|

|

A Mississippi Depot Uniform

By Fred Adolphus, 2 February 2011

By Fred Adolphus, 2 February 2011

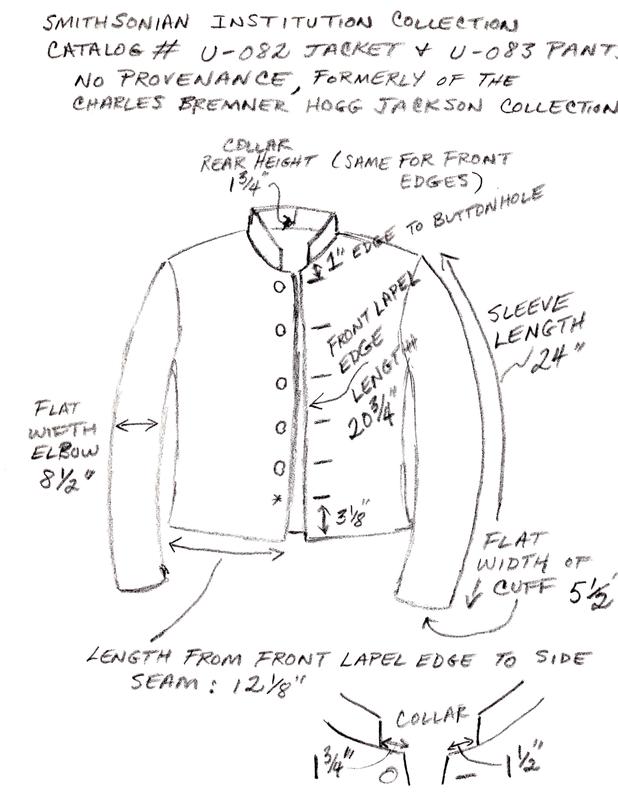

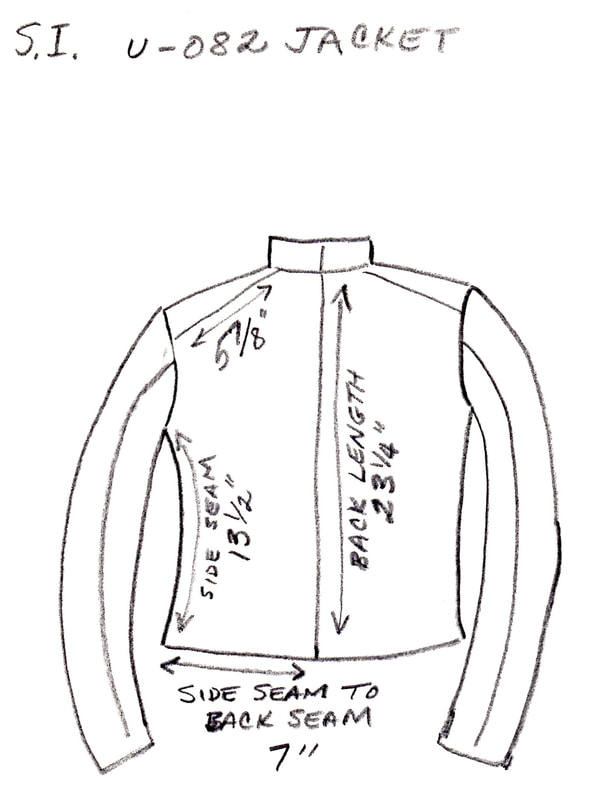

The Smithsonian Institution houses an interesting Confederate uniform that has not seen the light of day for many years.[1] It consists of a jacket and pair of trousers without provenance, and identified only by its donor, Charles Bremner Hogg Jackson; accession number 1980.0399; and, catalog number U-082 for the jacket, and catalog number U-083 for the pants.

I first viewed this uniform in May 1996. At the time, the uniform had so much residual lanolin that it posed a contamination hazard to other textiles, and had to be stored apart. Since then, conservators at the Smithsonian Institution have stabilized the uniform, and the staff allowed me to examine it again in December 2010.

The jacket shares many of the characteristics noted in uniforms from Deep South factories. The jacket is made of plain woven, woolen-cotton cloth. The cotton warp is undyed, but exposure to the woolen yarn’s lanolin has given the cotton fibers a yellowish-tan cast. The woolen weft yarn is also apparently undyed, but has a light grayish tinge. These weave colors give the cloth a very light brown, or tan, color at almost any distance. The jacket has six buttonholes closing the front with five Roman “I” buttons remaining intact. The buttons are solid cast brass, the faces of some marred by imperfect sand-casting. The lining is unbleached white osnaburg. It has one inside, patch-style pocket on the left side that may have been added after the jacket was manufactured. The jacket shell and lining are both four-piece construction (two front and two back pieces), and the lining has facing lapels on the front, as well. The sleeves and the collar (both outer and inner pieces) are one-piece construction. There is no topstitching around the edge of the jacket, the collar, or the cuffs. The buttonholes are sewn with light brown cotton thread.

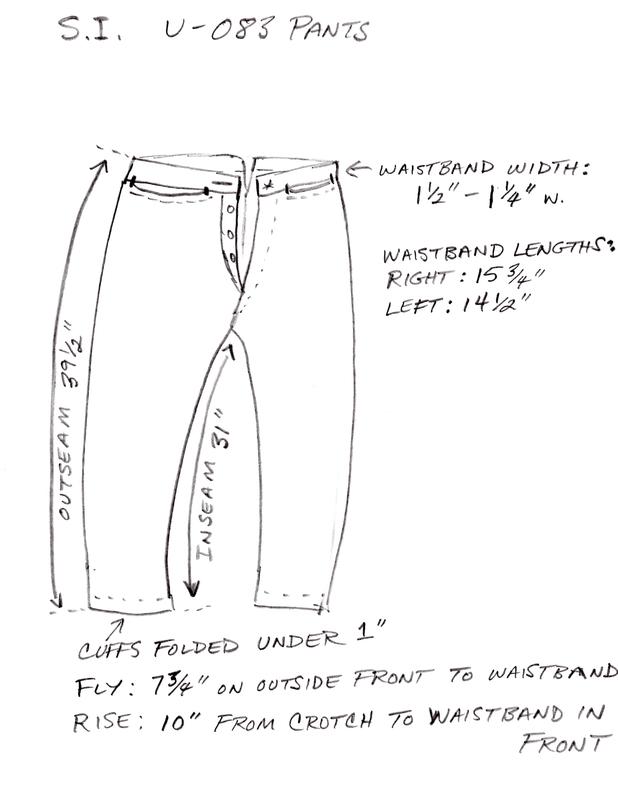

The trousers are truly remarkable. The most salient feature of these woolen-cotton jeans (twill) trousers is the mismatched yarn color in the fabric’s fill weave, or weft. These variances in the shade of the woolen yarn give the effect of stripes throughout the length of the fabric. The most prominent weft yarn color is a grayish-tan. This color, in conjunction with a whitish-yellow cotton warp threads, give the fabric a light tan cast overall. Contrasting with the grayish-tan fill yarns are layers of brownish-gray colored yarns that make up the “stripes.” Neither the weavers nor the uniform manufacturers apparently considered slight variances in weft yarn shade important, for they wove the mismatched yarns into runs of fabric and subsequently cut it into garment components. There is no evidence that the woolen yarn was ever dyed, neither the lighter, nor the darker weft yarns. The browner stripes appear to owe their color to the addition of natural brown-colored fleece fibers (from brown colored sheep) to the spinning process. It might also be noted that the residual lanolin imparted a yellowish-tan tinge to the cotton warp fibers, thereby giving the cloth a tan color.

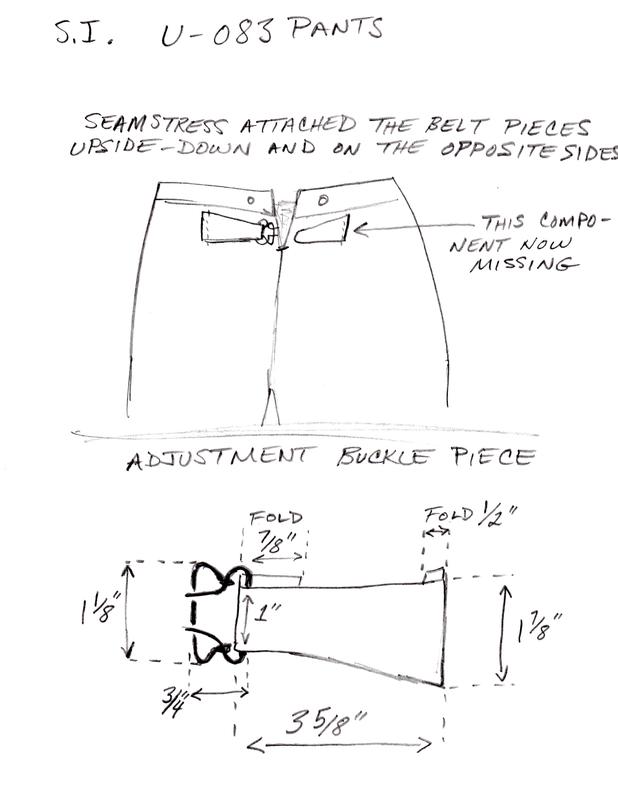

The trousers themselves are typical of most Southern-made, uniform pants. They have a separate waistband, and the lining pieces and pockets are fashioned from unbleached cotton osnaburg. The manufacturer used dark brown cotton thread to topstitch the fly, pocket openings, and buttonholes. The rear waist seam had a two-piece adjustment belt, but the tongue component is missing. The billet component, with its brass buckle, and an osnaburg back facing, is intact, but surprisingly, was attached upside-down on the wrong side (sewn on the left, back panel). Such an over sight is indicative of the quick, careless assembly involved with the mass production of these simple suits. The pockets are “watch pocket” style, opening horizontally at the bottom edge of the waistband, on either side of the fly. The fly has three buttonholes with an additional buttonhole at the waistband. The fly buttons are 5/8 inch, dark horn, and are intact. The button at the waistband is missing, but its retaining button on the reverse (light bone) side is intact. The six, intact, suspender buttons on the waistband are 5/8 inch, lighter horn, or bone. They are attached with white cotton thread. The differences between the fly and suspender buttons, and their thread colors, indicate that the suspender buttons may have been added later.

The U-083 are made almost identically to a pair of pants in the Confederate Memorial Hall collection worn by Nathan Tisdale of the 30th Louisiana Infantry. Tisdale’s pants have a solid provenance to the late-war Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. The similarity between the U-083 pants and Tisdale’s pants suggest that they were made by the same manufacturer.

As mentioned, the U-082/083 uniform retained a significant amount of lanolin in its weft yarns when the Smithsonian Institution acquired it. It was still distinctly greasy when I first examined it in 1996, but has since been cleaned by a professional conservator. It is possible that the mill that processed the raw wool used in this uniform purposely left a quantity of the lanolin intact. This would have facilitated the spinning process. Moreover, it was only necessary to remove most of the lanolin when the intent was to bleach or dye the yarn, something unnecessary if the yarn was to be left undyed. Leaving the lanolin intact left the finished cloth somewhat greasy and smelly, making the clothing uncomfortable for the wearer. One soldier, Ephraim Anderson of the General Sterling Price’s Missouri Brigade, noted that his command received such uniforms in Arkansas on March 1and 2, 1862. Anderson commented: “Our regiment was uniformed here; the cloth was of rough coarse texture, and the cutting and style would have produced a sensation in fashionable circles: the stuff was white, never having been colored, with a goodly supply of grease – the wool had not been purified by any application of water since it had been taken from the back of the sheep. In pulling off and putting on the clothes, the olfactories were constantly exercised with a strong odor of that animal. Our brigade was the only body of troops that had these uniforms issued to them, and were often greeted with a chorus of ba-a-as…Our clothes, however, were strong and serviceable, if we did look and feel somewhat sheepish in them.” Anderson spoke of uniforms issued in Arkansas, but there is a wealth of evidence documenting Confederate white woolen or undyed uniforms in Mississippi.

The U-082/083 uniform reflects many of the practical, no-frills, production methods adopted by Southern clothing factories to quickly mass produce simple cloth and garments. Such expediencies included: the use of undyed, lanolin-rich yarn; the reduction in the number of pieces used in making the jacket (a four-piece body and one-piece sleeves vice a six-piece body and two piece sleeves): the absence of topstitching on the jacket; the use of a single jacket pocket; the lack of suspender buttons on the pants; and finally, the use of mismatched yarn colors in the pants fabric. All of these short cuts are indicative of the "quantity over quality" manufacturing approach.

The production methods may offer clues to the origins of the U-082/083 uniform and indicate where its owner served. Surviving uniforms with sound provenance, whose origins are traced to the small factories in Mississippi, or other factories in the Lower South, share the same essential characteristics of the U-082/083 uniform. A brown, all cotton jeans jacket worn by a soldier named Parker has a similar four-piece body.[2] The sheep’s gray jeans jacket of Edward R. Oldham, 7th Tennessee, is similarly undyed and made without topstitching.[3] The John T. Appler uniform consists of an undyed tan-colored jacket and trousers. The Appler uniform has provenance to the First Missouri Brigade, was probably issued in Mississippi in 1862, and is very similar to the U-082/083 uniform. The Appler jacket has no topstitching, one-piece sleeves, and a four-piece body.[4] Finally, the John Dimitry jacket, Louisiana Crescent Regiment, worn at the Battle of Shiloh, is simply made, without topstitching.[5] Though these uniforms share similarities, they are not identical.

In light of these observations, it is worth nothing that Lower South uniforms are not standardized. Each uniform has its own distinctive tailoring and construction features. This stands in sharp contrast to uniforms made at larger depot operations, such as Richmond; Columbus, Georgia; Montgomery, Columbus, Mississippi; and, in North Carolina. The large depots managed to standardize their patterns, and this is evident in surviving jackets whose tailoring matches that of the other jackets made at the same depot.

The manufacturing system employed in Mississippi, and throughout much of the Lower South, drew on production from numerous small factories. In March of 1863, for instance, there were six clothing factories in Mississippi. The largest, the Jackson Manufactory, produced 5,000 garments weekly. The other five were smaller operations that included the Bankston Factory, Columbus Factory, Enterprise Factory, Natchez Factory, and Woodville Factory. These five together produced 5,000 garments per week (averaging only 500 per factory).[6] The de-centralized nature of the manufacturing process probably fostered a significant degree of diversity in the clothing designs, and quality. This might account for the lack of standardization in uniforms from this region.

Though uniformologists may never know for certain, one can hypothesize that the U-082/083 uniform was drawn, and worn, in the Army of Mississippi during 1862-63, because his jacket and trousers conform to the typical “Mississippi” factory uniform. If that is true, it is significant for two reasons: First, it represents an early war, Western theater uniform, of which there are few survivors. Second, it underscores the efficiency of Southern manufacturing, and how quickly industrial managers grasped the importance of mass production, over lower scale, high quality output.

The U-082/083 uniform tells a story of the Southern people at war, with meager resources, limited capital, and enemy armies raiding their land. Despite the odds against them, they quickly established an industrial complex and managed it effectively to produce the maximum results. This is an example Southerners rising above adversity, and is part of the proud legacy of the Southland today.

I first viewed this uniform in May 1996. At the time, the uniform had so much residual lanolin that it posed a contamination hazard to other textiles, and had to be stored apart. Since then, conservators at the Smithsonian Institution have stabilized the uniform, and the staff allowed me to examine it again in December 2010.

The jacket shares many of the characteristics noted in uniforms from Deep South factories. The jacket is made of plain woven, woolen-cotton cloth. The cotton warp is undyed, but exposure to the woolen yarn’s lanolin has given the cotton fibers a yellowish-tan cast. The woolen weft yarn is also apparently undyed, but has a light grayish tinge. These weave colors give the cloth a very light brown, or tan, color at almost any distance. The jacket has six buttonholes closing the front with five Roman “I” buttons remaining intact. The buttons are solid cast brass, the faces of some marred by imperfect sand-casting. The lining is unbleached white osnaburg. It has one inside, patch-style pocket on the left side that may have been added after the jacket was manufactured. The jacket shell and lining are both four-piece construction (two front and two back pieces), and the lining has facing lapels on the front, as well. The sleeves and the collar (both outer and inner pieces) are one-piece construction. There is no topstitching around the edge of the jacket, the collar, or the cuffs. The buttonholes are sewn with light brown cotton thread.

The trousers are truly remarkable. The most salient feature of these woolen-cotton jeans (twill) trousers is the mismatched yarn color in the fabric’s fill weave, or weft. These variances in the shade of the woolen yarn give the effect of stripes throughout the length of the fabric. The most prominent weft yarn color is a grayish-tan. This color, in conjunction with a whitish-yellow cotton warp threads, give the fabric a light tan cast overall. Contrasting with the grayish-tan fill yarns are layers of brownish-gray colored yarns that make up the “stripes.” Neither the weavers nor the uniform manufacturers apparently considered slight variances in weft yarn shade important, for they wove the mismatched yarns into runs of fabric and subsequently cut it into garment components. There is no evidence that the woolen yarn was ever dyed, neither the lighter, nor the darker weft yarns. The browner stripes appear to owe their color to the addition of natural brown-colored fleece fibers (from brown colored sheep) to the spinning process. It might also be noted that the residual lanolin imparted a yellowish-tan tinge to the cotton warp fibers, thereby giving the cloth a tan color.

The trousers themselves are typical of most Southern-made, uniform pants. They have a separate waistband, and the lining pieces and pockets are fashioned from unbleached cotton osnaburg. The manufacturer used dark brown cotton thread to topstitch the fly, pocket openings, and buttonholes. The rear waist seam had a two-piece adjustment belt, but the tongue component is missing. The billet component, with its brass buckle, and an osnaburg back facing, is intact, but surprisingly, was attached upside-down on the wrong side (sewn on the left, back panel). Such an over sight is indicative of the quick, careless assembly involved with the mass production of these simple suits. The pockets are “watch pocket” style, opening horizontally at the bottom edge of the waistband, on either side of the fly. The fly has three buttonholes with an additional buttonhole at the waistband. The fly buttons are 5/8 inch, dark horn, and are intact. The button at the waistband is missing, but its retaining button on the reverse (light bone) side is intact. The six, intact, suspender buttons on the waistband are 5/8 inch, lighter horn, or bone. They are attached with white cotton thread. The differences between the fly and suspender buttons, and their thread colors, indicate that the suspender buttons may have been added later.

The U-083 are made almost identically to a pair of pants in the Confederate Memorial Hall collection worn by Nathan Tisdale of the 30th Louisiana Infantry. Tisdale’s pants have a solid provenance to the late-war Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. The similarity between the U-083 pants and Tisdale’s pants suggest that they were made by the same manufacturer.

As mentioned, the U-082/083 uniform retained a significant amount of lanolin in its weft yarns when the Smithsonian Institution acquired it. It was still distinctly greasy when I first examined it in 1996, but has since been cleaned by a professional conservator. It is possible that the mill that processed the raw wool used in this uniform purposely left a quantity of the lanolin intact. This would have facilitated the spinning process. Moreover, it was only necessary to remove most of the lanolin when the intent was to bleach or dye the yarn, something unnecessary if the yarn was to be left undyed. Leaving the lanolin intact left the finished cloth somewhat greasy and smelly, making the clothing uncomfortable for the wearer. One soldier, Ephraim Anderson of the General Sterling Price’s Missouri Brigade, noted that his command received such uniforms in Arkansas on March 1and 2, 1862. Anderson commented: “Our regiment was uniformed here; the cloth was of rough coarse texture, and the cutting and style would have produced a sensation in fashionable circles: the stuff was white, never having been colored, with a goodly supply of grease – the wool had not been purified by any application of water since it had been taken from the back of the sheep. In pulling off and putting on the clothes, the olfactories were constantly exercised with a strong odor of that animal. Our brigade was the only body of troops that had these uniforms issued to them, and were often greeted with a chorus of ba-a-as…Our clothes, however, were strong and serviceable, if we did look and feel somewhat sheepish in them.” Anderson spoke of uniforms issued in Arkansas, but there is a wealth of evidence documenting Confederate white woolen or undyed uniforms in Mississippi.

The U-082/083 uniform reflects many of the practical, no-frills, production methods adopted by Southern clothing factories to quickly mass produce simple cloth and garments. Such expediencies included: the use of undyed, lanolin-rich yarn; the reduction in the number of pieces used in making the jacket (a four-piece body and one-piece sleeves vice a six-piece body and two piece sleeves): the absence of topstitching on the jacket; the use of a single jacket pocket; the lack of suspender buttons on the pants; and finally, the use of mismatched yarn colors in the pants fabric. All of these short cuts are indicative of the "quantity over quality" manufacturing approach.

The production methods may offer clues to the origins of the U-082/083 uniform and indicate where its owner served. Surviving uniforms with sound provenance, whose origins are traced to the small factories in Mississippi, or other factories in the Lower South, share the same essential characteristics of the U-082/083 uniform. A brown, all cotton jeans jacket worn by a soldier named Parker has a similar four-piece body.[2] The sheep’s gray jeans jacket of Edward R. Oldham, 7th Tennessee, is similarly undyed and made without topstitching.[3] The John T. Appler uniform consists of an undyed tan-colored jacket and trousers. The Appler uniform has provenance to the First Missouri Brigade, was probably issued in Mississippi in 1862, and is very similar to the U-082/083 uniform. The Appler jacket has no topstitching, one-piece sleeves, and a four-piece body.[4] Finally, the John Dimitry jacket, Louisiana Crescent Regiment, worn at the Battle of Shiloh, is simply made, without topstitching.[5] Though these uniforms share similarities, they are not identical.

In light of these observations, it is worth nothing that Lower South uniforms are not standardized. Each uniform has its own distinctive tailoring and construction features. This stands in sharp contrast to uniforms made at larger depot operations, such as Richmond; Columbus, Georgia; Montgomery, Columbus, Mississippi; and, in North Carolina. The large depots managed to standardize their patterns, and this is evident in surviving jackets whose tailoring matches that of the other jackets made at the same depot.

The manufacturing system employed in Mississippi, and throughout much of the Lower South, drew on production from numerous small factories. In March of 1863, for instance, there were six clothing factories in Mississippi. The largest, the Jackson Manufactory, produced 5,000 garments weekly. The other five were smaller operations that included the Bankston Factory, Columbus Factory, Enterprise Factory, Natchez Factory, and Woodville Factory. These five together produced 5,000 garments per week (averaging only 500 per factory).[6] The de-centralized nature of the manufacturing process probably fostered a significant degree of diversity in the clothing designs, and quality. This might account for the lack of standardization in uniforms from this region.

Though uniformologists may never know for certain, one can hypothesize that the U-082/083 uniform was drawn, and worn, in the Army of Mississippi during 1862-63, because his jacket and trousers conform to the typical “Mississippi” factory uniform. If that is true, it is significant for two reasons: First, it represents an early war, Western theater uniform, of which there are few survivors. Second, it underscores the efficiency of Southern manufacturing, and how quickly industrial managers grasped the importance of mass production, over lower scale, high quality output.

The U-082/083 uniform tells a story of the Southern people at war, with meager resources, limited capital, and enemy armies raiding their land. Despite the odds against them, they quickly established an industrial complex and managed it effectively to produce the maximum results. This is an example Southerners rising above adversity, and is part of the proud legacy of the Southland today.

The solid-cast, Roman 'I' infantry buttons exhibit some flaws. Due to the patina on these buttons, as well as the artificial lighting in the storage collections area, I have wavered between guessing whether they are brass or pewter. After considerable thought, my guess is that these are pewter buttons. Image courtesy of the Armed Forces History Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

A close-up view of the pants fabric reveals that it is a jeans, or twill weave fabric. The jacket is a plain, or tabby weave. Although most Southern factories used the same fabric for both jackets and trousers, this difference could have been by design. Ideally, jackets were to be made with a tighter, more weatherproof plain weave, and trousers were to be made from looser, stretchable twills. Image courtesy of the Armed Forces History Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

The author extends his thanks to the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution staff for their cooperation and assistance with this study, especially Ms. Margaret Vining, Curator, Armed Forces History Collection.

Bibliography

[1] Armed Forces History Division, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Charles Bremner Hogg Jackson collection, Accession Number 1980.0399 (Catalog Number U-082 jacket, and Catalog Number U-083 pants).

[2] Don Troiani collection.

[3] State of Tennessee Museum, Nashville, Tennessee.

[4] Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Missouri.

[5] Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia.

[6] Daily Southern Crisis, Jackson, Mississippi, March 21, 1863, p. 1, c. 1; What Mississippi has Done (from the Mississippian).

Bibliography

[1] Armed Forces History Division, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Charles Bremner Hogg Jackson collection, Accession Number 1980.0399 (Catalog Number U-082 jacket, and Catalog Number U-083 pants).

[2] Don Troiani collection.

[3] State of Tennessee Museum, Nashville, Tennessee.

[4] Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Missouri.

[5] Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia.

[6] Daily Southern Crisis, Jackson, Mississippi, March 21, 1863, p. 1, c. 1; What Mississippi has Done (from the Mississippian).

This website and its content is copyright of Adolphus Confederate Uniforms.

© Adolphus Confederate Uniforms 2010-2021. All rights reserved.

Email us | Copyright | Disclaimer | Terms of Use | PDF Download Help