Confederate Depot Uniforms of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, 1864-1865, Part III: The Pants, Caps and Hats of Department's Depots, and the Cadet Gray Uniforms of Mobile, Alabama

By Frederick R. Adolphus, June 12, 2016; Updated October 5, 2016

By Frederick R. Adolphus, June 12, 2016; Updated October 5, 2016

Continued from Part II: click here to navigate back to the previous page...

At least four pairs of pants have survived with provenance to the department: some accompanying Anderson or Montgomery jackets, and some alone. Taken as a whole, they do not conform to distinctive typologies. They do, however, share some traits that might reasonably associate them with one another or with the department’s quartermaster operations. In any case, assigning the trousers to one depot or the other, or linking them with each other is tenuous. This part of the study closely examines the surviving trousers’ provenance, tailoring, buttons, color, fabric and weave to surmise their origin.

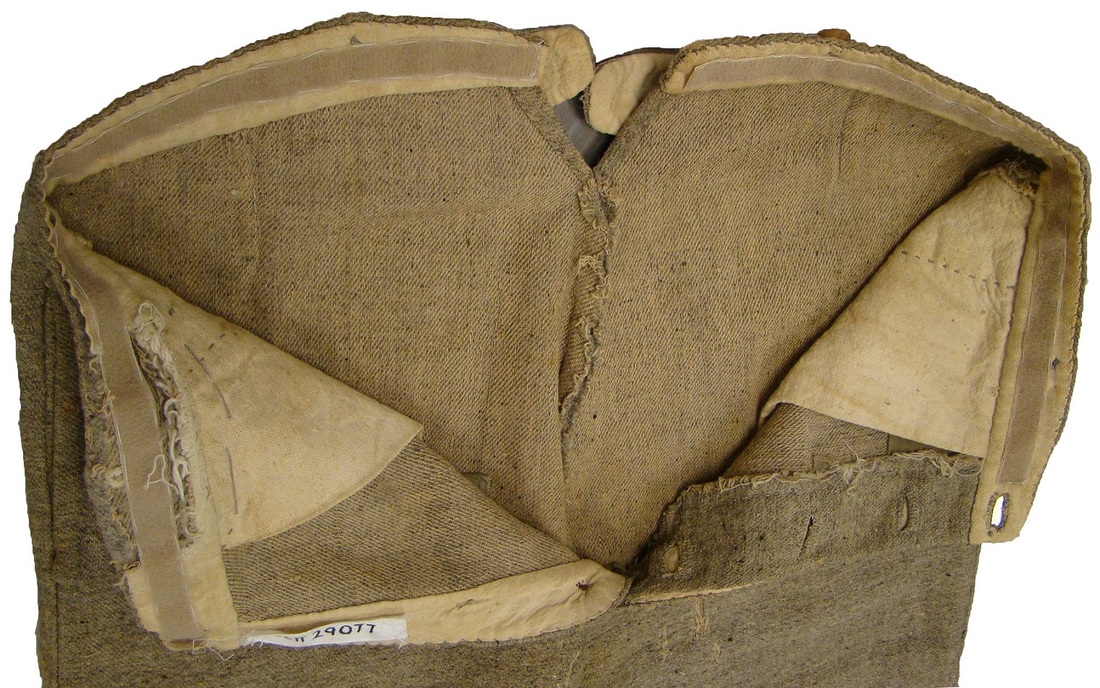

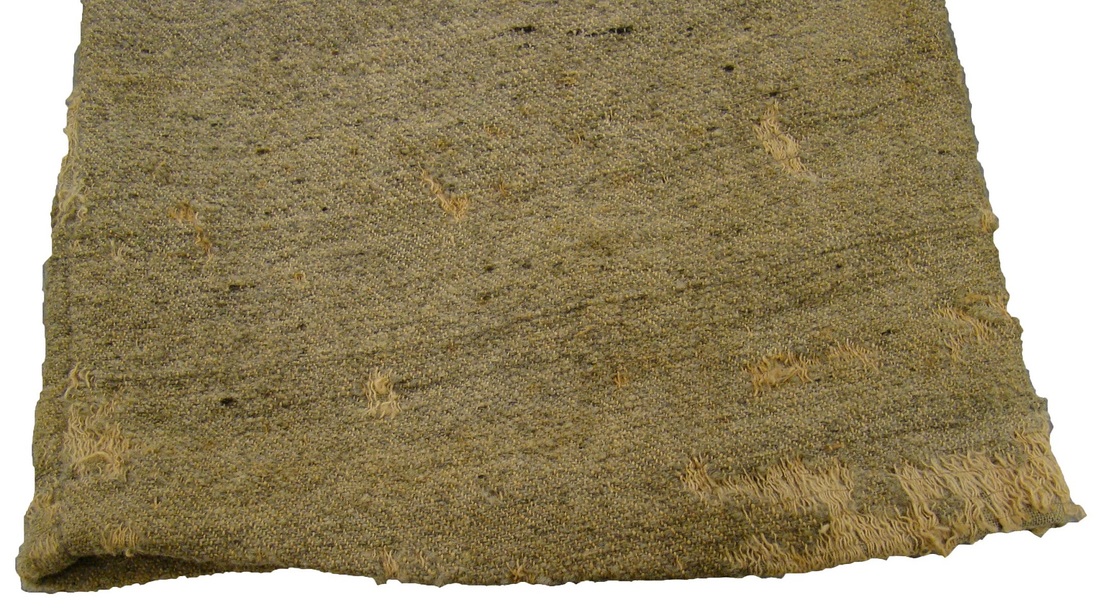

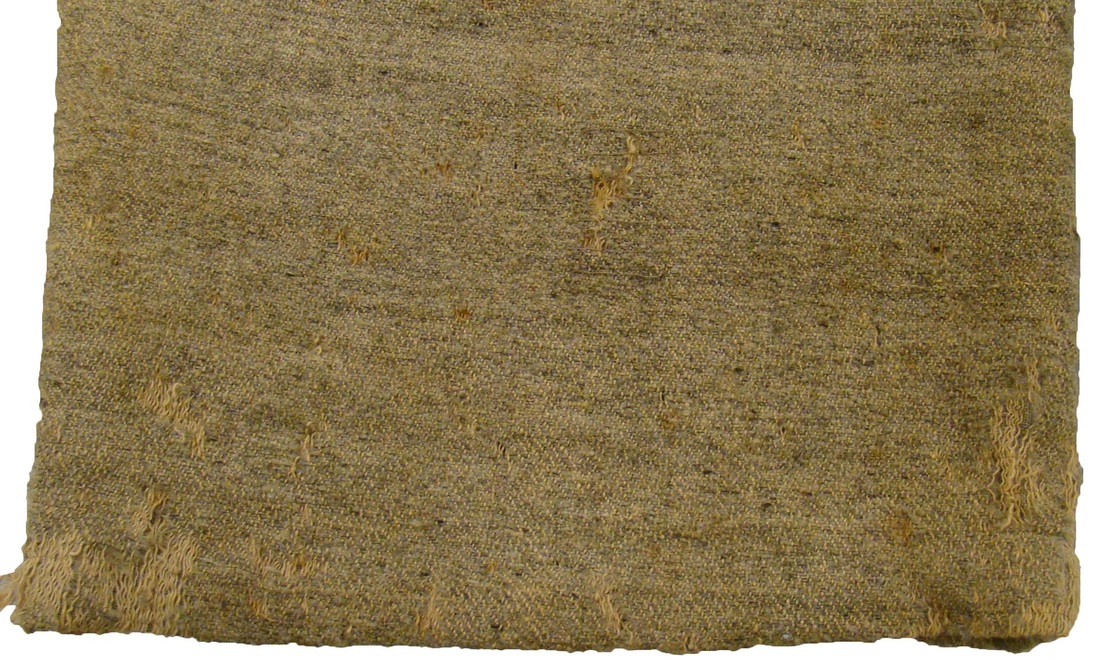

One pair of pants with very strong evidence identifying it to the Montgomery Depot is the Gettysburg National Park collection artifact with catalog number GETT 29077. It is the companion piece to the clearly identifiable Montgomery jacket, GETT 29076. As mentioned in the jacket’s description, the weave and color for both the jacket and pants match exactly. The weave has one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. The cotton warp yarn is a light tan color; the woolen weft yarn is a sheep's gray color; fabric color has a striped, or brindled appearance due to heterogeneous-colored fill yarn used intermittently in the weft. The trousers utilize the same wooden Allen buttons that the jacket has, except they are in the five-eighths inch pants size. The pants have side seam front pockets. The rear adjustment belt uses an Allen button and buttonhole in lieu of the usual pant buckle. The left belt piece had a button (now missing), and the right belt piece has a buttonhole. The fly closes with four Allen buttons (all intact): one at the waistband and the other three on the bottom fly piece. The pants are lined with same unbleached osnaburg as the jacket. The pants pieces have quarter-inch seam allowances. The waistband still retains its four, original Allen suspender buttons.[60] The similarities between the jacket and pants are so strong that it is safe to assume both pieces are the product of the same depot: Montgomery.

At least four pairs of pants have survived with provenance to the department: some accompanying Anderson or Montgomery jackets, and some alone. Taken as a whole, they do not conform to distinctive typologies. They do, however, share some traits that might reasonably associate them with one another or with the department’s quartermaster operations. In any case, assigning the trousers to one depot or the other, or linking them with each other is tenuous. This part of the study closely examines the surviving trousers’ provenance, tailoring, buttons, color, fabric and weave to surmise their origin.

One pair of pants with very strong evidence identifying it to the Montgomery Depot is the Gettysburg National Park collection artifact with catalog number GETT 29077. It is the companion piece to the clearly identifiable Montgomery jacket, GETT 29076. As mentioned in the jacket’s description, the weave and color for both the jacket and pants match exactly. The weave has one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. The cotton warp yarn is a light tan color; the woolen weft yarn is a sheep's gray color; fabric color has a striped, or brindled appearance due to heterogeneous-colored fill yarn used intermittently in the weft. The trousers utilize the same wooden Allen buttons that the jacket has, except they are in the five-eighths inch pants size. The pants have side seam front pockets. The rear adjustment belt uses an Allen button and buttonhole in lieu of the usual pant buckle. The left belt piece had a button (now missing), and the right belt piece has a buttonhole. The fly closes with four Allen buttons (all intact): one at the waistband and the other three on the bottom fly piece. The pants are lined with same unbleached osnaburg as the jacket. The pants pieces have quarter-inch seam allowances. The waistband still retains its four, original Allen suspender buttons.[60] The similarities between the jacket and pants are so strong that it is safe to assume both pieces are the product of the same depot: Montgomery.

17a. The most notable feature of the GETT 29077 pants is that they match the accompanying jacket, GETT 29076. The matching fabric, color, buttons and brindling all suggest that the jacket and pants were a from the same depot and came as a matching soldier's suit. The artifact in the 17-series of images is courtesy of the Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

17f. A close-up view of the rear seam notch and waistband construction is shown here. It appears that the waistband pieces were joined to the pants at the bottom seam with the undersides of the cloth facing outwards. They were then pressed upwards, the top seam allowances tucked into the waistband and the top seam whipstitched closed.

Another similar, complete Montgomery suit resides in the same collection: the jacket with catalog number GETT 29259, and the pants GETT 29260. As stated in the jacket description, the viewing conditions precluded definitive conclusions. The only feature visible on the pants was the grayish-tan colored, jeans fabric, itself tentative because of the fabric’s heavy nap. In any case, the color and type of fabric differ markedly from the jacket. Regrettably, this artifact yields no relevant information about its origins or similarities to other pants.[61]

Samuel Powell Cooper’s Montgomery jacket is accompanied by pants of a different fabric. Cooper presumably received the pants after the Tennessee Campaign, and by the time he was engaged in the Carolina Campaign. While his jacket came from the Montgomery Depot, his pants appear to have come from elsewhere. In fact, they are a perfect match with the Georgia Relief & Hospital Association pants worn by Hamilton Branch, 54th Georgia Infantry. Branch presumably received his pants in a Georgia hospital while sick and wounded in September 1864. It is plausible that Cooper could have gotten his pair of similar pants while the Army of Tennessee was assembling at Augusta, Georgia in late January 1865. In any case, they do not share characteristics that associate them with the department. The available images are too indistinct to draw definitive conclusions, but the weave appears to be a cassinet, and the overall color is tan. The pants have side seam opening pockets, and the fly closes with five buttons: one at the waistband and the other four on the bottom fly piece. Only one wooden button remains on the pants, at the fly, but it is too indistinct to identify. The rear of the pants have separate yoke pieces, and no adjustment belt (which may be missing). The rear waistband seam is closed all the way up, without leaving a notch. The pants are lined with unbleached osnaburg.[62] As mentioned before, they resemble the Georgia Relief & Hospital Association pants without the ink stamp, and would have been made in Georgia.

George Jacob Mook’s uniform includes a pair of pants. The pants neither match the fabric of Mook’s Montgomery jacket, nor do they share significant tailoring or fabric characteristics associated with Montgomery or Anderson’s depot trousers. As such, they do not appear to be depot-made. Mook’s diary further substantiates this conclusion. In an entry for May 17, 1865, while travelling home, Mook noted that a Miss Emily Garrison of Claiborne Parish, Louisiana had given him a pair of pants. In all likelihood, Mook’s surviving pants are those that Emily Garrison gave to him.

Mook’s pants are made of a natural white-colored, all-cotton, plain weave cloth fabric. By contrast, the Anderson depot fabric is a plain weave, woolen-cotton fabric that shows evidence of having a dyed weft, which suggests these pants were not made there. They have a five-button fly with one buttonhole at the waistband and four in the lower fly. The surviving buttons are natural white, four-hole bone pants buttons. The waistband has thread holes where the top fly button and six suspender buttons were placed. The pockets have “V” openings without buttonholes. The rear adjustment belt is fully intact with the tongue on the right and the iron, two-piece swivel buckle on the left. The rear leg panels have yokes added between the top and waistband. The yokes have vertical darts sewn in at the middle as if they had been cut too large for the waistband. The rear waistband seam is closed, rather than notched. The cuffs flare slightly with a “spring bottom” cut.[63]

Mook’s pants are made of a natural white-colored, all-cotton, plain weave cloth fabric. By contrast, the Anderson depot fabric is a plain weave, woolen-cotton fabric that shows evidence of having a dyed weft, which suggests these pants were not made there. They have a five-button fly with one buttonhole at the waistband and four in the lower fly. The surviving buttons are natural white, four-hole bone pants buttons. The waistband has thread holes where the top fly button and six suspender buttons were placed. The pockets have “V” openings without buttonholes. The rear adjustment belt is fully intact with the tongue on the right and the iron, two-piece swivel buckle on the left. The rear leg panels have yokes added between the top and waistband. The yokes have vertical darts sewn in at the middle as if they had been cut too large for the waistband. The rear waistband seam is closed, rather than notched. The cuffs flare slightly with a “spring bottom” cut.[63]

Two pairs of surviving pants with provenance to the department that are not associated with a one of the department’s depot jackets. These include those worn by C.W. Mitchell and Nathan Tisdale.

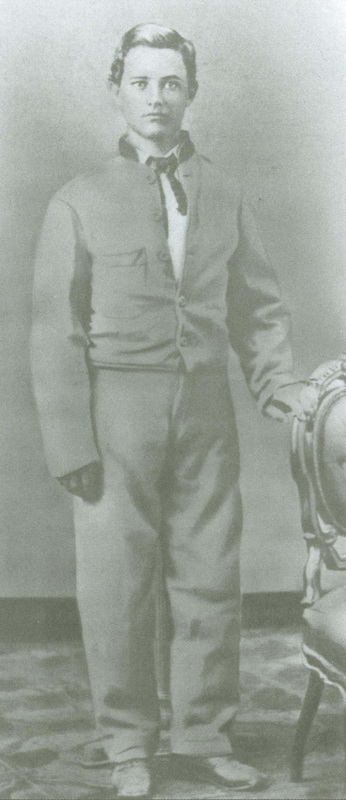

The first of these is similar to the GETT 29077 pants, and were worn by C.W. Mitchell, Company F, 7th Alabama Cavalry. Mitchell joined the army in 1863 at 16 years of age. His regiment fought in the Tennessee Campaign, where he was severely wounded in the left leg at Mount Pleasant, Tennessee. His next available record is his parole at Montgomery, dated May 9, 1865.[64] Mitchell’s trousers are the ones worn by him when he was wounded. He did not lose his left leg, but the hospital staff cut away the lower pant leg to treat his wound. He probably received these pants when the regiment was stationed in the Pollard area (close to Mobile) just prior to joining the Army of Tennessee the late summer of 1864, in which case, the pants were probably from one of the department’s depots. The pants’ weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. Both the woolen weft and the cotton warp yarns are a natural white color, the cotton being slightly lighter than the wool. The overall color is now a natural white with a very slight tannish cast, but when they were issued, they were apparently a cleaner natural white. All of the buttons are missing except for the waistband fly button, a five-eighths inch pants size, wooden Allen button. The pockets have “V” shaped openings. The rear adjustment belt has two buttonholes on the right piece and had one or two Allen buttons on the left piece that are now missing. The buttoning, rear adjustment belt closely matches that of the GETT 29077 pants. The fly has four buttonholes: one at the waistband and three in the fly piece. The pants are lined with unbleached osnaburg. The pants pieces have quarter-inch seam allowances.[65]

The first of these is similar to the GETT 29077 pants, and were worn by C.W. Mitchell, Company F, 7th Alabama Cavalry. Mitchell joined the army in 1863 at 16 years of age. His regiment fought in the Tennessee Campaign, where he was severely wounded in the left leg at Mount Pleasant, Tennessee. His next available record is his parole at Montgomery, dated May 9, 1865.[64] Mitchell’s trousers are the ones worn by him when he was wounded. He did not lose his left leg, but the hospital staff cut away the lower pant leg to treat his wound. He probably received these pants when the regiment was stationed in the Pollard area (close to Mobile) just prior to joining the Army of Tennessee the late summer of 1864, in which case, the pants were probably from one of the department’s depots. The pants’ weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. Both the woolen weft and the cotton warp yarns are a natural white color, the cotton being slightly lighter than the wool. The overall color is now a natural white with a very slight tannish cast, but when they were issued, they were apparently a cleaner natural white. All of the buttons are missing except for the waistband fly button, a five-eighths inch pants size, wooden Allen button. The pockets have “V” shaped openings. The rear adjustment belt has two buttonholes on the right piece and had one or two Allen buttons on the left piece that are now missing. The buttoning, rear adjustment belt closely matches that of the GETT 29077 pants. The fly has four buttonholes: one at the waistband and three in the fly piece. The pants are lined with unbleached osnaburg. The pants pieces have quarter-inch seam allowances.[65]

In 1902, the wife of former Private Nathan Tisdale, Company A, 30th Louisiana Infantry, donated her husband’s Confederate pants to Confederate Memorial Hall. According to her, Tisdale wore these pants when he has wounded at the Battle of Spanish Fort, 1865. Tisdale participated in the Tennessee Campaign of 1864, and remained in the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana afterwards. He was sent to the Quintard Confederate Hospital, Griffin, Georgia, after being wounded at Spanish Fort, and is listed on a roll of prisoners there in May 1865. He was officially surrendered at Citronelle, Alabama on May 4, 1865, and paroled at Meridian, Mississippi on May 10, but this may have been a formality since he was apparently in the hospital at Griffin, Georgia. Tisdale probably received his trousers while stationed at Mobile. The pants’ worn and dirty condition lend credence to his wife’s story that he wore them in battle during the spring of 1865.[66]

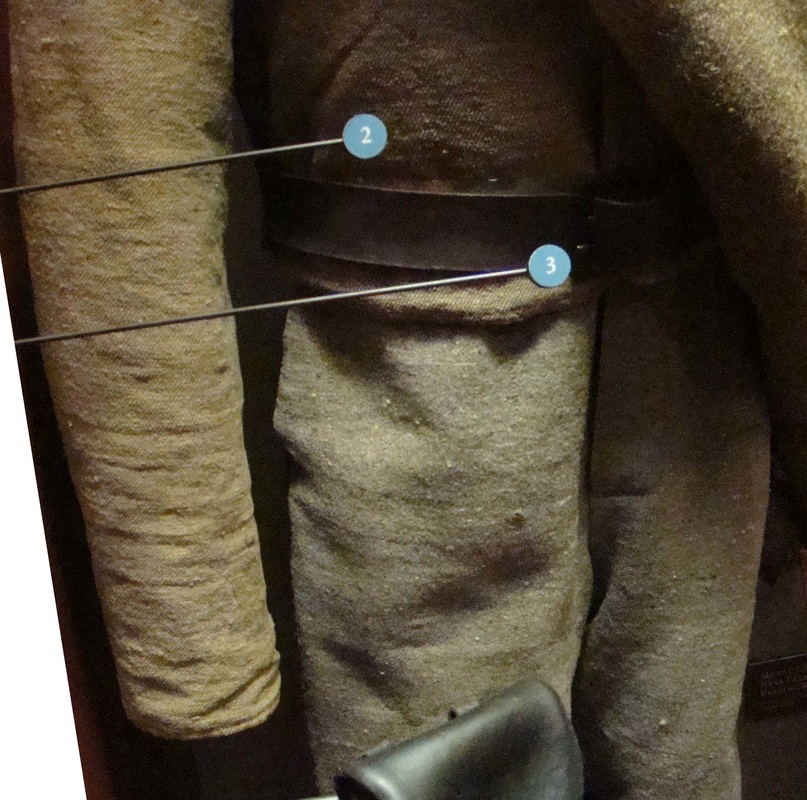

Tisdale’s trousers are remarkable in that the original, unsullied color of the fabric is visible on the protected surface under the right belt piece: the trousers are made of white woolen-cotton jeans cloth. The fabric weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarns, having a heavy, bleached white cotton warp, and a white woolen weft. Due to heavy soiling, the overall color of the jeans is now a grayish-beige in color, except where protected surfaces retain the original, natural white shade. All of the trousers’ linings and facings are of heavy, unbleached white cotton drill, not osnaburg. This is relevant because quartermasters in Montgomery and Selma used white cotton drills for this purpose, and this may be a clue that these are Montgomery Depot pants. The lining is likewise soiled, except for a few protected surfaces.

The trousers’ most salient tailoring feature is the front pocket construction. The two front pockets are top-opening in the manner of watch pockets. This pocket style matches that observed in a pair of Confederate pants in the Smithsonian Institution collection that is believed to have been made in a Mississippi factory. This style that was actually preferred by many soldiers. The openings have facing jeans welts along both to the inside and outside parts of the cotton drill pocket bags.

The fly is made with four buttonholes: three on the lower fly and one at the waistband. The only fly button remaining is a very rusty, stamped iron pants button at the waistband. The waistband retains its six, four-hole, natural white bone suspender buttons; two on each side in front and two in the rear.

The adjusting belt at the rear seam has the tongue portion on the left side, and the buckle portion on the right. The buckle is now missing but it left rust stains on both belt straps that show it was iron. The belt pieces consist of jeans fronts and cotton drill backs, and have identical tailoring with rounded ends. The end of the right belt piece is missing where it was folded over to hold the buckle.

Tisdale’s pants are lined as follows. The insides of the cuffs have cotton drill reinforcing bands sewn around the hemmed edge. The fly facings, waistband and reinforcing yoke pieces are also of cotton drill.[67]

Tisdale’s trousers are remarkable in that the original, unsullied color of the fabric is visible on the protected surface under the right belt piece: the trousers are made of white woolen-cotton jeans cloth. The fabric weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarns, having a heavy, bleached white cotton warp, and a white woolen weft. Due to heavy soiling, the overall color of the jeans is now a grayish-beige in color, except where protected surfaces retain the original, natural white shade. All of the trousers’ linings and facings are of heavy, unbleached white cotton drill, not osnaburg. This is relevant because quartermasters in Montgomery and Selma used white cotton drills for this purpose, and this may be a clue that these are Montgomery Depot pants. The lining is likewise soiled, except for a few protected surfaces.

The trousers’ most salient tailoring feature is the front pocket construction. The two front pockets are top-opening in the manner of watch pockets. This pocket style matches that observed in a pair of Confederate pants in the Smithsonian Institution collection that is believed to have been made in a Mississippi factory. This style that was actually preferred by many soldiers. The openings have facing jeans welts along both to the inside and outside parts of the cotton drill pocket bags.

The fly is made with four buttonholes: three on the lower fly and one at the waistband. The only fly button remaining is a very rusty, stamped iron pants button at the waistband. The waistband retains its six, four-hole, natural white bone suspender buttons; two on each side in front and two in the rear.

The adjusting belt at the rear seam has the tongue portion on the left side, and the buckle portion on the right. The buckle is now missing but it left rust stains on both belt straps that show it was iron. The belt pieces consist of jeans fronts and cotton drill backs, and have identical tailoring with rounded ends. The end of the right belt piece is missing where it was folded over to hold the buckle.

Tisdale’s pants are lined as follows. The insides of the cuffs have cotton drill reinforcing bands sewn around the hemmed edge. The fly facings, waistband and reinforcing yoke pieces are also of cotton drill.[67]

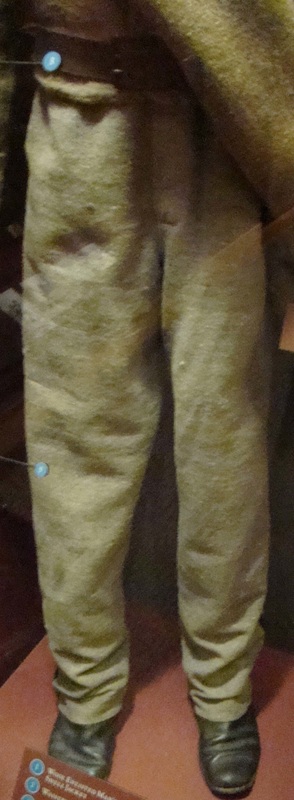

23a. A full frontal view of Tisdale's pants shows how dirty they are. The right cuff has been folded upwards, making the leg appear shorter than the left. The pants appear to be a tannish-gray color, but this is actually discoloration brought about by heavy soiling. When newly manufactured, the pants were a natural white color. The artifact in the 23-series of images is courtesy of Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana.

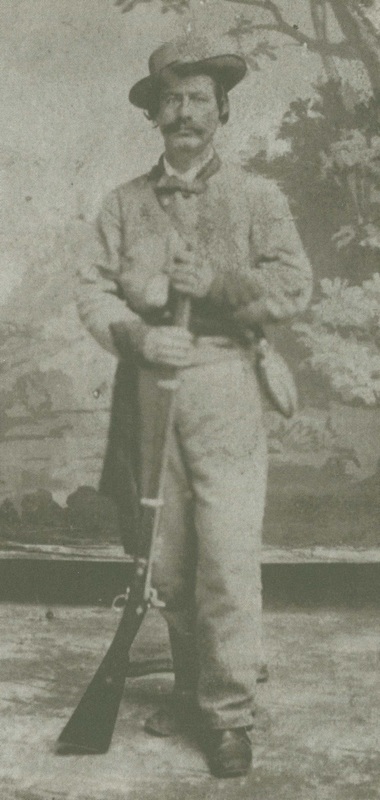

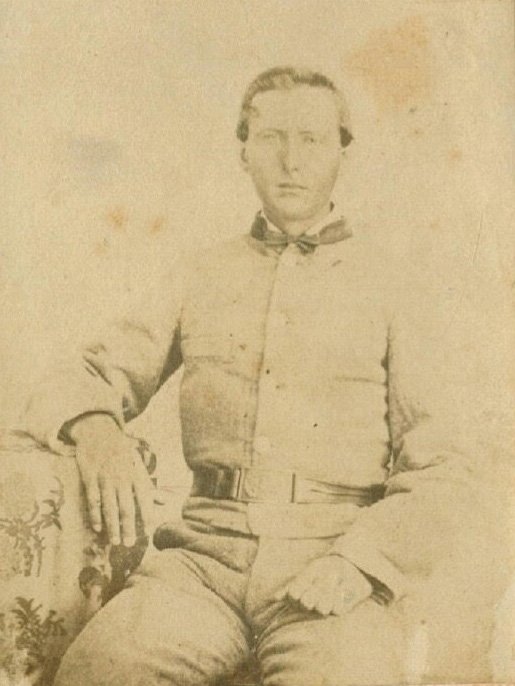

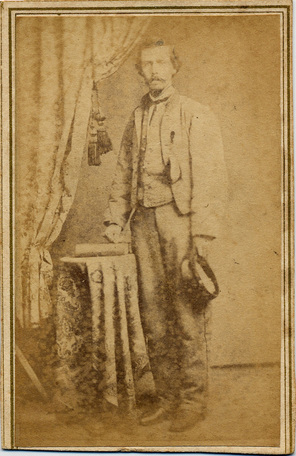

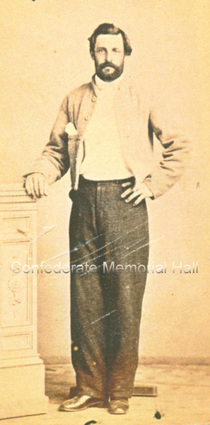

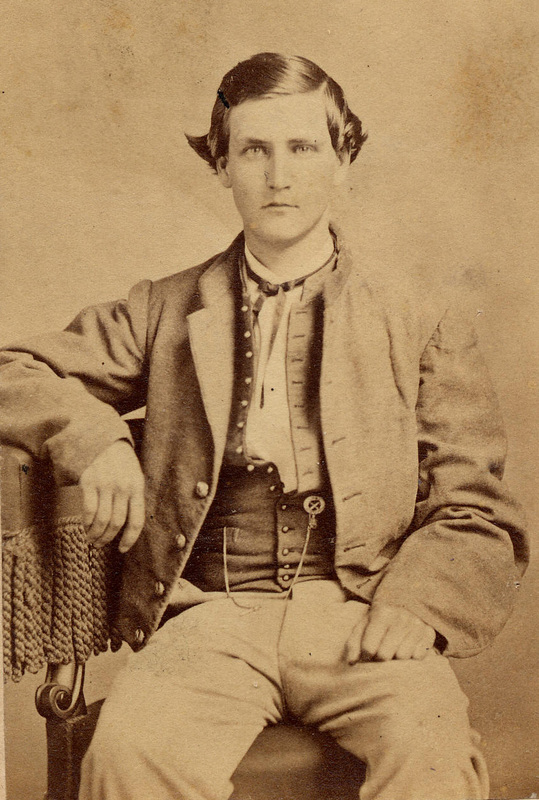

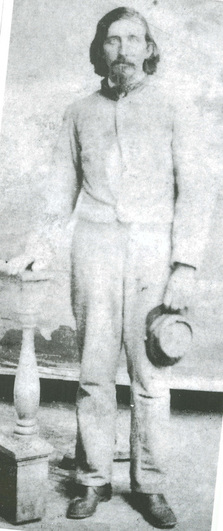

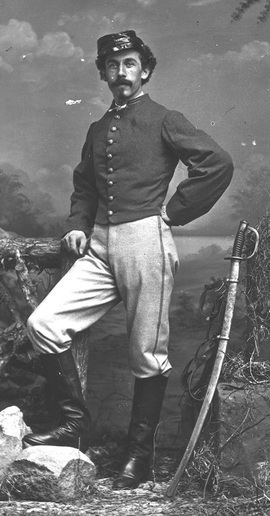

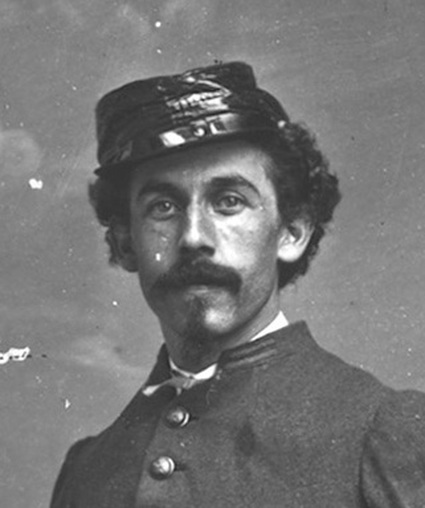

Finally, there are numerous portraits depicting soldiers wearing Anderson or Montgomery jackets with matching pants. These are somewhat inconclusive due to a lack details other than matching fabric and color. Other portraits with provenance to the department provide substantiating evidence for the frequent use of white trousers by soldiers there. Four images in particular are noteworthy. These include an unidentified “Louisiana Zouave” with white pants and a cadet gray jacket; Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron wearing white pants with his officer frock coat; and, Private Benjamin Bridge, Jr., and Samuel Brooks Newman, Jr., both with a tailored jackets and white pants. All four of these images were made in Mobile or New Orleans in May 1865, and the men served in Mobile at the close of the war.[68] Another images depicts a Washington Artilleryman, James Clarke, wearing what may have been cadet gray trousers.[69] Clarke was present with his command at the surrender at Citronelle, Alabama, May 4, 1865, and probably had the pants made up from cadet gray cloth issued by the Confederate quartermaster.

Due to the variations in the surviving examples, only a few general conclusions can be drawn about the Montgomery and Anderson Depot pants. Regarding color, both depots apparently made trousers in both the matching color of the jackets and in undyed, natural white. The GETT 29077 pants are such a close match to their accompanying jacket, that it seems likely that they are a Montgomery Depot product. Mitchell’s natural white pants conform to the GETT 29077 pants having the same button-style adjustment belt and the same jeans weave. The Tisdale trousers match the Montgomery jacket fabric in the jeans weave, and are white in color, but their tailoring is different from the GETT 29077 and Mitchell pants. The characteristics of the GETT 29260 pants are inconclusive. I would assign the GETT 29077 and Mitchell pants to the Montgomery Depot. I also believe that the Tisdale pants were made in the department, most likely by a small factory that supplied one of the two depots, using a pattern unique to that factory.

Only a few examples of caps survive with provenance to the department, including two originals and some portraits. This is not surprising since the Confederate quartermaster was probably issuing more hats than caps by 1864, and most Confederate soldiers preferred hats to caps. Nonetheless, many caps were issued and some soldiers, especially artillerymen, preferred them. Although the infantry wore far more hats than caps, it is interesting to note that over the course of the war, from October 1861 through April 1864, the 6th Mississippi Infantry Regiment was issued 937 caps, and 388 hats, or caps at a ratio of nearly three-to-one. All but 170 caps were issued from various depots in Mississippi and Alabama, the last 179 caps in April 1864 being drawn at Demopolis.[70] Even cavalrymen occasionally donned caps late in the war, as noted by E.N. Gilpin, 3rd Iowa Cavalry. Gilpin recorded in his journal on April 10, 1865 in Church Hill, Alabama, of the Confederate cavalry, “They were gallant fellows, as they rode at a gallop, their long hair blowing behind their little Secesh caps. As they leaped the fences, it was a goodly sight.”[71] With this in mind, we can consider the few depot caps attributed to the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana as being representative of its production.

There are two caps with provenance to the department: the Arthur A. Crews and the Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron caps. Two CDVs taken in May 1865 in Mobile and New Orleans show soldiers holding caps. All of these caps have the quintessential chasseur tailoring that is the hall mark of the Southern cap. The chasseur cap’s features include the countersunk crown into the sides; the separate band piece, a deep scallop in the visor that kept it flat, and the relatively low height as compared to the Northern forage cap. All of these described herein are made of domestically produced basic cloth, and the linings are of unbleached white osnaburg.

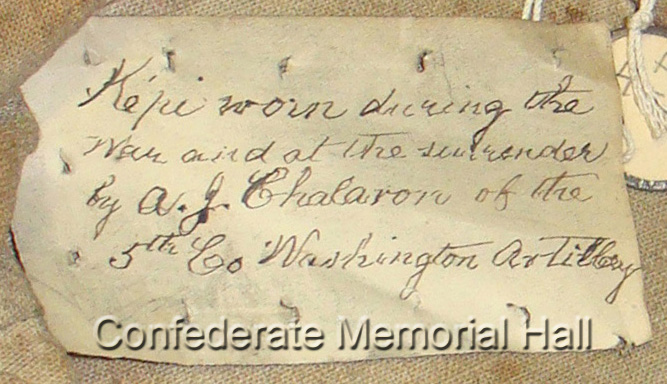

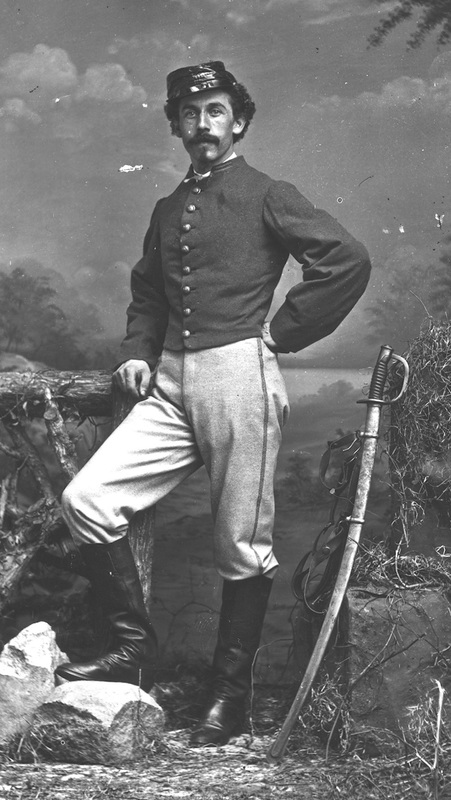

The first cap was worn by Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron, 5th Company, Louisiana Washington Artillery. This company fought in the Army of Tennessee, and after the Tennessee Campaign of 1864, it was assigned Mobile where it served to the end of the war. Chalaron was present at the company’s last battle at Spanish Fort, and when the army of Mobile surrendered in May 1865. Chalaron probably received his cap between the time his company returned from the Tennessee Campaign in December and when the army disbanded in May. Despite him being an officer, he drew an enlisted depot cap, as many officers did in the Western theater, and he added a band of eighth-inch gold lace to the non-functional chinstrap to denote his rank.[72] Chalaron’s cap is accompanied by an enameled rain cover that he may have acquired privately.

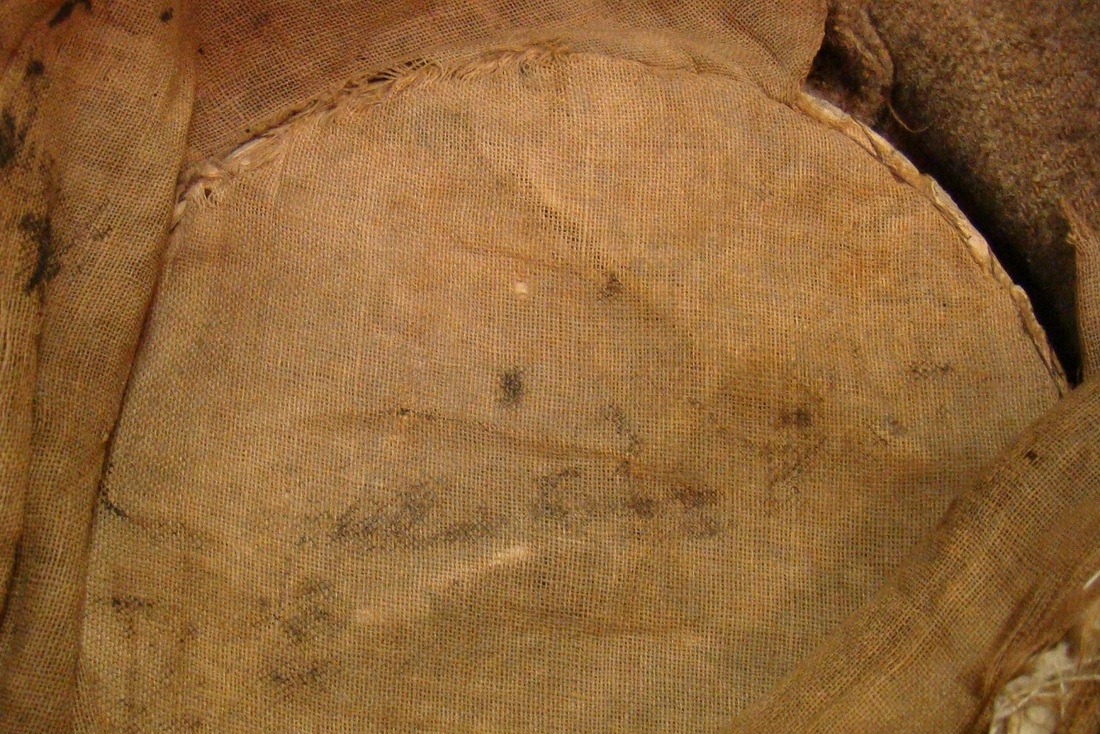

The basic fabric weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarns, and a cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarns. This matches the Montgomery jacket weave which strengthens the evidence of it having been made at the Montgomery Depot. The woolen fill yarn is an oatmeal or undyed, natural white color; the cotton warp is a yellowish, golden brown color. The woolen fill yarn was probably originally dyed gray shade, but it has since faded. The yellowish-beige cotton warp yarns blending with the oatmeal colored woolen fill yarns give the fabric the overall effect of being tan or beige colored. The inner lining is an unbleached, natural white, cotton osnaburg.

Chalaron’s cap has some remarkable characteristics. Instead of a buckram stiffener in the band, this cap has a heavy cardboard stiffener (of two pieces) that was apparently glued in place originally. The rear seam is stiffened with a piece of bowed river cane that extends from the fold in the crown all the way to the bottom of the band. The cardboard visor is covered with enameled cotton drilling, and has a raw edged welt of enameled osnaburg binding the outer edge. The visor was whipstitched to the front of the cap, and the welt was machine-stitched around the outer edge of the visor at ten stitches per inch. The rather wide (three-quarters of an inch), one-piece, non-functional, raw-cut chinstrap is cut from enameled osnaburg. The bottom edge of the chinstrap overlaps the seam of the visor, which may account for its unusual width. As alluded to previously, the chinstrap has a strand of one-eighth inch gold lace tacked along the center of its entire length. The original chinstrap buttons are missing.

The enameled osnaburg sweatband is whipstitched with close stitches to base of the cap and with the raw edge exposed. The wider stitching now present is restoration stitching from the 1970s. The top of the sweatband is not stitched to the lining.

The rest of the construction is typical: the outer basic cloth pieces consist of two side pieces, a separate one-piece band, and a countersunk crown piece. The inner lining consists of two side pieces and the crown, albeit the left side lining piece has been pieced together with two pieces of scrap. The crown appears to be of pasteboard. The height of the cap in front is three inches.

The enameled rain cover fits over the cap and is made with two side pieces and a crown piece.

Only a few examples of caps survive with provenance to the department, including two originals and some portraits. This is not surprising since the Confederate quartermaster was probably issuing more hats than caps by 1864, and most Confederate soldiers preferred hats to caps. Nonetheless, many caps were issued and some soldiers, especially artillerymen, preferred them. Although the infantry wore far more hats than caps, it is interesting to note that over the course of the war, from October 1861 through April 1864, the 6th Mississippi Infantry Regiment was issued 937 caps, and 388 hats, or caps at a ratio of nearly three-to-one. All but 170 caps were issued from various depots in Mississippi and Alabama, the last 179 caps in April 1864 being drawn at Demopolis.[70] Even cavalrymen occasionally donned caps late in the war, as noted by E.N. Gilpin, 3rd Iowa Cavalry. Gilpin recorded in his journal on April 10, 1865 in Church Hill, Alabama, of the Confederate cavalry, “They were gallant fellows, as they rode at a gallop, their long hair blowing behind their little Secesh caps. As they leaped the fences, it was a goodly sight.”[71] With this in mind, we can consider the few depot caps attributed to the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana as being representative of its production.

There are two caps with provenance to the department: the Arthur A. Crews and the Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron caps. Two CDVs taken in May 1865 in Mobile and New Orleans show soldiers holding caps. All of these caps have the quintessential chasseur tailoring that is the hall mark of the Southern cap. The chasseur cap’s features include the countersunk crown into the sides; the separate band piece, a deep scallop in the visor that kept it flat, and the relatively low height as compared to the Northern forage cap. All of these described herein are made of domestically produced basic cloth, and the linings are of unbleached white osnaburg.

The first cap was worn by Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron, 5th Company, Louisiana Washington Artillery. This company fought in the Army of Tennessee, and after the Tennessee Campaign of 1864, it was assigned Mobile where it served to the end of the war. Chalaron was present at the company’s last battle at Spanish Fort, and when the army of Mobile surrendered in May 1865. Chalaron probably received his cap between the time his company returned from the Tennessee Campaign in December and when the army disbanded in May. Despite him being an officer, he drew an enlisted depot cap, as many officers did in the Western theater, and he added a band of eighth-inch gold lace to the non-functional chinstrap to denote his rank.[72] Chalaron’s cap is accompanied by an enameled rain cover that he may have acquired privately.

The basic fabric weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarns, and a cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarns. This matches the Montgomery jacket weave which strengthens the evidence of it having been made at the Montgomery Depot. The woolen fill yarn is an oatmeal or undyed, natural white color; the cotton warp is a yellowish, golden brown color. The woolen fill yarn was probably originally dyed gray shade, but it has since faded. The yellowish-beige cotton warp yarns blending with the oatmeal colored woolen fill yarns give the fabric the overall effect of being tan or beige colored. The inner lining is an unbleached, natural white, cotton osnaburg.

Chalaron’s cap has some remarkable characteristics. Instead of a buckram stiffener in the band, this cap has a heavy cardboard stiffener (of two pieces) that was apparently glued in place originally. The rear seam is stiffened with a piece of bowed river cane that extends from the fold in the crown all the way to the bottom of the band. The cardboard visor is covered with enameled cotton drilling, and has a raw edged welt of enameled osnaburg binding the outer edge. The visor was whipstitched to the front of the cap, and the welt was machine-stitched around the outer edge of the visor at ten stitches per inch. The rather wide (three-quarters of an inch), one-piece, non-functional, raw-cut chinstrap is cut from enameled osnaburg. The bottom edge of the chinstrap overlaps the seam of the visor, which may account for its unusual width. As alluded to previously, the chinstrap has a strand of one-eighth inch gold lace tacked along the center of its entire length. The original chinstrap buttons are missing.

The enameled osnaburg sweatband is whipstitched with close stitches to base of the cap and with the raw edge exposed. The wider stitching now present is restoration stitching from the 1970s. The top of the sweatband is not stitched to the lining.

The rest of the construction is typical: the outer basic cloth pieces consist of two side pieces, a separate one-piece band, and a countersunk crown piece. The inner lining consists of two side pieces and the crown, albeit the left side lining piece has been pieced together with two pieces of scrap. The crown appears to be of pasteboard. The height of the cap in front is three inches.

The enameled rain cover fits over the cap and is made with two side pieces and a crown piece.

25a. Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron's enlisted cap is one of the few surviving originals of the Lower South with impeccable provenance. The quartermaster would have issued this type of cap to the soldiers in Alabama and Mississippi. The artifact in the 25-series of images is courtesy of Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana.

25g. A view of the left rear shows one of the cap's unique features: the cane stiffener placed along the rear side and band seams from the crown down to the bottom edge of the band. Further, the band itself is stiffened with sturdy pasteboard, that was originally glued in place, rather than the usual buckram. The black threads showing at the base of the stiffener were added by a conservator ca. 2000.

25q. The sweatband was sewn into the cap with a raw edge. It was whipstitched in place along the bottom edge of the band with a double, black thread. The top edge of the sweatband was not sewn to the lining, except for the back seam, where the top was secured to the lining with a couple of stitches (now missing).

The next cap was worn by Arthur A. Crews of the 29th Alabama Infantry. The cap’s provenance to the department is a bit more tenuous than Chalaron’s. Crews accompanied the Army of Tennessee on its retreat from the Tennessee Campaign, where it came to rest in Northern Mississippi. Some weeks later, his regiment deployed to the Carolinas with that portion of the Army of Tennessee that was sent east. Crews ended the war at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865.[73] He may have gotten the cap during his short interlude in Mississippi. In any case, the cap’s cloth matches the linsey weave that is well documented to the Montgomery clothing factories. The weave is one woolen yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over two woolen yarns. This woolen weft yarn is oatmeal, natural white colored; the cotton warp yarn is light, golden tan colored. The overall effect of the cloth color is a light, dusty tan. The nap is still intact in some patches, and appears to have faded from steel gray. The non-functional, one-piece chinstrap is intact, albeit faded. It is a woven tulle band, now black and brown, but probably originally black. The buttons are also intact: cloth covered, two-piece metal. The visor is made from leather. Both the glazing and paint are worn away, leaving it a medium-dark brown color. The visor is unusual in that the front width is only one-and-a-half inches, whereas most Confederate visors are about two inches wide. Its shape is also quite distinct, being somewhat more curved along the outer front edge than the typical Confederate visor. The sweatband (now missing) was made from enameled cloth (evident by the paint stains on the plain weave cotton lining, where it once was). The lining material does not appear to be osnaburg, but another cotton tabby weave. The tailoring follows the quintessential chasseur pattern having a one-piece band, low sides and countersunk crown. The front height of the cap is three inches.[74] The fabric weave matches that observed in the Thomas Taylor jacket.

26a. Arthur A. Crews's cap is another scarce example of a surviving enlisted cap from the Western Confederacy with solid provenance. This view highlights the peculiar shaped visor which is narrow in width with inward tapering sides. The artifact in the 26-series of images is courtesy of the Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia.

As previously described in the section on Anderson jackets, an unidentified soldier holds a cap in a CDV from “Ben Oppenheimer, 55-66 Dauphin Street, Mobile,” taken in May 1865.[75] The cap has brass buttons, and appears to have a dark blue band. The “blue band” may be a shadow rather than a contrasting color. Interestingly, the visor shape is similar to that observed in the Crews cap visor.

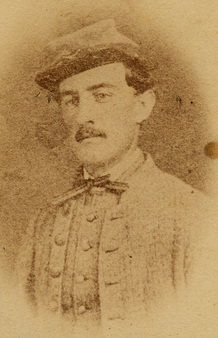

Considering Robert W. Frazer’s CDV, his cap is especially interesting because it shows both the interior and the colored band. The cap’s white lining appears to be an unbleached osnaburg, and its black sweatband is probably enameled cloth. A brass button secures one side of the chinstrap that is visible. The cap clearly has a colored band, darker than the basic cloth, but of an indiscernible color (as is the collar facing). The band and collar could be either dark blue or red, but consider Frazer’s artillery affiliation, the band was most likely red.[76]

Similar to the previous two images discussed, a CDV of William W. Sewell, 5th Company, Washington Artillery, shows him wearing a cap with what appears to be a red band and gray sides and crown. A small brass, crossed cannon badge is attached to the red band. The may represent a cap from the department, since the image appears to have been made soon after the war by Anderson of New Orleans. However, Sewell’s service records state that he was killed in action at Dallas, Georgia, May 28, 1864, in which case the cap probably came from the Columbus, Georgia Depot.[77]

Two images depict enamel caps: that of the unidentified “Louisiana Zouave” and Felix Arroyo. These do not appear to be covers, but actual caps made from enamel cloth, complete with the countersunk crown. There is no evidence to suggest that these enamel caps were issued by the Confederate quartermaster. Perhaps they were private purchase items.[78]

Despite a meager sampling of caps from the department, a few conclusions can be drawn. The quintessential, solid colored chasseur cap with an enameled cloth visor, as worn by Chalaron, must have been available in some numbers. Judging from its fabric that matches that observed in the Montgomery jackets, perhaps it was made at the Montgomery Depot, too. The Crews chasseur-style cap is readily identifiable by its distinctively shaped leather visor, with a pronounced curve along its outer edge and a narrow width. Its fabric matches the linsey weave observed in the Taylor jacket: a possible link to Montgomery, as well. An unidentified soldier, from a CDV taken by Ben Oppenheimer of Mobile, holds a cap that resembles Crews’s cap, especially its distinctive visor shape. The Crews cap may represent another variant manufactured in the department. Finally, Frazer’s and Sewell’s portraits show caps with colored bands, which may represent a third variant of cap issued in the department.

Considering Robert W. Frazer’s CDV, his cap is especially interesting because it shows both the interior and the colored band. The cap’s white lining appears to be an unbleached osnaburg, and its black sweatband is probably enameled cloth. A brass button secures one side of the chinstrap that is visible. The cap clearly has a colored band, darker than the basic cloth, but of an indiscernible color (as is the collar facing). The band and collar could be either dark blue or red, but consider Frazer’s artillery affiliation, the band was most likely red.[76]

Similar to the previous two images discussed, a CDV of William W. Sewell, 5th Company, Washington Artillery, shows him wearing a cap with what appears to be a red band and gray sides and crown. A small brass, crossed cannon badge is attached to the red band. The may represent a cap from the department, since the image appears to have been made soon after the war by Anderson of New Orleans. However, Sewell’s service records state that he was killed in action at Dallas, Georgia, May 28, 1864, in which case the cap probably came from the Columbus, Georgia Depot.[77]

Two images depict enamel caps: that of the unidentified “Louisiana Zouave” and Felix Arroyo. These do not appear to be covers, but actual caps made from enamel cloth, complete with the countersunk crown. There is no evidence to suggest that these enamel caps were issued by the Confederate quartermaster. Perhaps they were private purchase items.[78]

Despite a meager sampling of caps from the department, a few conclusions can be drawn. The quintessential, solid colored chasseur cap with an enameled cloth visor, as worn by Chalaron, must have been available in some numbers. Judging from its fabric that matches that observed in the Montgomery jackets, perhaps it was made at the Montgomery Depot, too. The Crews chasseur-style cap is readily identifiable by its distinctively shaped leather visor, with a pronounced curve along its outer edge and a narrow width. Its fabric matches the linsey weave observed in the Taylor jacket: a possible link to Montgomery, as well. An unidentified soldier, from a CDV taken by Ben Oppenheimer of Mobile, holds a cap that resembles Crews’s cap, especially its distinctive visor shape. The Crews cap may represent another variant manufactured in the department. Finally, Frazer’s and Sewell’s portraits show caps with colored bands, which may represent a third variant of cap issued in the department.

At least one hat with department provenance survives that appears to have been made for the Confederate army: this being Silas Buck’s hat (accompanying his Anderson jacket). Buck’s hat may be the only surviving depot-issue hat from the department. It has several salient features that suggest an army hat. The cheap wool felt is what was used in domestically made enlisted hats for the quartermaster department. The wool itself is of simplest manufacture, being undyed and unbleached, of a tannish, light brown color with a mottled appearance and some dark flecks throughout. The hat’s accessories are all made of raw edged, enameled cloth: a common substitute for leather and grosgrain used in Confederate army clothing. The crown was originally formed into a cylindrical, “pill box” shape, and although it is a bit misshapen, it retains enough of its original shape to identify its form. The welt edging, outer band and sweatband are all made from enameled cloth. The dimensions are as follows: the brim is approximately three inches wide all around; the crown three inches high; the raw edged outer band roughly 5/8 of an inch wide; the raw cut welt 7/8 of an inch wide; the raw edged sweatband one and a quarter inches wide; and, the top of the crown seven and a quarter inches from front to rear, and six inches from side to side. The interior circumference at the bottom edge is twenty-four inches. One side of the brim is affixed to the crown with a copper rivet. The provenance is tied to Silas Buck, whose service is previously recounted in the description of his Anderson jacket, and who probably received the hat along with his other quartermaster issue clothing.[79]

28a. Silas Buck's hat appears to have been made for the Confederate army and general issue. It is made of simple wool felt with enamel cloth fittings that have been substituted for components typically used in making hats. The artifact in the 28-series of images is courtesy of a private collection viewed by the author in July 2015.

Finally, no study of the department’s uniforms would be complete without including the cadet gray jackets and trousers worn by the Confederate troops in Mobile. Two of these uniforms survive, and both have the appearance of having been tailor- rather than depot-made. Both uniforms were worn by soldiers in the same command: Fenner’s Battery, Louisiana Light Artillery. They include the jacket and trousers of Rene Henry Brunet, and the jacket of John William Noyes.[80]

While the depot operations at Montgomery and Columbus manufactured adequate amounts of clothing for the troops of the department, some had uniforms made up from cadet gray cloth furnished by the Confederate government. Confederate quartermaster authorities in Alabama purchased a quantity of imported cadet gray cloth from the Alabama State Quartermaster, in both coarse enlisted grade, and fine officer grade, and in turn sold this to troops in the Mobile area, in late 1865 to early 1865. Since the troops received the cloth, in lieu of ready-made clothing, they had to have local tailors make it into a uniform. The two surviving enlisted uniforms made from this cloth reflect the final variant of enlisted clothing worn by Confederate soldiers in the department.

Fenner’s Battery had served in the Army of Tennessee during the Atlanta and Tennessee campaigns. Due to severe losses in the Army of Tennessee’s artillery corps following the Tennessee campaign, the remaining guns, horses, and artillery equipment were taken from Fenner’s Battery and redistributed to other light batteries. Fenner’s cannoneers were re-assigned in January 1865 as heavy artillery in the Mobile City defenses. The command remained in Mobile until the city fell in April, where upon, the men marched to Meridian, where they were paroled about a month later. Sometime, shortly after arriving in Mobile, Brunet and Noyes had their cadet gray uniforms made.

Rene Henry Brunet’s jacket and pants are made of coarse, enlisted grade kersey which is a lighter cadet gray than typically encountered with Confederate clothing. The plain jacket has a seven button front, with five of its Louisiana pelican buttons intact. The outer jacket shell has one-piece sleeves and a six-piece body. The medium-brown cotton body lining consists of a single back piece and two wide side pieces. The side pieces join directly to the two wide kersey facing lapels, thus eliminating the need for intervening front lining pieces. The interior breasts each have an inset pocket of unbleached osnaburg with kersey welts. The one-piece sleeve linings are also made from unbleached osnaburg. Interestingly, the lining has wedges filling out gaps, suggesting that the tailor had to re-cut Brunet’s jacket, or did not have large enough pieces of material to cut the lining components as single pieces.

Brunet’s pants are also made plainly without any facings. Their most salient feature is the integral, versus a separate, waistband, with the leg pieces are cut high enough to incorporate this feature. The pants linings and pockets are unbleached osnaburgs, and interlinings are made from sky-blue, woolen-cotton jeans. The pants have side seam opening pockets, an inset watch pocket in the right waist band, and an adjustment belt at the rear seam that fastens with a brass, swivel-style buckle (on the left side). The fly closes with five, black horn, four-hole buttons, with the top button concealed under the fly. The interior front of each cuff is lined with sky-blue jeans. The well-worn trouser seat has been patched on the inside with steel gray wool cloth which suggests that Brunet wore his trousers for several months before the war ended. Furthermore, the waist was taken in, apparently by Brunet himself, by cutting vertically through rear panels at the waist seam, and sewing darts in place without finishing the edges.[81]

While the depot operations at Montgomery and Columbus manufactured adequate amounts of clothing for the troops of the department, some had uniforms made up from cadet gray cloth furnished by the Confederate government. Confederate quartermaster authorities in Alabama purchased a quantity of imported cadet gray cloth from the Alabama State Quartermaster, in both coarse enlisted grade, and fine officer grade, and in turn sold this to troops in the Mobile area, in late 1865 to early 1865. Since the troops received the cloth, in lieu of ready-made clothing, they had to have local tailors make it into a uniform. The two surviving enlisted uniforms made from this cloth reflect the final variant of enlisted clothing worn by Confederate soldiers in the department.

Fenner’s Battery had served in the Army of Tennessee during the Atlanta and Tennessee campaigns. Due to severe losses in the Army of Tennessee’s artillery corps following the Tennessee campaign, the remaining guns, horses, and artillery equipment were taken from Fenner’s Battery and redistributed to other light batteries. Fenner’s cannoneers were re-assigned in January 1865 as heavy artillery in the Mobile City defenses. The command remained in Mobile until the city fell in April, where upon, the men marched to Meridian, where they were paroled about a month later. Sometime, shortly after arriving in Mobile, Brunet and Noyes had their cadet gray uniforms made.

Rene Henry Brunet’s jacket and pants are made of coarse, enlisted grade kersey which is a lighter cadet gray than typically encountered with Confederate clothing. The plain jacket has a seven button front, with five of its Louisiana pelican buttons intact. The outer jacket shell has one-piece sleeves and a six-piece body. The medium-brown cotton body lining consists of a single back piece and two wide side pieces. The side pieces join directly to the two wide kersey facing lapels, thus eliminating the need for intervening front lining pieces. The interior breasts each have an inset pocket of unbleached osnaburg with kersey welts. The one-piece sleeve linings are also made from unbleached osnaburg. Interestingly, the lining has wedges filling out gaps, suggesting that the tailor had to re-cut Brunet’s jacket, or did not have large enough pieces of material to cut the lining components as single pieces.

Brunet’s pants are also made plainly without any facings. Their most salient feature is the integral, versus a separate, waistband, with the leg pieces are cut high enough to incorporate this feature. The pants linings and pockets are unbleached osnaburgs, and interlinings are made from sky-blue, woolen-cotton jeans. The pants have side seam opening pockets, an inset watch pocket in the right waist band, and an adjustment belt at the rear seam that fastens with a brass, swivel-style buckle (on the left side). The fly closes with five, black horn, four-hole buttons, with the top button concealed under the fly. The interior front of each cuff is lined with sky-blue jeans. The well-worn trouser seat has been patched on the inside with steel gray wool cloth which suggests that Brunet wore his trousers for several months before the war ended. Furthermore, the waist was taken in, apparently by Brunet himself, by cutting vertically through rear panels at the waist seam, and sewing darts in place without finishing the edges.[81]

While Brunet opted for a simple uniform, John William Noyes had a deluxe version made for himself. His jacket has red facings and the cadet gray cloth is a darker shade. The jacket consists of a six-piece body with two-piece sleeves. The collar is two-piece, both outside and inside. The jacket has nine buttonholes, but the buttons are missing. The lining follows the same construction as the outer fabric with the addition of facing lapels on the front lining pieces. The lining has one inset pocket in the left breast. The lining material in the body, to include the breast pocket, is light brown, plain weave cotton, and the sleeve linings are unbleached osnaburg. The jacket has no topstitching.

Similar to the Brunet jacket, Noyes’s jacket has wedges added to the body, suggesting that the tailor may have re-sized the jacket for Noyes. These are inserted between the front and side pieces at the bottom of the jacket, on either side, both in the outer fabric and the lining. The cadet gray, outer fabric wedges have a distinctly grayer hue than the rest of the kersey. The tailor also used some thrift in cutting the fabric, having pieced the facing lapels from smaller scraps of cloth.

The jacket has narrow, one-half inch belt loops attached to the bottom edges of the front pieces next to the adjoining wedges. The three and one-eighth inch long loops are sewn to the jacket at their tops.

The facings are made from plain weave, red woolen fabric. The seams of the one-piece, pointed cuffs align with the rear sleeve seams. The red collar facing has a buckram interlining. The collar is one and one-quarter inches high at the rear seam, and the front edges are about one-eighth of an inch lower than the rear height. The edges of the collar are pointed.[82]

Similar to the Brunet jacket, Noyes’s jacket has wedges added to the body, suggesting that the tailor may have re-sized the jacket for Noyes. These are inserted between the front and side pieces at the bottom of the jacket, on either side, both in the outer fabric and the lining. The cadet gray, outer fabric wedges have a distinctly grayer hue than the rest of the kersey. The tailor also used some thrift in cutting the fabric, having pieced the facing lapels from smaller scraps of cloth.

The jacket has narrow, one-half inch belt loops attached to the bottom edges of the front pieces next to the adjoining wedges. The three and one-eighth inch long loops are sewn to the jacket at their tops.

The facings are made from plain weave, red woolen fabric. The seams of the one-piece, pointed cuffs align with the rear sleeve seams. The red collar facing has a buckram interlining. The collar is one and one-quarter inches high at the rear seam, and the front edges are about one-eighth of an inch lower than the rear height. The edges of the collar are pointed.[82]

31a. John William Noyes went to a little more expense at the tailor shop when having his cloth made into a uniform. The cloth itself is an officer grade quality. The sleeves are two-piece, there are nine buttonholes along the front, and the jacket has red facings. The artifact in the 31-series of images is courtesy of Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana.

31e. The rear of Noyes's jacket shows an interesting feature in the tailoring. Between the front and side pieces, gussets have been added to increase the girth. The gussets contrast in shade to the rest of the basic cloth, but are nonetheless a fine, officer grade cloth. One might speculate that when Noyes went to fetch the jacket at the tailor shop, he found that it was cut to spare, and the tailor had to let out the waist line with the contrasting gussets.

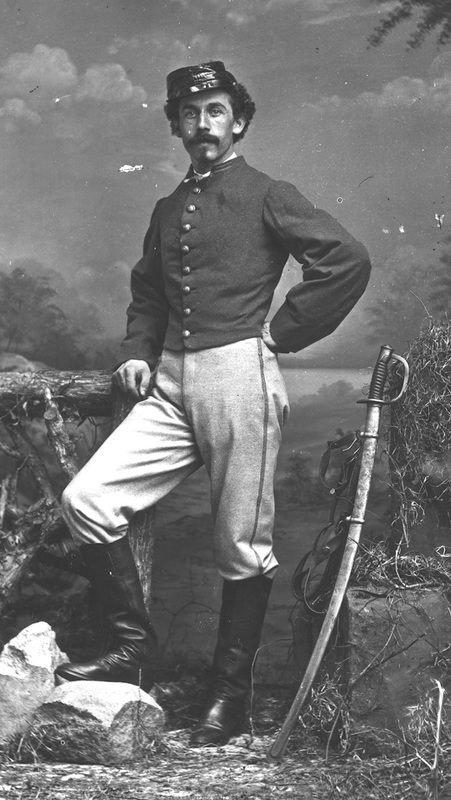

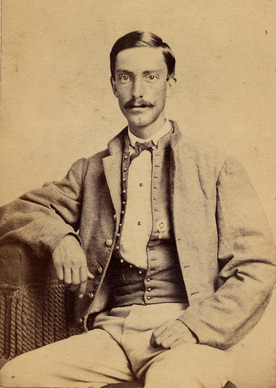

A few images survive that depict enlisted uniforms that appear to have been tailored from quartermaster-issued, cadet gray cloth. Three of these images show soldiers clearly wearing identical jackets and vests. These soldiers are Private Benjamin Bridge, Jr., Samuel Brooks Newman, Jr., and James Clarke, all of whom served with the Washington Artillery in the Mobile area until the surrender. The jacket and vest is made from matching fabric, probably cadet gray. The vest has fifteen small ball buttons. The jacket has seven federal eagle buttons, a red collar facing that has been applied over the existing collar, and cuffs without facings. Upon closer inspection, it appears that the jacket and vest is the same in each image and that the garments were photographer props, in which case they are not representative of the cadet gray uniforms made in Mobile. Clarke’s pants appear to be cadet gray kersey, as does Felix Arroyo’s jacket. These items may well have been tailored for these soldiers in Mobile. Arroyo’s pants and considerably darker than his jacket, and may be black citizen pants.[83]

Having examined all of the surviving clothing of the department’s depots, as well as numerous photographs, we can draw a few conclusions about the uniforms issued during the last year of the war. The quartermaster department managed to universalize its jacket patterns down to two from several different variants: the Anderson and the Montgomery, both made of gray-dyed, Southern-made woolen-cotton fabric. The department issued pants made of fabric that matched the jackets, but also produced natural white-colored trousers. The quartermaster made both simple, undyed wool felt hats with enamel cloth accessories, and caps with enamel visors (some of which had colored bands, and some that were left plain gray). Additionally, many troops received cadet gray cloth from the quartermaster, and had pants and jackets made from it.

The evidence in the study suggests that the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana had a superb clothing bureau by the middle of 1864. The department had ample clothing for its own troops, but it appears that it did not furnish troops outside the department with clothing. Apparently, the department did not even supply the Army of Tennessee with clothing after the Tennessee campaign. The provenance of the surviving original jackets bears out this assertion. Only two of the fifteen original Anderson and Montgomery jackets were worn by soldiers in the Carolina Campaign. These two are both Montgomery jackets. Theoretically, the Army of Tennessee troops were in a good position to get both Anderson and Montgomery uniforms in early 1865. The bedraggled army rested in the vicinity of Tupelo and Corinth, Mississippi, after its disastrous retreat out of Tennessee, having started to arrive there about January 2, 1865. E.T. Freeman, Inspector-General for Walthall’s Division, remarked of the army’s condition near Tupelo, January 10, 1865, “Nine-tenths of the men and line officers are barefooted and naked.”[84] General Richard Taylor, commander of the department by that time, inspected these troops in Tupelo from January 5 to 9, 1865, and remarked that they were in desperate need of blankets, shoes and clothing, especially in light of the severely cold winter weather. He began transporting them from Tupelo to Meridian, “…where timber for shelter, and fuel was abundant and supplies convenient; and every energy exerted to reequip them.”[85] Their need was acute, but there are no records recounting any clothing issues to them from Taylor. By January 16, 1865, roughly half of the Army of Tennessee commenced its move eastwards towards Augusta, Georgia, where it would begin its Carolina Campaign. The other half was reassigned to the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, where it would remain for the rest of the war. The portion that remained in Taylor’s department was very generously supplied with clothing from the Anderson and Montgomery Depots. The troops who went east may have gotten some clothing during their short rest in Mississippi, but the paucity of surviving jackets from the department suggests that few were issued. Perhaps the two surviving Montgomery jackets worn during the Carolina Campaign were issued as the troops passed through Montgomery on their journey east. It is also possible that the eastward-bound troops received new clothing at Augusta, Georgia, where they paused for short spell before continuing to North Carolina. They also received clothing from both Confederate and North Carolina State quartermasters once they arrived.

From the very beginning of the war, the region that would eventually encompass the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, had always been a hive of clothing manufacturing. Before New Orleans fell, the city’s factories provided copious quantities of uniforms to the troops training at Camp Moore and to the Army of Mississippi before the Battle of Shiloh. Most of the uniforms issued at Camp Moore were standardized and elaborate with shoulder straps, woolen tape embellishment, and nine (or more) front buttons. The New Orleans factories also produced simple, plain suits with jackets having but five buttons, and even cheaper suits of undyed and unbleached white woolen. From 1861 through 1864, Mississippi factories likewise produced large quantities of Confederate clothing. Judging from the uniforms that have survived from this period and region, each factory made its jackets and pants according to its own patterns, so there were distinctive variations in tailoring and the number of buttons per jacket. Most of the factories produced white woolen uniforms, but some used dyed cloth (steel gray or brown). The few surviving examples are rather plain and simple.

Notwithstanding the good will and energies of the quartermasters in this region, there were serious systematic problems with procurement, production and distribution. The clothing industry embodied an overall lack of standardization and efficiency. Manufacturers were not obligated to allot a percentage of their production to the military, and Confederate army procurement agents competed fiercely for scarce resources with state officials and private speculators, which hobbled their ability to obtain supplies. A lack of a district and department based clothing bureau led to regimental officers ranging far and wide to obtain clothing and equipage, causing an immense logistical burden upon the Southern war effort. For example, in 1862, Colonel Charles DeMorse, Commander of the 29th Texas Cavalry stationed in North Texas, travelled to Virginia, then to Georgia, and finally to Mississippi to procure clothing, arms, accoutrements, and equipment.[86] Likewise, in the same year, large depots frequently supplied troops in remote locations with clothing when local depots could have done so more efficiently. An example of this is the Columbus, Georgia Depot furnishing uniforms to armies in Arkansas, Mississippi and Virginia in late 1862.[87]

Confederate authorities recognized the systemic weaknesses with the Clothing Bureau, and were making improvements gradually. By 1862, manufacturing depots had been established and were well-functioning. The grossly inefficient commutation system was, therefore, officially abolished in October 1862. This move somewhat consolidated procurement and distribution into the hands of government quartermasters, but there were still egregious problems with procurement, as alluded to in the previous paragraph. In August 1863, Allen R. Lawton was appointed Quartermaster General for the Confederate Army.[88] Lawton had much business and logistics experience, and he had a vision for streamlining operations within the Clothing Bureau, gaining control over the countries resources through systematic procurement, and increasing production. His goal was to establish well-functioning, manufacturing depot centers, similar to Atlanta, throughout the South. To this end, he inspected Major George W. Cunningham’s operation in Atlanta, and then sent Cunningham, and Colonel Eugene E. McLean, to inspect the other depots of the Lower South in order to implement more efficiency into their operations. Lawton envisioned more systematic production methods; consolidation, standardization and quality control; and, stringent guidelines in the fabrication of clothing and equipment. Lawton believed that the South could be self-sufficient if it managed its resources efficiently. He wrote General Robert E. Lee in February 1864, “…our main reliance must be our home resources.”[89]

During their inspections of the Lower South, both Cunningham and McLean noted a lack of planning, poor use of resources, and problems with reliable procurement of materials. They reported on the overall fitness the quartermaster officers in charge of the various depots. In the case of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, McLean found that Captain William M. Gillaspie, in charge of the Selma Depot, was very capable. He found Captain Calhoun, in charge of the Montgomery Depot, to be mediocre, resulting in Calhoun’s re-assignment as post quartermaster at Marion, Alabama. McLean recommended the consolidation of all the Alabama and Mississippi clothing manufacturing establishments into one manufacturing operation managed out of Selma by Captain Gillaspie. McLean envisioned an operation similar to that of Atlanta. While this grand plan was never implemented, operations were consolidated within the two main districts. Operations in Selma, Montgomery, Cahaba and Tuscaloosa, Alabama were consolidated into one depot run out of Montgomery by Gillaspie. The Mississippi operations at Columbus, Jackson and Enterprise were consolidated under the charge of Major William J. Anderson at Columbus.[90] Nonetheless, both depots worked hand-in-glove to supply the department’s troops with clothing and equipment. Some degree of uniformity was achieved by adopting two standard uniforms (the Montgomery and the Anderson jackets) as opposed to the diversity that had existed prior to 1864.

Lawton achieved his vision. He resolved problems with procurement by requiring manufacturers to sell certain percentages of their production to the Confederate army. As Lawton explained to Congress on February 16, 1865, “…all the factories are under contract to deliver at fair rates two-thirds of their production,” and that he had implemented a “uniform system, one built up with care and labor, and with a result perfectly satisfactory.”[91] Lawton also stopped his depot officers in the Lower South from competing with one another by requiring them to request contracts for materials through a central office in Atlanta.[92] On December 12, 1864, Lawton reported of the Clothing Bureau, “…more clothing has been issued our armies in the field, the item of overcoats excepted, than either their comfort or efficiency demanded.” Quartermasters did not make overcoats due to the excessive amounts of cloth needed to make them, and blanket production was problematic due to almost a shortage of blanket making factories in the South. The Confederacy had to rely on imports for blankets throughout the war.[93] Aside from these two items, the Confederate soldier had plenty of shoes jackets, pants, shirts, socks and drawers by mid-1864. General Richard Taylor’s department reflects this plenitude. Specifically, General Dabney Maury’s command at Mobile received between 1 July and 30 November 1864 the following clothing: 21,789 jackets; 37,661 pairs of pants; 34,342 pairs of shoes; 4,677 blankets; 27,292 hats and caps; 10,098 cotton shirts; 3,831 pairs of drawers; and, 15,458 pairs of socks.[94]

Perhaps the most fitting tribute to the department’s contributions to clothing the Confederate soldier comes from one of the Southland’s foremost foes: General William Tecumseh Sherman. Sherman commented on the ability of the South to supply its armies twice in January 1863 while operating in Mississippi. In letters to his brother he wrote, “I suppose you are now fully convinced of the stupendous energy of the South and their ability to prolong this war indefinitely, but I am further satisfied that if it lasts 30 years we must fight it out, because the moment the North relaxes its energies the South assume the offensive and it is wonderful how well disciplined and provided they have their men. We found everywhere abundant supplies,… and the soldiers, though coarsely, are well clad. We hear of the manufacture of all sorts of cloth and munitions of war.” He continued, “The South abounds in corn, cattle and provisions and the progress in manufacturing shoes and cloth for the soldiers is wonderful. They are as well supplied as we and they have an abundance of the best cannon, arms and ammunition. In long range cannon they rather excel us and their regiments are armed with the very best Enfield rifles and cartridges, put up at Glasgow, Liverpool and their own Southern armories, and I still say they have now as large armies in the field as we. They give up cheerfully all they have. I still see no end or even the beginning of the end…”[95]

Acknowledgements:

The author extends his thanks to numerous institutions and people for their generous cooperation and indispensable help with this study. Les Jensen’s Survey of Government Made Confederate Jackets, published in 1989, provided the first study of the “Alabama” (Anderson-style) jackets. Harold S. Wilson’s Confederate Industry provided an understanding for clothing bureau operations. Tom Arliskas’s Cadet Gray and Butternut Brown provided invaluable insights on the uniforms. Numerous institutions and individuals have shared their collections, insights, and valuable time with me to make the study possible. These include The Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, Chief Curator, Robert Hancock; Alabama Confederate Memorial Park, Marbury, Alabama, Director Bill Rambo; Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama, Bob Bradley and Dr. Kerr; Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Executive Director Ray Richey; Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana, Director Pat Ricci; Washington Artillery of New Orleans website and Glen C. Cangelosi collection; Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana, Chief Curator Wayne Phillips; Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia, Curator Heather Beattie; Museum of Southern History, Houston Baptist University, Houston, Texas, Curator Maggie Brown; General Sweeny’s Civil War Museum, Republic, Missouri, Dr. Tom Sweeney and Joseph Furtak; Wilson Creek National Battlefield, Republic, Missouri, Curators Deborah Wood and Alan Chilton; Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Curator Paul Shevchuk; Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, Curator Margaret Vining; South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina, Curator Joe Long; Neill Rose, Camden, South Carolina; Alan Hoeweller collection, Cincinnati, Ohio; Samuel P. Higginbotham II collection, Orange, Virginia; Lawrence T. Jones III, Confederate Calendar, Austin, Texas; Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III collection, Dallas, Texas; Old Courthouse Museum, Vicksburg, Mississippi, Gordon A. Cotton and Jeff T. Giambrone; J.S. Mosby Antiques & Artifacts, Orange, Virginia, Stephen W. Sylvia; Historian Mike Bailey, Fort Morgan Historic Site, Gulf Shores, Alabama; Collecting the Confederate Soldier, Jim Osborn, Rockywood Productions, Inc., Denver, Colorado, 1996, Richard Todd collection; Archivist Vicki Betts, University of Texas, Tyler, online newspapers; Washington Memorial Library, Macon, Georgia, Brett Boyd and Anne Rogers; Military Images, Editor Ron Coddington, Arlington, Virginia; North South Trader Civil War, Publisher Steve Sylvia, Orange, Virginia; the Pink Palace Museum, Memphis, Tennessee; and, an anonymous private collection by wishes of the owner.

Copyright:

All photos are copyrighted to Adolphus Confederate Uniforms. Although the artifacts are credited to different institutions, the images themselves are the property of the website and may not be reproduced without the author’s consent.

Bibliography:

[60] Artifact in the collection of the Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Author examined the trousers on 17 December 2010.

[61] Artifact in the collection of the Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Author examined the trousers on 17 December 2010.

[62] Artifact in the collection of the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina. Observations made from photographs provided by Neill Rose, Camden, South Carolina.

[63] Artifact in the collection of the National Battlefield Park, Wilson’s Creek, Missouri. Author examined the jacket on 31 October 1998 while it was part of Dr. Sweeney’s collection in Republic, Missouri; and, again in August 2011 at Wilson’s Creek.

[64] CSRs Alabama, M311, Roll 25, C.W. Mitchell.

[65] Artifact in the collection of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, Confederate Memorial Park, Marbury, Alabama; pants worn by C.W. Mitchell, Company F, 7th Alabama Cavalry. Author examined the trousers in April 2103, and 10 February 2015.

[66] CSRs Louisiana, M320, Roll 361, N. Tisdale; accession records, Confederate Memorial Hall.

[67] Artifact in the collection of Confederate Memorial Hall collection, New Orleans, Louisiana; Catalog # 007.001.015c, drab colored trousers of Private Nathan Tisdale, Company A, 30th Louisiana Infantry Regiment. Author examined the trousers on 2-3 November 1998; 10 September 2009; and, 12 November 2010. See also for comparison of similar Lower South factory trousers with watch-style pockets the Catalog Number U-083 pants in the Armed Forces History Division, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Charles Bremner Hogg Jackson collection, Accession Number 1980.0399 (Catalog Number U-082 jacket, and Catalog Number U-083 pants).

[68] Image of the “unidentified Louisiana Zouave” from the collection of the Virginia Historical Society; images of J.A. Chalaron, Benjamin Bridge, Jr., and Samuel Brooks Newman, Jr. 5th Company Washington Artillery, from the Glen C. Cangelosi collection and the Washington Artillery of New Orleans website, http://www.washingtonartillery.com; CSRs Louisiana, M320, Roll 63, Benjamin Bridge, Jr. and B. Bridge, Jr. (who was inexplicably admitted to a general hospital in Richmond, Virginia on March 27 1964), Co. 5; and, Roll 68, Samuel Brooks Newman, Jr. and S.B. Newcomb, Co. 5.

[69] Image courtesy of the Glen C. Cangelosi collection and the Washington Artillery of New Orleans website, http://www.washingtonartillery.com; CSRs Louisiana, M320, Roll 63, James Clarke and James Clark, Co. 5.

[70] Howell, H. Grady, Going to Meet the Yankees: A History of the “Bloody Sixth” Mississippi Infantry, C.S.A., Chickasaw Bayou Press, 1981, see the cumulative issues for the regiment in the appendices.

[71] The Last Campaign: A Cavalryman’s Journal by E.N. Gilpin, Third Iowa Cavalry, Reprint from The Journal of the U.S. Cavalry Association, p. 646.

[72] Artifact in the collection of Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana. Cap, catalog # 7.3.160a; rain cover, catalog # 7.3.160b; provenance 1st Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron, 5th Company, Washington Artillery. Author examined the cap and cover on 17 November 2000; 9 August 2002; 10 September 2009; and, 12 November 2010.

[73] CSRs Alabama, M311, Roll 327, Arthur A. Crews and A.A. Crews.

[74] Artifact in the collection of the Museum of the Confederacy collection, Richmond, Virginia. Author examined the cap on 24 July 2012, and 14-15 October 2013.

[75] Military Images, Vol. XXI, No. 3, Nov-Dec 1999, p. 38, Carte de visite by “Ben Oppenheimer, 55-66 Daupin Street, Mobile”, May 1865; photo courtesy of Charles Anegan.

[76] Three versions of the same CDV of Robert W. Frazer survive. One in the collection of Confederate Memorial Hall, Catalog # 001.005.570. Another is in the collection of J.S. Mosby Antiques & Artifacts, reference Civil War Collector’s Price Guide 11th Edition, p. 234. The third is in the Glen C. Cangelosi collection.

[77] Image courtesy of the Glen C. Cangelosi collection and the Washington Artillery of New Orleans website, http://www.washingtonartillery.com; CSRs Louisiana, M320, Roll 70, W.W. Sewell, Co. 5.

[78] Image of the “unidentified Louisiana Zouave” courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society; image of Felix Arroyo courtesy of the Glen C. Cangelosi collection and the Washington Artillery of New Orleans website, http://www.washingtonartillery.com; CSRs Louisiana, M320, Roll 62, Felix Arroyo, Co. 5.

[79] Artifact in a private collection. Author examined the jacket on 27 July 2015. See also North South Trader, Vol. XIV, No. 1, Nov-Dec 1986, pp. 16-18.

[80] CSRs Louisiana, M320, Rolls 50, 97 and 99, R.H. Brunet, Jr. and J.W. Noyes; their organization started as 1st Special Battalion (Rightor’s) Louisiana Infantry, and re-organized as Captain Fenner’s Battery, Louisiana Light Artillery in 1862.

[81] Artifacts in the collection of the Museum of Southern History, Houston Baptist University, Houston, Texas. Author examined the jacket and pants in May 1885; May 1996; 14-15 November 1998; 17 July 2003; 21 November 2012; 20 March 2013, and 3 November 2015.

[82] Artifact in the collection of Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana. Author examined the jacket on 2-3 November 1998; 9 August 2002; 10 September 2009; 12 November 2010; 14 November 2014; and, 27 October 2015.

[83] Images courtesy of courtesy of the Glen C. Cangelosi collection and the Washington Artillery of New Orleans website, http://www.washingtonartillery.com.

[84] ORs, Series 1, Volume 45, Part 2, Chapter 57, page 775, Headquarters, Walthall’s Division, near Tupelo, Mississippi, January 10, 1865, E.T. Freeman, AAIG, to General French.

[85] Taylor, Richard, Destruction and Reconstruction, Personal Experiences of the Late War, New York, 1900, p. 217.

[86] Felmly, Bradford K. and Grady, John C., Suffering to Silence: 29th Texas Cavalry, CSA Regimental History, Nortex Press, Quanah, Texas, 1975, pp. 13-17.

[87] The Columbus Depot sent 7,000 garments to the Army of Arkansas; six car loads of garments and shoes to Richmond, Virginia; and, another 5,000 garments to the Army of Western Virginia in the fall of 1862. Waul’s Texas Legion and the First Missouri Brigade reported being supplied with Columbus-style uniforms (“grey jackets with blue collars and cuffs”), in northern Mississippi, as well. See the letters of Captain Robert Voigt, Commander, Company C, 1st Battalion, Waul’s Legion, November 3, 1862, Center for American History, University of Texas, Austin; Bevier, R.S., History of the First and Second Missouri Confederate Brigades, 1861-1865, Bryan, Brand & Company, St. Louis, 1879, re-printed by The Inland Printer Limited, 1985, p. 166; Columbus Daily Sun, Georgia, September 16, 1862, and other fall reports.

[88] Brigadier General A.R. Lawton was officially appointed Quartermaster General on February 17, 1864, but he effectively took control of the Clothing Bureau from his predecessor, Colonel Abraham C. Myers, in August 1863 by virtue of out ranking Myers; CSRs Officers, M331, Roll 154.

[89] Wilson, p. 125, n. 151. While noting key reforms in the Clothing Bureau in this brief synopsis, Harold S. Wilson has a full account in “Confederate Industry,” my chief source for this part of the study.

[90] Wilson, pp. 103-104, n. 32 and 33; and CSRs Officer, M331, Roll 7 and 106.

[90] Wilson, pp. 128-129, n. 175.

[92] CSRs Officer, M331, Roll 68, Circular, Confederate Quartermaster General’s Office, Richmond, Virginia, April 23, 1864, A.R. Lawton, Quartermaster General; reference courtesy of Wilson, p. 105, n. 43.

[93] Wilson, p. 125, n. 152 and 155; p. 127, n. 168; p. 128, n. 171; Lawton wrote, “…with the exception of overcoats, which have not been made up, owing to the great consumption of woolen material for jackets and pants, and the item of flannel undershirts but partially supplied, the armies have been fully supplied.”

[94] Wilson, p. 127, from OR, Series 4, Volume 3, pp. 1039-1041, A.R. Lawton, C.S. Quartermaster General’s Office, Richmond, to Hon. Mr. Miller, Chairman Special Committee, January 27, 1865.

[95] Thorndike, Rachel Sherman, editor, The Sherman Letters: Correspondence between General and Senator Sherman from 1837 to 1891, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1894, page 180, January 6, 1863, and, page 185, January 25, 1863. Reference courtesy of Wilson, p. 190, note 48, p. 347.