Confederate Uniforms of the Lower South, Part V: Miscellaneous Clothing from the Region at Large

By Fred Adolphus, September 27, 2019 (updated 19 April 2023)

Continued from Part IV: click here to navigate back to the previous page...

Numerous Confederate jackets survive that defy categories, chiefly because they are one-of-a-kind. Perhaps some represent the sole survivors of small production runs, but since there are no others like them with which to compare, we cannot draw broader conclusions. Jackets of this type with provenance to the Lower South have been selected for this study. I have included five such jackets that may have been factory made.

Two of these jackets that share no distinct characteristics with any other known depot variants include a plain, butternut jacket and a jeans jacket with two exterior pockets. The butternut jacket is without provenance, but the other was worn by Captain George Little, an ordnance officer in Cheatham’s Corps, Army of Tennessee.[206] Little wore this jacket when he was wounded in the Tennessee Campaign of late 1864. This accounts for the sizable swath of fabric that was cut from the left front shoulder to access and treat his wound. The butternut jacket was likewise in poor condition due to both field use and gradual deterioration, but expert conservator, Jessica Hack, restored it to a splendid condition. Both jackets have eight-button fronts and a facing welt of basic cloth along the bottom, inside edge of the body. They have unbleached osnaburg linings and curved front lapel bottoms. The butternut jacket has no exterior pockets. Its color cannot be closely examined in the images, so it may have either been made in its medium light, butternut brown color, or it may have faded from a gray color. The Little jacket is a steel gray color with a brindled wool yarn weft. It has topstitching around the body, a two-piece collar and two-piece sleeves. The collar has been adorned with Little’s captain rank made from individual pieces of quarter-inch gold braid. The crudely attached braid might be indicative of how an officer would bring his enlisted jacket into compliance with regulations. At some point, perhaps even post-war, Federal general service, enlisted buttons were attached to the jacket (of which only a few remain intact).

Numerous Confederate jackets survive that defy categories, chiefly because they are one-of-a-kind. Perhaps some represent the sole survivors of small production runs, but since there are no others like them with which to compare, we cannot draw broader conclusions. Jackets of this type with provenance to the Lower South have been selected for this study. I have included five such jackets that may have been factory made.

Two of these jackets that share no distinct characteristics with any other known depot variants include a plain, butternut jacket and a jeans jacket with two exterior pockets. The butternut jacket is without provenance, but the other was worn by Captain George Little, an ordnance officer in Cheatham’s Corps, Army of Tennessee.[206] Little wore this jacket when he was wounded in the Tennessee Campaign of late 1864. This accounts for the sizable swath of fabric that was cut from the left front shoulder to access and treat his wound. The butternut jacket was likewise in poor condition due to both field use and gradual deterioration, but expert conservator, Jessica Hack, restored it to a splendid condition. Both jackets have eight-button fronts and a facing welt of basic cloth along the bottom, inside edge of the body. They have unbleached osnaburg linings and curved front lapel bottoms. The butternut jacket has no exterior pockets. Its color cannot be closely examined in the images, so it may have either been made in its medium light, butternut brown color, or it may have faded from a gray color. The Little jacket is a steel gray color with a brindled wool yarn weft. It has topstitching around the body, a two-piece collar and two-piece sleeves. The collar has been adorned with Little’s captain rank made from individual pieces of quarter-inch gold braid. The crudely attached braid might be indicative of how an officer would bring his enlisted jacket into compliance with regulations. At some point, perhaps even post-war, Federal general service, enlisted buttons were attached to the jacket (of which only a few remain intact).

Two more jackets appear to be depot products from the Lower South, but little is known about them. The first of these is attributed to a soldier named Hendy [72-4] who was killed at the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads with Forrest’s command on June 10, 1864. A search for a service record with this name proved fruitless making it impossible to verify the story.[207] In any case, the jacket is made of a light-weight, twill weave fabric, now a tan color. There are two notable features of this jacket. It was made without a lining with felled seams and it has olive green facings on the collar and cuffs. The green facings appear to be of the same material used for the green facings of the Silas Buck jacket. Buck has documented service with Forrest’s cavalry. The only difference in the facings is the coloration. Buck’s facings are a bolder, darker emerald green. Hendy’s facings appear to have faded to a lighter olive green. Hendy’s jacket has nine Federal general service, enlisted buttons and an interior, patch pocket made of the basic cloth. The jacket front and collar are topstitched as are the cuff facings, top and bottom. Despite the jacket’s weak provenance, it might support a theory that General Nathan Bedford Forrest had the quartermaster provide his command with green-trimmed jackets.[208]

The second of these jackets has red facings and sergeant major chevrons and is without any provenance. Regardless, the jacket appears authentic and has all the characteristics of a depot-made garment. It has a six-piece body, two-piece sleeves, two-piece collar and a six-button front. The buttons are imported, stippled, Roman “A” (Tice CSA200A1) made by HB&T, Manchester, England. The basic cloth is a sheep-gray colored woolen with a heavy nap, making the weave indiscernible. The lining appears to be an unbleached osnaburg. The bright scarlet, wool flannel facings and chevrons were added to the jacket after it was issued. The chevrons were applied directly to the sleeves without having first been sewn to a backing. The facings were whipstitched in place and the topstitched all around their edges. The entire jacket body has a row of topstitching.[209]

The second of these jackets has red facings and sergeant major chevrons and is without any provenance. Regardless, the jacket appears authentic and has all the characteristics of a depot-made garment. It has a six-piece body, two-piece sleeves, two-piece collar and a six-button front. The buttons are imported, stippled, Roman “A” (Tice CSA200A1) made by HB&T, Manchester, England. The basic cloth is a sheep-gray colored woolen with a heavy nap, making the weave indiscernible. The lining appears to be an unbleached osnaburg. The bright scarlet, wool flannel facings and chevrons were added to the jacket after it was issued. The chevrons were applied directly to the sleeves without having first been sewn to a backing. The facings were whipstitched in place and the topstitched all around their edges. The entire jacket body has a row of topstitching.[209]

From start to finish, homemade clothing supplemented the Confederate soldier’s wardrobe. During the first year-and-a-half of the war, the army relied greatly upon what families and volunteer societies made for individual soldiers, volunteer companies and the quartermaster. As the war progressed, the volunteer societies largely ceased operating, but families continued to make clothing for their loved ones in the service. Oftentimes, the only clothing that the Southern soldier received was that which his home folk sent him. Truth be told, the Southern soldier usually preferred the clothes he got from home over those from the quartermaster. The homemade clothes probably fit better than their army clothes and could be ordered to suit their individual tastes. Henry Orr of the 12th Texas Cavalry asked his mother to send his brother Robert “a frock or dress coat” and him “a dress or sack [coat] of the loose wrapper style,” in either gray or brown jeans, as well as cotton shirts and over shirts with pockets. Orr preferred the homemade coats to the short, issue jackets that they drew from the quartermaster.[210] British Lieutenant Colonel James Fremantle, while visiting the Army of Tennessee on May 31, 1863, remarked that Liddell’s Arkansas Brigade was “well clothed, though without any attempt at uniformity in color or cut; but nearly all were dressed either in gray or brown coats and felt hats,” and that “…even if a regiment was clothed in proper uniform by the government, it would become partli-colored again in a week, as the soldiers preferred wearing the coarse homespun jackets and trousers made by their mothers and sisters at home.”[211] Indeed, the story of Confederate clothing in the Lower South is not complete without including the homemade clothes that the troops wore.

Citizen frock and sack coats were well liked, and even though these garments were not military, they were welcomed into the ranks. Some examples include one worn by a soldier named Magee in the 7th Mississippi Infantry, and J.A. Chalaron, 5th Company, Louisiana Washington Artillery. Magee’s frock is made of the same Mississippi cloth used in government-made, enlisted soldier suits, being identical to that of the Smithsonian Institution U-083 pants. Chalaron’s citizen-style sack coat has red welts that show his artillery affiliation and the fabric matches that of his depot-made enlisted cap, suggesting that he purchased the cloth for the coat from the quartermaster.[212]

Citizen frock and sack coats were well liked, and even though these garments were not military, they were welcomed into the ranks. Some examples include one worn by a soldier named Magee in the 7th Mississippi Infantry, and J.A. Chalaron, 5th Company, Louisiana Washington Artillery. Magee’s frock is made of the same Mississippi cloth used in government-made, enlisted soldier suits, being identical to that of the Smithsonian Institution U-083 pants. Chalaron’s citizen-style sack coat has red welts that show his artillery affiliation and the fabric matches that of his depot-made enlisted cap, suggesting that he purchased the cloth for the coat from the quartermaster.[212]

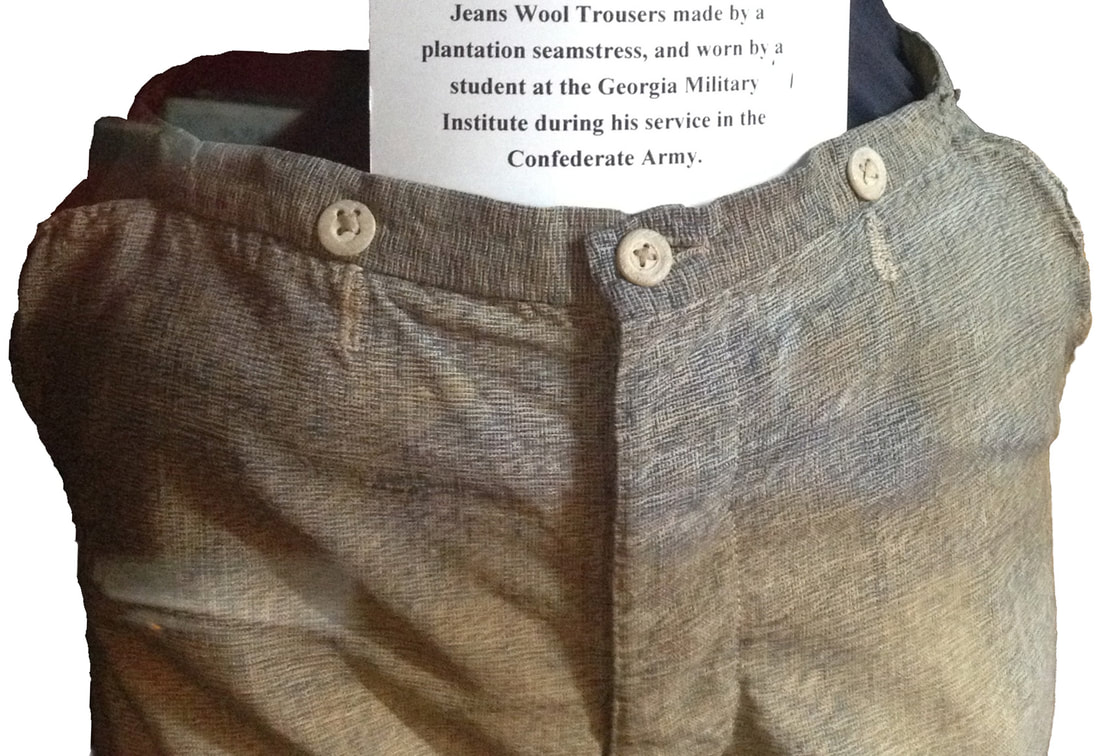

The home folks also made their own versions of the army jacket for cadets and soldiers alike. Archibald Smith’s and John McNish Hazlehurst’s cadet uniforms are some of these. Both these young men attended the Georgia Military Institute in Marietta, and both served with the Corps of Cadets during the Atlanta Campaign of 1864.[213] A pair of homemade pants attributed to an unnamed Georgia Military Institute cadet has an interesting story. It has been re-tailored from a pair of out-of-fashion, fall-front citizen pants to a pair with a fly.[214] The last cadet jacket from the Lower South was owned by Charles Locke Beard, who attended Florida Military Institute in Tallahassee in 1865. The seven-button, cotton jacket is a very light tan, believed to have faded from gray. The buttons are Louisiana pelican, backmarked, Hyde & Goodrich, New Orleans. Beard wore the jacket at the Battle of Natural Bridge, March 6, 1865. Other typical homemade jackets used by regular troops include those of Private Edward R. Oldham, Company M, 7th (Duckworth’s) Tennessee Cavalry, and Captain Thomas Feam Perkins, Company I, 11th Tennessee Cavalry, Forrest’s command.[215]

It would be remiss not to include the Confederate enlisted, single-breasted frock coat in a comprehensive study of the Lower South’s uniforms. This garment was not fated to last out the war, yet it rather went the way of the Confederate first national, “Stars and Bars” flag: never entirely disappearing but being encountered less and less by the middle of the war. Nevertheless, soldiers wore this garment to the very end, and the frock coat became iconic due to its prolific usage from 1861 and 1862 with so many surviving images of Confederate troops wearing it. What is problematic for this topic is the frock coat’s varied modes of procurement. Some were made by local sewing societies for local volunteer companies, some were homemade and some were made under the auspices of the Confederate quartermaster as a mass-produced garment. It is difficult to know which origin a given frock coat has without detailed provenance. Nonetheless, surviving enlisted frock coats deserve to be placed in their proper historical context.

The enlisted frock coat was undoubtedly the most popular and universal military garment in America by the start of the Civil War. Volunteer companies overwhelmingly adopted the frock from early 1861 to mid-1862. It was the most widespread uniform of its day being based upon the M1851 US army frock coat. The M1851 frock’s chief features were its collar and pointed cuff facings in the branch-of-service color, as well as its nine-button front. The Confederates used their own trim colors, and made their frocks in blue-gray, steel-gray or brown instead of dark blue. An eight- or nine-button front was common, but as tailors felt that frocks could get by with less, these were often reduced to six- or seven-button fronts. Southerners also frequently lengthened the skirt to the top of the knee to conform with the prevailing fashion trend. So engrained was the use of the M1851-style frock coat that most volunteer organizations selected it over the double-breasted, short-skirted frock prescribed by Confederate uniform regulations. The frock coat achieved a surprising degree of uniformity throughout the South, from Virginia to Texas.

From the very beginning, the Confederate quartermaster department prescribed short jackets instead of either the regulation, double-breasted tunic, or the M1851-style frock coat. Despite this, some early quartermaster operations made single-breasted frock coats. The Little Rock Depot is well documented as having made gray or brown jeans frocks with black or dark blue facings.[216] The New Orleans and Nashville quartermasters probably contracted for some, and they issued fair amounts, but most of these were probably supplied in spite of, rather than because of, specifications for frocks. The overwhelming number of frocks were made by private sources for the early volunteer companies, rather than though official quartermaster channels. Some of the sources, such as volunteer societies, donated frocks to the quartermaster in Tennessee. In this way, they ended up in the supply chain, thereby becoming de facto, depot clothing.

It comes as no surprise that the jacket quickly replaced the frock coat. The jacket could be made in less time and with less expenditure of materials than the costly frock coat. Indeed, the Confederate Quartermaster General, Abraham Meyers, mandated the universal adoption of the jacket before the official uniform regulations were even published. On May 31, 1861, Meyers called for the quartermaster in New Orleans to furnish jackets rather than tunics. Meyers first asked for 5,000 gray jackets and pants to be furnished, “…or any color you can get…” On 5 June he again asked that jackets and trousers be manufactured as the standard Confederate uniform.[217] His intent was that all quartermasters acquire jackets instead of frocks, and that private manufactures and local clothing aid societies make jackets in lieu of frocks, as well.

Meyers’ prescribed jacket made perfect sense, and by the summer of 1861, most factories and quartermasters had switched to the jacket to save materials, production time and overall costs. Official quartermaster records indicate that frocks were rarely mass-produced, and even during the summer of 1861, when the first mass-produced, Confederate quartermaster clothing was made, the jacket was the standard soldier’s tunic. The single-breasted, enlisted frock coat was destined to fade away. The short shell jacket became the typical Confederate uniform and informed the image of the Confederate soldier. That said, a brief look at enlisted frock coats will help round out the story of the Confederate uniform in the Lower South: from the early muster uniforms to the late-war homemade frocks.

Three enlisted, single-breasted frocks appear to be early war products of the South Carolina Quartermaster. The first (an eight-button frock) was worn by Robert Hayne Bomar, Company B, 25th South Carolina Infantry, from June 1861 until his medical discharge in March 1862.[218] Bomar’s frock is a warm, medium brown color with light yellow braid edging the collar. The braid’s yellow color may be the result of having faded from another color. The next was worn by Joseph Ellison Adger, Company A, 25th South Carolina Infantry. Adger acquired his seven-button frock as an enlisted man and from 1862 continued to wear it as an officer.[219] Adger’s frock is steel gray with black braid and edging for trim. The third uniform of frock and trousers was worn by James Wiley Gibson, 2nd South Carolina Artillery. Gibson wore his seven-button frock and matching trousers until the Battle of Secessionville, where he was killed on June 16, 1862. Gibson’s frock and pants are light brownish-gray in color and the coat has the same shade of yellow braid on the collar as seen on Bomar’s coat. All the coats have tape trim on the collars, and Gibson’s has it on the cuffs, as well; which is consistent with the state-issue uniforms for the first year of the war.[220]

The enlisted frock coat was undoubtedly the most popular and universal military garment in America by the start of the Civil War. Volunteer companies overwhelmingly adopted the frock from early 1861 to mid-1862. It was the most widespread uniform of its day being based upon the M1851 US army frock coat. The M1851 frock’s chief features were its collar and pointed cuff facings in the branch-of-service color, as well as its nine-button front. The Confederates used their own trim colors, and made their frocks in blue-gray, steel-gray or brown instead of dark blue. An eight- or nine-button front was common, but as tailors felt that frocks could get by with less, these were often reduced to six- or seven-button fronts. Southerners also frequently lengthened the skirt to the top of the knee to conform with the prevailing fashion trend. So engrained was the use of the M1851-style frock coat that most volunteer organizations selected it over the double-breasted, short-skirted frock prescribed by Confederate uniform regulations. The frock coat achieved a surprising degree of uniformity throughout the South, from Virginia to Texas.

From the very beginning, the Confederate quartermaster department prescribed short jackets instead of either the regulation, double-breasted tunic, or the M1851-style frock coat. Despite this, some early quartermaster operations made single-breasted frock coats. The Little Rock Depot is well documented as having made gray or brown jeans frocks with black or dark blue facings.[216] The New Orleans and Nashville quartermasters probably contracted for some, and they issued fair amounts, but most of these were probably supplied in spite of, rather than because of, specifications for frocks. The overwhelming number of frocks were made by private sources for the early volunteer companies, rather than though official quartermaster channels. Some of the sources, such as volunteer societies, donated frocks to the quartermaster in Tennessee. In this way, they ended up in the supply chain, thereby becoming de facto, depot clothing.

It comes as no surprise that the jacket quickly replaced the frock coat. The jacket could be made in less time and with less expenditure of materials than the costly frock coat. Indeed, the Confederate Quartermaster General, Abraham Meyers, mandated the universal adoption of the jacket before the official uniform regulations were even published. On May 31, 1861, Meyers called for the quartermaster in New Orleans to furnish jackets rather than tunics. Meyers first asked for 5,000 gray jackets and pants to be furnished, “…or any color you can get…” On 5 June he again asked that jackets and trousers be manufactured as the standard Confederate uniform.[217] His intent was that all quartermasters acquire jackets instead of frocks, and that private manufactures and local clothing aid societies make jackets in lieu of frocks, as well.

Meyers’ prescribed jacket made perfect sense, and by the summer of 1861, most factories and quartermasters had switched to the jacket to save materials, production time and overall costs. Official quartermaster records indicate that frocks were rarely mass-produced, and even during the summer of 1861, when the first mass-produced, Confederate quartermaster clothing was made, the jacket was the standard soldier’s tunic. The single-breasted, enlisted frock coat was destined to fade away. The short shell jacket became the typical Confederate uniform and informed the image of the Confederate soldier. That said, a brief look at enlisted frock coats will help round out the story of the Confederate uniform in the Lower South: from the early muster uniforms to the late-war homemade frocks.

Three enlisted, single-breasted frocks appear to be early war products of the South Carolina Quartermaster. The first (an eight-button frock) was worn by Robert Hayne Bomar, Company B, 25th South Carolina Infantry, from June 1861 until his medical discharge in March 1862.[218] Bomar’s frock is a warm, medium brown color with light yellow braid edging the collar. The braid’s yellow color may be the result of having faded from another color. The next was worn by Joseph Ellison Adger, Company A, 25th South Carolina Infantry. Adger acquired his seven-button frock as an enlisted man and from 1862 continued to wear it as an officer.[219] Adger’s frock is steel gray with black braid and edging for trim. The third uniform of frock and trousers was worn by James Wiley Gibson, 2nd South Carolina Artillery. Gibson wore his seven-button frock and matching trousers until the Battle of Secessionville, where he was killed on June 16, 1862. Gibson’s frock and pants are light brownish-gray in color and the coat has the same shade of yellow braid on the collar as seen on Bomar’s coat. All the coats have tape trim on the collars, and Gibson’s has it on the cuffs, as well; which is consistent with the state-issue uniforms for the first year of the war.[220]

Two uniforms are representative of those made for the Confederate Quartermaster in New Orleans. The first is Joseph B. Phillips seven-button, light gray jeans frock with shoulder straps and tape trim. His accompanying light blue jeans pants with colored edging survive, as well. Phillips served with Company A, Louisiana Crescent Regiment and wore the uniform from March 1862 until his death on June 3, 1862 in Tupelo, Mississippi. His mother was present when he died and she took his affects, to include his uniform.[221] A similar steel gray, nine-button jeans frock attributed to an unidentified Louisiana soldier has the same characteristics. It has shoulder straps, black wool tape trim and Louisiana state pelican buttons. Both these frocks follow the general pattern used in making the “Camp Moore” uniforms and represent the extravagance indulged prior to the enforced austerity represented by the simpler jacket.[222]

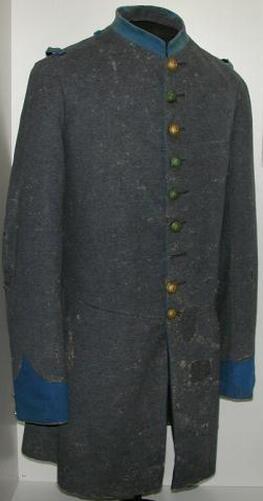

Three frocks document the early production of the Nashville quartermaster operation. The first was worn by Samuel Blake Ryan of the 5th (later the 9th) Kentucky Infantry. Ryan wore his light gray, eight-button frock during his service that spanned from September 1861 until his medical discharge in September 1862, having been severely wounded at Shiloh. It has black trim on the cuffs but not the collar.[223] The next frock was worn by Charles Christopher Harris Williams, Company D, 27th Tennessee Infantry, from 1861 to 1862. Williams’ light gray, nine-button frock has black trim on the collar but not the cuffs. Williams started his service as a captain and was soon elected as the regiment’s colonel. Nonetheless, his frock coat appears to have been an early Nashville Depot, enlisted issue uniform.[224] The last of these was worn by Henry C. Hall, 4th Kentucky Infantry at the Battle of Murfreesboro, when he was killed on January 2, 1863. Hall may have received the frock at the time of his enlistment in August 1861. Hall’s steel gray, nine-button frock has light blue trim on the collar and cuffs.[225]

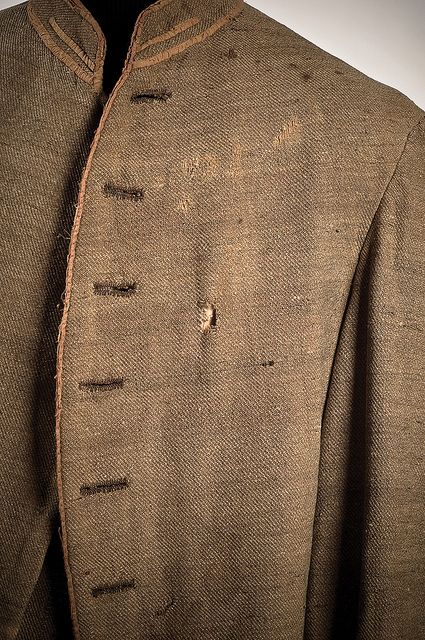

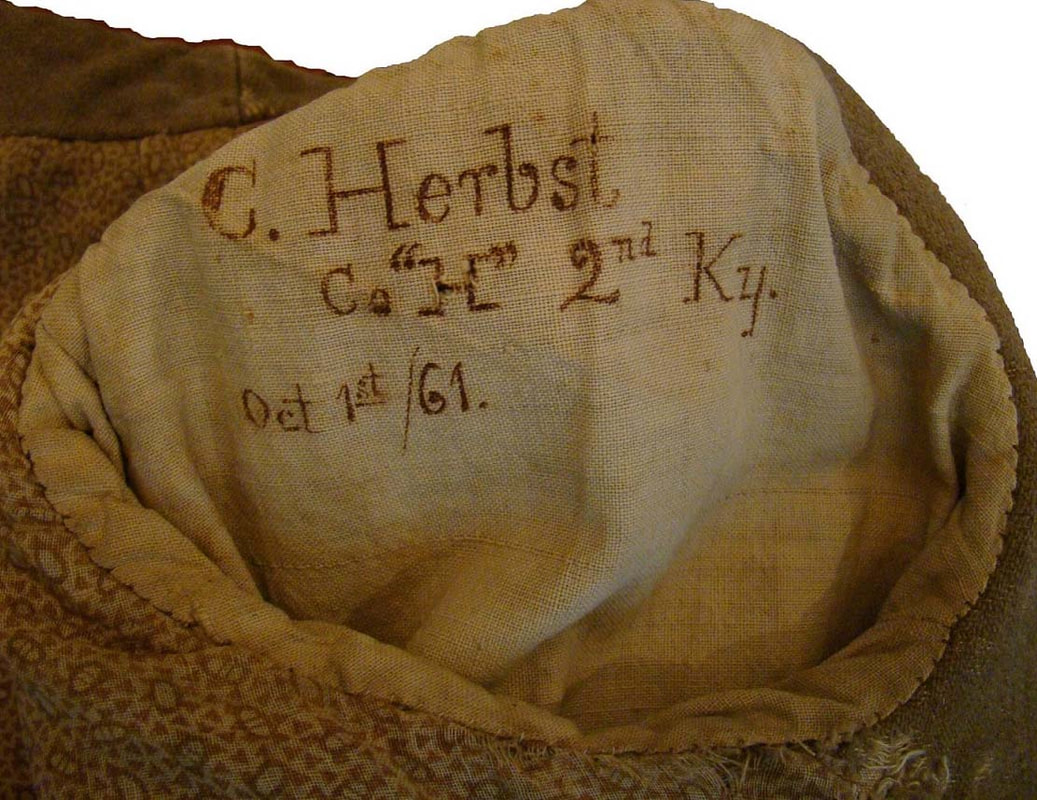

Several frocks with late war provenance appear to be homemade, attesting to the garment’s popularity, if not the quartermaster’s ability to keep it in production throughout the war. None of these examples have colored facings or tape trimmings. The first of these was worn by one of the Martin brothers in Company E, 6th Georgia Infantry: either Alfred W. or Thomas Jefferson Martin. Thomas was probably the owner of the coat, considering that he was wounded at “Cool Harbor,” Virginia, June 2, 1862, and the coat has bullet holes corresponding to entry and exit wounds in the left shoulder. It seems likely that a wounded man would have kept the coat as a souvenir. Had Alfred owned the coat, he would most likely have been buried in it, having been killed at the Battle of Sharpsburg that same year. The six-button frock is made of satinet and its medium-dark brown color suggest that the woolen yarns were home-dyed with walnut hulls. Its large, Courtney & Tennant, Roman A buttons (Tice CSA203A1), with Superior Quality backmarks, are a mystery since the Martins were not artillerymen.[226] Charles Lee Neely wore his seven-button frock with a partial red flannel lining when killed at Brice’s Crossroads, June 1864, fighting with Forrest’s command.[227] Charles Herbst of the 2nd Kentucky Infantry is thought to have received his eight-button, button frock after the Battle of Dallas, Georgia in June 1864. Herbst’s coat is lined with a brown-colored, floral print fabric that is more common to homemade coats.[228] James L. Cooper, Company C, 20th Tennessee Infantry, wore his six-button frock at Franklin and Nashville in late 1864. Cooper was appointed Aide-de-Camp to General Tyler in July 1864, and as such, would have acted in the capacity of an officer, but he probably wore it while he was an enlisted man, prior to his promotion.[229] Finally, Sergeant Thomas Norwood Kelly, Companies E and H, 5th South Carolina Infantry, wore his seven-button frock when he was wounded at the Wilderness, May 6, 1864. His mother mended the coat while he was at home recuperating from his wound. The medium brown coat’s most notable feature is its fall collar.[230]

91e. The inside tailoring features the very wide lapel facing pieces that incorporate the entire front piece components of the lining. The wide, basic cloth facings are an extravagance that could be afforded by family making a homemade garment. Government manufactured garments practiced more frugality and eschewed using such generous quantities of basic cloth in lieu of cheaper cotton osnaburg.

The final uniform to be considered is the double-breasted enlisted frock coat. This design was the officially sanctioned Confederate enlisted tunic, but due to its expense in time and materials to manufacture, the Quartermaster Department replaced it with the single-breasted jacket. Nonetheless, the regulation remained in effect, technically allowing any enlisted soldier to don the garment if he chose and if he could acquire it. Surprisingly, some enlisted men wore the double-breasted tunic, albeit privately acquired. While by no means widespread, the garment deserves mention, and a few are shown here that have provenance to the Lower South.

First Sergeant John W. Lester’s uniform provides an excellent example of this type of homemade uniform. Lester, who served with the 10th Georgia Infantry Battalion from Americus, Georgia, had a matching set of double-breasted frock, pants and vest. The jeans cloth is a steel gray color. The coat and pants have black facings. The coat has rows of seven buttons and gold lace chevrons, while the nine-button vest has a fall collar. Lester probably wore the uniform from his enlistment in March 1862 until his death in March 1863 from typhoid fever in Richmond, Virginia.[231] Private Benjamin Taylor Worthington’s broadcloth, seven-button, double-breasted frock, with accompanying vest, provides another example of a regulation uniform worn by an enlisted soldier. Worthington served briefly with the 18th Mississippi Infantry in Virginia before transferring to the 1st Mississippi Cavalry in 1862. Worthington’s regiment fought in the West, where he presumably wore his frock late in the war (assuming this was the last uniform of the war).[232] Sergeant Thomas W. Blandford wore a jean cloth, seven-button, double-breasted frock with black facings, probably as a hospital steward, detailed from the 8th Kentucky Mounted Infantry. The coat is embellished with sixteen small ball buttons and gold braid on each sleeve and has an exterior pocket at the left breast. Blandford’s service record indicates that he was captured in Kentucky on October 14, 1864 and remained in captivity through July 1865, the last few months in a prison hospital. He presumably wore the coat in prison.[233] Sergeant Major Edward D. Robinson’s artillery frock offers an example from South Carolina. Robinson served in Walter’s South Carolina Washington Artillery Company from February 1862 to April 1865, so he probably wore the coat at the end of his service. The coat’s brown jeans closely matches that observed in other South Carolina-made uniforms. Such might suggest that a local manufacturer provided brown jeans for uniforms throughout the war.[234]

First Sergeant John W. Lester’s uniform provides an excellent example of this type of homemade uniform. Lester, who served with the 10th Georgia Infantry Battalion from Americus, Georgia, had a matching set of double-breasted frock, pants and vest. The jeans cloth is a steel gray color. The coat and pants have black facings. The coat has rows of seven buttons and gold lace chevrons, while the nine-button vest has a fall collar. Lester probably wore the uniform from his enlistment in March 1862 until his death in March 1863 from typhoid fever in Richmond, Virginia.[231] Private Benjamin Taylor Worthington’s broadcloth, seven-button, double-breasted frock, with accompanying vest, provides another example of a regulation uniform worn by an enlisted soldier. Worthington served briefly with the 18th Mississippi Infantry in Virginia before transferring to the 1st Mississippi Cavalry in 1862. Worthington’s regiment fought in the West, where he presumably wore his frock late in the war (assuming this was the last uniform of the war).[232] Sergeant Thomas W. Blandford wore a jean cloth, seven-button, double-breasted frock with black facings, probably as a hospital steward, detailed from the 8th Kentucky Mounted Infantry. The coat is embellished with sixteen small ball buttons and gold braid on each sleeve and has an exterior pocket at the left breast. Blandford’s service record indicates that he was captured in Kentucky on October 14, 1864 and remained in captivity through July 1865, the last few months in a prison hospital. He presumably wore the coat in prison.[233] Sergeant Major Edward D. Robinson’s artillery frock offers an example from South Carolina. Robinson served in Walter’s South Carolina Washington Artillery Company from February 1862 to April 1865, so he probably wore the coat at the end of his service. The coat’s brown jeans closely matches that observed in other South Carolina-made uniforms. Such might suggest that a local manufacturer provided brown jeans for uniforms throughout the war.[234]

From start to finish, the Lower South produced ample clothing for its soldiers. The uniforms ranged from standardized types made at the larger operations to obscure examples made by smaller operations. These various types can be gauged by how many survived the war, with more uniforms remaining from the big operations of Atlanta-Columbus, Georgia; Montgomery, Alabama; Columbus, Mississippi; and, the Augusta and Charleston depots. The Lower South holds the distinction of having operated the first, large-scale quartermaster, manufacturing operations in the Confederacy: those in New Orleans and Nashville from the spring of 1861 to the spring of 1862. These manufacturing hubs had phenomenal production for the one year they operated. The depots that followed them in Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama and Mississippi enjoyed equal success and increased their efficiency, uniformity and output towards the end of the war. They did this despite disruptions involved with invading armies, scarcity of resources and a depreciating currency. A Federal soldier made a succinct description of Confederates in November 1862 about how well-clothed they were in an article, “Seven Weeks a Prisoner, and How it Came About, with a History of what I Saw and Experienced in Rebeldom.” Therein, he stated, “The stories we used to hear of the Confederates being badly clothed and fed, and poorly armed, if they ever were true, are true no longer. With the exception of those at Camp Pratt, all I have seen are well clothed in comfortable goods of their own manufacture, and well-armed.”[235] This Yankee’s glowing commendation of Southern manufacturing summed up quite well the success of quartermaster operations in the Lower South.

Continued from Part IV: click here to navigate back to the previous page...

Acknowledgements:

The following institutions and individuals contributed of their time and collections, which has made this part of the Lower South uniform study very meaningful. These include the Library of Congress online database; the University of Alabama collection, Tuscaloosa, Alabama and Librarian Donna Lee Lancaster-Walton; the images of a jacket in a private collection from the prominent conservator Jessica Hack's website; the National Civil War Museum, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; the Richard Ferry collection; Old South Military Antiques and Shannon Pritchard; the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, and Assistant Director of Museum Collections, Nan Prince; Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana and Director Pat Ricci; the Atlanta History Center, Atlanta, Georgia and Dr. Gordon L. Jones, Senior Military Historian and Curator; the Old Court House Museum, Vicksburg, Mississippi and Director George "Bubba" Bolm; the Tennessee State Museum, Nashville, Tennessee and Senior Textiles Curator Candace Adelsohn; the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, and Registrar/Operations Chief Rachel H. Cockrell, and Curator of Education William J. "Joe" Long; the Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina, and Curator of Textiles Jan Hiester; the Don Troiani collection; the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC and the Curator of Armed Forces History Margaret Vining and Curator Patri O'Gan; Stones River National Battlefield, US National Park Service, Murfreesboro, Tennessee; the Joe Fitzgerald collection; the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia and Chief Curator Robert Hancock; the Dr. Michael R. Cunningham collection; and, the Carter House Museum, Franklin, Tennessee.

Copyright: All images in this article are copyrighted to the Adolphus Confederate Uniforms website with the exception of those that are specifically noted as part of the Library of Congress collection, the Smithsonian Institution or the US National Park Service. Those images credited to collections or individuals are nonetheless copyrighted and require permission to publish from those sources.

Bibliography:

[206] The unidentified artillery jacket resides in an unnamed private collection and is known to the author only because the prominent conservator, Jessica Hack, posted images of it on her website. The George Little jacket is part of the University of Alabama collection; CSR Alabama, M311, Roll 61, Sergeant George Little, Company F, 2nd Battalion, Alabama Light Artillery, and CSR Officers, M331, Roll 158, Captain George Little, Ordnance Officer.

[207] The provenance of the Hendy jacket was provided by collector Richard Ferry.

[208] The Hendy jacket is courtesy of Richard Ferry; the CSRs for Hendy were inconclusive, and his service is based upon the story passed down from the family with the jacket.

[209] This artillery jacket is courtesy of Old South Military Antiques, Shannon Pritchard. The jacket is without any available provenance.

[210] Anderson, John Q. (editor), You're listening to a sample of the Audible audio edition.

Learn more Campaigning with Parsons’ Texas Cavalry Brigade, CSA: The War Journals and Letters of the Four Orr Brothers, 12th Texas Cavalry Regiment, Hill Junior College Press, 1967, pp. 118-119, August-September 1863, North Louisiana.

[211] Walter Lord, Editor, The Fremantle Diary: Being the Journal of Lieutenant Colonel James Lyon Arthur Fremantle, Coldstream Guards, on his Three Months in the Southern States, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1954, p. 124: 31 May 1863, General Liddell’s Arkansas Brigade, Shelbyville, Tennessee.

[212] The MaGee coat is courtesy of the MDAH. The author examined the coat on 12 September 2011. CSR Mississippi, M269, Roll 162: there were nine soldiers named Magee in the 7th Mississippi Infantry. The Chalaron sack coat is in the Confederate Memorial Hall collection, author examined the coat on 15 December 2015; CSR Louisiana, M320, Roll 63, 1st Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron, 5th Company, Louisiana Washington Artillery

[213] Uniforms of Archibald Smith and John McNish Hazlehurst are courtesy of the AHC, author examined the uniforms on 23 April 2013; CSR Georgia for both men are inconclusive since they were cadets and not formally enlisted into Confederate service. The service is taken from their family histories and the records at AHC.

[214] The trousers are courtesy of the Old Court House Museum, Vicksburg, Mississippi. The only available provenance at the museum states that they were worn by a cadet at the Georgia Military Institute. The author viewed the artifact on several occasions in its vitrine, the last occasion being in January 2015.

[215] The Oldham jacket is courtesy of the Tennessee State Museum and the Perkins jacket is courtesy of the ACWM. CSR Tennessee, M268, Roll 33, E.R. Oldham, and CSR Tennessee, M268, Roll 48, Captain Thomas F. Perkins. Although Perkins jacket was made for an officer, it has the same characteristics of a homemade enlisted jacket. The Beard jacket is courtesy of the ACWM.

[216] Derbes, Brett J., Prison Productions: Textiles and Other Military Supplies from State Penitentiaries in the Trans-Mississippi Theater during the Civil War, Thesis prepared for the Degree of Master of Arts, University of North Texas, August 2011, p. 30, descriptions of uniforms (see reference, Nathaniel C. Hughes Jr., ed., The Civil War Memoirs of Philip Dangerfield Stephenson, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 1995, p. 18); and, original enlisted frock coat in the Steve Osman collection, author examined the coat ca. January 2007.

[217] Colonel A.C. Myers, Confederate Quartermaster General, to Captain John M. Galt, AQM New Orleans, May 31 and June 5, 1861, Letters and Telegrams Sent, Confederate Quartermaster General’s Office, National Archives, Record Group 109.7.3. Galt’s responses are in Register of Letters Received, Confederate Quartermaster General’s Office, National Archives, Record Group 109.7.3.

[218] The Bomar frock coat is courtesy of the SCCRR collection. The author viewed the coat in its vitrine on 18 May 2016. CSR South Carolina, M267, Roll 343, Robert Hayne Bomar, Company B, 25th South Carolina Infantry, (see also Robert H. Bomar, Company A, Hampton South Carolina Legion, Roll 363).

[219] The Adger frock coat is courtesy of The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina; CSR South Carolina, M267, Roll 343, Captain Joseph E. Adger, Field & Staff, 25th South Carolina Infantry.

[220] The Gibson uniform is courtesy of The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina; the author viewed the uniform in its vitrine on 18 May and 11 November 2016. CSR South Carolina, M267, Roll 69, J.W. Gibson, Company I, 2nd South Carolina Artillery.

[221] The Phillips uniform is courtesy of the Confederate Memorial Hall collection; author viewed the uniform in its vitrine over numerous visits from May 1997 to December 2015; CSR Louisiana, M320, Roll 384, Joseph B. Phillips, Company A, Crescent Regiment, Louisiana Infantry.

[222] The 5th Louisiana frock coat is courtesy of Don Troiani.

[223] The Ryan frock coat is courtesy of the SI, the author viewed the uniform in its vitrine on 10 November 2016; CSR Kentucky, M319, Roll 134, Samuel Blake Ryan (and S.B. Ryan), Company A, 9th Kentucky Mounted Infantry.

[224] The frock coat is courtesy of the Tennessee State Museum, Nashville, Tennessee; CSR Tennessee, M268, Roll 233, Colonel C.H. Williams, Field & Staff, 27th Tennessee Infantry.

[225] The Hall frock coat is courtesy of the Stones River National Battlefield, US National Park Service, Murfreesboro, Tennessee; CSR Kentucky, M319, Roll 99, Henry C. Hall, Company A, 4th Kentucky Mounted Infantry.

[226] The Martin frock coat courtesy of Joe Fitzgerald; author examined the coat on 9 February 2015. CSR Georgia, M266, Roll 208, Thomas J. and Alfred W. Martin, Company E, 6th Georgia Infantry.

[227] The Neely frock coat is courtesy of the ACWM collection. The author has not found Neely’s service records to verify his regimental affiliation or the details of his death.

[228] The Herbst frock coat is courtesy of Dr. Michael R. Cunningham; the author examined the coat on 25 July 2013. CSR Kentucky, M319, Roll 83, Charles Herbst, 2nd Kentucky Mounted Infantry.

[229] Frock coat is courtesy of the Carter House Museum, Franklin, Tennessee; CSR Tennessee, M268, Roll 200, Sergeant James L. Cooper, Company C, 20th Tennessee Infantry (and later, Aide-de-Camp to General Tyler starting July 1864).

[230] The Kelly frock coat is courtesy of the SCCRR collection, author viewed the coat in its vitrine on 18 May and 13 July 2016. CSR South Carolina, M267, Roll 194, Sergeant Thomas N. Kelly, Companies E and H, 5th South Carolina Infantry.

[231] The Lester frock coat is courtesy of the ACWM collection. CSR Georgia, M266, Roll 257, First Sergeant John W. Lester, Companies C and E, 10th Georgia Infantry Battalion.

[232] The Worthington uniform is courtesy of the ACWM collection. CSR Mississippi, M269, Roll 4, B.T. Worthington, Company H, 1st Mississippi Cavalry.

[233] The Blandford frock coat is courtesy of the ACWM collection. CSR Kentucky, M319, Roll 124, Thomas W. Blandford, Companies K and Field & Staff, 8th Kentucky Mounted Infantry.

[234] The Robinson frock coat is courtesy of the Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina; CSR South Carolina M267, Roll 107, Sergeant Major Edward D. Robinson, Captain Walter’s Company, Washington Artillery, South Carolina Light Artillery, first part of the 1st South Carolina Artillery Regiment, and latter assigned to Manly’s Artillery Battalion.

[235] Cincinnati Daily Commercial, December 6, 1862, p. 1, c. 1, Letter from New Orleans, Seven Weeks a Prisoner, and How it Came About, with a History of what I Saw and Experienced in Rebeldom, New Orleans, Louisiana, November 16, 1862.

Continued from Part IV: click here to navigate back to the previous page...

Acknowledgements:

The following institutions and individuals contributed of their time and collections, which has made this part of the Lower South uniform study very meaningful. These include the Library of Congress online database; the University of Alabama collection, Tuscaloosa, Alabama and Librarian Donna Lee Lancaster-Walton; the images of a jacket in a private collection from the prominent conservator Jessica Hack's website; the National Civil War Museum, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; the Richard Ferry collection; Old South Military Antiques and Shannon Pritchard; the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, and Assistant Director of Museum Collections, Nan Prince; Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana and Director Pat Ricci; the Atlanta History Center, Atlanta, Georgia and Dr. Gordon L. Jones, Senior Military Historian and Curator; the Old Court House Museum, Vicksburg, Mississippi and Director George "Bubba" Bolm; the Tennessee State Museum, Nashville, Tennessee and Senior Textiles Curator Candace Adelsohn; the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, and Registrar/Operations Chief Rachel H. Cockrell, and Curator of Education William J. "Joe" Long; the Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina, and Curator of Textiles Jan Hiester; the Don Troiani collection; the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC and the Curator of Armed Forces History Margaret Vining and Curator Patri O'Gan; Stones River National Battlefield, US National Park Service, Murfreesboro, Tennessee; the Joe Fitzgerald collection; the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia and Chief Curator Robert Hancock; the Dr. Michael R. Cunningham collection; and, the Carter House Museum, Franklin, Tennessee.

Copyright: All images in this article are copyrighted to the Adolphus Confederate Uniforms website with the exception of those that are specifically noted as part of the Library of Congress collection, the Smithsonian Institution or the US National Park Service. Those images credited to collections or individuals are nonetheless copyrighted and require permission to publish from those sources.

Bibliography:

[206] The unidentified artillery jacket resides in an unnamed private collection and is known to the author only because the prominent conservator, Jessica Hack, posted images of it on her website. The George Little jacket is part of the University of Alabama collection; CSR Alabama, M311, Roll 61, Sergeant George Little, Company F, 2nd Battalion, Alabama Light Artillery, and CSR Officers, M331, Roll 158, Captain George Little, Ordnance Officer.

[207] The provenance of the Hendy jacket was provided by collector Richard Ferry.

[208] The Hendy jacket is courtesy of Richard Ferry; the CSRs for Hendy were inconclusive, and his service is based upon the story passed down from the family with the jacket.

[209] This artillery jacket is courtesy of Old South Military Antiques, Shannon Pritchard. The jacket is without any available provenance.

[210] Anderson, John Q. (editor), You're listening to a sample of the Audible audio edition.

Learn more Campaigning with Parsons’ Texas Cavalry Brigade, CSA: The War Journals and Letters of the Four Orr Brothers, 12th Texas Cavalry Regiment, Hill Junior College Press, 1967, pp. 118-119, August-September 1863, North Louisiana.

[211] Walter Lord, Editor, The Fremantle Diary: Being the Journal of Lieutenant Colonel James Lyon Arthur Fremantle, Coldstream Guards, on his Three Months in the Southern States, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1954, p. 124: 31 May 1863, General Liddell’s Arkansas Brigade, Shelbyville, Tennessee.

[212] The MaGee coat is courtesy of the MDAH. The author examined the coat on 12 September 2011. CSR Mississippi, M269, Roll 162: there were nine soldiers named Magee in the 7th Mississippi Infantry. The Chalaron sack coat is in the Confederate Memorial Hall collection, author examined the coat on 15 December 2015; CSR Louisiana, M320, Roll 63, 1st Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron, 5th Company, Louisiana Washington Artillery

[213] Uniforms of Archibald Smith and John McNish Hazlehurst are courtesy of the AHC, author examined the uniforms on 23 April 2013; CSR Georgia for both men are inconclusive since they were cadets and not formally enlisted into Confederate service. The service is taken from their family histories and the records at AHC.

[214] The trousers are courtesy of the Old Court House Museum, Vicksburg, Mississippi. The only available provenance at the museum states that they were worn by a cadet at the Georgia Military Institute. The author viewed the artifact on several occasions in its vitrine, the last occasion being in January 2015.

[215] The Oldham jacket is courtesy of the Tennessee State Museum and the Perkins jacket is courtesy of the ACWM. CSR Tennessee, M268, Roll 33, E.R. Oldham, and CSR Tennessee, M268, Roll 48, Captain Thomas F. Perkins. Although Perkins jacket was made for an officer, it has the same characteristics of a homemade enlisted jacket. The Beard jacket is courtesy of the ACWM.

[216] Derbes, Brett J., Prison Productions: Textiles and Other Military Supplies from State Penitentiaries in the Trans-Mississippi Theater during the Civil War, Thesis prepared for the Degree of Master of Arts, University of North Texas, August 2011, p. 30, descriptions of uniforms (see reference, Nathaniel C. Hughes Jr., ed., The Civil War Memoirs of Philip Dangerfield Stephenson, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 1995, p. 18); and, original enlisted frock coat in the Steve Osman collection, author examined the coat ca. January 2007.

[217] Colonel A.C. Myers, Confederate Quartermaster General, to Captain John M. Galt, AQM New Orleans, May 31 and June 5, 1861, Letters and Telegrams Sent, Confederate Quartermaster General’s Office, National Archives, Record Group 109.7.3. Galt’s responses are in Register of Letters Received, Confederate Quartermaster General’s Office, National Archives, Record Group 109.7.3.

[218] The Bomar frock coat is courtesy of the SCCRR collection. The author viewed the coat in its vitrine on 18 May 2016. CSR South Carolina, M267, Roll 343, Robert Hayne Bomar, Company B, 25th South Carolina Infantry, (see also Robert H. Bomar, Company A, Hampton South Carolina Legion, Roll 363).

[219] The Adger frock coat is courtesy of The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina; CSR South Carolina, M267, Roll 343, Captain Joseph E. Adger, Field & Staff, 25th South Carolina Infantry.

[220] The Gibson uniform is courtesy of The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina; the author viewed the uniform in its vitrine on 18 May and 11 November 2016. CSR South Carolina, M267, Roll 69, J.W. Gibson, Company I, 2nd South Carolina Artillery.

[221] The Phillips uniform is courtesy of the Confederate Memorial Hall collection; author viewed the uniform in its vitrine over numerous visits from May 1997 to December 2015; CSR Louisiana, M320, Roll 384, Joseph B. Phillips, Company A, Crescent Regiment, Louisiana Infantry.

[222] The 5th Louisiana frock coat is courtesy of Don Troiani.

[223] The Ryan frock coat is courtesy of the SI, the author viewed the uniform in its vitrine on 10 November 2016; CSR Kentucky, M319, Roll 134, Samuel Blake Ryan (and S.B. Ryan), Company A, 9th Kentucky Mounted Infantry.

[224] The frock coat is courtesy of the Tennessee State Museum, Nashville, Tennessee; CSR Tennessee, M268, Roll 233, Colonel C.H. Williams, Field & Staff, 27th Tennessee Infantry.

[225] The Hall frock coat is courtesy of the Stones River National Battlefield, US National Park Service, Murfreesboro, Tennessee; CSR Kentucky, M319, Roll 99, Henry C. Hall, Company A, 4th Kentucky Mounted Infantry.

[226] The Martin frock coat courtesy of Joe Fitzgerald; author examined the coat on 9 February 2015. CSR Georgia, M266, Roll 208, Thomas J. and Alfred W. Martin, Company E, 6th Georgia Infantry.

[227] The Neely frock coat is courtesy of the ACWM collection. The author has not found Neely’s service records to verify his regimental affiliation or the details of his death.

[228] The Herbst frock coat is courtesy of Dr. Michael R. Cunningham; the author examined the coat on 25 July 2013. CSR Kentucky, M319, Roll 83, Charles Herbst, 2nd Kentucky Mounted Infantry.

[229] Frock coat is courtesy of the Carter House Museum, Franklin, Tennessee; CSR Tennessee, M268, Roll 200, Sergeant James L. Cooper, Company C, 20th Tennessee Infantry (and later, Aide-de-Camp to General Tyler starting July 1864).

[230] The Kelly frock coat is courtesy of the SCCRR collection, author viewed the coat in its vitrine on 18 May and 13 July 2016. CSR South Carolina, M267, Roll 194, Sergeant Thomas N. Kelly, Companies E and H, 5th South Carolina Infantry.

[231] The Lester frock coat is courtesy of the ACWM collection. CSR Georgia, M266, Roll 257, First Sergeant John W. Lester, Companies C and E, 10th Georgia Infantry Battalion.

[232] The Worthington uniform is courtesy of the ACWM collection. CSR Mississippi, M269, Roll 4, B.T. Worthington, Company H, 1st Mississippi Cavalry.

[233] The Blandford frock coat is courtesy of the ACWM collection. CSR Kentucky, M319, Roll 124, Thomas W. Blandford, Companies K and Field & Staff, 8th Kentucky Mounted Infantry.

[234] The Robinson frock coat is courtesy of the Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina; CSR South Carolina M267, Roll 107, Sergeant Major Edward D. Robinson, Captain Walter’s Company, Washington Artillery, South Carolina Light Artillery, first part of the 1st South Carolina Artillery Regiment, and latter assigned to Manly’s Artillery Battalion.

[235] Cincinnati Daily Commercial, December 6, 1862, p. 1, c. 1, Letter from New Orleans, Seven Weeks a Prisoner, and How it Came About, with a History of what I Saw and Experienced in Rebeldom, New Orleans, Louisiana, November 16, 1862.