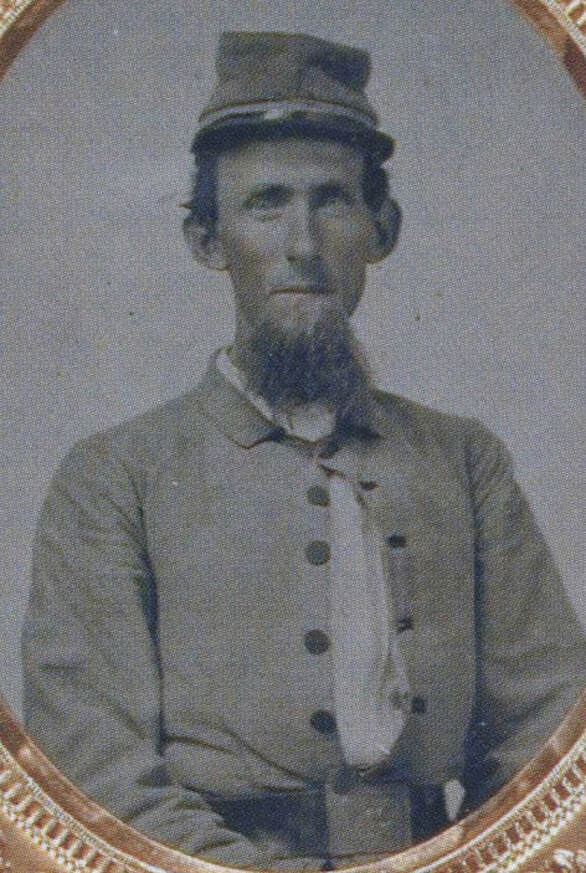

The cap was the official headdress of the Confederate army, but was not the most widely worn type of headgear by Southern soldiers. The comfortable wool hat held that honor. After all, the hat provided better protection against the sun, rain and cold. Despite that, many regiments went to war wearing the cap out of a fierce sense of military pride. Contemporary images document this well. First Sergeant William Watson of the 3rd Louisiana Infantry remarked on this when his regiment departed for Missouri in the summer of 1861. He wrote, “The dress uniforms with tinsel and feathered hats were thrown aside, and fatigue or fighting uniforms and foraging caps substituted.”[113] This attachment to the cap did not last long, however. Confederate veteran, Carlton McCarthy wrote after the war, “Caps were destined to hold out longer than some other uncomfortable things, but they finally yielded to the demands of comfort and common sense, and a good soft felt hat was worn instead.”[114] The preference for the wool hat, both from the ranks and in the high command, remained constant throughout the war. A look at Confederate prisoners taken in June 1864 from the Army of Northern Virginia bears this out. Counting those soldiers with hats versus caps yielded the following results: of 39 soldiers counted at Belle Plain, only four had caps (11%). Of 86 soldiers counted at White House Landing, only 13 had caps (15%). When Confederate Quartermaster-General A.R. Lawton wrote about procurement, on September 21, 1864, to Major J.B. Ferguson, Confederate Quartermaster, Liverpool, England, Lawton stated, “You had also better purchase… felt hats… A cheap and serviceable felt hat would be very acceptable for the Army.”[115] Nonetheless, many troops continued to wear caps. By analyzing clothing rolls, written accounts, photographs and sketches, we can get an idea of the frequency.

Confederate uniformologists have pondered how widespread the use of caps was by Southern troops. The following thoughts on the subject offer some insights.

The cap was the official headdress of the Confederate army, but was not the most widely worn type of headgear by Southern soldiers. The comfortable wool hat held that honor. After all, the hat provided better protection against the sun, rain and cold. Despite that, many regiments went to war wearing the cap out of a fierce sense of military pride. Contemporary images document this well. First Sergeant William Watson of the 3rd Louisiana Infantry remarked on this when his regiment departed for Missouri in the summer of 1861. He wrote, “The dress uniforms with tinsel and feathered hats were thrown aside, and fatigue or fighting uniforms and foraging caps substituted.”[113] This attachment to the cap did not last long, however. Confederate veteran, Carlton McCarthy wrote after the war, “Caps were destined to hold out longer than some other uncomfortable things, but they finally yielded to the demands of comfort and common sense, and a good soft felt hat was worn instead.”[114] The preference for the wool hat, both from the ranks and in the high command, remained constant throughout the war. A look at Confederate prisoners taken in June 1864 from the Army of Northern Virginia bears this out. Counting those soldiers with hats versus caps yielded the following results: of 39 soldiers counted at Belle Plain, only four had caps (11%). Of 86 soldiers counted at White House Landing, only 13 had caps (15%). When Confederate Quartermaster-General A.R. Lawton wrote about procurement, on September 21, 1864, to Major J.B. Ferguson, Confederate Quartermaster, Liverpool, England, Lawton stated, “You had also better purchase… felt hats… A cheap and serviceable felt hat would be very acceptable for the Army.”[115] Nonetheless, many troops continued to wear caps. By analyzing clothing rolls, written accounts, photographs and sketches, we can get an idea of the frequency.

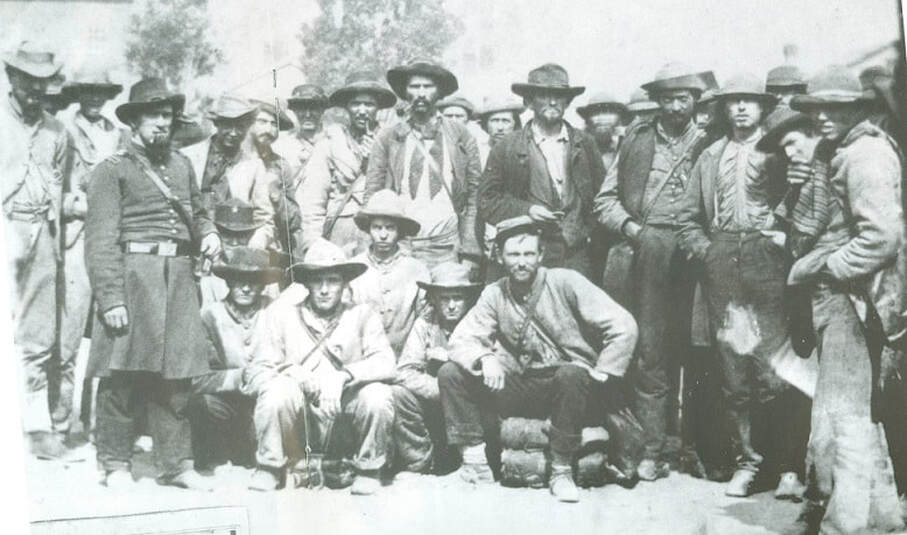

084d: Another image of Confederate prisoners, taken after their arrival in Chicago, shows all of them, save one, wearing hats: 26 out 27! These Confederates were likely from the Western theater, judging from the absence among them of the Army of Northern Virginia's characteristic Richmond Depot jacket. In fact, the soldier squatting on the left side of the Federal officer wears an Atlanta-Columbus Depot jacket. Courtesy of Military Images, September-October 1994, p. 32.

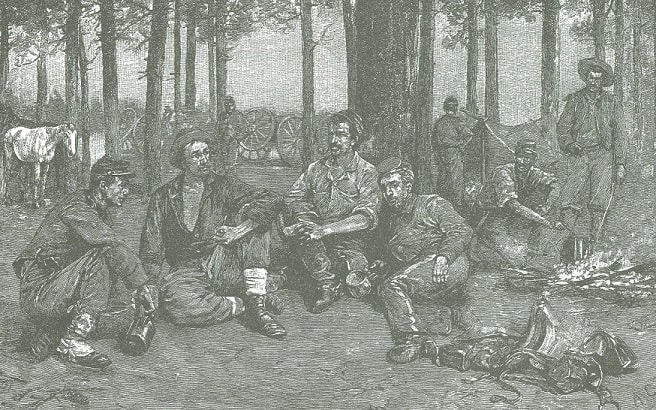

The usage of caps seems to have been tied closely to the soldier’s branch. Artillerymen seem to have worn them more than other troops. Department of the Trans-Mississippi clothing rolls bear out that caps accounted for over half the headgear that artillery commands drew. The distribution of captured Union army headgear at San Antonio through the end of 1862 supports this trend. The Confederates had seized 2,761 Union forage caps and 4,857 Hardee hats at the San Antonio arsenal in February 1861. Artillery commands quickly gobbled up the captured artillery caps, taking but few Hardee hats. The 3rd Texas Infantry drew roughly equal quantities of each headgear during this period, taking at least 328 Federal forage caps during this period, but no less than 251 Hardee hats. Cavalry commands showed a decided preference for hats, taking no less than 670 Hardees and only 342 Union forage caps by the end of 1862. These issues may indicate what each branch preferred, but they may also reflect what was drawn out of necessity. Furthermore, commanders, wishing their troops to maintain a uniform appearance, may have ordered their soldiers to draw caps. This was the case in some regiments, such as the Kentucky Brigade in the Army of Tennessee, where the wearing of caps was mandatory on the parade ground.[116] It may also have been the case in the 36th Texas Cavalry when its soldiers drew Union cavalry forage caps in December 1862, in addition to Hardee hats.[117]

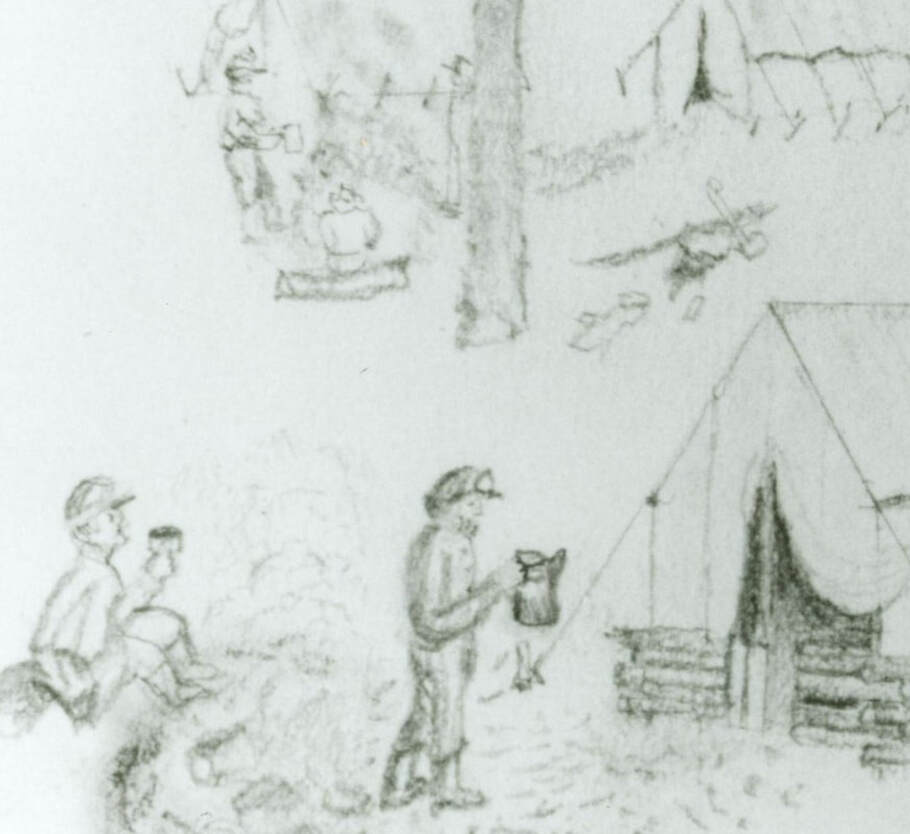

While records show a trend for artillery usage of caps, some infantry and cavalry continued to wear the cap throughout the war. For instance, Morgan Wolfe Merrick, a prolific sketch artist of the 3rd Regiment, Arizona Cavalry Brigade, depicted the soldiers of his regiment wearing caps at Holley, Arkansas in the winter of 1862-63.[118] The 3rd Texas Infantry, the 33rd Texas Cavalry and the 8th Texas Cavalry Battalion drew cadet-gray cloth caps from San Antonio from late 1862 through early 1863.[119] This may reflect a dire necessity for headgear when hats were not available, or a command imperative for military appearance, rather than a preference for caps.

As more hats became available in the department, the infantry drew proportionally more. For instance, clothing receipts from the 8th and 16th Infantry Regiments, covering the period from January to September 1863, show that they drew only hats. Clothing rolls from the 20th and 21st Texas Infantry Regiments, dated March through June 1863, show the 20th drawing caps and the 21st taking about equal amounts of hats and caps.[120]

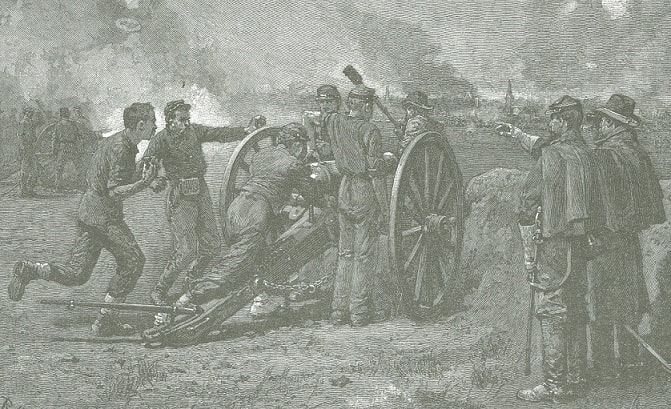

During the same time that the infantry was drawing mostly hats, artillery commands continued to draw more caps. The 8th Texas Field Battery drew cadet gray caps during the winter of 1862-63.[121] In May 1863, the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery and the 2nd Texas Field Battery drew caps, while the 8th Texas Field Battery took hats that month. Merrick’s drawings of the 1st Confederate Battery wearing caps in June 1863 confirm the tendency.

During the same time that the infantry was drawing mostly hats, artillery commands continued to draw more caps. The 8th Texas Field Battery drew cadet gray caps during the winter of 1862-63.[121] In May 1863, the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery and the 2nd Texas Field Battery drew caps, while the 8th Texas Field Battery took hats that month. Merrick’s drawings of the 1st Confederate Battery wearing caps in June 1863 confirm the tendency.

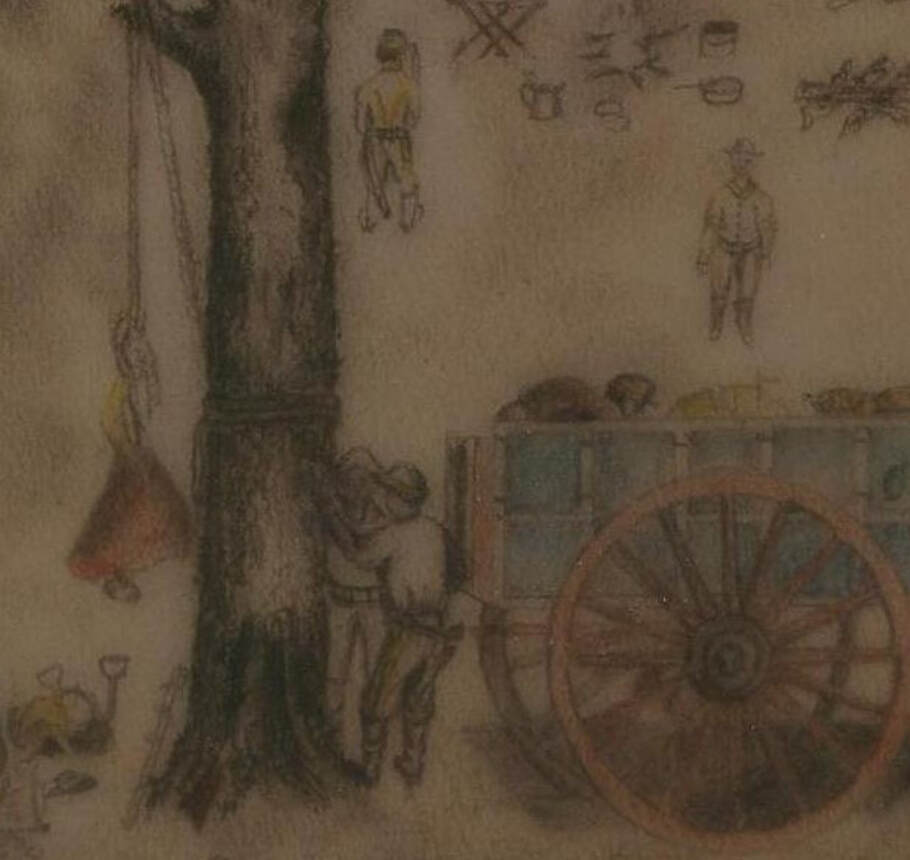

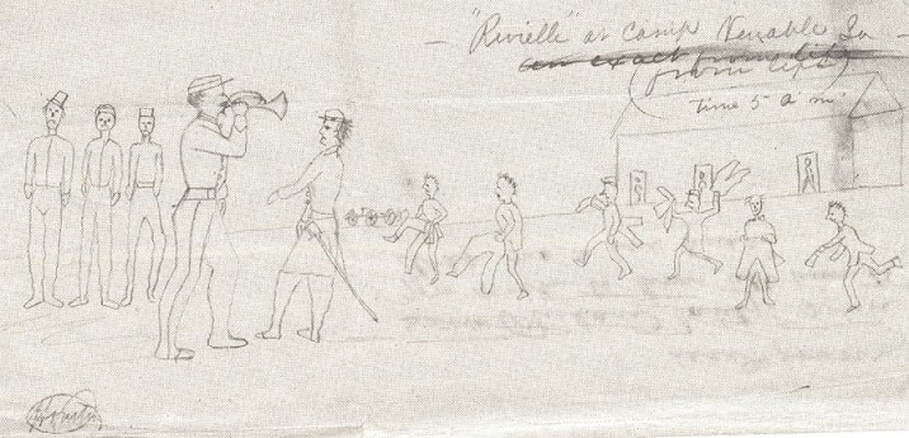

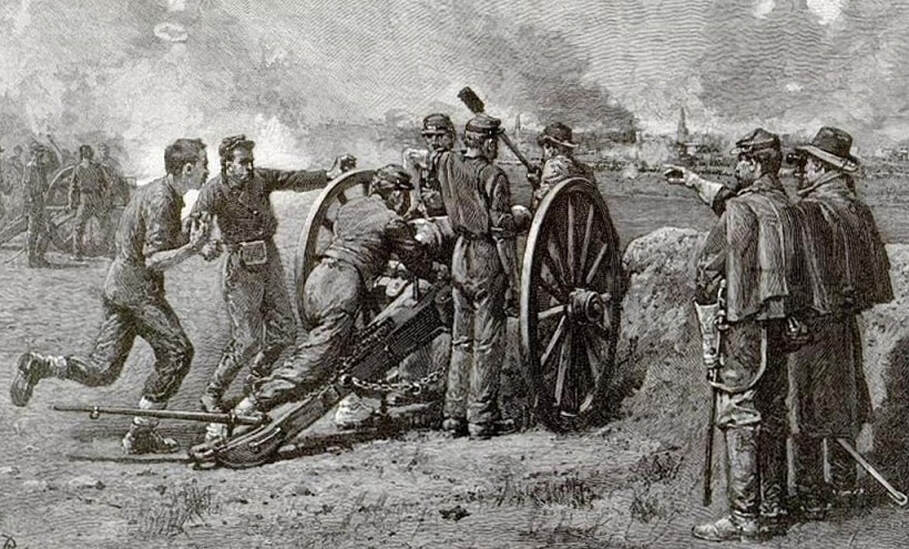

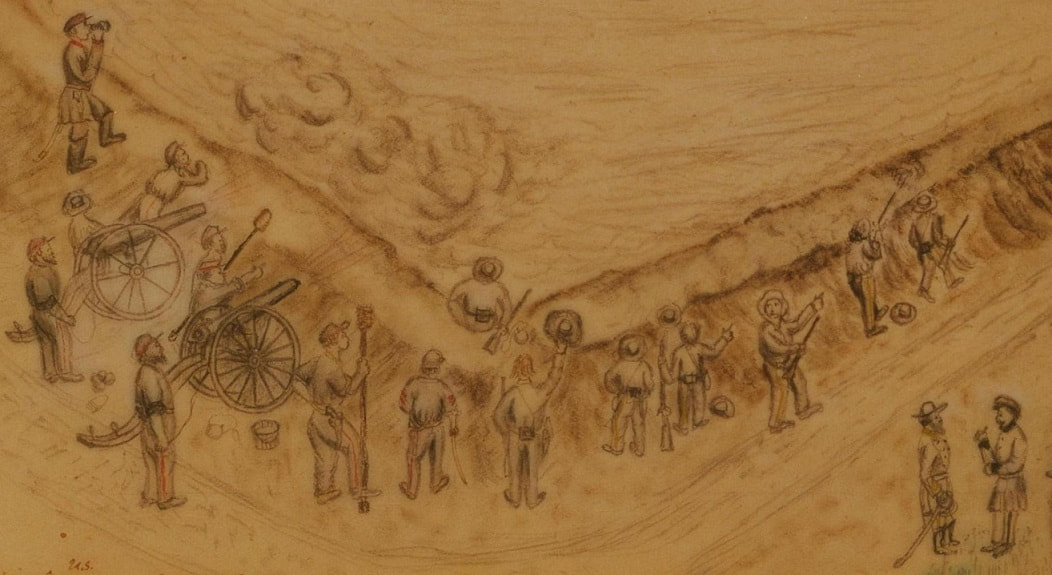

087a: Merrick’s sketches of the 1st Confederate Field Battery, made in West Louisiana during the summer of 1863, showed all of the artillerymen wearing caps. The supporting infantry were all depicted wearing hats. Image courtesy of From Desert to Bayou, The Civil War Journal and Sketches of Morgan Wolfe Merrick, and the Daughters of the Texas Revolution.

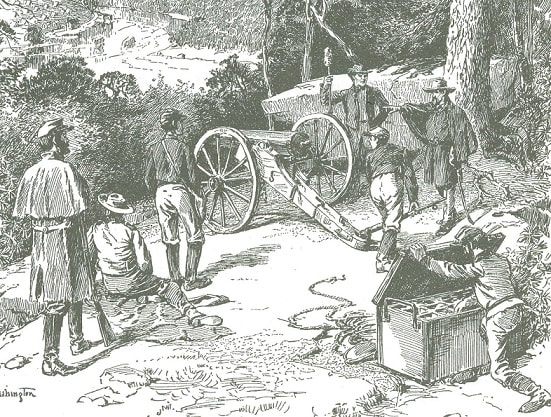

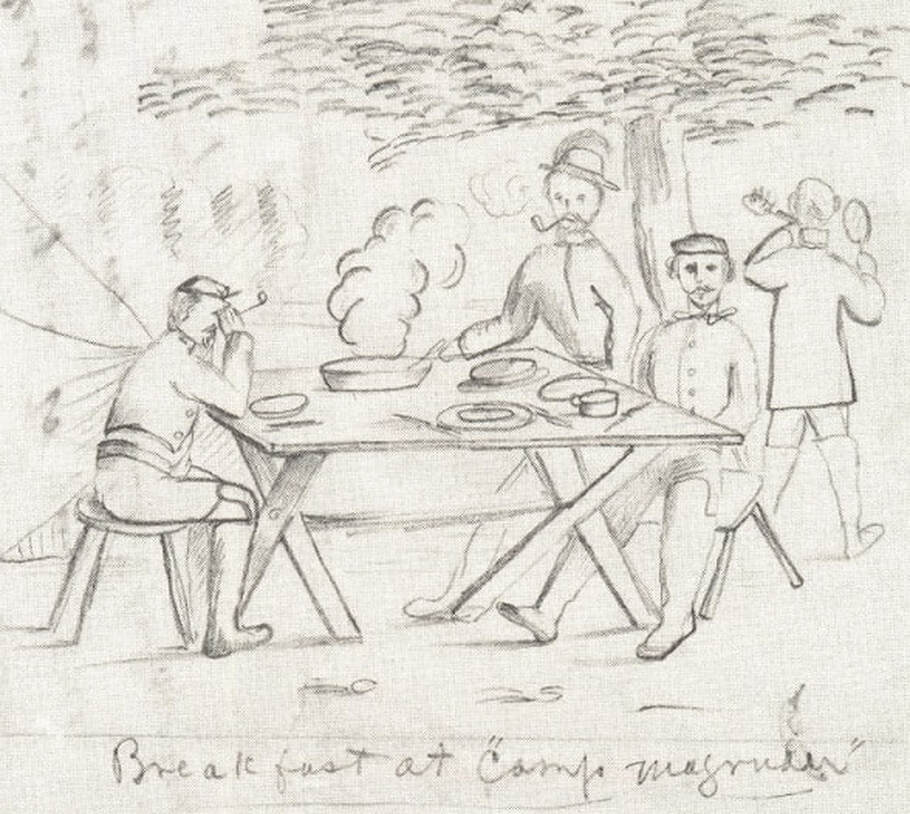

The few clothing rolls for cavalry troops in Texas, dated after January 1863, indicate that the cavalry drew hats. A photo of the Company D, 4th Regiment, Arizona Cavalry Brigade, dated from late 1863 to early 1864, shows the entire group wearing black hats. Likewise, a similar group image of Texans in Washington County, ca 1863, shows all wearing hats. Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Fremantle described the 33rd Texas Cavalry in South Texas as all wearing “high black felt hats” in the spring of 1863.[122] Surprisingly, Morgan Wolfe Merrick’s sketches of the 3rd Arizona Cavalry depict many cavalrymen wearing chasseur style caps in the field. Merrick’s sketches of scenes in Louisiana during the summer of 1863 show about a quarter to a third of the men wearing caps.[123] Moreover, Merrick’s sketches of the 1st Confederate Battery from the same region and time show virtually all of its artillerymen wearing chasseur caps. The same observation was made for McMahan’s Texas Battery in 1864-65. Two pencil sketches by Lieutenant Sam Houston, Jr. show all the members of the battery wearing chasseur caps.[124] Merrick’s and Houston’s artwork provides evidence that some cavalrymen wore caps, and that the cap was quite popular with the artillery.

088c: In stark contrast to images of Trans-Mississippi cavalry and infantry, McMahan’s Texas Field Battery were sketched wearing caps. This image shows the battery at Camp Magruder in July 1864. Image courtesy of Frazier’s Love and War, pp. 317; and, the Huntsville, Texas archival collection, sketches by Lieutenant Sam Houston, Jr., CSA.

The preference for caps was not always tied to branch-of-service. Availability of headgear assuredly played a role, as well. The distribution of Old Army stocks of caps from San Antonio in 1861 and 1862 reflected, to a degree, what was available. Likewise, troops in the rest of the Department of the Trans-Mississippi used their own wool hats until the quartermaster had military headgear to issue, whether caps or hats. By the fall of 1862, four large Trans-Mississippi clothing depots were in full operation: Little Rock, Monroe, Houston and San Antonio. All of these depots made caps to go with their soldier suits. By the spring of 1863, more Confederate hats, whether locally contract-made, imported and depot-made, were becoming available for issue, and subsequently, the proportion of hat issues increased. Indeed, Houston Depot Quartermaster, Captain Edward C. Wharton, mentioned repeatedly in 1863 that the depot needed to fabricate, “…a plain but serviceable wool hat ‑ of which the Troops stand much in need,” and wrote three estimates for clothing citing the requirement for, “Wool Hats in place of Caps” and “Hats of Black Wool instead of Caps.”[125] He would have preferred to issue hats rather than caps, but in the absence of a supply of hats, he continued to make caps. During October and November 1863, Wharton fabricated 874 caps, representing all three branches.[126] In early 1864, the Houston Clothing Bureau established a hat factory that presumably alleviated the hat shortage. In a cumulative report of issues for the period of March 1864 through January 1865, the Houston Depot reported only one partial issue of caps, that being to Nichols’ Light Artillery (15th Texas Field Battery), which received 184 hats and caps for its 75 men. All other commands had received only hats during that time. By January 1865, the Houston Depot had ceased making caps altogether.[127]

In some exceptional cases, infantry and cavalry commands may even have preferred wearing caps over hats. Two such examples from the Western theater are indicative of this. The 6th Mississippi Infantry Regiment, over the course of the war, from October 1861 through April 1864, drew 937 caps and 488 hats, taking caps at a two-to-one ratio over hats. Most of these caps were issued from various depots in Mississippi and Alabama.[128] A cavalry command in Alabama also wore caps late in the war, as noted by E.N. Gilpin, 3rd Iowa Cavalry. Gilpin recorded in his journal on 10 April 1865, in Church Hill, Alabama, the following about the Confederate cavalry, “They were gallant fellows, as they rode at a gallop, their long hair blowing behind their little Secesh caps. As they leaped the fences, it was a goodly sight.”[129] There is also evidence of cavalry commands in the Army of Northern Virginia using caps. In Part 2 of this study, two of the surviving general service, Richmond caps were worn by cavalrymen late in the war: First Sergeant William Edward Kite, 3rd Battalion Virginia Mounted Reserves, and Charles Alexander Womack, 6th Virginia Cavalry. Interestingly, First Lieutenant William H. Harwood, 3rd Virginia Cavalry, whose cap was likewise featured in Part 2, drew a total of 52 caps (and no hats) for his company on four occasions between 26 May 1863 and 24 March 1864.[130] While these examples offer only a random sampling of cap-wearing infantry and cavalry commands, they emphasize the pitfalls of overly broad generalizations, as well as the complex nature of Confederate uniformology.

While the preponderance of evidence proves that most Confederate infantry and cavalry soldiers preferred and wore hats rather than caps, it also shows that the Confederate artillery had a penchant for wearing caps. The reason for this preference might be understood when considering the artillery’s background, education, discipline and esprit d’ corps. My studies of Confederate armies have led me to this conclusion. While the artillery in both the eastern and western theaters exhibited high discipline and superior conduct, I offer examples from the Trans-Mississippi to illustrate this point.

Numerous inspection reports from throughout the Trans-Mississippi Department rate the artillery as the most disciplined and best instructed of the commands in their respective districts. The infantry followed behind the artillery in efficiency, and the cavalry, notorious for its ill-discipline, lack of military instruction and overall unruliness, trailed behind the rest. Colonel Ben Allston, Inspector General for the Trans-Mississippi, noted in his report for the last quarter of 1863 that artillery batteries generally maintained their equipment better and demonstrated a higher degree of discipline, drill and instruction.[131] Infantry regiments were often cited for lack of instruction and overall lack of military bearing. The cavalry, however, was singled out for the most scathing judgments. Almost all cavalry commands were found deficient in some respect. General Edmund Kirby Smith, Department Commander, considered these shortcomings so egregious that he wanted to disband at least two Texas cavalry regiments, reduce their officers to the ranks and transfer both the defrocked officers and the men to infantry regiments as replacements. While the two discredited regiments avoided being disbanded, Kirby Smith’s sentiments reflect the overall, low opinion that the high command had for the cavalry. The poor reputation of the Trans-Mississippi’s cavalry was shared throughout the Confederacy. While the lack of discipline among Confederate infantry was often an embarrassment, the Southern cavalry’s penchant for trouble was a by-word throughout the land. Many Confederate citizens had more dread of their own cavalry than of the Yankees. Confederate officers frequently commented that many cavalry regiments were more liabilities than assets. Yet, none of this censure is found regarding the artillery.

The artillery attracted a higher caliber of soldier than the other branches. As a rule, artillerymen were better educated, came from more urban backgrounds and were better able to adapt to military life than their infantry and cavalry counterparts. Indeed, artillerymen had to exercise more discipline, maintain better care of equipment and function well as a member of a gun crew. They also had to practice mechanical or mathematical skills to operate around the gun. With this basis, it is conceivable that higher caliber soldiers gravitated towards the artillery. Likewise, given their superior discipline and instruction, the artillerymen might easily develop a greater esprit d ‘corps than the infantry and cavalry. This pride could manifest itself in such outward signs as scarlet facings and the distinctly military cap: proud symbols that showed affiliation with the artillery.

The less disciplined, but no less patriotic, infantry and cavalry had less of a sense of esprit d ’corps than the artillery and were more given to practicality and comfort. It was only natural that they eschew the cap in favor of the wool hat.

In some exceptional cases, infantry and cavalry commands may even have preferred wearing caps over hats. Two such examples from the Western theater are indicative of this. The 6th Mississippi Infantry Regiment, over the course of the war, from October 1861 through April 1864, drew 937 caps and 488 hats, taking caps at a two-to-one ratio over hats. Most of these caps were issued from various depots in Mississippi and Alabama.[128] A cavalry command in Alabama also wore caps late in the war, as noted by E.N. Gilpin, 3rd Iowa Cavalry. Gilpin recorded in his journal on 10 April 1865, in Church Hill, Alabama, the following about the Confederate cavalry, “They were gallant fellows, as they rode at a gallop, their long hair blowing behind their little Secesh caps. As they leaped the fences, it was a goodly sight.”[129] There is also evidence of cavalry commands in the Army of Northern Virginia using caps. In Part 2 of this study, two of the surviving general service, Richmond caps were worn by cavalrymen late in the war: First Sergeant William Edward Kite, 3rd Battalion Virginia Mounted Reserves, and Charles Alexander Womack, 6th Virginia Cavalry. Interestingly, First Lieutenant William H. Harwood, 3rd Virginia Cavalry, whose cap was likewise featured in Part 2, drew a total of 52 caps (and no hats) for his company on four occasions between 26 May 1863 and 24 March 1864.[130] While these examples offer only a random sampling of cap-wearing infantry and cavalry commands, they emphasize the pitfalls of overly broad generalizations, as well as the complex nature of Confederate uniformology.

While the preponderance of evidence proves that most Confederate infantry and cavalry soldiers preferred and wore hats rather than caps, it also shows that the Confederate artillery had a penchant for wearing caps. The reason for this preference might be understood when considering the artillery’s background, education, discipline and esprit d’ corps. My studies of Confederate armies have led me to this conclusion. While the artillery in both the eastern and western theaters exhibited high discipline and superior conduct, I offer examples from the Trans-Mississippi to illustrate this point.

Numerous inspection reports from throughout the Trans-Mississippi Department rate the artillery as the most disciplined and best instructed of the commands in their respective districts. The infantry followed behind the artillery in efficiency, and the cavalry, notorious for its ill-discipline, lack of military instruction and overall unruliness, trailed behind the rest. Colonel Ben Allston, Inspector General for the Trans-Mississippi, noted in his report for the last quarter of 1863 that artillery batteries generally maintained their equipment better and demonstrated a higher degree of discipline, drill and instruction.[131] Infantry regiments were often cited for lack of instruction and overall lack of military bearing. The cavalry, however, was singled out for the most scathing judgments. Almost all cavalry commands were found deficient in some respect. General Edmund Kirby Smith, Department Commander, considered these shortcomings so egregious that he wanted to disband at least two Texas cavalry regiments, reduce their officers to the ranks and transfer both the defrocked officers and the men to infantry regiments as replacements. While the two discredited regiments avoided being disbanded, Kirby Smith’s sentiments reflect the overall, low opinion that the high command had for the cavalry. The poor reputation of the Trans-Mississippi’s cavalry was shared throughout the Confederacy. While the lack of discipline among Confederate infantry was often an embarrassment, the Southern cavalry’s penchant for trouble was a by-word throughout the land. Many Confederate citizens had more dread of their own cavalry than of the Yankees. Confederate officers frequently commented that many cavalry regiments were more liabilities than assets. Yet, none of this censure is found regarding the artillery.

The artillery attracted a higher caliber of soldier than the other branches. As a rule, artillerymen were better educated, came from more urban backgrounds and were better able to adapt to military life than their infantry and cavalry counterparts. Indeed, artillerymen had to exercise more discipline, maintain better care of equipment and function well as a member of a gun crew. They also had to practice mechanical or mathematical skills to operate around the gun. With this basis, it is conceivable that higher caliber soldiers gravitated towards the artillery. Likewise, given their superior discipline and instruction, the artillerymen might easily develop a greater esprit d ‘corps than the infantry and cavalry. This pride could manifest itself in such outward signs as scarlet facings and the distinctly military cap: proud symbols that showed affiliation with the artillery.

The less disciplined, but no less patriotic, infantry and cavalry had less of a sense of esprit d ’corps than the artillery and were more given to practicality and comfort. It was only natural that they eschew the cap in favor of the wool hat.

089a: This image of William W. Sewell, 5th Company, Washington Artillery, offers a look at a cap issued in 1863-64, prior to Sewell’s death at Dallas, Georgia, 28 May 1864. The ubiquitous crossed cannon with brass letters on either side are in evidence. The letters are partially obscured, but may be “WA” for Washington Artillery. The cap appears to be an 1861 pattern gray cap with a red band. Sewell’s mirror image has not been horizontally flipped. Image courtesy of Glen C. Cangelosi, M.D., WashingtonArtillery.com website.

089c Andrew R. Blakely, 2nd Company, Washington Artillery, wears the early cap with the red sides and crown over a red band. The crossed cannon badge and “WA” letters were the standard for this company’s caps. The image dates to 1861. Image courtesy of Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana.

090a: An original, early-war, Washington Artillery cap shows the opulence that the company members enjoyed: fine red caps with blue bands; a quality leather visor; gold lace; and ornate brass fittings. The cap was a pre-cursor for the Confederate regulation cap of 1862. Artifact courtesy of Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana.

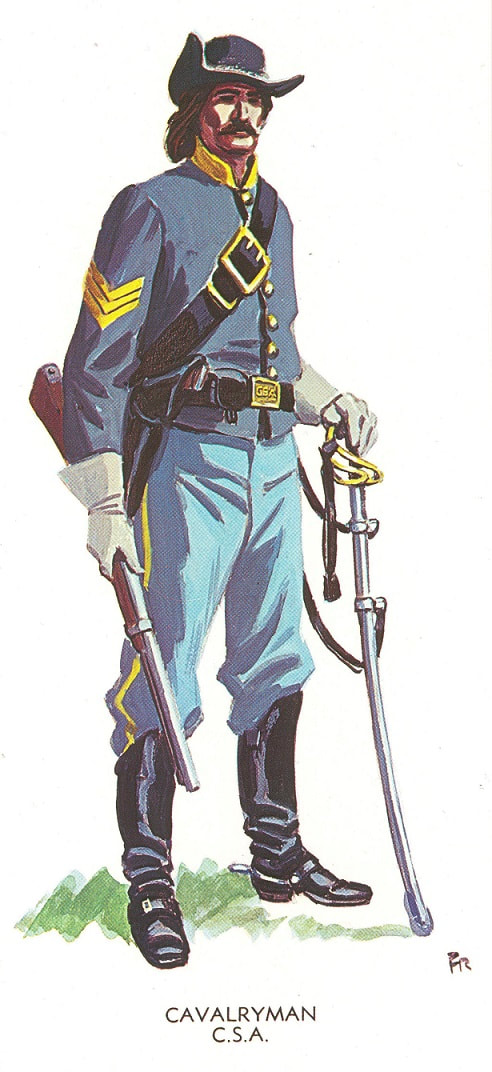

091a-c: Frederic Ray made some highly representative, soldier art paintings for the Civil War Centennial, that included a cavalryman, artilleryman and infantryman. Ray used the correct cadet-gray color for the soldiers’ jackets; light blue for the trousers; spot-on headgear; and, trim red for the artillery uniform. The cavalry uniform, with its yellow trim, may be somewhat wishful, but the Houston Depot did make this uniform. Ray did an outstanding job of accurately representing the Confederate soldier fully thirty years before all of the information about these uniforms came into wide circulation.

A Gallery of Noteworthy Caps:

Having discussed the many types of Confederate caps, their places of origin and their usage, it is worth having a look at some noteworthy examples. This gallery of various caps offers perspectives of typical features, as well as unique characteristics. The pictures round out the study of enlisted caps with a plethora of representative caps.

A Gallery of Noteworthy Caps:

Having discussed the many types of Confederate caps, their places of origin and their usage, it is worth having a look at some noteworthy examples. This gallery of various caps offers perspectives of typical features, as well as unique characteristics. The pictures round out the study of enlisted caps with a plethora of representative caps.

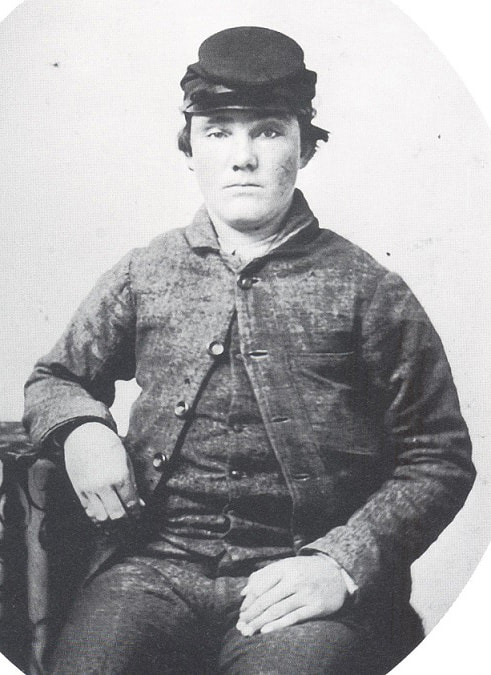

092a: This well-known image of three Company D, 3rd Georgia Infantry comrades in Virginia during the winter of 1861-62 depicts James D. Jackson wearing a very early-war chasseur cap. Jackson’s cap has a distinctly light-colored band, presumably blue. The characteristic thin leather visor and shiny leather, varnished components are in evidence. The mirror image has been flipped horizontally to provide a true perspective. Image courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

093: Cadet John McNish Hazlehurst, of the Georgia Military Institute, wore this solid red cap during the war. This well-made cap features a functioning chinstrap, Georgia state seal buttons, and fine, red wool basic cloth. It reflects the quality of caps unaffected by the exigencies of war. McNish wore the cap as a cadet, and he probably wore it to war when the GMI cadets were mobilized as the Georgia Battalion of Cadets in the spring of 1864. The battalion remained in active service until May 1865. Image courtesy of Echoes of Glory: Arms and Equipment of the Confederacy, p. 149, and artifact courtesy of the Atlanta History Center, Atlanta, Georgia.

Before closing out this gallery, it is worth having a look at some of the other caps that Confederates used, albeit not chasseur or forage caps. Included are examples of the US Army pattern 1839 forage cap, used chiefly during the Mexican War, as well as some Confederate States Navy caps.

094j: Unfortunately, no Confederate Navy enlisted caps have survived with provenance. In any case, the Confederate cap was a copy of the Union navy cap, except it was to be made of cadet gray cloth. The image depicts this type of flat-bodied cap, albeit a Union example. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Liljenquist collection, 36800-36870v.

Legacy and Lore

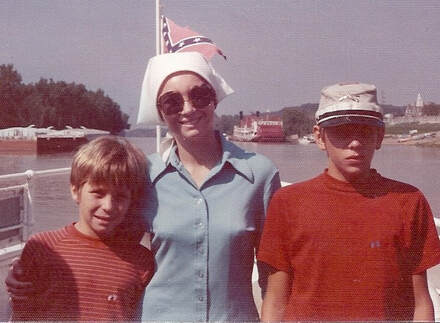

The final section of this study concerns the legacy and lore surrounding the Confederate cap. As early as the turn of the twentieth century, the Confederate cap had become a Southern icon, alongside the turned-up slouch hat, the bedroll and the Confederate battle flag. This icon has informed the casting of Confederate statues, has become embedded in the film industry as a standard prop and has found a place in the art and folk customs of the South. The Confederate cap has also been re-dubbed the “kepi” since the end of the war, undoubtedly to give it its own distinctive name. The following images provide a sampling of the Confederate kepi’s place in the Southern perception of the its Confederate heritage. The kepi is prominent in graphic art, fine art, statues, the film industry, and heritage attire in costumes and novelty wear. It also worn as an accessory as part of living history, reenactment and commemorative events. This usage has spanned the time from the late nineteenth century to the twenty first century. The kepi still lives today!

The final section of this study concerns the legacy and lore surrounding the Confederate cap. As early as the turn of the twentieth century, the Confederate cap had become a Southern icon, alongside the turned-up slouch hat, the bedroll and the Confederate battle flag. This icon has informed the casting of Confederate statues, has become embedded in the film industry as a standard prop and has found a place in the art and folk customs of the South. The Confederate cap has also been re-dubbed the “kepi” since the end of the war, undoubtedly to give it its own distinctive name. The following images provide a sampling of the Confederate kepi’s place in the Southern perception of the its Confederate heritage. The kepi is prominent in graphic art, fine art, statues, the film industry, and heritage attire in costumes and novelty wear. It also worn as an accessory as part of living history, reenactment and commemorative events. This usage has spanned the time from the late nineteenth century to the twenty first century. The kepi still lives today!

Conclusion

The quintessential Confederate cap has become an iconic symbol of the Southerners’ war for independence. Indeed, its usage outlived the war, and continues to serve as a visible symbol of Southern identity at today’s historical, commemorative ceremonies, and in the graphic art that harkens back to the Confederacy. Given the “kepi’s” important symbolism to Southerners, it is worth looking back at its origins, form, usage and history to understand the genesis of this unique cap, and to understand why Southerners hold it dear to their hearts to this very day.

Copyright: This study and its contents are copyrighted to the Adolphus Confederate Uniforms website with the exception of those images that are part of the Library of Congress collection, or in the public domain.

Bibliography:

[97] Clothing Rolls, Carded and Not Carded, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, National Archives, Washington DC, 3rd Texas Infantry, 4th quarter 1862 and 1st quarter 1863, (hereafter, CR with applicable citation); CR Company D, 8th Texas Cavalry Battalion, 4 January 1863; CSR Texas, M323, Roll 161, Santo Benevides’ Company, 33rd Texas Cavalry.

[98] CR 1st Texas Heavy Artillery; CR 8th Texas Field Battery.

[99] Moore, Michael Rugeley, The Texas Penitentiary and Textile Production in the Civil War Era, Honor’s Paper, Thesis, HIS 679H, University of Texas, Austin, April 1984, pp. 139-140, (hereafter, Moore); also Norman D. Brown (Editor). One of Cleburne’s Command, The Civil War Reminiscences and Diary of Capt. Samuel T. Foster, Granbury’s Texas Brigade, CSA, University of Texas Press, Austin and London, 1980, p. 8.

[100] Columbus Daily Sun, Georgia, September 16, 1862, the Columbus, Georgia quartermaster depot sent in September 1862 to the “Army of Arkansas” a small shipment of clothing: 7,000 garments.

[101] Shibley, pp. 33, 81.

[102] C.L. Webster III compiled numerous references about this topic. He included these in his book, Webster III, C.L., Entrepot: Government Imports into the Confederate States, Edinborough Press, Roseville, Minnesota, 2010. I have included the Entrepot page numbers, as well as the source citation for each reference as follows: note 193, page 201, CSR Officer, W.L. Sharkey, M331, Roll 223, Letter October 9, 1862; note 194 & 195, page 201, OR Series 1, Volume 15, pp. 867, 872; note 192, 196 & 197, pages 201-202, CSRs Officer, W.L. Sharkey, M331, Roll 223, Letter October 9, 1862, and OR Series 1, Volume 15, pp. 867, 872; note 198, page 202, CSRs Officer, W.L. Sharkey, M331, Roll 223, Letter October 12, 1862, and OR Series 1, Volume 13, Chapter 25, page 916, letter, Major-General, Commanding, Th. H. Holmes, Little Rock Arkansas, November 14, 1862, to General T.C. Hindman, Commanding Army of the Northwest; and, Circular, November 10, 1862, Head Quarters First Corps, Trans Miss Army Camp Mulberry, Major General Hindman, and OR Series 1, Volume 15, Chapter 27, page 867, letter, E. Surget, Assistant Adjutant-General, HQ, District of Western Louisiana, Alexandria, La., November 17, 1862 (received at Richmond, Va., December 11), to Brig. Gen. M.L. Smith, Comdg. Confederate States Forces at Vicksburg, Miss., and page 872, R. Taylor, Major-General, Commanding, HQ District of Western Louisiana, Alexandria, La., November 21, 1862 (received December 4, 1862), to General S. Cooper, C.S.A., Adjutant and Inspector General, Richmond, Va. See also, Moore, p. 138.

[103] Shibley manuscript, “Dear Parents,” The Civil War Letters of the Shibley Brothers of Van Buren Arkansas, William H.H. & John Samuel, Company G, 22nd Arkansas Infantry, p. 81, 5 August 1863, (hereafter, Shibley); CSR Texas, 17th Texas Infantry, M323, Roll 386, 20 December 1862, and Roll 390, 30 June and 24 Sep 1863.

[104] Wharton, 89-J.41, p. 50, describes cap components as follows, “Pasteboard (for caps) [crown and band stiffening]; Leather vizors, made in the Shoe Shop”; p. 51, “Caps ‑ Grey Cloth body (with red, blue or yellow narrow bands to indicate the Service) 12 yds, dble width, 144 caps ‑ Bleached Domestic or Calico used for lining & Pasteboard, for stiffening; Yellow, Red, or Blue Material (whatever can be had) to make the bands; ‑ plain Leather Vizors, from the Shoe Shop.”

[105] Wharton, 16 October 1863: report of the Condition of the Clothing Bureau to 11 October 1863, Document C, includes the entry: “Caps are manufactured by me from scraps of Cloth, cut up in making Jackets & Trowsers. The vizors are made in the Govt. Shoe Shop.”

[106] Louisiana State University Libraries, Edward Clifton Wharton Family Papers, Houston Clothing Bureau, Expenditure Report, November 1863, (hereafter, Wharton, Expenditures, November 1863).

[107] CSR Officer M331, Roll 178, Letter from Captain W.J. Mills, Assistant Quartermaster, CSA, Houston, Texas to Captain E.P. Turner, AAG, District of Texas, October 5, 1863, clothing on hand Houston Clothing Depot, as of 1 October 1863, (hereafter, Mills, 5 October 1863).

[108] Daily Advocate, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, May 29, 1861, p. 2, c. 5.

[109] Wharton, 141-J.41. Wharton forwarded his requirements for clothing materials to General J.B. Magruder in July 1863, and included the request in his report of 22 December 1863. The required materials for caps included: Artillery, 1,000 yards red cloth double width; Cavalry, 3,000 yards yellow cloth double width; Infantry, 6,000 yards light blue cloth double width; Infantry [and others], 5,000 yards dark blue cloth double width; Oil silk for cap cover, 12,000 yards double width; White cambric or white linen for cap linings, 25.000 yards single width; Glazed stout leather for cap visors for 100,000 caps; Glazed leather for chin straps for 100,000 caps; Metal buttons, small for caps for 220,000 caps.

[110] Image courtesy of the Library of Congress: Coles Island No. 4, LC-DIG-stereo-2s03890. Light artillery gun crew with the caption, “Coles Island No 4.”, “Marion Artillery of Charleston.” The entire gun crew wears caps, and four of the caps appear to be shiny, enameled cloth, of the chasseur pattern. One of these is worn with the chinstrap down.

[111] Alabama Department of Archives and History, SG 006471, Reels 8 and 20: quarterly returns 1861, Duff Green, QM General; quarterly returns 1st quarter 1862 to 1st quarter 1864, W.R. Pickett, AAQM; State of Alabama standard prices for quartermaster articles, 3rd quarter 1862 and 3rd and 4th quarters 1863; State of Alabama Seamstress Account, Montgomery, December 1864, 600 glazed caps were issued from late 1861 through December 1862, and some still in stock in 1863. Williams, Bob, Confederate Quartermaster Stores: Savannah Coastal Defenses, website “Plowshares & Bayonets:” A Scholarly Blog of the 26th North Carolina Regiment, 26nc.org/blog/, posted January 26, 2014, October 31, 1863, Savannah post quartermaster inventory included 175 oil cloth caps.

[112] CSA Citizens M346, Roll 1086, S. Weill, April 2, 1863, purchase by Captain William Gillaspie, Jackson, Mississippi.

[113] Watson, William, Life in the Confederate Army, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge and London, 1995, p. 124, May 1861, New Orleans, Louisiana, Company K, 3rd Louisiana Infantry.

[114] McCarthy, Carlton; Detailed Minutiae of Soldier Life in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 1993, re-print, (original published by McCarthy in Richmond, 1882), p. 21, (hereafter, McCarthy). McCarty served as an artilleryman with the 2nd Company Richmond Howitzers, Cutshaw’s Artillery Battalion, Captain J.F. Jones’ Company, Virginia Artillery, Army of Northern Virginia, from November 1864 through the end of the war.

[115] OR, Series 4, Volume 3, Section 2, p. 674, A.R. Lawton, Quartermaster-General, Richmond, 21 September 1864 to Major J.B. Ferguson, Confederate Quartermaster, Liverpool.

[116] Davis, p. 167, reference to the Kentucky Brigade having to wear their caps on parade, ca. 14 February 1863.

[117] Texas State Library and Archives, Box 401-839, Folder 1, Inventories Compiled by Reuben M. Potter, Military Store Keeper, U.S.A., San Antonio, Texas, March 19, 1861. Potter’s inventories include Old Army stocks of headgear available to the Confederate quartermaster, which was duly issued in the Western Sub-District of Texas.

[118] Thompson, Jerry D., From Desert to Bayou, The Civil War Journal and Sketches of Morgan Wolfe Merrick, Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso, 1991, p. 95, (hereafter, Merrick).

[119] CR 3rd Texas Infantry, 4th quarter 1862 and 1st quarter 1863; CR 8th Texas Cavalry Battalion, 4 January 1863, Co. D; M323, Roll 161, Santo Benavides’ Company, 33rd Texas Cavalry.

[120] CR 8th, 16th, 20th and 21st Texas Infantry Regiments.

[121] CR 1st Texas Heavy Artillery and 8th Texas Field Battery.

[122] Lord, Walter (editor), The Fremantle Diary: Being the Journal of Lieutenant Colonel James Lyon Arthur Fremantle, Coldstream Guards, on his Three Months in the Southern States, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1954, pp. 7 and 9, (hereafter, Fremantle).

[123] Merrick, pp. 47, 51, 52 and 81.

[124] Frazier, Donald S. and Hillhouse, Andrew, editors, Love and War: The Civil War Letters and Medicinal Book of Augustus V. Ball, transcribed by Anne Ball Ryals, State House Press, Buffalo Gap, Texas, 2010, pp. 317 and 362, (hereafter, Ball). The sketches included in the book were by Lieutenant Sam Houston, Jr., and are part of the Huntsville Texas archival collection, (hereafter, Lieutenant Houston). Ball served with the 23rd Texas Cavalry and McMahan’s Battery.

[125] Wharton, 89-J.41, pp. 71-72; 112-J.41; 113-J.41; 141-J.41.

[126] Mills, 5 October 1863; Wharton, Expenditures, November 1863.

[127] Officers M331, Roll 242, Captain E.W. Taylor’s report of March 1865 for clothing furnished at Houston from February1864 through February 1865. Captain E.W. Taylor was the post quartermaster at Houston in 1864-65. He noted in his report that Nichols’ Battery Light Artillery drew 184 “Hats & Caps” on 12 December 1864, with 75 men on the rolls. See also Houston QM Clothing Ledger, 1865.

[128] Howell, H. Grady, Going to Meet the Yankees: A History of the “Bloody Sixth” Mississippi Infantry, C.S.A., Chickasaw Bayou Press, 1981, see the cumulative issues for the regiment in the appendices.

[129] The Last Campaign: A Cavalryman’s Journal by E.N. Gilpin, Third Iowa Cavalry, Reprint from The Journal of the U.S. Cavalry Association, p. 646.

[130] CSRs Virginia, M324, Roll 30, First Lieutenant William H. Harwood, Co D, 3rd Virginia Cavalry.

[131] National Archives, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, Confederate Inspection Records, M935, Roll 8, 3-J-41; Inspection Report of Troops in the Trans Miss Dept, 19 January 1864.

The quintessential Confederate cap has become an iconic symbol of the Southerners’ war for independence. Indeed, its usage outlived the war, and continues to serve as a visible symbol of Southern identity at today’s historical, commemorative ceremonies, and in the graphic art that harkens back to the Confederacy. Given the “kepi’s” important symbolism to Southerners, it is worth looking back at its origins, form, usage and history to understand the genesis of this unique cap, and to understand why Southerners hold it dear to their hearts to this very day.

Copyright: This study and its contents are copyrighted to the Adolphus Confederate Uniforms website with the exception of those images that are part of the Library of Congress collection, or in the public domain.

Bibliography:

[97] Clothing Rolls, Carded and Not Carded, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, National Archives, Washington DC, 3rd Texas Infantry, 4th quarter 1862 and 1st quarter 1863, (hereafter, CR with applicable citation); CR Company D, 8th Texas Cavalry Battalion, 4 January 1863; CSR Texas, M323, Roll 161, Santo Benevides’ Company, 33rd Texas Cavalry.

[98] CR 1st Texas Heavy Artillery; CR 8th Texas Field Battery.

[99] Moore, Michael Rugeley, The Texas Penitentiary and Textile Production in the Civil War Era, Honor’s Paper, Thesis, HIS 679H, University of Texas, Austin, April 1984, pp. 139-140, (hereafter, Moore); also Norman D. Brown (Editor). One of Cleburne’s Command, The Civil War Reminiscences and Diary of Capt. Samuel T. Foster, Granbury’s Texas Brigade, CSA, University of Texas Press, Austin and London, 1980, p. 8.

[100] Columbus Daily Sun, Georgia, September 16, 1862, the Columbus, Georgia quartermaster depot sent in September 1862 to the “Army of Arkansas” a small shipment of clothing: 7,000 garments.

[101] Shibley, pp. 33, 81.

[102] C.L. Webster III compiled numerous references about this topic. He included these in his book, Webster III, C.L., Entrepot: Government Imports into the Confederate States, Edinborough Press, Roseville, Minnesota, 2010. I have included the Entrepot page numbers, as well as the source citation for each reference as follows: note 193, page 201, CSR Officer, W.L. Sharkey, M331, Roll 223, Letter October 9, 1862; note 194 & 195, page 201, OR Series 1, Volume 15, pp. 867, 872; note 192, 196 & 197, pages 201-202, CSRs Officer, W.L. Sharkey, M331, Roll 223, Letter October 9, 1862, and OR Series 1, Volume 15, pp. 867, 872; note 198, page 202, CSRs Officer, W.L. Sharkey, M331, Roll 223, Letter October 12, 1862, and OR Series 1, Volume 13, Chapter 25, page 916, letter, Major-General, Commanding, Th. H. Holmes, Little Rock Arkansas, November 14, 1862, to General T.C. Hindman, Commanding Army of the Northwest; and, Circular, November 10, 1862, Head Quarters First Corps, Trans Miss Army Camp Mulberry, Major General Hindman, and OR Series 1, Volume 15, Chapter 27, page 867, letter, E. Surget, Assistant Adjutant-General, HQ, District of Western Louisiana, Alexandria, La., November 17, 1862 (received at Richmond, Va., December 11), to Brig. Gen. M.L. Smith, Comdg. Confederate States Forces at Vicksburg, Miss., and page 872, R. Taylor, Major-General, Commanding, HQ District of Western Louisiana, Alexandria, La., November 21, 1862 (received December 4, 1862), to General S. Cooper, C.S.A., Adjutant and Inspector General, Richmond, Va. See also, Moore, p. 138.

[103] Shibley manuscript, “Dear Parents,” The Civil War Letters of the Shibley Brothers of Van Buren Arkansas, William H.H. & John Samuel, Company G, 22nd Arkansas Infantry, p. 81, 5 August 1863, (hereafter, Shibley); CSR Texas, 17th Texas Infantry, M323, Roll 386, 20 December 1862, and Roll 390, 30 June and 24 Sep 1863.

[104] Wharton, 89-J.41, p. 50, describes cap components as follows, “Pasteboard (for caps) [crown and band stiffening]; Leather vizors, made in the Shoe Shop”; p. 51, “Caps ‑ Grey Cloth body (with red, blue or yellow narrow bands to indicate the Service) 12 yds, dble width, 144 caps ‑ Bleached Domestic or Calico used for lining & Pasteboard, for stiffening; Yellow, Red, or Blue Material (whatever can be had) to make the bands; ‑ plain Leather Vizors, from the Shoe Shop.”

[105] Wharton, 16 October 1863: report of the Condition of the Clothing Bureau to 11 October 1863, Document C, includes the entry: “Caps are manufactured by me from scraps of Cloth, cut up in making Jackets & Trowsers. The vizors are made in the Govt. Shoe Shop.”

[106] Louisiana State University Libraries, Edward Clifton Wharton Family Papers, Houston Clothing Bureau, Expenditure Report, November 1863, (hereafter, Wharton, Expenditures, November 1863).

[107] CSR Officer M331, Roll 178, Letter from Captain W.J. Mills, Assistant Quartermaster, CSA, Houston, Texas to Captain E.P. Turner, AAG, District of Texas, October 5, 1863, clothing on hand Houston Clothing Depot, as of 1 October 1863, (hereafter, Mills, 5 October 1863).

[108] Daily Advocate, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, May 29, 1861, p. 2, c. 5.

[109] Wharton, 141-J.41. Wharton forwarded his requirements for clothing materials to General J.B. Magruder in July 1863, and included the request in his report of 22 December 1863. The required materials for caps included: Artillery, 1,000 yards red cloth double width; Cavalry, 3,000 yards yellow cloth double width; Infantry, 6,000 yards light blue cloth double width; Infantry [and others], 5,000 yards dark blue cloth double width; Oil silk for cap cover, 12,000 yards double width; White cambric or white linen for cap linings, 25.000 yards single width; Glazed stout leather for cap visors for 100,000 caps; Glazed leather for chin straps for 100,000 caps; Metal buttons, small for caps for 220,000 caps.

[110] Image courtesy of the Library of Congress: Coles Island No. 4, LC-DIG-stereo-2s03890. Light artillery gun crew with the caption, “Coles Island No 4.”, “Marion Artillery of Charleston.” The entire gun crew wears caps, and four of the caps appear to be shiny, enameled cloth, of the chasseur pattern. One of these is worn with the chinstrap down.

[111] Alabama Department of Archives and History, SG 006471, Reels 8 and 20: quarterly returns 1861, Duff Green, QM General; quarterly returns 1st quarter 1862 to 1st quarter 1864, W.R. Pickett, AAQM; State of Alabama standard prices for quartermaster articles, 3rd quarter 1862 and 3rd and 4th quarters 1863; State of Alabama Seamstress Account, Montgomery, December 1864, 600 glazed caps were issued from late 1861 through December 1862, and some still in stock in 1863. Williams, Bob, Confederate Quartermaster Stores: Savannah Coastal Defenses, website “Plowshares & Bayonets:” A Scholarly Blog of the 26th North Carolina Regiment, 26nc.org/blog/, posted January 26, 2014, October 31, 1863, Savannah post quartermaster inventory included 175 oil cloth caps.

[112] CSA Citizens M346, Roll 1086, S. Weill, April 2, 1863, purchase by Captain William Gillaspie, Jackson, Mississippi.

[113] Watson, William, Life in the Confederate Army, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge and London, 1995, p. 124, May 1861, New Orleans, Louisiana, Company K, 3rd Louisiana Infantry.

[114] McCarthy, Carlton; Detailed Minutiae of Soldier Life in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 1993, re-print, (original published by McCarthy in Richmond, 1882), p. 21, (hereafter, McCarthy). McCarty served as an artilleryman with the 2nd Company Richmond Howitzers, Cutshaw’s Artillery Battalion, Captain J.F. Jones’ Company, Virginia Artillery, Army of Northern Virginia, from November 1864 through the end of the war.

[115] OR, Series 4, Volume 3, Section 2, p. 674, A.R. Lawton, Quartermaster-General, Richmond, 21 September 1864 to Major J.B. Ferguson, Confederate Quartermaster, Liverpool.

[116] Davis, p. 167, reference to the Kentucky Brigade having to wear their caps on parade, ca. 14 February 1863.

[117] Texas State Library and Archives, Box 401-839, Folder 1, Inventories Compiled by Reuben M. Potter, Military Store Keeper, U.S.A., San Antonio, Texas, March 19, 1861. Potter’s inventories include Old Army stocks of headgear available to the Confederate quartermaster, which was duly issued in the Western Sub-District of Texas.

[118] Thompson, Jerry D., From Desert to Bayou, The Civil War Journal and Sketches of Morgan Wolfe Merrick, Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso, 1991, p. 95, (hereafter, Merrick).

[119] CR 3rd Texas Infantry, 4th quarter 1862 and 1st quarter 1863; CR 8th Texas Cavalry Battalion, 4 January 1863, Co. D; M323, Roll 161, Santo Benavides’ Company, 33rd Texas Cavalry.

[120] CR 8th, 16th, 20th and 21st Texas Infantry Regiments.

[121] CR 1st Texas Heavy Artillery and 8th Texas Field Battery.

[122] Lord, Walter (editor), The Fremantle Diary: Being the Journal of Lieutenant Colonel James Lyon Arthur Fremantle, Coldstream Guards, on his Three Months in the Southern States, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1954, pp. 7 and 9, (hereafter, Fremantle).

[123] Merrick, pp. 47, 51, 52 and 81.

[124] Frazier, Donald S. and Hillhouse, Andrew, editors, Love and War: The Civil War Letters and Medicinal Book of Augustus V. Ball, transcribed by Anne Ball Ryals, State House Press, Buffalo Gap, Texas, 2010, pp. 317 and 362, (hereafter, Ball). The sketches included in the book were by Lieutenant Sam Houston, Jr., and are part of the Huntsville Texas archival collection, (hereafter, Lieutenant Houston). Ball served with the 23rd Texas Cavalry and McMahan’s Battery.

[125] Wharton, 89-J.41, pp. 71-72; 112-J.41; 113-J.41; 141-J.41.

[126] Mills, 5 October 1863; Wharton, Expenditures, November 1863.

[127] Officers M331, Roll 242, Captain E.W. Taylor’s report of March 1865 for clothing furnished at Houston from February1864 through February 1865. Captain E.W. Taylor was the post quartermaster at Houston in 1864-65. He noted in his report that Nichols’ Battery Light Artillery drew 184 “Hats & Caps” on 12 December 1864, with 75 men on the rolls. See also Houston QM Clothing Ledger, 1865.

[128] Howell, H. Grady, Going to Meet the Yankees: A History of the “Bloody Sixth” Mississippi Infantry, C.S.A., Chickasaw Bayou Press, 1981, see the cumulative issues for the regiment in the appendices.

[129] The Last Campaign: A Cavalryman’s Journal by E.N. Gilpin, Third Iowa Cavalry, Reprint from The Journal of the U.S. Cavalry Association, p. 646.

[130] CSRs Virginia, M324, Roll 30, First Lieutenant William H. Harwood, Co D, 3rd Virginia Cavalry.

[131] National Archives, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, Confederate Inspection Records, M935, Roll 8, 3-J-41; Inspection Report of Troops in the Trans Miss Dept, 19 January 1864.