State of Alabama Quartermaster Uniforms, 1861-1865

by Fred Adolphus

Most Confederate uniform buffs are familiar with the prolific state issue uniforms from North Carolina during the Civil War, but there is far less awareness of the Alabama quartermaster clothing. The State of Alabama manufactured quantities of clothing exclusively for Alabama soldiers, whether in state or Confederate service. From the very beginning of the war, the state operated an effective quartermaster department and established a codified state uniform. Apparently, the greatest activity occurred in 1861, coinciding with the period prior to the establishment of a reliable Confederate quartermaster operation. Less clothing was made and issued from 1862 to late 1864. In the fall of 1864, state issues increased, coinciding with the delivery of imported clothing materials from Peter Tait & Company, Limerick, Ireland.

The first details about the state’s quartermaster operation and products are found in a circular issued by Governor A.B. Moore, August 26, 1861. The circular is reproduced herein from a newspaper column:1

CIRCULAR:

To the Soldiers' Aid Societies Throughout the State,

_______

EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT,

Montgomery, Ala.,

August 26th, 1861.

Alabama has already more than twenty thousand troops in the field, and in a few weeks the number will be largely increased. The winter is rapidly approaching. Many of our soldiers are poor, and without the means of supplying themselves with clothing, except from the commutation money allowed by the Confederate Government, which may not be paid in time to supply themselves. The liberality of the citizens of the more wealthy counties, will, I am assured, in many instances, furnish the Companies from such counties. But that is not enough. There are thousands of our people engaged in this contest whose friends have not the means of supplying them. These men cannot be kept in the field without clothing, and they can only be supplied through the exertions and active benevolence of your societies. The object of this circular is to call your earnest attention to this subject, and to give that method and direction to your labors which will secure the greatest amount of efficiency. The articles which will be required for our soldiers, and to which your attention is especially requested, are chiefly, Uniform Jackets, Great Coats, and Pantaloons, of good strong cloth, of gray color, if possible to be obtained; Shirts, of flannel, or checked or striped cotton; Drawers, of woolen, or cotton-flannel, or stout osnaburgs; Woolen Socks; Gloves Shoes and Blankets.

In order to secure uniformity in the make, I have had sets of patterns cut for the uniform jacket, pantaloons, and great coat, which will be forwarded to the different Aid Societies, in all cases in which it is practicable, together with a model suit of these articles. I also give directions as to the number of each pattern which will be required, and also as to the making, which is important to follow as closely as possible.

It is most earnestly requested that each of the Aid Societies throughout the State should immediately ascertain:

1. The number of each of the articles of clothing named, which they can supply gratuitously, and for what companies, if any, they intend them.

2. The number of uniform jackets, great coats, pantaloons, drawers, shirts and gloves, in addition to those which may be furnished gratuitously, they can make during each of the months of September, and October, if supplied with the material.

This information should be given to me at the earliest possible day, with the address of the Aid Society, and the point, to which the patterns and model suits, can be forwarded by railroad and steamboat communication.

It should be remembered that the soldier can carry but a limited amount of clothing, and therefore the utmost care should be taken that the material is of the most substantial quality, and every article made as strong and durable as possible.

A.B. MOORE.

DIRECTIONS FOR MAKING CLOTHING.

Uniform Jacket: Standing collar of cloth doubled and double stayed, with osnaburg between the cloth, single-breasted, one pocket inside, on the left; one row of seven buttons, large size, on the right side stayed and sewed through; button-hole side perfectly straight from the collar down. One shoulder strap on each shoulder, from seam of sleeve to seam of collar, to button to neck of collar with small button. Two belt straps, one on each side, on bottom of jacket, on side seam, extending upwards, five inches, to button to small button. Sleeves and back to be lined with heavy osnaburgs.

Great Coat: Standing collar, doubled and stayed as uniform jacket, single-breasted, to button with seven large buttons on right side. Movable cape, to come down to elbows, to fasten to bottom of collar with six stout hooks and eyes, and to button in front with five small buttons on right side. Two straps behind, to be just covered by cape, and sewed into the side seams to tighten the coat -- one with one large button and the other with two button holes. Sleeves to be lined with heavy osnaburgs. Cape and back, and forepart of the coat twenty inches down, to be lined with checked or striped osnaburgs. Pockets as in pattern.

Pantaloons, cut full, well stayed in waist-band with double separate stay. Pockets on the side seam rather low down, to be double stayed top and bottom on the seam. Buttons to be sowed clear through. The staying for the bottom of legs, of osnaburg, to extend up eight inches, and to be sewed all round the top. The buttons on the Uniform jacket and Great Coat to be the military brass buttons. Bone buttons for the pantaloons. Button holes are to be worked with twist, coarse silk, or flax thread. The thread used for making to be grey or dark flax from No. 32 to 40.

The following are the numbers of each pattern required to be made out of each one hundred, and in that proportion of a smaller or greater number.

Pattern No. 1……………….25

" " 2……………….30

" " 3……………….25

" " 4……………….15

" " 5………………. 5.

The number of different sizes of shirts, drawers, &c., should be the same as those of the coats and pantaloons, and particular care should be taken, to sew a card with the number of the size of the pattern marked upon it, firmly to each article.

DIRECTIONS FOR PACKING AND FORWARDING.

When a sufficient number of articles are made, to send forward, they will be carefully packed in a box, the number of each article it contains marked legibly on the top, and directed to A. B. Moore, Governor, at Montgomery or Huntsville, as most convenient; to be sent by the usual mode of transportation. The expense of transportation will be paid at these points.

In all cases when the material is furnished gratuitously, and the clothing intended for any particular company, the company will be designated by the name of its Captain, giving his first name or initials, and the number of the Regiment according to the forms below:

FORMS OF DIRECTIONS.

GOV. A. B. MOORE,

Montgomery (or Huntsville.)

For Capt. ------ -----, Company,

Reg. Ala. Vol.

75 Uniform Coats,

75 Great Coats,

75 Pr. Drawers.

______________________________________

GOV. A. B. MOORE,

Montgomery (or Huntsville.)

75 Pants,

50 Shirts.

////////////////////////////////End of Circular///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

The circular provides a plethora of information about Alabama state issue uniforms to include what types of clothing was made, the construction features of clothing, materials used, types of buttons, size markings, sizes fabricated, and percentages of which sizes were to be fabricated. Some of this data can be verified by comparing two surviving Alabama State jackets that were made in 1861 against the prescribed specifications for fabrication. The two surviving jackets, as well as numerous photos, indicate that the specifications were adhered to fairly closely, and that the jackets differed only in the application of their trimmings and small buttons (features that might vary based upon availability of the aforementioned materials).

The first production, which was made by volunteer “Aid Societies”, consisted of jackets, great coats, pantaloons, shirts, drawers, socks, gloves, shoes and blankets. The governor’s office provided patterns for the jackets, great coats and pantaloons, “together with a model suit of these articles,” to ensure uniformity, and they were to be made, “of good strong cloth, of gray color, if possible…” Uniformity for the shirts, drawers and socks was less relevant.

The “Uniform Jacket’s” most salient feature was the “straight from the collar down” edge of the buttonhole side of the front, meaning that the edges of the collar and the lapel were plumb with one another, albeit the lapel described a slight arc from top to bottom. The prescribed features match closely with the two surviving jackets, which, remarkably, survive with photos of the soldiers wearing them.

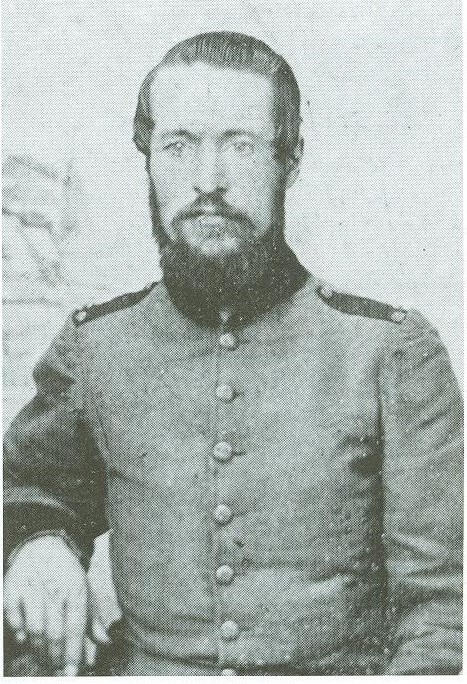

The first of the two surviving jackets was owned by John Young Gilmore, Company E, 3rd Alabama Infantry. Gilmore enlisted in Mobile, April 23, 1861, and served in Virginia. He received multiple wounds at the Battle of Malvern Hill, July 1, 1862, and was mistakenly reported “mortally wounded.” At Malvern Hill, Gilmore was shot through the right lung, and wounded in the foot and leg. The back of his jacket has a hole that corresponds to the entry wound in his lung. Gilmore survived his wounds and was discharged from the army September 24, 1862. He probably kept the jacket as a memento of his harrowing experience. The state probably issued the jacket to him before his regiment left for Virginia.2

Gilmore’s jacket conforms to the Alabama State uniform specifications. It has a single row of seven buttons in front with the plumb collar edge on the buttonhole side, and a standing collar. It lacks the specified belt straps on the sides, but includes other embellishments. The fabric is a woolen-cotton, satinet weave with one woolen weft yarn over four and under two cotton warp yarns, and two cotton warp yarns over one and under two weft yarns. The very fine cotton warp ranges in color from a natural white to a light tan to a khaki. The warp has all three shades of yarn in the garment, indicating that little thought was given to maintain a uniform warp color on the looms. The woolen weft is an oatmeal-white color. The basic cloth is an overall tan color now, but it was probably steel gray before it faded. The jacket has a six-piece body, two-piece sleeves, and one-piece collar (outside). The large, jacket-size, Federal Eagle-I buttons on the front are probably replacements. The jacket was embellished with fine quality, black collar and cuff facings, and non-functional black shoulder straps. The black facings are further trimmed with worsted wool cord, and several, small Mobile Volunteer Corps buttons. The collar is lined with a heavy, plain weave, unbleached fabric, but is not “double-stayed” (top-stitched) around the edge. It also has two hooks on the right edge, and two eyelets on the left, at the top and bottom. The collar is trimmed with worsted wool cord, which only remains intact around the bottom edge. The cord is now a tannish-brown color, and its original color is unrecognizable. The pointed black cuff facings are now missing, but are clearly visible in Gilmore’s portrait. They, likewise have worsted wool cord along the top edge, and small Mobile Volunteer Corps buttons at the points, which are still intact. The non-functional shoulder straps are made from single pieces of black cloth, folded under at the edges, and flat-sewn directly to the jacket shoulders. They do not extend all the way to the collar edge, and are trimmed along the edge (excluding the base) with worsted wool cord. Each strap is embellished with three small Mobile Volunteer Corps buttons attached at the corners. The lining was only observed through damaged areas in the basic cloth, which revealed it to be unbleached osnaburg throughout. Likewise, not having seen the inside, the author has no information regarding the inside pocket. The edge of the jacket has a row medium brown thread top-stitching all around in a tight backstitch. The buttonholes are made with heavy weight medium brown thread. There are darts sewn in at the neckline for enhanced fitting, as well.3

The first details about the state’s quartermaster operation and products are found in a circular issued by Governor A.B. Moore, August 26, 1861. The circular is reproduced herein from a newspaper column:1

CIRCULAR:

To the Soldiers' Aid Societies Throughout the State,

_______

EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT,

Montgomery, Ala.,

August 26th, 1861.

Alabama has already more than twenty thousand troops in the field, and in a few weeks the number will be largely increased. The winter is rapidly approaching. Many of our soldiers are poor, and without the means of supplying themselves with clothing, except from the commutation money allowed by the Confederate Government, which may not be paid in time to supply themselves. The liberality of the citizens of the more wealthy counties, will, I am assured, in many instances, furnish the Companies from such counties. But that is not enough. There are thousands of our people engaged in this contest whose friends have not the means of supplying them. These men cannot be kept in the field without clothing, and they can only be supplied through the exertions and active benevolence of your societies. The object of this circular is to call your earnest attention to this subject, and to give that method and direction to your labors which will secure the greatest amount of efficiency. The articles which will be required for our soldiers, and to which your attention is especially requested, are chiefly, Uniform Jackets, Great Coats, and Pantaloons, of good strong cloth, of gray color, if possible to be obtained; Shirts, of flannel, or checked or striped cotton; Drawers, of woolen, or cotton-flannel, or stout osnaburgs; Woolen Socks; Gloves Shoes and Blankets.

In order to secure uniformity in the make, I have had sets of patterns cut for the uniform jacket, pantaloons, and great coat, which will be forwarded to the different Aid Societies, in all cases in which it is practicable, together with a model suit of these articles. I also give directions as to the number of each pattern which will be required, and also as to the making, which is important to follow as closely as possible.

It is most earnestly requested that each of the Aid Societies throughout the State should immediately ascertain:

1. The number of each of the articles of clothing named, which they can supply gratuitously, and for what companies, if any, they intend them.

2. The number of uniform jackets, great coats, pantaloons, drawers, shirts and gloves, in addition to those which may be furnished gratuitously, they can make during each of the months of September, and October, if supplied with the material.

This information should be given to me at the earliest possible day, with the address of the Aid Society, and the point, to which the patterns and model suits, can be forwarded by railroad and steamboat communication.

It should be remembered that the soldier can carry but a limited amount of clothing, and therefore the utmost care should be taken that the material is of the most substantial quality, and every article made as strong and durable as possible.

A.B. MOORE.

DIRECTIONS FOR MAKING CLOTHING.

Uniform Jacket: Standing collar of cloth doubled and double stayed, with osnaburg between the cloth, single-breasted, one pocket inside, on the left; one row of seven buttons, large size, on the right side stayed and sewed through; button-hole side perfectly straight from the collar down. One shoulder strap on each shoulder, from seam of sleeve to seam of collar, to button to neck of collar with small button. Two belt straps, one on each side, on bottom of jacket, on side seam, extending upwards, five inches, to button to small button. Sleeves and back to be lined with heavy osnaburgs.

Great Coat: Standing collar, doubled and stayed as uniform jacket, single-breasted, to button with seven large buttons on right side. Movable cape, to come down to elbows, to fasten to bottom of collar with six stout hooks and eyes, and to button in front with five small buttons on right side. Two straps behind, to be just covered by cape, and sewed into the side seams to tighten the coat -- one with one large button and the other with two button holes. Sleeves to be lined with heavy osnaburgs. Cape and back, and forepart of the coat twenty inches down, to be lined with checked or striped osnaburgs. Pockets as in pattern.

Pantaloons, cut full, well stayed in waist-band with double separate stay. Pockets on the side seam rather low down, to be double stayed top and bottom on the seam. Buttons to be sowed clear through. The staying for the bottom of legs, of osnaburg, to extend up eight inches, and to be sewed all round the top. The buttons on the Uniform jacket and Great Coat to be the military brass buttons. Bone buttons for the pantaloons. Button holes are to be worked with twist, coarse silk, or flax thread. The thread used for making to be grey or dark flax from No. 32 to 40.

The following are the numbers of each pattern required to be made out of each one hundred, and in that proportion of a smaller or greater number.

Pattern No. 1……………….25

" " 2……………….30

" " 3……………….25

" " 4……………….15

" " 5………………. 5.

The number of different sizes of shirts, drawers, &c., should be the same as those of the coats and pantaloons, and particular care should be taken, to sew a card with the number of the size of the pattern marked upon it, firmly to each article.

DIRECTIONS FOR PACKING AND FORWARDING.

When a sufficient number of articles are made, to send forward, they will be carefully packed in a box, the number of each article it contains marked legibly on the top, and directed to A. B. Moore, Governor, at Montgomery or Huntsville, as most convenient; to be sent by the usual mode of transportation. The expense of transportation will be paid at these points.

In all cases when the material is furnished gratuitously, and the clothing intended for any particular company, the company will be designated by the name of its Captain, giving his first name or initials, and the number of the Regiment according to the forms below:

FORMS OF DIRECTIONS.

GOV. A. B. MOORE,

Montgomery (or Huntsville.)

For Capt. ------ -----, Company,

Reg. Ala. Vol.

75 Uniform Coats,

75 Great Coats,

75 Pr. Drawers.

______________________________________

GOV. A. B. MOORE,

Montgomery (or Huntsville.)

75 Pants,

50 Shirts.

////////////////////////////////End of Circular///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

The circular provides a plethora of information about Alabama state issue uniforms to include what types of clothing was made, the construction features of clothing, materials used, types of buttons, size markings, sizes fabricated, and percentages of which sizes were to be fabricated. Some of this data can be verified by comparing two surviving Alabama State jackets that were made in 1861 against the prescribed specifications for fabrication. The two surviving jackets, as well as numerous photos, indicate that the specifications were adhered to fairly closely, and that the jackets differed only in the application of their trimmings and small buttons (features that might vary based upon availability of the aforementioned materials).

The first production, which was made by volunteer “Aid Societies”, consisted of jackets, great coats, pantaloons, shirts, drawers, socks, gloves, shoes and blankets. The governor’s office provided patterns for the jackets, great coats and pantaloons, “together with a model suit of these articles,” to ensure uniformity, and they were to be made, “of good strong cloth, of gray color, if possible…” Uniformity for the shirts, drawers and socks was less relevant.

The “Uniform Jacket’s” most salient feature was the “straight from the collar down” edge of the buttonhole side of the front, meaning that the edges of the collar and the lapel were plumb with one another, albeit the lapel described a slight arc from top to bottom. The prescribed features match closely with the two surviving jackets, which, remarkably, survive with photos of the soldiers wearing them.

The first of the two surviving jackets was owned by John Young Gilmore, Company E, 3rd Alabama Infantry. Gilmore enlisted in Mobile, April 23, 1861, and served in Virginia. He received multiple wounds at the Battle of Malvern Hill, July 1, 1862, and was mistakenly reported “mortally wounded.” At Malvern Hill, Gilmore was shot through the right lung, and wounded in the foot and leg. The back of his jacket has a hole that corresponds to the entry wound in his lung. Gilmore survived his wounds and was discharged from the army September 24, 1862. He probably kept the jacket as a memento of his harrowing experience. The state probably issued the jacket to him before his regiment left for Virginia.2

Gilmore’s jacket conforms to the Alabama State uniform specifications. It has a single row of seven buttons in front with the plumb collar edge on the buttonhole side, and a standing collar. It lacks the specified belt straps on the sides, but includes other embellishments. The fabric is a woolen-cotton, satinet weave with one woolen weft yarn over four and under two cotton warp yarns, and two cotton warp yarns over one and under two weft yarns. The very fine cotton warp ranges in color from a natural white to a light tan to a khaki. The warp has all three shades of yarn in the garment, indicating that little thought was given to maintain a uniform warp color on the looms. The woolen weft is an oatmeal-white color. The basic cloth is an overall tan color now, but it was probably steel gray before it faded. The jacket has a six-piece body, two-piece sleeves, and one-piece collar (outside). The large, jacket-size, Federal Eagle-I buttons on the front are probably replacements. The jacket was embellished with fine quality, black collar and cuff facings, and non-functional black shoulder straps. The black facings are further trimmed with worsted wool cord, and several, small Mobile Volunteer Corps buttons. The collar is lined with a heavy, plain weave, unbleached fabric, but is not “double-stayed” (top-stitched) around the edge. It also has two hooks on the right edge, and two eyelets on the left, at the top and bottom. The collar is trimmed with worsted wool cord, which only remains intact around the bottom edge. The cord is now a tannish-brown color, and its original color is unrecognizable. The pointed black cuff facings are now missing, but are clearly visible in Gilmore’s portrait. They, likewise have worsted wool cord along the top edge, and small Mobile Volunteer Corps buttons at the points, which are still intact. The non-functional shoulder straps are made from single pieces of black cloth, folded under at the edges, and flat-sewn directly to the jacket shoulders. They do not extend all the way to the collar edge, and are trimmed along the edge (excluding the base) with worsted wool cord. Each strap is embellished with three small Mobile Volunteer Corps buttons attached at the corners. The lining was only observed through damaged areas in the basic cloth, which revealed it to be unbleached osnaburg throughout. Likewise, not having seen the inside, the author has no information regarding the inside pocket. The edge of the jacket has a row medium brown thread top-stitching all around in a tight backstitch. The buttonholes are made with heavy weight medium brown thread. There are darts sewn in at the neckline for enhanced fitting, as well.3

The second surviving Alabama jacket was owned by Thomas M. Murphree, who wore it while a member of Company E, 6th Alabama Infantry. Murphree enlisted in Montgomery, May 15, 1861, and he received the jacket as part of his state clothing issue in August. He wore the jacket until February 1863, and used it at the Battle of Sharpsburg as a pillow to cradle the head of his wounded Colonel, John Brown Gordon. Remarkably, the jacket came with a note from the seamstress who made the jacket, Miss Napp, which Murphree preserved as a keepsake. Murphree was eventually commissioned, appointed as commander of Company H, 57th Alabama Infantry, and served in the Western theater for the remainder of the war. The jacket is in poor condition, with the cuffs fraying and much of the bottom part completely missing. Murphree posed for a picture in the jacket as a veteran years after the war, and the jacket reflected this poor condition therein.4

Murphree’s jacket is closer to the intent of the uniform specifications, which prescribed a simple jacket. It nonetheless had a few embellishments. It is cut from the same basic pattern as the Gilmore jacket with a seven button front, but without colored facings, and with two slanted, exterior breast pockets. There are also no darts sewn in at the neckline. The shoulder straps have remnants of worsted wool lace that is now badly faded. Due to the lower portion of the jacket being worn away, it is impossible to determine whether the jacket had belt straps. The basic fabric is a woolen-cotton jeans with one woolen weft yarn over two and under one fine cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over one weft yarns. The cotton warp is mostly a light khaki color, but the sleeves, the right side of the collar and part of the right front piece have a natural white warp. This mix of warp yarn color is consistent with that observed in the Gilmore jacket, even though each garment has a different type of fabric weave. The woolen weft is mostly an oatmeal-white color, and the overall effect of the basic cloth’s color is khaki. Fortunately, however, several patches of unexposed warp yarns remain intact and unfaded, representing the original color: steel gray. This corresponds to the prescribed uniform color. The jacket has a six-piece body, and two-piece sleeves. The collar construction was not entirely visible during the examination. The lining appears to differ from the cut of the body, having no front pieces, with the wide facing lapels and side pieces joining together. The facing lapels that line the front are woolen-cotton tabby weave cloth with a golden brown cotton warp, and a mix of pinkish-red, white and khaki weft yarns that are filled in distinct layers, giving the effect of stripes. Also, the front pieces have cotton batting interlining. The lining in the sleeves, body and right pocket bag is unbleached osnaburg, and the lining in the left pocket bag is unbleached cotton twill. The lining conforms to the prescribed construction, “Sleeves and back to be lined with heavy osnaburgs.” The back lining was not visible during the viewing, and much of it has in fact worn away, but I assume that it, too, is of osnaburg. The front jacket buttons, consisting of both CSAs and Federal staff, are later replacements. The collar appears to be unlined, but is “double-stayed” (top-stitched) around the edge. The collar may have been trimmed with worsted wool lace, as are the shoulder straps, but none remains intact. The functional shoulder straps are made by folding a single piece of jeans together and cutting the outline of the shoulder strap at the base, along one edge and at the top curve, leaving the opposite edge intact with the top and bottom sides connected. The strap is then flat sewn along the outside edge, leaving the cut, raw edges as is, and binding the entire edge (except for the base) with inch-wide wool lace, folded around the edge of the strap, top and bottom, and stitched in place. The wool lace has faded to a pale tannish-green, but was probably black originally. Each strap has a functional buttonhole and is secured with a small Federal staff button. The shoulder straps extend all the way to the base of the collar. The edge of the jacket has a row khaki-colored thread top-stitching, and the buttonholes, exterior pockets and shoulder straps are also sewn with the same thread.5

Murphree’s jacket is closer to the intent of the uniform specifications, which prescribed a simple jacket. It nonetheless had a few embellishments. It is cut from the same basic pattern as the Gilmore jacket with a seven button front, but without colored facings, and with two slanted, exterior breast pockets. There are also no darts sewn in at the neckline. The shoulder straps have remnants of worsted wool lace that is now badly faded. Due to the lower portion of the jacket being worn away, it is impossible to determine whether the jacket had belt straps. The basic fabric is a woolen-cotton jeans with one woolen weft yarn over two and under one fine cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over one weft yarns. The cotton warp is mostly a light khaki color, but the sleeves, the right side of the collar and part of the right front piece have a natural white warp. This mix of warp yarn color is consistent with that observed in the Gilmore jacket, even though each garment has a different type of fabric weave. The woolen weft is mostly an oatmeal-white color, and the overall effect of the basic cloth’s color is khaki. Fortunately, however, several patches of unexposed warp yarns remain intact and unfaded, representing the original color: steel gray. This corresponds to the prescribed uniform color. The jacket has a six-piece body, and two-piece sleeves. The collar construction was not entirely visible during the examination. The lining appears to differ from the cut of the body, having no front pieces, with the wide facing lapels and side pieces joining together. The facing lapels that line the front are woolen-cotton tabby weave cloth with a golden brown cotton warp, and a mix of pinkish-red, white and khaki weft yarns that are filled in distinct layers, giving the effect of stripes. Also, the front pieces have cotton batting interlining. The lining in the sleeves, body and right pocket bag is unbleached osnaburg, and the lining in the left pocket bag is unbleached cotton twill. The lining conforms to the prescribed construction, “Sleeves and back to be lined with heavy osnaburgs.” The back lining was not visible during the viewing, and much of it has in fact worn away, but I assume that it, too, is of osnaburg. The front jacket buttons, consisting of both CSAs and Federal staff, are later replacements. The collar appears to be unlined, but is “double-stayed” (top-stitched) around the edge. The collar may have been trimmed with worsted wool lace, as are the shoulder straps, but none remains intact. The functional shoulder straps are made by folding a single piece of jeans together and cutting the outline of the shoulder strap at the base, along one edge and at the top curve, leaving the opposite edge intact with the top and bottom sides connected. The strap is then flat sewn along the outside edge, leaving the cut, raw edges as is, and binding the entire edge (except for the base) with inch-wide wool lace, folded around the edge of the strap, top and bottom, and stitched in place. The wool lace has faded to a pale tannish-green, but was probably black originally. Each strap has a functional buttonhole and is secured with a small Federal staff button. The shoulder straps extend all the way to the base of the collar. The edge of the jacket has a row khaki-colored thread top-stitching, and the buttonholes, exterior pockets and shoulder straps are also sewn with the same thread.5

Image 17: The front of Thomas Marion Murphree’s jacket shows the same basic cut that was used for Gilmore’s jacket: seven button front, shoulder straps, a six-piece body and two piece sleeves. Artifact courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, Confederate Memorial Park, Marbury, Alabama.

Unfortunately, there are no known surviving great coats or pantaloons to compare to the regulations, but it is clear from studying the two surviving jackets that the state quartermaster provided uniforms as prescribed, and that they were steel gray in color. It is also well documented that uniforms were made in five sizes, and that the size number was marked on a card that was sewn to the garment.

Finally, nothing specifically documents the types of buttons applied to the uniforms. The surviving jackets have mostly post-war, replaced buttons. Gilmore’s jackets has small-size Mobile Volunteer Corps (MVC) buttons on the shoulder straps and cuffs that are probably original to the jacket and representative of what the large-size front buttons were. The MVC buttons were imported from the North, as were the other Alabama buttons available in 1861. Styles were few. They included the Alabama Volunteer Corps (AVC) eagle button in two variations; the Alabama state seal “map” button; and, Alabama Cadet Corps (ACC) button. The state-issue jackets probably used these types of buttons, or even Federal army buttons, until the stocks were depleted.6

Finally, nothing specifically documents the types of buttons applied to the uniforms. The surviving jackets have mostly post-war, replaced buttons. Gilmore’s jackets has small-size Mobile Volunteer Corps (MVC) buttons on the shoulder straps and cuffs that are probably original to the jacket and representative of what the large-size front buttons were. The MVC buttons were imported from the North, as were the other Alabama buttons available in 1861. Styles were few. They included the Alabama Volunteer Corps (AVC) eagle button in two variations; the Alabama state seal “map” button; and, Alabama Cadet Corps (ACC) button. The state-issue jackets probably used these types of buttons, or even Federal army buttons, until the stocks were depleted.6

Surviving state quartermaster records include the following quantities of clothing issued in 1861: 3,395 caps, 2,357 great coats, 5,147 jackets, 7,245 pants, 1,625 hats, 13,993 shirts, 7,228 drawers, 5,445 socks, and 3,793 blankets. In all likelihood, more was made and issued.7

After the first year of the war, the production of state quartermaster clothing tapered off. From the beginning of 1862 until the fourth quarter of 1864, at which point imported clothing became available, issues of domestically made clothing included approximately 2,079 great coats, 6,430 jackets, 6,673 pairs of pants, 11,503 wool hats, 16,273 cotton shirts, 1,689 flannel shirts, 15,862 pairs of cotton drawers, 10,170 pairs of cotton socks, 920 blankets, and 6,867 pairs of shoes.8

The aforementioned issued clothing presumably included that issued from the Alabama State Quartermaster office in Richmond, Virginia. This operation provided Alabama troops with 996 hats, 1,055 jackets, and 146 pairs of pants in 1861; 511 hats, 444 jackets, 206 pairs of pants, and 222 great coats in 1862; 972 hats, 6 jackets, and 299 pairs of pants in 1863; and, 419 jackets, 749 pairs of pants, and 712 great coats in 1864. This clothing would have been issued over and above what the Alabama troops were entitled to from the Confederate quartermaster.9

From 1862, the state stopped making cloth caps, having switched to manufacturing wool hats, priced at $10.00 each by the fourth quarter 1864. The quartermaster made a special order of 300 “Cadet Caps” in Montgomery, first quarter 1864, probably as an exception for a military school. During 1864, seamstresses were no longer paid to make them, and the cloth cap was dropped from the schedule of prices for clothing. By contrast, a small quantity of “Glazed Caps” were made, and 600 were issued from late 1861 through December 1862. Their list price was $1.00 in the third quarter 1862, and $1.25 in the second quarter 1863. After 115 glazed caps remained unissued for nearly a year, they were dropped from the inventory.10

Descriptions of uniforms in the quartermaster records provide clues about their clothing’s characteristics. On February 1, 1862, the schedule price for satinet pants was $3.50 compared to $2.25 for the most common type of pants that were presumably of a less expensive fabric, presumably linseys.11 In Montgomery, December 1862, the quartermaster lists “wool jackets,” and three types of pants: “unlined,” “lined,” and unspecified, (each with a different price). A May-June 1863 report includes “Grey Jacket, $8.00,” and “Grey Pants, $7.00.” This was in contrast to the usual prices of the unspecified jacket, $5.50, and pants, $5.00, which again indicated that different qualities of fabric were used. During the fourth quarter 1864, domestically manufactured jackets and pants sold for $14.00 and $12.00 each respectively.12 The pants were made with buckles on the rear adjustment belt throughout the war.13 As well as linseys and satinets, the standard wool jacket and pants were occasionally made from tweeds and jeans. Gray or dark flax thread, from No. 32 to 40, was used for making uniforms, and the uniform linings were typically made of osnaburgs.14 The evidence suggests that great coats, jackets and pants were made in the prescribed gray color, although they apparently faded quickly to butternut. The state quartermaster also used both large and small military buttons for jackets early in the war, starting with an inventory of approximately 100,000 large and 34,000 small buttons. These were presumably either Alabama Volunteer Corps eagle buttons, or Alabama seal and map buttons, or perhaps both. A residual stock of these still remained unissued in the fourth quarter 1864.15 Cotton batting may have been used in most of the jackets: it is observed in a surviving original made in 1861, and batting was still carried in the state quartermaster inventory in the first quarter 1864.16

“Linseys” were the most prevalent fabric used in making uniforms, with “satinet” used to a lesser degree. Linsey described a type of twill weave, and the term itself was archaic at the time of the Civil War. The name linsey harkened back to the pre-cotton era, when its warp was made of linen: hence the term “linsey-woolsey.” Linsey-woolsey had generally been made in a twill weave, and when the cotton warp replaced the linen, the term linsey was retained to describe the particular weave itself rather than its linen component. By the Civil War, linen warps had fallen out of use because they had to be imported, and they could not compete with the cotton warp in terms of price or availability.17

The State Quartermaster in Montgomery records three transfers of linsey cloth for jackets and pants in October and November 1861. These included a total of 5,400 yards, received in eighteen bales with 300 yards of cloth per bale. The quartermaster also reported using “Tweeds, Linseys & Kerseys” during the fourth quarter 1861, and later, in the fourth quarter 1862, “Tweeds & Jeans.”18 Evidently, Confederate quartermasters in Alabama used linsey, too, and it is from their records and surviving uniforms that more information is available.

The most salient examples of linsey fabric include that observed in the Thomas Taylor jacket, and Arthur A. Crews cap. The weave in each of these garments has one woolen weft yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over two woolen weft yarns.19 The identification of this weave as “linsey” is made through the Thomas Taylor jacket. Thomas Taylor, detailed in Montgomery from the 8th Louisiana Infantry, purchased there on November 24, 1863 eight yards of “Linsey,” along with nine yards of shirting and seven yards of drilling. He used the linsey as the basic fabric; the brown striped shirting as the body lining; and, the unbleached drilling for the sleeve lining. His surviving jacket allows a comparison of its weave to the quartermaster’s description, and to the same weave in other garments with provenance to the region. Taylor’s jacket has a natural white cotton warp and a steel gray woolen weft, possibly undyed sheep’s gray. The overall fabric color appears steel gray.20

After the first year of the war, the production of state quartermaster clothing tapered off. From the beginning of 1862 until the fourth quarter of 1864, at which point imported clothing became available, issues of domestically made clothing included approximately 2,079 great coats, 6,430 jackets, 6,673 pairs of pants, 11,503 wool hats, 16,273 cotton shirts, 1,689 flannel shirts, 15,862 pairs of cotton drawers, 10,170 pairs of cotton socks, 920 blankets, and 6,867 pairs of shoes.8

The aforementioned issued clothing presumably included that issued from the Alabama State Quartermaster office in Richmond, Virginia. This operation provided Alabama troops with 996 hats, 1,055 jackets, and 146 pairs of pants in 1861; 511 hats, 444 jackets, 206 pairs of pants, and 222 great coats in 1862; 972 hats, 6 jackets, and 299 pairs of pants in 1863; and, 419 jackets, 749 pairs of pants, and 712 great coats in 1864. This clothing would have been issued over and above what the Alabama troops were entitled to from the Confederate quartermaster.9

From 1862, the state stopped making cloth caps, having switched to manufacturing wool hats, priced at $10.00 each by the fourth quarter 1864. The quartermaster made a special order of 300 “Cadet Caps” in Montgomery, first quarter 1864, probably as an exception for a military school. During 1864, seamstresses were no longer paid to make them, and the cloth cap was dropped from the schedule of prices for clothing. By contrast, a small quantity of “Glazed Caps” were made, and 600 were issued from late 1861 through December 1862. Their list price was $1.00 in the third quarter 1862, and $1.25 in the second quarter 1863. After 115 glazed caps remained unissued for nearly a year, they were dropped from the inventory.10

Descriptions of uniforms in the quartermaster records provide clues about their clothing’s characteristics. On February 1, 1862, the schedule price for satinet pants was $3.50 compared to $2.25 for the most common type of pants that were presumably of a less expensive fabric, presumably linseys.11 In Montgomery, December 1862, the quartermaster lists “wool jackets,” and three types of pants: “unlined,” “lined,” and unspecified, (each with a different price). A May-June 1863 report includes “Grey Jacket, $8.00,” and “Grey Pants, $7.00.” This was in contrast to the usual prices of the unspecified jacket, $5.50, and pants, $5.00, which again indicated that different qualities of fabric were used. During the fourth quarter 1864, domestically manufactured jackets and pants sold for $14.00 and $12.00 each respectively.12 The pants were made with buckles on the rear adjustment belt throughout the war.13 As well as linseys and satinets, the standard wool jacket and pants were occasionally made from tweeds and jeans. Gray or dark flax thread, from No. 32 to 40, was used for making uniforms, and the uniform linings were typically made of osnaburgs.14 The evidence suggests that great coats, jackets and pants were made in the prescribed gray color, although they apparently faded quickly to butternut. The state quartermaster also used both large and small military buttons for jackets early in the war, starting with an inventory of approximately 100,000 large and 34,000 small buttons. These were presumably either Alabama Volunteer Corps eagle buttons, or Alabama seal and map buttons, or perhaps both. A residual stock of these still remained unissued in the fourth quarter 1864.15 Cotton batting may have been used in most of the jackets: it is observed in a surviving original made in 1861, and batting was still carried in the state quartermaster inventory in the first quarter 1864.16

“Linseys” were the most prevalent fabric used in making uniforms, with “satinet” used to a lesser degree. Linsey described a type of twill weave, and the term itself was archaic at the time of the Civil War. The name linsey harkened back to the pre-cotton era, when its warp was made of linen: hence the term “linsey-woolsey.” Linsey-woolsey had generally been made in a twill weave, and when the cotton warp replaced the linen, the term linsey was retained to describe the particular weave itself rather than its linen component. By the Civil War, linen warps had fallen out of use because they had to be imported, and they could not compete with the cotton warp in terms of price or availability.17

The State Quartermaster in Montgomery records three transfers of linsey cloth for jackets and pants in October and November 1861. These included a total of 5,400 yards, received in eighteen bales with 300 yards of cloth per bale. The quartermaster also reported using “Tweeds, Linseys & Kerseys” during the fourth quarter 1861, and later, in the fourth quarter 1862, “Tweeds & Jeans.”18 Evidently, Confederate quartermasters in Alabama used linsey, too, and it is from their records and surviving uniforms that more information is available.

The most salient examples of linsey fabric include that observed in the Thomas Taylor jacket, and Arthur A. Crews cap. The weave in each of these garments has one woolen weft yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over two woolen weft yarns.19 The identification of this weave as “linsey” is made through the Thomas Taylor jacket. Thomas Taylor, detailed in Montgomery from the 8th Louisiana Infantry, purchased there on November 24, 1863 eight yards of “Linsey,” along with nine yards of shirting and seven yards of drilling. He used the linsey as the basic fabric; the brown striped shirting as the body lining; and, the unbleached drilling for the sleeve lining. His surviving jacket allows a comparison of its weave to the quartermaster’s description, and to the same weave in other garments with provenance to the region. Taylor’s jacket has a natural white cotton warp and a steel gray woolen weft, possibly undyed sheep’s gray. The overall fabric color appears steel gray.20

The state quartermaster records do not mention the name or location of the factories that made its basic uniform cloth. However, Confederate quartermasters remarked on March 15, 1864 that the Selma and Montgomery, Alabama facilities procured most of their “very substantial cloth for pants and jackets” from the Tallassee mill of Tallapoosa County, as well as “cotton goods, drillings, etc.” The state quartermaster might have used Tallassee mill for its basic uniform cloth, as well. The state quartermaster drew on the Prattville factory for cotton cloth, and probably the Tallassee mill, too.21 It is worth noting that the Tallassee mill made “drillings,” the mill where Thomas Taylor’s jacket drillings may have come from.

Domestically made great coats, or over coats, were made of the same basic materials as the jackets and pants. In 1861, they were made with military brass buttons, but by the first quarter of 1862, the quartermaster put bone buttons on them. The names “Great Coat” and “Over Coat” referred to the same garment, but different records used different names. Quarterly returns, transfers and the governor’s circular called them “Great Coats.” Price lists, payments and sales called the “Over Coats.” The linings were officially prescribed as heavy osnaburgs for the sleeves, and “checked or striped” osnaburgs in the cape and body. In Mobile, 1862, great coat linings were made from Silesia, osnaburgs, and denims. In December 1862, they were priced at $10.00 each, and “Over Coat Capes” at $12.00 each. The latter term is not entirely clear.22

Shirts and drawers were typically made of osnaburgs. To a lesser extent, flannel shirts and drawers were also made throughout the war. Until the end of 1862, the state also made “hickory” shirts, and in Mobile, the quartermaster used “Lowells” (distinct from osnaburgs) to make cotton shirts. In December 1862, the quartermaster provided some descriptions by listing a “white cotton shirt;” a “brn” [brown] over shirt; and, flannel shirts, either “red” or unspecified. The unspecified listing is presumably white, since both red and white flannel were for sale by the yard on the same list.23

The quartermaster shoe was described in December 1862 in three ways: “Army Shoes (Brogs) $7.00;” “Kip Brogs $6.00,” and, unspecified ranging from $4.50 to $6.00. The different prices per pair indicate different qualities. In an August 1862 record, shoes were described as, “Shoes Tap S, pair, $3.50.” The quartermaster expended shoe pegs during the third quarter 1864, and priced “Pegged Shoes” at $20.00 a pair in the fourth quarter, which indicates that the Alabama soldier shoe was pegged, rather than sewed.24

Late in the war, the quartermaster produced enameled capes, also listed as “capes” or “oil cloth capes.” In the fourth quarter 1864, these were priced at $40.00 each. This was presumably a poncho or enameled ground cloth similar to that issued to Federal soldiers.25

The Alabama quartermaster also listed such articles as wool socks, gloves, neck ties and carpet blankets but very few of these were issued.

Alabama did not limit its quartermaster issues to its home industry production alone. Early in 1864, the state contracted with Peter Tait & Company of Limerick, Ireland for a delivery of clothing. Regrettably, the contract is lost, so the exact specifications for, and quantities of clothing are unavailable. Fortunately, subsequent quartermaster documents and a newspaper article provide approximate descriptions. Quantities can only be estimated from fragmentary records of issues and sales during the fourth quarter of 1864. In any case, the State of Alabama paid James L. Tait, the company’s agent, $427,509.00 in three installments on January 18, February 15 and March 6, 1865. Tait undoubtedly received his payment in cotton or gold, but the state expenditure reflects the equivalent Confederate currency value. The sum in Confederate dollars amounted to approximately $17,100.00 in gold.26 Comparing existing records and descriptions, the contract closely mirrored a proposal that James L. Tait made to the Confederate government in December 1863, but that was rejected for being overpriced. He apparently had better luck with the State of Alabama shortly thereafter. The original Confederate proposal offered ready-cut sets of various articles, rather than ready-made clothing. Tait’s ready-cut sets of clothing had to be assembled (sewn together) by the buyer. The original proposal included:

“To be ready for shipment in 3 months from 1st January 1864

50,000 Caps ready cut (Grey Cloth) with peak 1/6 ea [1 shilling/6 pence]

50,000 Great Coats of Stout Grey Cloth cut ready for Sewing (fast dye) 12/- ea

50,000 Suits of Stout Grey Cloth Consisting of Jackets and trowsers

Cut ready for sewing (fast dye) 16/- per suit

50,000 Strong Grey Flannel Shirts cut ready for Sewing 4/- ea

50,000 pairs Army Blankets 5/6- ea

100,000 pairs Army Boots (Ankle Blucher) 10/6 ea

100,000 pairs Strong Woolen Stockings 1/- ea

50,000 Haversacks 1/6- ea

Total Amount £158,475 Sterlg [pounds]

The clothing to be cut according to the Size Rolls in use in the British Service to fit men from 5 feet 6 inches to 6 feet. [See Table 1]

The quality of all the supplies would be those in use in the British Army and subjected to the same rigid inspection.”27

The Alabama State Quartermaster accepted a modified version of this proposal, retaining the ready-cuts sets in lieu of ready-made clothing, omitting some of the articles, and adding others. The contract retained the ready-cut kits for jackets, pants and overcoats, as well as finished shoes and blankets. It apparently omitted the caps, haversacks, woolen stockings and flannel shirts, having never listed any of these articles in its inventories. Cadet gray cloth, in fine and coarse grades, appears to have been added to the final contract, judging from the prolific sales of this cloth by the Alabama quartermaster from late 1864 onwards. The contract was delivered to Wilmington, in two separate shipments, during the months from June through September 1864. From there, it was freighted by rail to Alabama, where the pre-cut clothing sets were assembled and made ready for issue by October 1864. An article from the Columbus, Georgia Daily Enquirer (dated October 22, 1864), stated in a report taken from the Montgomery Mail, provides details about the Tait uniforms:28

“Good News for Alabama Soldiers. Four months ago a contract was entered into between the State of Alabama on the part of the Quartermaster General, and the firm of Peter Tait & Co., Limerick, Ireland, through Major J.L. Tait, of the British Army, for a large quantity of military clothing for the Alabama Soldiers. Quartermaster General Green [Duff C. Green, was the Quartermaster General for the State of Alabama] stipulated that a large portion of the goods should be furnished partially cut, with the necessary trimmings, thus affording employment to the seamstresses and tailors of our home factories. Some thousands of these uniforms, we are glad to be able to announce, have arrived safely in the Confederacy, and the residue of the order is hourly expected. The outfit consists of jacket, pants, shoes and overcoat, all made of the most substantial material – the cloth being exactly the same as used in the British Army.

“The house of Peter Tait and Co. in Limerick is one of the most extensive in Great Britain, and these enterprising factors furnish a great portion of the outfit to the British army than any other in the realm, and give employment to two thousand operatives. Their own vessels run into the Confederate ports and they have filed frequent contracts with the government. Their contract with the State of Alabama has been faithfully and promptly fulfilled, thanks to the energy and tact of their agent and representative, Maj. Tait.

“Some of the goods for our state troops is [sic] already made up into Uniforms. A specimen overcoat which we have seen exhibits the superiority of the material for durability and comfort and the excellence of the make up. When Alabama’s soldiers are comfortably clad in the ample folds of a cape and skirt of one of these overcoats they will be as handsomely and as comfortably uniformed as any soldier in the world. Several thousand of these uniforms are already here. The rest of the order will be here in a few days. Montgomery Mail.”

Other accounts substantiate the Montgomery Mail’s report. Confederate Nurse, Kate Cumming, wrote on February 26, 1865, in Mobile, Alabama:

“The city [Mobile] is filled with the veterans of many battles. I have attended several of the parties, and at them the gray jackets were conspicuous. A few were in citizen’s clothes, but it was because they had lost their uniforms.

“The Alabama troops are dressed so fine that we scarcely recognize them. A large steamer, laden with clothes, ran the blockade lately, from Limerick, Ireland.”29

A Confederate deserter’s observations echo those of Kate Cumming’s. William Ross of the 2nd Alabama Battalion, speaking of Rice’s and Huger’s Brigades of Alabama Reserves, told Federal authorities on January 23, 1865, “These troops are pretty well armed, well clothed with a late importation of gray suits from England.”30

While the exact number of Tait uniforms delivered to Alabama is unknown, minimum estimates can be determined from what was issued during the fourth quarter 1864. This included at least 2,009 great coats; 1,754 jackets; 1,599 pairs of pants; 50 gross of jacket buttons (7,200 buttons); 1,740 pairs of shoes; 120 blankets; 83 yards of fine, officer grade “Grey Cloth;” and, 1,551 yards of coarse, enlisted grade “Grey Cloth.”31 More would have been issued in 1865. Using other contracts for imported clothing as a guide, it is reasonable to assume that the clothing shipped would have been sent in evenly matched sets by article and quantity. For example, a typical contract would have included specifications along these lines: “…5,000 sets of jacket, pants, great coat, shoes and blankets, along with buttons and trimmings; 4,000 yards fine Grey Cloth; 10,000 yards coarse Grey Cloth.”

The schedule of prices for the Tait articles was far more expensive than their domestic counterparts. The following comparison reflects this:32

Schedule of Prices, Alabama Quartermaster, November-December 1864

Jacket, Tait: $80.00

Jacket, Linsey: $14.00

Pants, Tait: $60.00

Pants, Satinet: $12.00

English Army Shoes, Pair: $50.00

Pegged Shoes, Pair: $20.00

Great Coat, Tait: $130.00

Great Coat, [domestically manufactured]: none in schedule of prices

Hat, Imported: none imported

Wool Hat, [domestically manufactured]: $10.00

English Blanket: $45.00

Enamel Cape, [domestically manufactured]: $40.00

Grey Cloth [fine, officer grade, cadet gray]: $22.00 per yard

Grey Cloth [coarse, enlisted grade, cadet gray]: $10.00 per yard

Domestic Linsey or Satinet: none in schedule of prices

The State of Alabama intended the Tait uniforms specifically for Alabama troops, whether in State or Confederate service. Reports suggest that the Alabama contingent at Mobile was well clothed in Tait suits by February 1865, which amounted to approximately 5,700 troops.33 Besides the Alabama troops in Mobile, many Alabamians drew Tait uniforms in Montgomery, and elsewhere, presumably.

Fortunately, examples of the cadet gray, Alabama Tait contract jacket and pants survive, and corroborate available archival evidence. Private Henry “Harry” Pillans, Company H, 62nd Alabama Infantry (1st Alabama State Reserves) owned thejacket.34 The pants are attributed to Jesse Bryant Beck, Company A, 25th Alabama Infantry.35 Since the jacket is trimmed for infantry in royal blue and the pants for artillery in bright red, it appears that Alabama received both infantry and artillery uniforms from Peter Tait & Company.

Henry Pillans enlisted on July 12, 1864 at Camp Preston, and was immediately put on detached service with the Engineer Department in Mobile. He spent his entire service in Mobile, surrendered at Citronelle, Alabama on May 4, 1865, and was paroled at Meridian, Mississippi, May 10, 1865. He received his Tait jacket during this service.

The jacket was assembled by Alabama seamstresses from a pre-cut Tait set, and it differed somewhat from the ready-made Tait jacket. The ready-made jacket followed the standard British army design but was made of Confederate gray: a dark, blue gray kersey. The jacket had two-piece sleeves, a five-piece body (two fronts, two sides and a single back piece), a one-piece outer collar with a two-piece inside facing, eight brass buttons fastening the front, and an unbleached white, heavy linen lining, the latter being common to Ireland. The lining had a black, ink-stamped marking indicating the size just below the collar. Tait made his jackets in four slight variations as to trim and shoulder straps, and he used two colors for branch-of-service trim: royal blue for infantry and red for artillery, and buttons with either “I” or “A,” corresponding likewise to the two branches of service. Pillans’s jacket conforms roughly to the variant with royal blue, infantry trim on the collar and shoulder straps.36

Because the Alabama contract jackets were assembled entirely hand-sewn from pre-cut sets that were intended to be made largely on machines, various differences are evidence. With no machine stitching, the Alabama Tait jackets are topstitched with a heavy, medium brown thread in a widely-spaced basting stitch around the edge of the collar, and along the front edges to as far as where the facing lapel meets the lining at the bottom edge of the jacket. The bottom front is also finished with curved instead of squared lapels. The most salient difference with the pre-made Tait jacket, however, is the reduced number of buttons on the front. While the pre-cut set was intended to close with eight buttons in front, the Alabama quartermaster reduced that number to five. Perhaps, this was done to conserve buttons. Interestingly, four buttons were added to the front after it was issued, bringing the front closure to nine buttons. Other minor changes to the original Tait pattern are also noticeable. The shoulder straps have small holes cut for the button shanks instead of functional buttonholes. The Richmond Depot also employed this expedience in making shoulder straps for its jackets. The lining also differs from Tait’s ready-made lining. It has a six-piece construction, which is the result of economizing by using smaller pieces of cloth to make the back lining pieces. The jacket has two inside breast pockets, a feature noted in a few of the ready-made Tait jackets, instead of a single, left lapel pocket. One of the most notable differences between the Alabama-made and the ready-made jackets is the way the interior lining is joined to the exterior body. The ready-made jacket shell and lining components were joined by laying them together back-side of the cloth facing each other, folding the raw edges of the kersey over the linen lining, and overhand-stitching the seams closed. The facing lapels were likewise whip stitched to the lining with the lining tucked under and the raw edge of the lapel facing exposed. The Alabama-made jackets were joined more like Southern depot jackets. The outside shell and the interior lining were laid together top-sides of the cloth facing each other, and sewn closed with an interior seam along the edge. The joined seam could then be clipped, the jacket turned right side out and the seams pressed flat. This method has been employed along the bottom edge of the jacket where there was enough seam allowance to permit it. However, the front edges of the lapels could not be sewn in this manner since the pieces had been cut without a seam allowance. They had to be sewn flat with a raw edge. Therefore, these edges were basted closed in similar fashion to the ready-made Tait jackets. In addition, the lining and facing lapels are closed with an interior seam, rather than the exterior, overhand-stitched closure of the ready-made jackets. The ready-made Tait jackets had a hook and eyelet closure that was omitted in the Alabama Tait. The ready-made Tait jacket had shoulder straps with the top, facing pieces cut raw, but with the bottom piece edges turned inward. The Alabama-made shoulder straps were raw cut and flat sewn, top and bottom. The interior collar facing of both the ready-made and Alabama jackets was cut raw along the top edge, but the ready-made collar facing was laid over the lining and overhand stitched in place, flat with a raw edge. The Alabama collar facing was tucked under the lining, itself folded under at the edge and then whip stitched in place. The ready-made Tait jackets were produced in standardized British army sizes and clearly marked with the size in the lining, but the Alabama Tait jackets had no size stamps. The original buttons are of an unknown type, since the buttons now on the jacket are replacements: Federal, Eagle “I” buttons. Presumably, the jacket sets came with Tait-style “I” or “A” buttons.37

Domestically made great coats, or over coats, were made of the same basic materials as the jackets and pants. In 1861, they were made with military brass buttons, but by the first quarter of 1862, the quartermaster put bone buttons on them. The names “Great Coat” and “Over Coat” referred to the same garment, but different records used different names. Quarterly returns, transfers and the governor’s circular called them “Great Coats.” Price lists, payments and sales called the “Over Coats.” The linings were officially prescribed as heavy osnaburgs for the sleeves, and “checked or striped” osnaburgs in the cape and body. In Mobile, 1862, great coat linings were made from Silesia, osnaburgs, and denims. In December 1862, they were priced at $10.00 each, and “Over Coat Capes” at $12.00 each. The latter term is not entirely clear.22

Shirts and drawers were typically made of osnaburgs. To a lesser extent, flannel shirts and drawers were also made throughout the war. Until the end of 1862, the state also made “hickory” shirts, and in Mobile, the quartermaster used “Lowells” (distinct from osnaburgs) to make cotton shirts. In December 1862, the quartermaster provided some descriptions by listing a “white cotton shirt;” a “brn” [brown] over shirt; and, flannel shirts, either “red” or unspecified. The unspecified listing is presumably white, since both red and white flannel were for sale by the yard on the same list.23

The quartermaster shoe was described in December 1862 in three ways: “Army Shoes (Brogs) $7.00;” “Kip Brogs $6.00,” and, unspecified ranging from $4.50 to $6.00. The different prices per pair indicate different qualities. In an August 1862 record, shoes were described as, “Shoes Tap S, pair, $3.50.” The quartermaster expended shoe pegs during the third quarter 1864, and priced “Pegged Shoes” at $20.00 a pair in the fourth quarter, which indicates that the Alabama soldier shoe was pegged, rather than sewed.24

Late in the war, the quartermaster produced enameled capes, also listed as “capes” or “oil cloth capes.” In the fourth quarter 1864, these were priced at $40.00 each. This was presumably a poncho or enameled ground cloth similar to that issued to Federal soldiers.25

The Alabama quartermaster also listed such articles as wool socks, gloves, neck ties and carpet blankets but very few of these were issued.

Alabama did not limit its quartermaster issues to its home industry production alone. Early in 1864, the state contracted with Peter Tait & Company of Limerick, Ireland for a delivery of clothing. Regrettably, the contract is lost, so the exact specifications for, and quantities of clothing are unavailable. Fortunately, subsequent quartermaster documents and a newspaper article provide approximate descriptions. Quantities can only be estimated from fragmentary records of issues and sales during the fourth quarter of 1864. In any case, the State of Alabama paid James L. Tait, the company’s agent, $427,509.00 in three installments on January 18, February 15 and March 6, 1865. Tait undoubtedly received his payment in cotton or gold, but the state expenditure reflects the equivalent Confederate currency value. The sum in Confederate dollars amounted to approximately $17,100.00 in gold.26 Comparing existing records and descriptions, the contract closely mirrored a proposal that James L. Tait made to the Confederate government in December 1863, but that was rejected for being overpriced. He apparently had better luck with the State of Alabama shortly thereafter. The original Confederate proposal offered ready-cut sets of various articles, rather than ready-made clothing. Tait’s ready-cut sets of clothing had to be assembled (sewn together) by the buyer. The original proposal included:

“To be ready for shipment in 3 months from 1st January 1864

50,000 Caps ready cut (Grey Cloth) with peak 1/6 ea [1 shilling/6 pence]

50,000 Great Coats of Stout Grey Cloth cut ready for Sewing (fast dye) 12/- ea

50,000 Suits of Stout Grey Cloth Consisting of Jackets and trowsers

Cut ready for sewing (fast dye) 16/- per suit

50,000 Strong Grey Flannel Shirts cut ready for Sewing 4/- ea

50,000 pairs Army Blankets 5/6- ea

100,000 pairs Army Boots (Ankle Blucher) 10/6 ea

100,000 pairs Strong Woolen Stockings 1/- ea

50,000 Haversacks 1/6- ea

Total Amount £158,475 Sterlg [pounds]

The clothing to be cut according to the Size Rolls in use in the British Service to fit men from 5 feet 6 inches to 6 feet. [See Table 1]

The quality of all the supplies would be those in use in the British Army and subjected to the same rigid inspection.”27

The Alabama State Quartermaster accepted a modified version of this proposal, retaining the ready-cuts sets in lieu of ready-made clothing, omitting some of the articles, and adding others. The contract retained the ready-cut kits for jackets, pants and overcoats, as well as finished shoes and blankets. It apparently omitted the caps, haversacks, woolen stockings and flannel shirts, having never listed any of these articles in its inventories. Cadet gray cloth, in fine and coarse grades, appears to have been added to the final contract, judging from the prolific sales of this cloth by the Alabama quartermaster from late 1864 onwards. The contract was delivered to Wilmington, in two separate shipments, during the months from June through September 1864. From there, it was freighted by rail to Alabama, where the pre-cut clothing sets were assembled and made ready for issue by October 1864. An article from the Columbus, Georgia Daily Enquirer (dated October 22, 1864), stated in a report taken from the Montgomery Mail, provides details about the Tait uniforms:28

“Good News for Alabama Soldiers. Four months ago a contract was entered into between the State of Alabama on the part of the Quartermaster General, and the firm of Peter Tait & Co., Limerick, Ireland, through Major J.L. Tait, of the British Army, for a large quantity of military clothing for the Alabama Soldiers. Quartermaster General Green [Duff C. Green, was the Quartermaster General for the State of Alabama] stipulated that a large portion of the goods should be furnished partially cut, with the necessary trimmings, thus affording employment to the seamstresses and tailors of our home factories. Some thousands of these uniforms, we are glad to be able to announce, have arrived safely in the Confederacy, and the residue of the order is hourly expected. The outfit consists of jacket, pants, shoes and overcoat, all made of the most substantial material – the cloth being exactly the same as used in the British Army.

“The house of Peter Tait and Co. in Limerick is one of the most extensive in Great Britain, and these enterprising factors furnish a great portion of the outfit to the British army than any other in the realm, and give employment to two thousand operatives. Their own vessels run into the Confederate ports and they have filed frequent contracts with the government. Their contract with the State of Alabama has been faithfully and promptly fulfilled, thanks to the energy and tact of their agent and representative, Maj. Tait.

“Some of the goods for our state troops is [sic] already made up into Uniforms. A specimen overcoat which we have seen exhibits the superiority of the material for durability and comfort and the excellence of the make up. When Alabama’s soldiers are comfortably clad in the ample folds of a cape and skirt of one of these overcoats they will be as handsomely and as comfortably uniformed as any soldier in the world. Several thousand of these uniforms are already here. The rest of the order will be here in a few days. Montgomery Mail.”

Other accounts substantiate the Montgomery Mail’s report. Confederate Nurse, Kate Cumming, wrote on February 26, 1865, in Mobile, Alabama:

“The city [Mobile] is filled with the veterans of many battles. I have attended several of the parties, and at them the gray jackets were conspicuous. A few were in citizen’s clothes, but it was because they had lost their uniforms.

“The Alabama troops are dressed so fine that we scarcely recognize them. A large steamer, laden with clothes, ran the blockade lately, from Limerick, Ireland.”29

A Confederate deserter’s observations echo those of Kate Cumming’s. William Ross of the 2nd Alabama Battalion, speaking of Rice’s and Huger’s Brigades of Alabama Reserves, told Federal authorities on January 23, 1865, “These troops are pretty well armed, well clothed with a late importation of gray suits from England.”30

While the exact number of Tait uniforms delivered to Alabama is unknown, minimum estimates can be determined from what was issued during the fourth quarter 1864. This included at least 2,009 great coats; 1,754 jackets; 1,599 pairs of pants; 50 gross of jacket buttons (7,200 buttons); 1,740 pairs of shoes; 120 blankets; 83 yards of fine, officer grade “Grey Cloth;” and, 1,551 yards of coarse, enlisted grade “Grey Cloth.”31 More would have been issued in 1865. Using other contracts for imported clothing as a guide, it is reasonable to assume that the clothing shipped would have been sent in evenly matched sets by article and quantity. For example, a typical contract would have included specifications along these lines: “…5,000 sets of jacket, pants, great coat, shoes and blankets, along with buttons and trimmings; 4,000 yards fine Grey Cloth; 10,000 yards coarse Grey Cloth.”

The schedule of prices for the Tait articles was far more expensive than their domestic counterparts. The following comparison reflects this:32

Schedule of Prices, Alabama Quartermaster, November-December 1864

Jacket, Tait: $80.00

Jacket, Linsey: $14.00

Pants, Tait: $60.00

Pants, Satinet: $12.00

English Army Shoes, Pair: $50.00

Pegged Shoes, Pair: $20.00

Great Coat, Tait: $130.00

Great Coat, [domestically manufactured]: none in schedule of prices

Hat, Imported: none imported

Wool Hat, [domestically manufactured]: $10.00

English Blanket: $45.00

Enamel Cape, [domestically manufactured]: $40.00

Grey Cloth [fine, officer grade, cadet gray]: $22.00 per yard

Grey Cloth [coarse, enlisted grade, cadet gray]: $10.00 per yard

Domestic Linsey or Satinet: none in schedule of prices

The State of Alabama intended the Tait uniforms specifically for Alabama troops, whether in State or Confederate service. Reports suggest that the Alabama contingent at Mobile was well clothed in Tait suits by February 1865, which amounted to approximately 5,700 troops.33 Besides the Alabama troops in Mobile, many Alabamians drew Tait uniforms in Montgomery, and elsewhere, presumably.

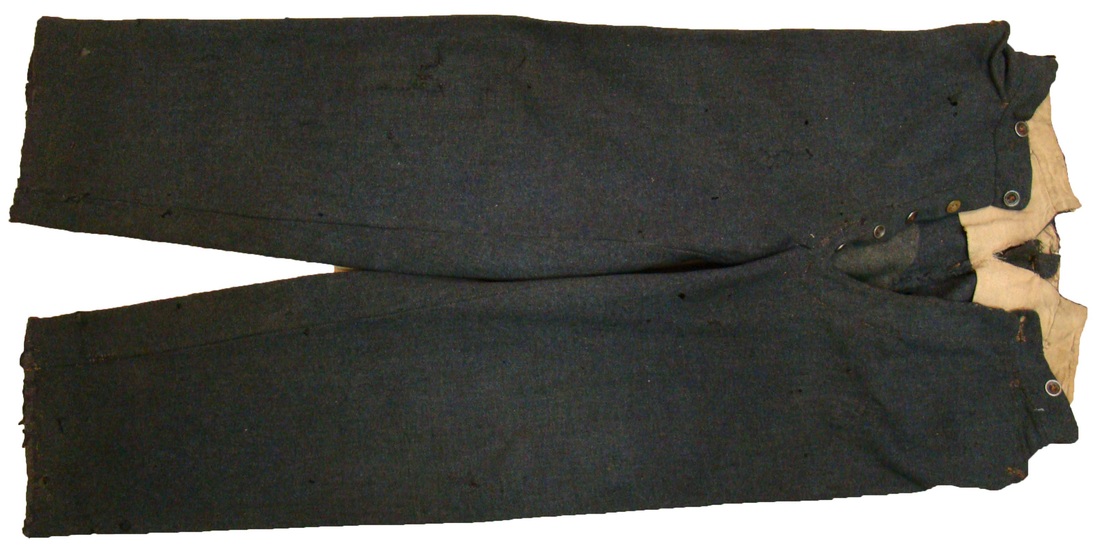

Fortunately, examples of the cadet gray, Alabama Tait contract jacket and pants survive, and corroborate available archival evidence. Private Henry “Harry” Pillans, Company H, 62nd Alabama Infantry (1st Alabama State Reserves) owned thejacket.34 The pants are attributed to Jesse Bryant Beck, Company A, 25th Alabama Infantry.35 Since the jacket is trimmed for infantry in royal blue and the pants for artillery in bright red, it appears that Alabama received both infantry and artillery uniforms from Peter Tait & Company.

Henry Pillans enlisted on July 12, 1864 at Camp Preston, and was immediately put on detached service with the Engineer Department in Mobile. He spent his entire service in Mobile, surrendered at Citronelle, Alabama on May 4, 1865, and was paroled at Meridian, Mississippi, May 10, 1865. He received his Tait jacket during this service.

The jacket was assembled by Alabama seamstresses from a pre-cut Tait set, and it differed somewhat from the ready-made Tait jacket. The ready-made jacket followed the standard British army design but was made of Confederate gray: a dark, blue gray kersey. The jacket had two-piece sleeves, a five-piece body (two fronts, two sides and a single back piece), a one-piece outer collar with a two-piece inside facing, eight brass buttons fastening the front, and an unbleached white, heavy linen lining, the latter being common to Ireland. The lining had a black, ink-stamped marking indicating the size just below the collar. Tait made his jackets in four slight variations as to trim and shoulder straps, and he used two colors for branch-of-service trim: royal blue for infantry and red for artillery, and buttons with either “I” or “A,” corresponding likewise to the two branches of service. Pillans’s jacket conforms roughly to the variant with royal blue, infantry trim on the collar and shoulder straps.36