The South’s White Uniforms

By Fred Adolphus, 21 October 2017

Updated 23 February 2023

In September 1992, I published a short article, entitled Drab: The Forgotten Confederate Color about the Confederate army’s use of white woolen clothing.[1] After twenty-five years, the article has become out-of-date, since so much more information has come to light on the topic. The subject deserves a new article with more reference data and the numerous images of white woolen uniforms that I have acquired over the last twenty-five years. This fresh perspective, along with the many color images, will do justice to this topic and reinforce how prevalent the use of white woolen Confederate uniforms was throughout the war.

Confederate clothing manufacturers used white woolen cloth in every part of the Confederacy, from early to late in the war. Given its universal usage, I have divided this study by region, moving from west to east. Starting in the Trans-Mississippi, I will begin with the products of the Texas State Penitentiary Mill in Huntsville. From the Trans-Mississippi, the study will move eastward.

The Huntsville Mill produced fabrics for the open market before the Civil War. They made three types of cloth: woolen kerseys, cotton “Texas” jeans and cotton osnaburgs. The cotton jeans and osnaburgs were unbleached and undyed, therefore a natural or tannish-white. The woolen kerseys were either left a natural, undyed “sheep’s” gray; left undyed but cleaned for a natural white shade; or, dyed brown.[2] The white woolens and jeans were often used for slave clothing and were commonly associated with work clothing. At the outset of the war, the Huntsville mill became the leading producer of domestic textiles in the Trans-Mississippi region, especially since similar mills in New Orleans, Baton Rouge and Little Rock fell to Federal occupation between April 1862 and September 1863. The Huntsville mill remained the largest producer of textiles in the Trans-Mississippi until the Confederate government established a larger mill at Mound Prairie, Texas in 1864. The Huntsville mill’s importance ensured that white woolen kerseys became a mainstay of Trans-Mississippi Confederate uniforms throughout the war.

Ironically, much of the Huntsville penitentiary’s woolens left the state early in the war. Irby Morgan, on behalf of the Confederate quartermaster in Nashville, Tennessee, contracted for half of the mill’s production for a six-month period, beginning November 1, 1861.[3] The Nashville quartermaster turned the Huntsville goods into uniforms that clothed the army in middle- and western-Tennessee. The mill provided the quartermaster in Tennessee with brown woolens, at least until the end on 1861, at which point the mill ceased dyeing its woolens and made only white kerseys.[4] This is noteworthy because Confederate quartermasters generally demanded gray-dyed woolens (either steel or cadet gray), but the quartermaster department in Tennessee asked for either brown or gray cloth from its suppliers.[5] Numerous accounts both from the quartermasters and troops, as well as neutral observers, describe Confederates in Tennessee, early in the war, as wearing uniforms that were brown in color.[6] Many of these uniforms had been made of Huntsville kerseys. The contract with the Tennessee quartermaster operation was not renewed in May 1862, so that the production could be used in the Trans-Mississippi region.[7]

As of January 1, 1862, the white kerseys were the woolen goods that the Huntsville mill furnished, after the remaining stocks of brown kerseys had been expended. Every depot used Huntsville white woolen kersey and cotton jeans to one degree or another. The Houston and San Antonio Depots received some of the cloth, but it was the Confederate quartermaster operations in Louisiana and Arkansas that received the lion’s share of the Huntsville kerseys and jeans.

The depot at Monroe, Louisiana, which moved to Shreveport in early 1863, got not only Huntsville cloth, but also goods in the form of finished uniforms made by the clothing contractor James P. Spring. Spring acquired materials (osnaburgs, cotton jeans and woolen kerseys) from the Confederate government at Huntsville, and turned the goods into clothing (pants, jackets, shirts and drawers). Judging from his prices, he only charged the government for labor, because the prices do not seem to include the costs for materials. One can infer that Spring must have received the materials at no cost to his operation, but the Confederate government did in fact pay the State of Texas for the goods. In any case, Spring ran his clothing operation in Huntsville. His total invoices to the Confederate quartermaster for jackets and pants, from April 25 to September 30, 1863, included 1,573 White Kersey Jackets at $1.00 each; 1,245 White Kersey Trowsers at $1.00 each; 1,962 Cotton Jeans Jackets at $1.25 each; and, 5,335 Cotton Jeans Pants at $1.25 each. Also included were 294 Great Coats at either $6.00 or $5.00 each, and 88 Overcoats at an unspecified price. The cotton jeans was undyed, natural white, and the great coats were presumably made from the same white kersey that a portion of the jackets and trousers were. All the buttons that Spring used for this production were horn. In total, Spring provided during this period 3,535 jackets (45% white kersey and 55% cotton jeans), and 6,580 pairs of trousers (19% white kersey and 81 % cotton jean). Therefore, most of the uniforms supplied were cotton jeans.[8]

Spring’s invoices do not specify the destination of his uniforms, but when his invoices are compared with the Shreveport Depot’s transfers of the same period, it appears that all of uniforms went to Shreveport. Captain N.A. Birge, Quartermaster at the Shreveport Depot reported transferring the following jackets, pants and overcoats during July and August 1863: 3,065 Jackets; 901 pairs Pants; 24 Jeans Coats; 155 Summer Coats; and, 130 Overcoats. Birge’s transfers of these articles to Captain F.O. Snow, Post Quartermaster for Little Rock, on July 28, 1863, represent a part of the above transfers, but are more specific. Snow received 1,080 Kersey Jackets; 619 pairs Pants; and, 151 Summer Coats. Birge’s kersey jackets, jeans coats and summer coats are presumably the same as Spring’s white kersey jackets and cotton jeans jackets, with the pants and overcoats following suit.[9]

The Confederate clothing depot in Little Rock, Arkansas made clothing from white Huntsville goods, imported blue-gray kersey and from locally made brown and gray woolen-cotton jeans. One of the first, well-documented instances of the Little Rock Depot using Huntsville goods was the period between December 1861 and May 1862. During that time, Major J.F. Minter, Chief Quartermaster for the Trans-Mississippi Department, obtained 35,380 yards of woolens, 12,361 yards cotton jeans and 68,621 yards osnaburgs from the Huntsville penitentiary, enough for 8,000 complete suits of caps, coats, pants, shirts and drawers. Some or all this materiel was sent to Little Rock where it was made into uniforms, and would have been issued to commands from there.[10]

In late 1862, Major John B. Burton, Chief of Clothing Bureau for the Department of the Trans-Mississippi, was still having the Arkansas State Penitentiary in Little Rock manufacture uniforms from Huntsville penitentiary cloth.[11] When Major William H. Haynes replaced Burton in February 1863, he took firmer control over distribution of the Huntsville goods, using them chiefly to supply Confederate troops in Arkansas and Louisiana. Haynes required Captain E.C. Wharton, Chief of Clothing Bureau in Texas, to supply Confederate troops in Texas with imported woolens and Huntsville osnaburgs for the most part.[12]

The major Texas depots by 1863 included Houston and San Antonio, with limited operations in Tyler, Austin, and Brownsville. The Texas depots made almost exclusively cadet gray uniforms from imported blue-gray kerseys, but their stocks were nonetheless occasionally supplemented with Huntsville white kerseys and cotton jeans. Furthermore, Wharton received allotments of Huntsville kerseys and jeans in 1863 to make uniforms for the Texas State Troops that had been called into Confederate service. As a result, the Houston and San Antonio depots made limited quantities of white clothing.

Captain E.C. Wharton mentioned that he used the products of the state penitentiary in his Houston Depot tailor shop: osnaburgs, white plains, white kerseys, and jeans. He received substantial amounts of osnaburgs and cotton jeans, but relative few woolens. The osnaburgs were essential for making shirts, drawers, jacket and trouser linings, and other articles such as haversacks, and corn sacks. The cotton jeans were likewise critical elements in Wharton’s production of such articles as tents and flies, wagon covers, listers, haversacks and knapsacks. Due to the greater need for the aforementioned articles, Wharton used cotton jeans sparing for clothing. Nevertheless, he did manufacture some trousers, over shirts, drawers and linings (for jackets and trousers) from cotton jeans, when he had enough to spare for clothing items.[13] Wharton’s expenditure report for November 1863 illustrates his frugal use of cotton jeans for clothing as he reported using cotton jeans for lining a small proportion of the jackets and most of the trousers that he made; and for making 392 shirts and 2,120 pairs of drawers. The cotton jeans were undyed, white.[14]

While Wharton does not explicitly state that the cotton jeans constituted a “summer uniform,” this conclusion can be inferred because he does state that his cadet gray woolen jackets and trousers, and light blue woolen trousers made up his winter uniform. In two reports from October and December 1863 at the Houston Depot, Wharton makes a clear distinction between summer and winter jackets and trousers. In his October inventory, he reported 711 summer and 957 winter jackets (42% summer jackets), and 2,657 pair of summer trousers and 3,347 pair of winter trousers (44% summer trousers).[15] He reported stocks in December of 500 summer jackets, 1,051 winter jackets, 2,527 pairs summer trousers and 4,637 pairs winter trousers.[16] These inventories suggest that Wharton made white uniforms (cotton jeans jackets and pants) whenever he had enough of the material to do so.

Wharton occasionally made white kersey clothing, but this was limited due to preferential allocation to Shreveport and Little Rock. He reported in his expenditures for November 1863 that he had made 60 pairs of white kersey trousers, compared with 2,193 pairs of cadet gray and 290 pairs of light blue woolen trousers. In October, he had also received enough penitentiary kerseys to make 2,000 jackets and trousers, which would “answer either for the Troops, or the Negroes [of the Labor Bureau], as the Major General may direct.”[17]

Wharton had a keen interest in obtaining white kerseys from Huntsville in 1863 to supply the Labor Bureau negroes of the Engineer Department and the Texas State Troops. Major Haynes, however, was not providing Wharton’s operation with enough woolens. Of the Labor Bureau negroes’ clothing, Wharton stated, “The goods from the Texas State Penitentiary (Osnaburgs, Jeans, Plains & Kerseys) are alone suitable for the purpose; and the only over at prices that will not eat up what the Planter receives in pay from the Govt, for his Negroes services. These goods, however, are under the control of Maj. Haynes, Chf of Clothing, Dept. Trans Misspi; and as the Penitentiary cannot supply enough Material for the wants of the Army, it will be hard to divert to Negroes what the Troops must have.”[18] Wharton was further frustrated by the fact that the negroes’ owners paid the Confederate government directly for the clothing their slaves received instead of giving the money to the clothing bureau that had provided the clothing.[19] Regardless, Wharton issued 1,201 jackets and 1,423 pairs of trousers to the Labor Bureau negroes in 1863, and these suits were probably all white kersey or white cotton jeans.[20]

Wharton was also involved with clothing to the Texas State Troops, who had been called to active service twice in 1863. The Confederate quartermaster was required to pay the State of Texas for the Huntsville goods (cottons jeans, osnaburgs, white kerseys), as well as buttons and thread, required to make their uniforms, since the troops came under Confederate command. The Texas State Troop Chief Quartermaster, Captain E.W. Taylor, had the materials made into clothing.[21] Each state troop was to receive a suit consisting of a jacket, trousers, shirt and drawers. The jackets, trousers and shirts were to be made with five buttons each, and the drawers with two (probably following the pattern of the Houston uniforms).[22] Taylor’s records indicate that he received both woolen kerseys and cotton jeans, and he could have made both woolen and cotton uniforms. The state troops also received some Confederate clothing from Captain Wharton, as well.[23]

The San Antonio Depot also issued limited quantities of white uniforms. These were presumably made of Huntville white kerseys, and are described in clothing rolls and transfers as “Blouses, White Woolen” and “Trousers, White Woolen.” The 3rd Texas Volunteer Infantry received these suits from the San Antonio quartermaster from November 1862 through March 1863.[24] The Houston Depot issued the 3rd Texas more “White Woolen Trousers” and “Blouses” (probably white woolen, as well) at Sabine City, Texas, in August 1863, as well as a quantity of “White Linnen Trousers.”[25] The latter were probably Huntsville, cotton jeans trousers. The 2nd Texas Field Battery received the same uniforms from San Antonio, described as “white woolen blowses and trowsers,” on November 10 and December 2, 1862.[26] The distribution of white uniforms was more widespread than just these two commands, but exact descriptions in other transfer documents do not use the word “white” or “linen” in their descriptions. Many white uniforms were issued under non-specific descriptions such as “blouses,” “jackets,” and “trousers” which precludes using them as examples for this study.

Confederate clothing manufacturers used white woolen cloth in every part of the Confederacy, from early to late in the war. Given its universal usage, I have divided this study by region, moving from west to east. Starting in the Trans-Mississippi, I will begin with the products of the Texas State Penitentiary Mill in Huntsville. From the Trans-Mississippi, the study will move eastward.

The Huntsville Mill produced fabrics for the open market before the Civil War. They made three types of cloth: woolen kerseys, cotton “Texas” jeans and cotton osnaburgs. The cotton jeans and osnaburgs were unbleached and undyed, therefore a natural or tannish-white. The woolen kerseys were either left a natural, undyed “sheep’s” gray; left undyed but cleaned for a natural white shade; or, dyed brown.[2] The white woolens and jeans were often used for slave clothing and were commonly associated with work clothing. At the outset of the war, the Huntsville mill became the leading producer of domestic textiles in the Trans-Mississippi region, especially since similar mills in New Orleans, Baton Rouge and Little Rock fell to Federal occupation between April 1862 and September 1863. The Huntsville mill remained the largest producer of textiles in the Trans-Mississippi until the Confederate government established a larger mill at Mound Prairie, Texas in 1864. The Huntsville mill’s importance ensured that white woolen kerseys became a mainstay of Trans-Mississippi Confederate uniforms throughout the war.

Ironically, much of the Huntsville penitentiary’s woolens left the state early in the war. Irby Morgan, on behalf of the Confederate quartermaster in Nashville, Tennessee, contracted for half of the mill’s production for a six-month period, beginning November 1, 1861.[3] The Nashville quartermaster turned the Huntsville goods into uniforms that clothed the army in middle- and western-Tennessee. The mill provided the quartermaster in Tennessee with brown woolens, at least until the end on 1861, at which point the mill ceased dyeing its woolens and made only white kerseys.[4] This is noteworthy because Confederate quartermasters generally demanded gray-dyed woolens (either steel or cadet gray), but the quartermaster department in Tennessee asked for either brown or gray cloth from its suppliers.[5] Numerous accounts both from the quartermasters and troops, as well as neutral observers, describe Confederates in Tennessee, early in the war, as wearing uniforms that were brown in color.[6] Many of these uniforms had been made of Huntsville kerseys. The contract with the Tennessee quartermaster operation was not renewed in May 1862, so that the production could be used in the Trans-Mississippi region.[7]

As of January 1, 1862, the white kerseys were the woolen goods that the Huntsville mill furnished, after the remaining stocks of brown kerseys had been expended. Every depot used Huntsville white woolen kersey and cotton jeans to one degree or another. The Houston and San Antonio Depots received some of the cloth, but it was the Confederate quartermaster operations in Louisiana and Arkansas that received the lion’s share of the Huntsville kerseys and jeans.

The depot at Monroe, Louisiana, which moved to Shreveport in early 1863, got not only Huntsville cloth, but also goods in the form of finished uniforms made by the clothing contractor James P. Spring. Spring acquired materials (osnaburgs, cotton jeans and woolen kerseys) from the Confederate government at Huntsville, and turned the goods into clothing (pants, jackets, shirts and drawers). Judging from his prices, he only charged the government for labor, because the prices do not seem to include the costs for materials. One can infer that Spring must have received the materials at no cost to his operation, but the Confederate government did in fact pay the State of Texas for the goods. In any case, Spring ran his clothing operation in Huntsville. His total invoices to the Confederate quartermaster for jackets and pants, from April 25 to September 30, 1863, included 1,573 White Kersey Jackets at $1.00 each; 1,245 White Kersey Trowsers at $1.00 each; 1,962 Cotton Jeans Jackets at $1.25 each; and, 5,335 Cotton Jeans Pants at $1.25 each. Also included were 294 Great Coats at either $6.00 or $5.00 each, and 88 Overcoats at an unspecified price. The cotton jeans was undyed, natural white, and the great coats were presumably made from the same white kersey that a portion of the jackets and trousers were. All the buttons that Spring used for this production were horn. In total, Spring provided during this period 3,535 jackets (45% white kersey and 55% cotton jeans), and 6,580 pairs of trousers (19% white kersey and 81 % cotton jean). Therefore, most of the uniforms supplied were cotton jeans.[8]

Spring’s invoices do not specify the destination of his uniforms, but when his invoices are compared with the Shreveport Depot’s transfers of the same period, it appears that all of uniforms went to Shreveport. Captain N.A. Birge, Quartermaster at the Shreveport Depot reported transferring the following jackets, pants and overcoats during July and August 1863: 3,065 Jackets; 901 pairs Pants; 24 Jeans Coats; 155 Summer Coats; and, 130 Overcoats. Birge’s transfers of these articles to Captain F.O. Snow, Post Quartermaster for Little Rock, on July 28, 1863, represent a part of the above transfers, but are more specific. Snow received 1,080 Kersey Jackets; 619 pairs Pants; and, 151 Summer Coats. Birge’s kersey jackets, jeans coats and summer coats are presumably the same as Spring’s white kersey jackets and cotton jeans jackets, with the pants and overcoats following suit.[9]

The Confederate clothing depot in Little Rock, Arkansas made clothing from white Huntsville goods, imported blue-gray kersey and from locally made brown and gray woolen-cotton jeans. One of the first, well-documented instances of the Little Rock Depot using Huntsville goods was the period between December 1861 and May 1862. During that time, Major J.F. Minter, Chief Quartermaster for the Trans-Mississippi Department, obtained 35,380 yards of woolens, 12,361 yards cotton jeans and 68,621 yards osnaburgs from the Huntsville penitentiary, enough for 8,000 complete suits of caps, coats, pants, shirts and drawers. Some or all this materiel was sent to Little Rock where it was made into uniforms, and would have been issued to commands from there.[10]

In late 1862, Major John B. Burton, Chief of Clothing Bureau for the Department of the Trans-Mississippi, was still having the Arkansas State Penitentiary in Little Rock manufacture uniforms from Huntsville penitentiary cloth.[11] When Major William H. Haynes replaced Burton in February 1863, he took firmer control over distribution of the Huntsville goods, using them chiefly to supply Confederate troops in Arkansas and Louisiana. Haynes required Captain E.C. Wharton, Chief of Clothing Bureau in Texas, to supply Confederate troops in Texas with imported woolens and Huntsville osnaburgs for the most part.[12]

The major Texas depots by 1863 included Houston and San Antonio, with limited operations in Tyler, Austin, and Brownsville. The Texas depots made almost exclusively cadet gray uniforms from imported blue-gray kerseys, but their stocks were nonetheless occasionally supplemented with Huntsville white kerseys and cotton jeans. Furthermore, Wharton received allotments of Huntsville kerseys and jeans in 1863 to make uniforms for the Texas State Troops that had been called into Confederate service. As a result, the Houston and San Antonio depots made limited quantities of white clothing.

Captain E.C. Wharton mentioned that he used the products of the state penitentiary in his Houston Depot tailor shop: osnaburgs, white plains, white kerseys, and jeans. He received substantial amounts of osnaburgs and cotton jeans, but relative few woolens. The osnaburgs were essential for making shirts, drawers, jacket and trouser linings, and other articles such as haversacks, and corn sacks. The cotton jeans were likewise critical elements in Wharton’s production of such articles as tents and flies, wagon covers, listers, haversacks and knapsacks. Due to the greater need for the aforementioned articles, Wharton used cotton jeans sparing for clothing. Nevertheless, he did manufacture some trousers, over shirts, drawers and linings (for jackets and trousers) from cotton jeans, when he had enough to spare for clothing items.[13] Wharton’s expenditure report for November 1863 illustrates his frugal use of cotton jeans for clothing as he reported using cotton jeans for lining a small proportion of the jackets and most of the trousers that he made; and for making 392 shirts and 2,120 pairs of drawers. The cotton jeans were undyed, white.[14]

While Wharton does not explicitly state that the cotton jeans constituted a “summer uniform,” this conclusion can be inferred because he does state that his cadet gray woolen jackets and trousers, and light blue woolen trousers made up his winter uniform. In two reports from October and December 1863 at the Houston Depot, Wharton makes a clear distinction between summer and winter jackets and trousers. In his October inventory, he reported 711 summer and 957 winter jackets (42% summer jackets), and 2,657 pair of summer trousers and 3,347 pair of winter trousers (44% summer trousers).[15] He reported stocks in December of 500 summer jackets, 1,051 winter jackets, 2,527 pairs summer trousers and 4,637 pairs winter trousers.[16] These inventories suggest that Wharton made white uniforms (cotton jeans jackets and pants) whenever he had enough of the material to do so.

Wharton occasionally made white kersey clothing, but this was limited due to preferential allocation to Shreveport and Little Rock. He reported in his expenditures for November 1863 that he had made 60 pairs of white kersey trousers, compared with 2,193 pairs of cadet gray and 290 pairs of light blue woolen trousers. In October, he had also received enough penitentiary kerseys to make 2,000 jackets and trousers, which would “answer either for the Troops, or the Negroes [of the Labor Bureau], as the Major General may direct.”[17]

Wharton had a keen interest in obtaining white kerseys from Huntsville in 1863 to supply the Labor Bureau negroes of the Engineer Department and the Texas State Troops. Major Haynes, however, was not providing Wharton’s operation with enough woolens. Of the Labor Bureau negroes’ clothing, Wharton stated, “The goods from the Texas State Penitentiary (Osnaburgs, Jeans, Plains & Kerseys) are alone suitable for the purpose; and the only over at prices that will not eat up what the Planter receives in pay from the Govt, for his Negroes services. These goods, however, are under the control of Maj. Haynes, Chf of Clothing, Dept. Trans Misspi; and as the Penitentiary cannot supply enough Material for the wants of the Army, it will be hard to divert to Negroes what the Troops must have.”[18] Wharton was further frustrated by the fact that the negroes’ owners paid the Confederate government directly for the clothing their slaves received instead of giving the money to the clothing bureau that had provided the clothing.[19] Regardless, Wharton issued 1,201 jackets and 1,423 pairs of trousers to the Labor Bureau negroes in 1863, and these suits were probably all white kersey or white cotton jeans.[20]

Wharton was also involved with clothing to the Texas State Troops, who had been called to active service twice in 1863. The Confederate quartermaster was required to pay the State of Texas for the Huntsville goods (cottons jeans, osnaburgs, white kerseys), as well as buttons and thread, required to make their uniforms, since the troops came under Confederate command. The Texas State Troop Chief Quartermaster, Captain E.W. Taylor, had the materials made into clothing.[21] Each state troop was to receive a suit consisting of a jacket, trousers, shirt and drawers. The jackets, trousers and shirts were to be made with five buttons each, and the drawers with two (probably following the pattern of the Houston uniforms).[22] Taylor’s records indicate that he received both woolen kerseys and cotton jeans, and he could have made both woolen and cotton uniforms. The state troops also received some Confederate clothing from Captain Wharton, as well.[23]

The San Antonio Depot also issued limited quantities of white uniforms. These were presumably made of Huntville white kerseys, and are described in clothing rolls and transfers as “Blouses, White Woolen” and “Trousers, White Woolen.” The 3rd Texas Volunteer Infantry received these suits from the San Antonio quartermaster from November 1862 through March 1863.[24] The Houston Depot issued the 3rd Texas more “White Woolen Trousers” and “Blouses” (probably white woolen, as well) at Sabine City, Texas, in August 1863, as well as a quantity of “White Linnen Trousers.”[25] The latter were probably Huntsville, cotton jeans trousers. The 2nd Texas Field Battery received the same uniforms from San Antonio, described as “white woolen blowses and trowsers,” on November 10 and December 2, 1862.[26] The distribution of white uniforms was more widespread than just these two commands, but exact descriptions in other transfer documents do not use the word “white” or “linen” in their descriptions. Many white uniforms were issued under non-specific descriptions such as “blouses,” “jackets,” and “trousers” which precludes using them as examples for this study.

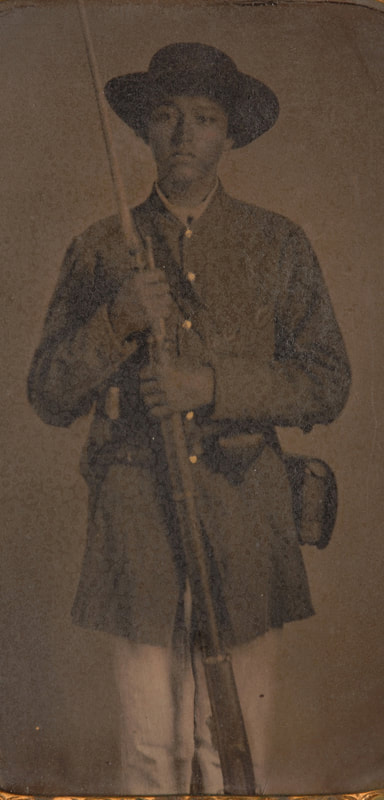

Image 2: Unidentified soldier, believed have served in a Texas Regiment. The only available provenance is that image is from a Mexican-heritage family in Houston, Texas. The soldier wears a pair of white cotton jeans cloth or white kersey trousers with his apparently gray frock coat. The Confederate quartermaster issued such pants to troops in Texas. This image has been inverted to make the coat appear correct. The soldier switched his accoutrements to the left side due to the mirror image effect of the original. Image courtesy of the David Wynn Vaughan collection.

The State of Texas had its own quartermaster operation called the State Military Board. This agency provided modest amounts of domestic and imported clothing to the state military. This force consisted of the Texas State Troops, subject to being called out as troops-of-the-line in Confederate service, and the Frontier Regiment: a standing body of mounted rangers. The Frontier Regiment was raised to fight Comanches along the line of settlement. This regiment served under the state from 1862 until 1864, when it was transferred into Confederate service. It remained on the frontier, however, throughout the war. The Confederate quartermaster was responsible for clothing the Texas State Troops, but the state had to clothe the Frontier Regiment.

The state issued uniforms, made from Huntsville goods, to the Frontier Regiment in 1863. During the first quarter of the year, the state quartermaster manufactured for the regiment: 2,218 pairs of pants, 1,231 coats, 1,179 jackets, 3,491 shirts and 1,659 pairs of drawers. Of this, the regiment drew: 1,620 pairs of pants, 841 coats, 837 jackets, 2,510 shirts and 1,213 pairs of drawers, leaving the balance with the quartermaster. The pants, coats and jackets were made of white kersey and lined with osnaburgs, while the shirts and drawers were made of osnaburgs. No description remains of the buttons used, and not mention was made of having used pant buckles.[27]

The regiment requisitioned cotton jeans and osnaburgs on July 17, 1863 to make 300 coats, 1,000 jackets, 2,000 pairs of pants, 3,000 shirts and 2,000 pairs of drawers. Each coat called for six yards of jeans and two and a half yards of osnaburgs for linings; the jackets required three yards of jeans and two of osnaburgs; and, the pants stated only three yards of jeans were required. The drawers took two and three quarters yards of osnaburgs to make, while the shirts required three yards of osnaburgs each. No mention is made of buttons or pant buckles. What the requisition makes clear, considering how much fabric is required for garment, is that the Huntsville goods were single width, and it took twice as many yards to make each garment as it did with double width fabrics. Jackets were intended for the enlisted troops, and double-breasted frock coats for the officers and sergeants.[28]

The last Frontier Regiment clothing records date from December 1863 to February 1864. During that winter, the regiment was issued clothing and clothing materials (perhaps from the July requisition). The ready-made clothing included “Cavalry Jackets,” pants, over shirts, undershirts, drawers and shoes. Some of the shirts were described as flannel. The cavalry jackets may have been so designated because they had yellow facings, but this is just a guess. The quartermaster issued clothing materials that consisted of cotton jeans and osnaburgs. Cotton jeans was issued out at the rate of six yards per man for coats, along with six yards of osnaburgs for linings, and three yards of jeans per man for pants, along with a half yard of osnaburgs for linings. The cloth was also issued with thread and five buttons (the buttons were probably intended for the pants). Furthermore, some men drew more buttons: some a dozen, and others one and half dozen, making it difficult say how many may have been used for the coat.[29] In any case, all the uniforms were undyed, white, Huntsville cotton jeans.

Moving east, across the Mississippi River into the Lower South, we find much evidence the use of white woolen uniforms. The Confederate quartermaster in Nashville, Tennessee offered premium prices in August and September 1861 for “heavy grey jeans and thick white linsey.”[30] During the same period, the manufacturing city of New Orleans provided an early reference to white uniforms. One of the city’s largest manufacturers of Confederate clothing, Hebrard & Co., made both elaborate and simple uniforms for the Confederate quartermaster. Hebrard’s more elaborate uniforms included “Artillery Uniform Coats and Pants,” and “Infantry Uniform Coats and Pants,” priced at $7.75 each ($5.25 for the coat and $2.50 for the pants). Hebrard made these between February and June 1861, and each suit came with two flannel shirts and two pairs of cotton drawers. By the August-September timeframe, Hebrard had apparently ceased supplying the branch-specific uniforms, and switched to simpler clothing. During that time, he supplied 5,000 suits of “White Kentucky Jeans,” and 300 suits of “Gray Kentucky Jeans” (both at $5.50 per suit); and, 225 suits of “Gray Kersey” at $3.50 per suit.[31] Hebrard’s production of undyed, natural white uniforms reflected a need for quickly-made, mass-produced clothing that was simple, practical and cheap. Doubtless, the Confederate quartermaster was unwilling to pay for expensive, embellished, time-consuming soldier suits. Other New Orleans clothing manufacturers did the same as Hebrard and made simpler uniforms, as well. The New Orleans factories continued to supply the Confederate quartermaster until the Federals occupied the area in April 1862.

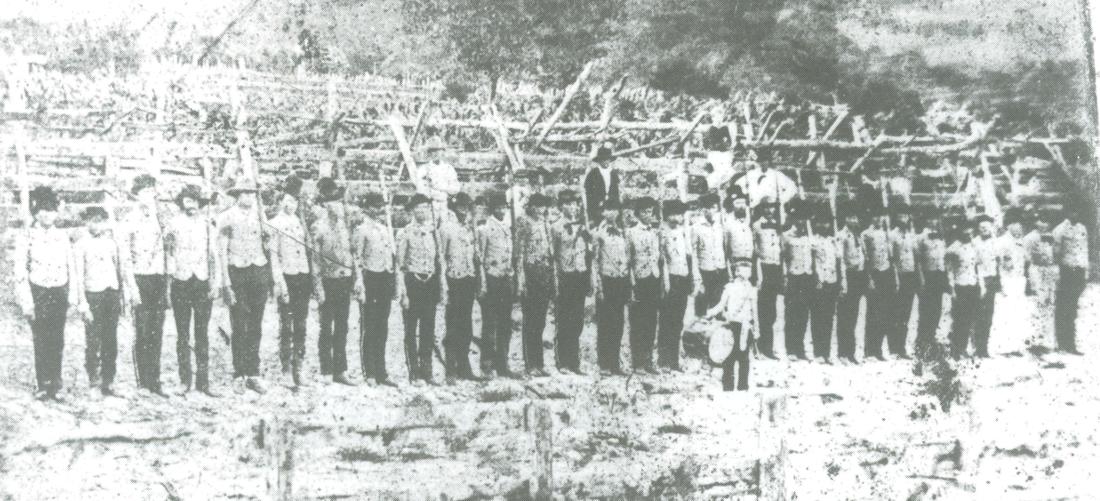

Perhaps the most well-known issues of Hebrard uniforms was to the Missouri troops in Northwest Arkansas in early 1862. These were delivered to General Ben McCulloch’s army in the Boston Mountains, and were allotted to the First Missouri Brigade. The clothing included part or all of two shipments of 5,000 white Kentucky jeans suits and osnaburg shirts.[32] Ephraim Anderson of the 2nd Missouri Infantry Regiment recalled when his command received them on March 1-2, “Our regiment was uniformed here; the cloth was of rough and coarse texture, and the cutting and style would have produced a sensation in fashionable circles: the stuff was white, never having been colored, with a goodly supply of grease – the wool had not been purified by any application of water since it was taken from the back of the sheep. In pulling off and putting on the clothes, the olfactories were constantly exercised with a strong odor of that animal.

“Our brigade was the only body of troops that had these uniforms issued to them, and were often greeted with a chorus of ba-a-as… Our clothes, however, were strong and serviceable, if we did look and feel somewhat sheepish in them.”

This issue of clothing was also described by James Harding, the Quartermaster General for the Missouri troops. Harding distributed uniforms and accouterments to Burbridge’s 2nd Missouri Infantry, and, in part, to Rives’ 3rd Missouri Infantry. The issue was made in the Missouri camp at Cove Creek, Arkansas, probably in late February 1862. Harding reported, “Advantage was taken… to issue to the troops the clothing, blankets, etc., which had been so long in the wagons, and which there was great need… the jackets and pants were of white linsey, with big wooden buttons, with which Rives and Burbridge’s regiments were furnished… These clothes were real nigger clothing, but were warm, of good material, were uniform in color, and far preferable to no clothes at all. The black belts and equipments set of [sic] the linsey very nicely, and the regiment looked really well in their working clothes.”[33]

Another famous story about the mass-produced, white, New Orleans-made uniforms comes from the 2nd Texas Infantry Regiment. The regiment’s commander, Colonel J.W. Moore, had sent a requisition for gray uniforms to the Confederate quartermaster at New Orleans prior to his regiment departing Houston, Texas on March 18, 1862. The cloth used to make these uniforms was from one of Irby Morgan’s last consignments of Huntsville goods to the Nashville quartermaster. Since Nashville had fallen, Morgan had the cloth sent to New Orleans. Morgan had promised to make the 2nd Texas Infantry Regiment’s uniforms from these woolens.[34] When the regiment arrived in Corinth, Mississippi, on April 1, 1862, and Moore recalled:

“When my regiment, the Second Texas Infantry, was organized, at Galveston in 1861, not being able to procure Confederate gray, the men were supplied with Federal blue uniforms captured at Texas military posts. When, in March, 1862, we were ordered to report to Gen. A.S. Johnston, then at Corinth, we marched across the country to Alexandria, and thence were conveyed by steamer and railroad to our destination.

“Not believing Federal blue a life prolonging color for a Confederate uniform in battle, I sent an agent with a requisition on the quartermaster at New Orleans for properly colored uniforms. He met us at Corinth a few days before marching for the Shiloh (or Pittsburg Landing) battlefield. When the packages were opened, we found the so-called uniforms as white as washed wool could make them. I shall never forget the men’s consternation and many exclamations not quoted in the Bible, such as, “Well, I’ll be d-----!,” “Don’t them things beat h---!,” “Do the generals expect us to be killed, and want us to wear our shrouds?,” etc. Being a case of Hobson’s choice, the men cheerfully made the best of the situation, quickly stripped off the ragged blue and donned the virgin white. The clothing having no marks as to sizes, articles were issued just as they came, hit or miss as to fit. Soon the company grounds were full of men strutting up and down, some with trousers dragging under their heels, while those of others scarcely reached the tops of their socks; some with jackets so tight they resembled stuffed toads, while others had ample room to carry three days’ rations in their bosoms. The exhibition closed with a swapping scene that reminded one of a horse-trading day in a Georgia country town. A Federal prisoner at Shiloh inquired: “Who were them hell-cats that went into battle dressed in their graveclothes?”[35]

Significantly, the white woolen uniforms represented a trend in manufacturing. The Confederate factories in Mississippi would produce, and the Army of Mississippi would wear white woolen uniforms for much of the war. Additionally, the Texans’ uniform consignment was one of the last to leave New Orleans for the Confederate army, and it highlights how important the city was in supplying clothing to the Confederacy.

At least one factory in Mississippi left a record of having made white cloth for the Confederate quartermaster, although there may have been more. James M. Wesson’s Mississippi Manufacturing Company at Bankston furnished woolen linseys and jeans to the quartermaster from late 1861 to at least August 1863. In September 1862, Wesson sold “W Jeans,” “Bro Jeans,” and “W Linseys” to the Confederate quartermaster at Jackson. The abbreviations probably stand for “white” and “brown.” He also furnished jackets to the Selma quartermaster in 1863, that were described as “linsey,” and could have been white linsey.[36]

There are both written accounts and surviving artifacts that document the use of white uniforms in Mississippi. Willie H. Tunnard of the 3rd Louisiana Infantry wrote that his command received the white uniforms at Snydor’s Mill, in mid-March 1863, prior to March 22nd. Tunnard recounted the event: “The regiment received a new uniform, which they were ordered to take, much against their expressed wishes. The material was a very coarse white jeans, ‘Nolen Volens.’ The uniforms were issued to the men, few of whom would wear them, unless under compulsion, by some special order. On March 22nd orders were issued to cook three days’ rations, and be prepared to move ere daylight the succeeding morning. The weather was gloomy and rainy, the roads in a terrible condition. Some of the men suggested the propriety of wearing the new white uniforms on the approaching expedition, which, it was known, would be among the swamps of the Yazoo Valley. The suggestion was almost universally adopted, affording a rare opportunity to give the new clothes a thorough initiation into the mysteries of a soldier’s life. Thus the regiment assembled the next morning arrayed as if for a summer’s day festival.”[37]

The 26th Louisiana Infantry Regiment received the same type of white uniform that March, as well. The 26th Louisiana had similar misgivings about the new uniforms. Their regimental commander, Colonel Winchester Hall, recorded that,

“About this time [March 1863] we received at Vicksburg the fruits of the conscript levees in Louisiana. The men so raised were placed in various Louisiana commands, after receiving a white woolen uniform. The uniform was unlike any other about us, and marked these men among the volunteer soldiers, who treated them with a contempt, in many cases, undeserved; but so it was the white uniform was known only as an emblem of reproach wherever it appeared.

“Soon after these men were in harness, our regiment received the same kind of uniform; now the Quarter Master's Department of the 26th was never so plethoric as to supply our mere necessities in this line, and a suit of clothes all around was a rare occasion. The clothing was sorely needed, but a howl of indignation rose from the regiment, at the bare suggestion of wearing the badge of a conscript. The indignation was intensified by the fact that none of the conscripts had been put into the ranks of the 26th, and its integrity as a volunteer organization was intact.

“Comfort, appearance, everything was forgotten in the thought that henceforth men who had sought the ranks, and men who had been impressed into service, would be blended, by the uniform, into an undistinguishable mass. The indignation seemed so becoming a volunteer, that officers were loath to invoke the coercive measures in their power. They appealed to the men, and showed the folly of giving away to a fancy. One company after another, in time, yielded to what appeared to be inevitable, until Company B — staunch old hearts — stood out alone. Captain Bateman, however, never relaxed his efforts to kindly bring them to a sense of duty, until only two of the company stood out. The Captain reported the case to me. I ordered the men to be tied up by the thumbs until they were disposed to obey the orders of their Captain. They soon relented, but I fear not willingly.”[38]

By the time of the battles around Vicksburg, the white uniform seems to have been commonplace among the Confederate troops in Mississippi. Lieutenant Anthony B. Burton of the 5th Ohio Battery reported that Cummings’ Georgia Brigade was clothed in undyed wool uniforms at the siege of Vicksburg.[39]

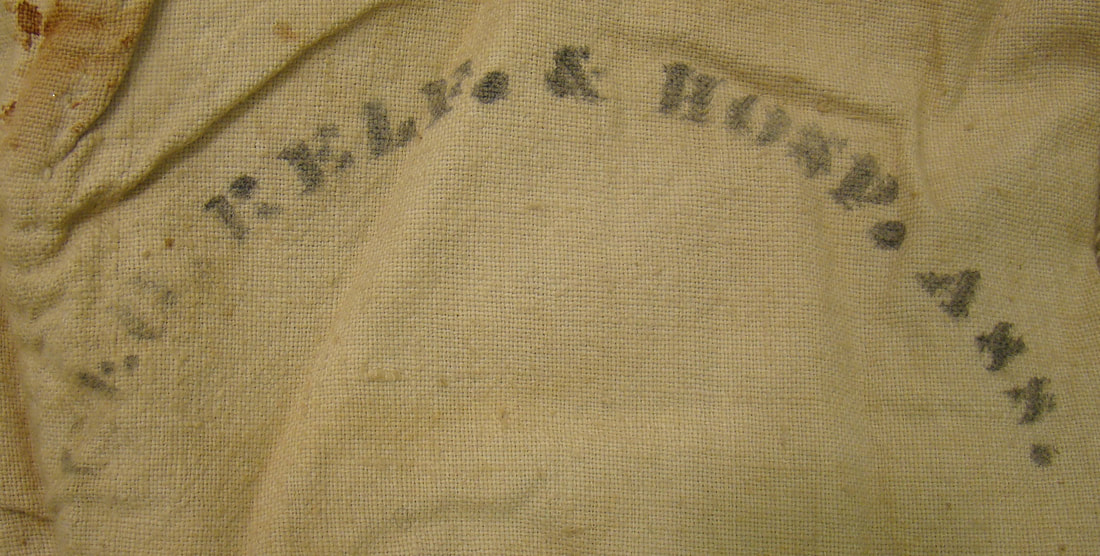

The first concrete example of depot-issued white Confederate clothing pants, presented herein, is the uniform worn by John Thomas Appler, Company H, 1st Missouri Infantry, in Mississippi, May 1863. The uniform is significant because it represents not only a relatively early war example, but also, it is the only surviving white woolen uniform of the Army of Mississippi, a uniform type that was common during the campaigns for Vicksburg in 1862 and 1863. The uniform consists of a jacket and pair of trousers.[40]

Appler was wounded at Champion Hill when a ball went completely through his left ankle. He was left on the field when the Confederate army retreated, and taken prisoner. Soon thereafter, he was released and sent to Confederate lines where he received care at the hospitals in Jackson, Mississippi, and Mobile, Alabama. Due to his debilitating wound, he was furloughed in October and went home to Hannibal, Missouri. There, he was captured, sent to a Federal hospital and eventually paroled March 8, 1864, at which time his military service effectively ended.[41]

Regarding the provenance of his uniform, he may have worn it at the Champion Hill, but there is a better chance that he got the uniform when he was in the 1st Mississippi CSA Hospital in Jackson. The latter possibility makes sense, because the pants do not show signs of a bullet hole or blood stains. Furthermore, Appler would likely have gotten clean, new clothing when he went to the hospital. He may also have gotten only a new pair of pants to place the blood-stained, damaged ones, and kept his old jacket. Not that this has any bearing upon the origins of his uniform. Whether he got it before Champion Hill or in the Hospital afterwards, the uniform still came from a Confederate factory in Mississippi, and still represents the white woolen type so common to the Army of Mississippi.

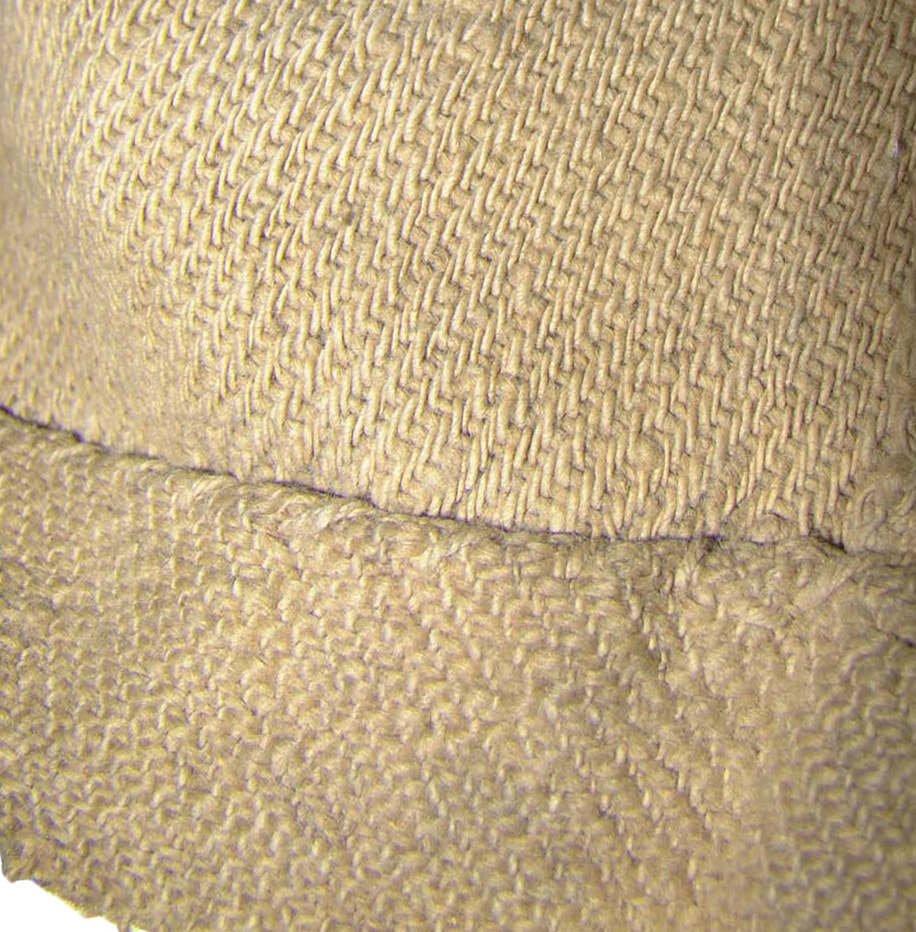

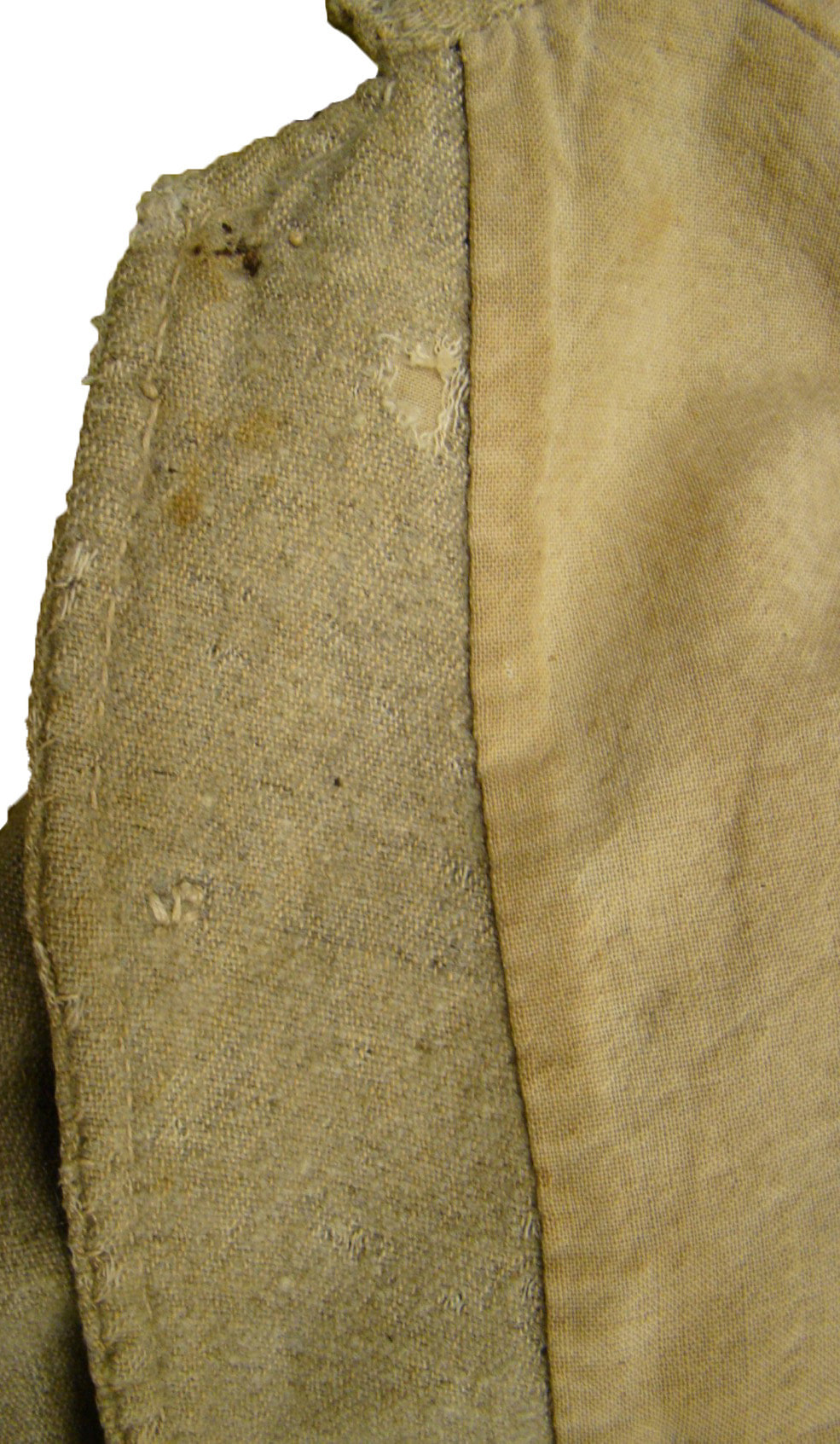

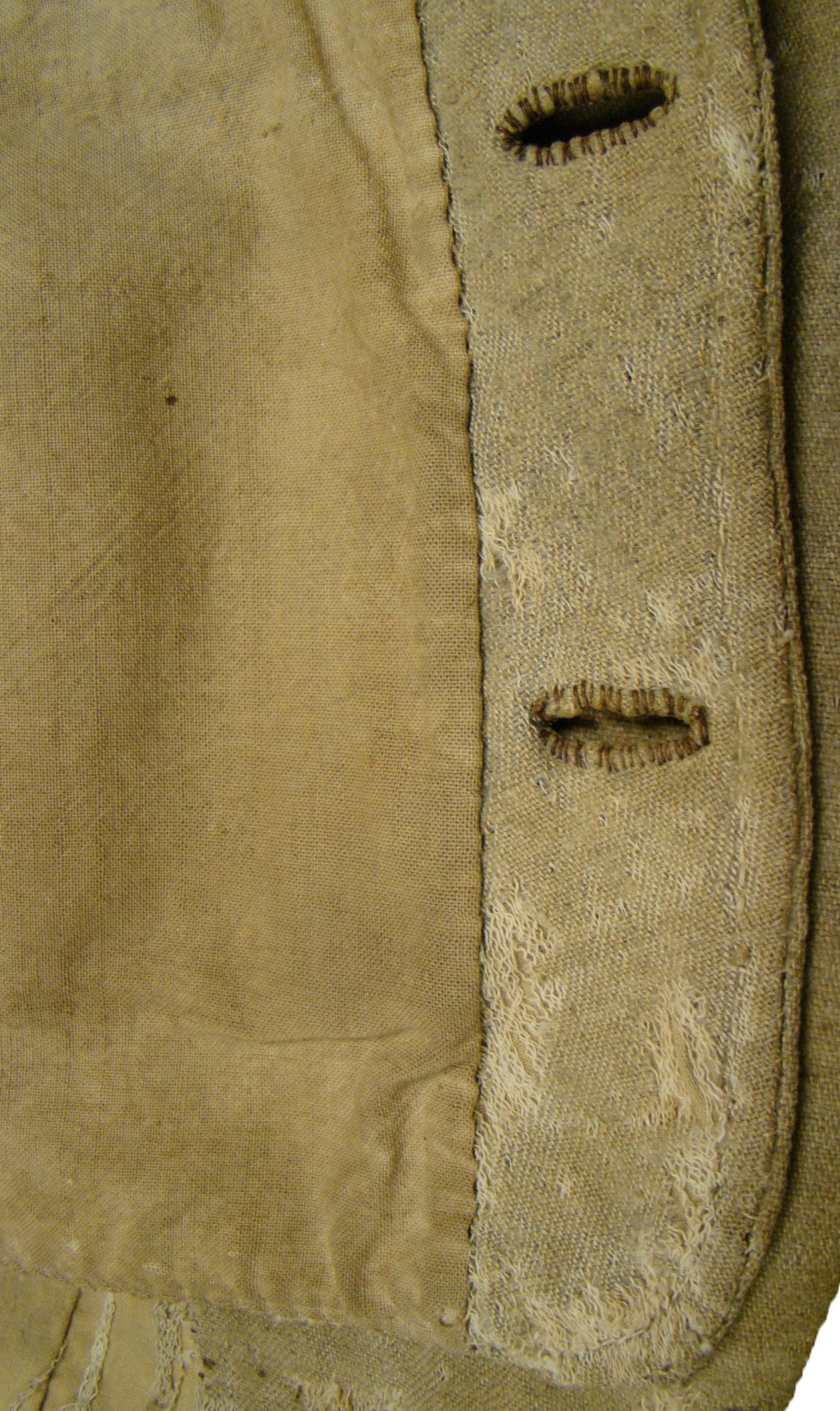

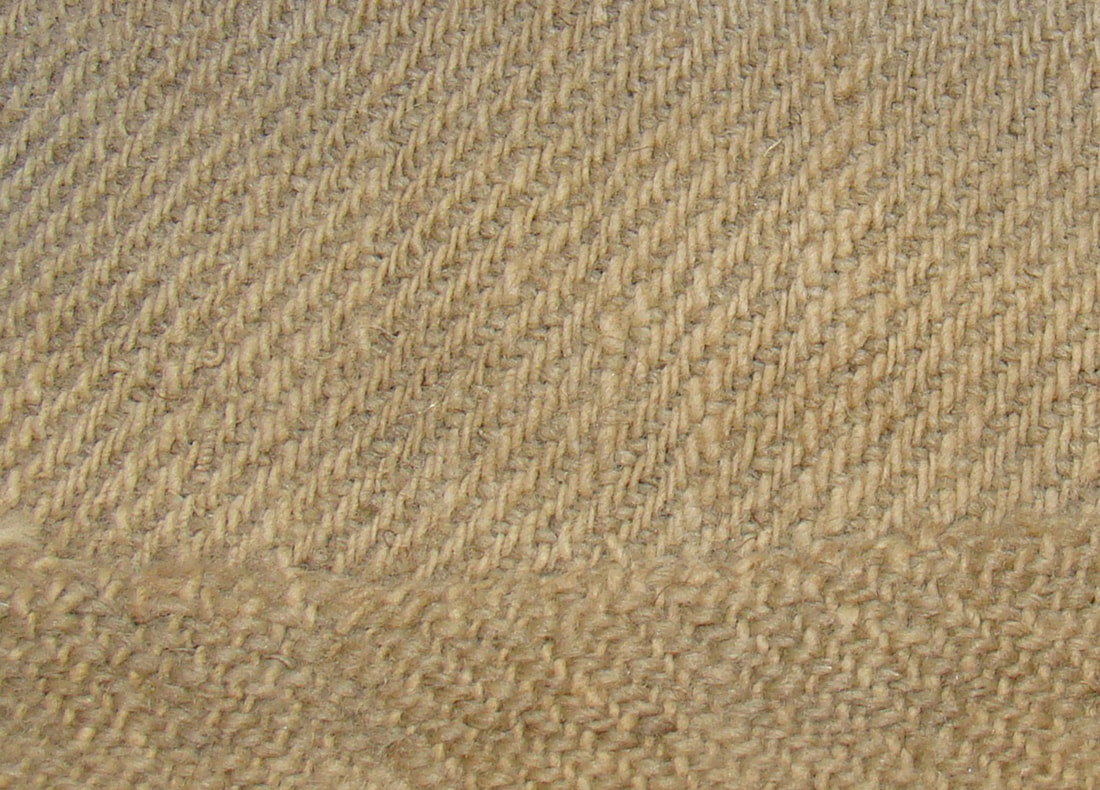

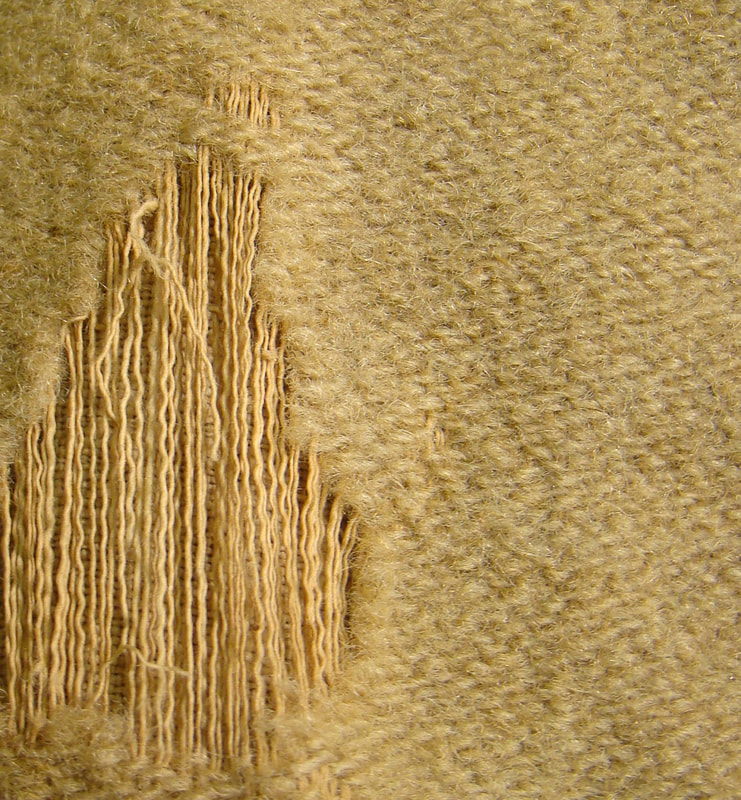

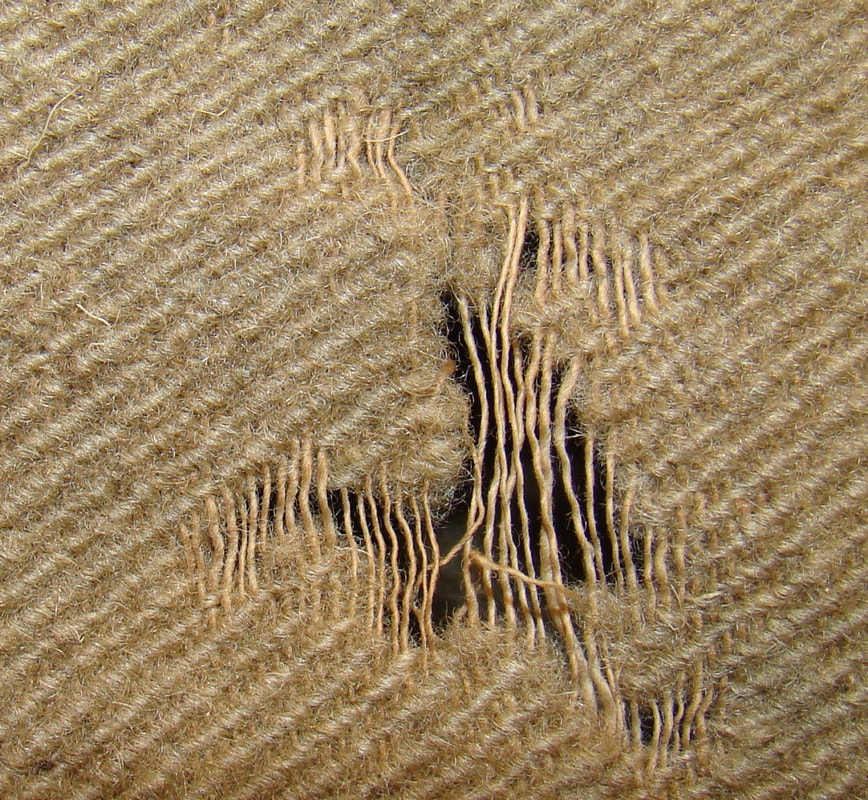

Appler’s jacket is made of woolen-cotton, jeans, that from a short distance appears a light beige color. The cotton warp is a golden-brown color, and the woolen weft a natural white. The weave consists one woolen weft over two and under one cotton warp, and one cotton warp over one and under two woolen weft yarns. The basic cloth appears to have been white originally since the exposed, frayed wool yarns are white. The lining is of unbleached cotton osnaburg. The jacket’s exterior has a four-piece body of two front and two back pieces, one-piece sleeves, and a two-piece collar (inside and out). The jacket has no topstitching around its edge or cuffs. There is one exterior inset pocket on the left front, and one interior patch pocket on the left side that appears to have been added after manufacture. The lining differs from the exterior having separate side and front pieces and a one-piece back. The lapel facings are rather wide. The lining’s back panel is also pieced, having been cut from fabric that was too small to take in the entire pattern size, and two small sections are pieced-in at the sleeve cap. Southern factories occasionally resorted to piecing parts as an economy measure to expend small pieces of fabric. The front of the jacket closes with nine buttons. The buttons are now Federal general service eagle buttons, but Appler may have replaced the originals with these after he received the jacket.

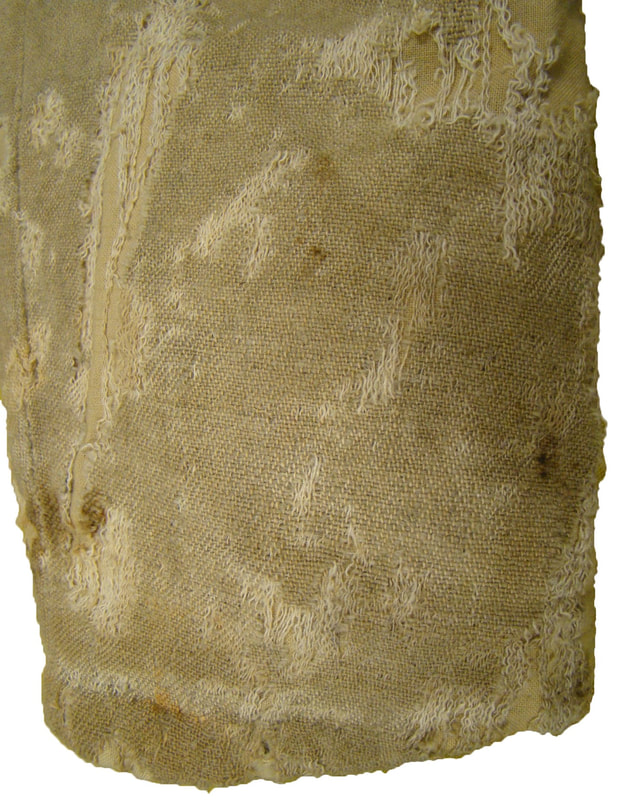

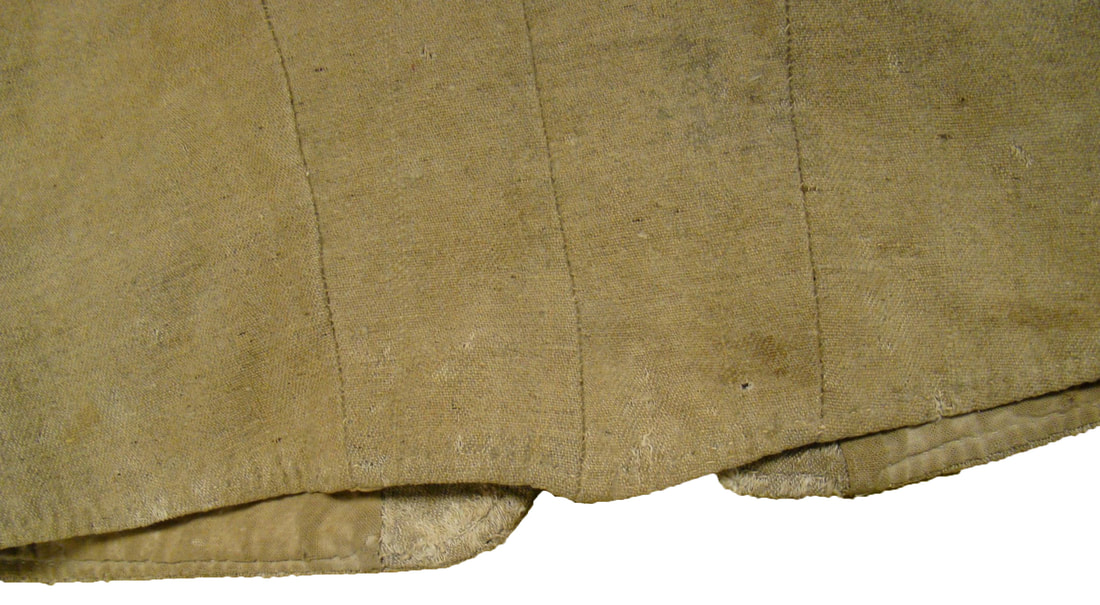

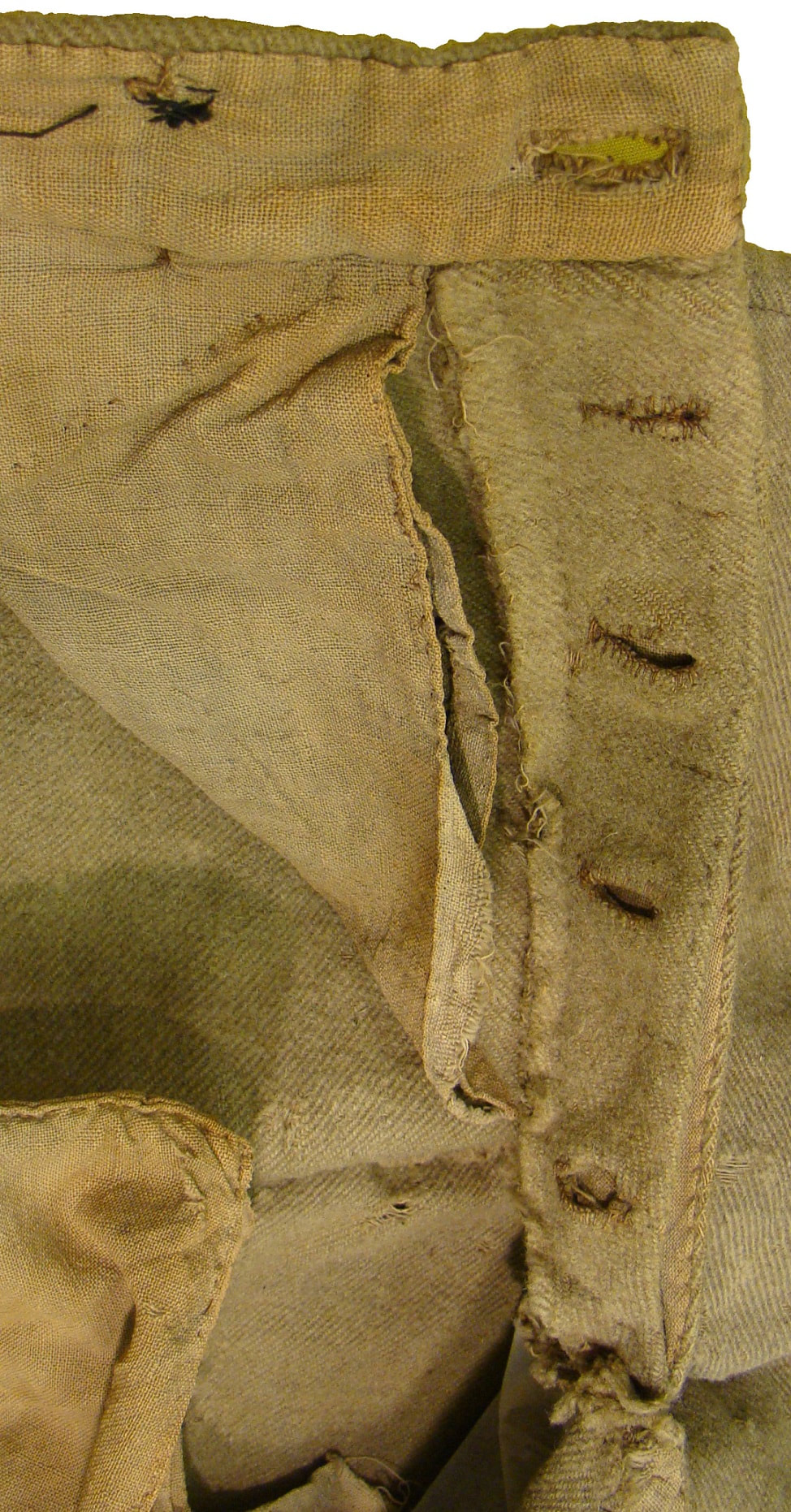

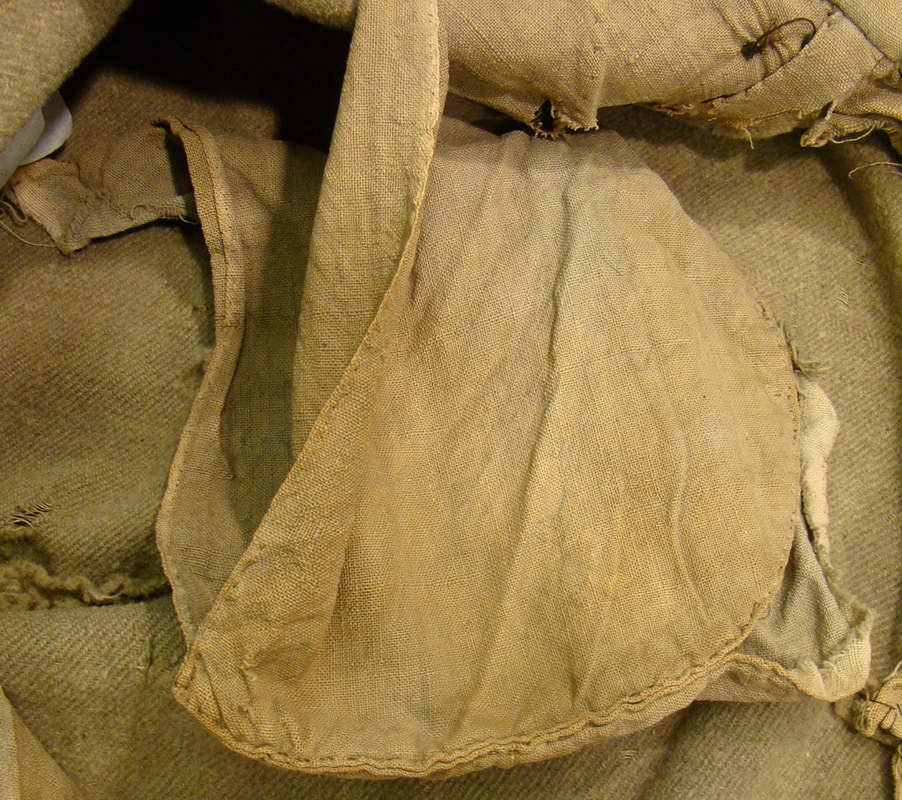

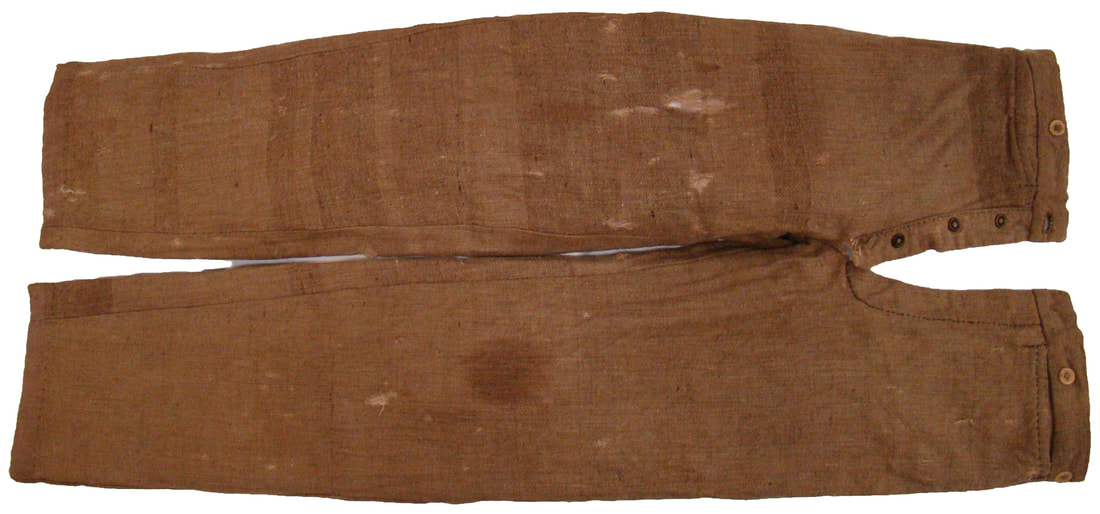

Appler’s trousers are made from the same type of woolen-cotton jeans cloth, and have the same weave (one woolen weft yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarns) as the jacket has. The cotton warp is a tan color, and woolen weft an undyed, natural white. Furthermore, the protected, clean surfaces are distinctly white. Due to some soiling and the tan warp, the overall color has a slight beige tinge. However, some of the exposed, frayed wool yarns are grayish colored and appear to have been dyed. This evidence suggests that the pants cloth was originally gray, and faded to a whitish color. The linings are unbleached white osnaburg. The two front pockets have “V” shaped openings, each with a buttonhole in the corner. The separate waistband has a watch pocket inset on the right side. The left fly component has four lower buttonholes, and the waistband buttonhole is set on the right side, so that the waistband fly button faces inward and closes on the inside of the pants. All of the trousers buttons are intact: five fly, two pocket and six suspender, but one of the suspender buttons is replaced white bone. The original buttons are all stamped, non-japanned tin. The rear leg panels have vertical darts sewn in at the waistband seam, just to the side of the adjustment belt pieces. The adjusting belt at the rear seam has the tongue component on the right side, and the buckle billet on the left. The one-piece, non-swivel buckle is japanned brass. The belt pieces consist of jeans fronts and cotton osnaburg backs, and have identical tailoring with rounded ends. The bottom cuffs are folded inward with the edges tucked into the seamline. These are felled to the legs, but many of the stitches show through to the outside.

The state issued uniforms, made from Huntsville goods, to the Frontier Regiment in 1863. During the first quarter of the year, the state quartermaster manufactured for the regiment: 2,218 pairs of pants, 1,231 coats, 1,179 jackets, 3,491 shirts and 1,659 pairs of drawers. Of this, the regiment drew: 1,620 pairs of pants, 841 coats, 837 jackets, 2,510 shirts and 1,213 pairs of drawers, leaving the balance with the quartermaster. The pants, coats and jackets were made of white kersey and lined with osnaburgs, while the shirts and drawers were made of osnaburgs. No description remains of the buttons used, and not mention was made of having used pant buckles.[27]

The regiment requisitioned cotton jeans and osnaburgs on July 17, 1863 to make 300 coats, 1,000 jackets, 2,000 pairs of pants, 3,000 shirts and 2,000 pairs of drawers. Each coat called for six yards of jeans and two and a half yards of osnaburgs for linings; the jackets required three yards of jeans and two of osnaburgs; and, the pants stated only three yards of jeans were required. The drawers took two and three quarters yards of osnaburgs to make, while the shirts required three yards of osnaburgs each. No mention is made of buttons or pant buckles. What the requisition makes clear, considering how much fabric is required for garment, is that the Huntsville goods were single width, and it took twice as many yards to make each garment as it did with double width fabrics. Jackets were intended for the enlisted troops, and double-breasted frock coats for the officers and sergeants.[28]

The last Frontier Regiment clothing records date from December 1863 to February 1864. During that winter, the regiment was issued clothing and clothing materials (perhaps from the July requisition). The ready-made clothing included “Cavalry Jackets,” pants, over shirts, undershirts, drawers and shoes. Some of the shirts were described as flannel. The cavalry jackets may have been so designated because they had yellow facings, but this is just a guess. The quartermaster issued clothing materials that consisted of cotton jeans and osnaburgs. Cotton jeans was issued out at the rate of six yards per man for coats, along with six yards of osnaburgs for linings, and three yards of jeans per man for pants, along with a half yard of osnaburgs for linings. The cloth was also issued with thread and five buttons (the buttons were probably intended for the pants). Furthermore, some men drew more buttons: some a dozen, and others one and half dozen, making it difficult say how many may have been used for the coat.[29] In any case, all the uniforms were undyed, white, Huntsville cotton jeans.

Moving east, across the Mississippi River into the Lower South, we find much evidence the use of white woolen uniforms. The Confederate quartermaster in Nashville, Tennessee offered premium prices in August and September 1861 for “heavy grey jeans and thick white linsey.”[30] During the same period, the manufacturing city of New Orleans provided an early reference to white uniforms. One of the city’s largest manufacturers of Confederate clothing, Hebrard & Co., made both elaborate and simple uniforms for the Confederate quartermaster. Hebrard’s more elaborate uniforms included “Artillery Uniform Coats and Pants,” and “Infantry Uniform Coats and Pants,” priced at $7.75 each ($5.25 for the coat and $2.50 for the pants). Hebrard made these between February and June 1861, and each suit came with two flannel shirts and two pairs of cotton drawers. By the August-September timeframe, Hebrard had apparently ceased supplying the branch-specific uniforms, and switched to simpler clothing. During that time, he supplied 5,000 suits of “White Kentucky Jeans,” and 300 suits of “Gray Kentucky Jeans” (both at $5.50 per suit); and, 225 suits of “Gray Kersey” at $3.50 per suit.[31] Hebrard’s production of undyed, natural white uniforms reflected a need for quickly-made, mass-produced clothing that was simple, practical and cheap. Doubtless, the Confederate quartermaster was unwilling to pay for expensive, embellished, time-consuming soldier suits. Other New Orleans clothing manufacturers did the same as Hebrard and made simpler uniforms, as well. The New Orleans factories continued to supply the Confederate quartermaster until the Federals occupied the area in April 1862.

Perhaps the most well-known issues of Hebrard uniforms was to the Missouri troops in Northwest Arkansas in early 1862. These were delivered to General Ben McCulloch’s army in the Boston Mountains, and were allotted to the First Missouri Brigade. The clothing included part or all of two shipments of 5,000 white Kentucky jeans suits and osnaburg shirts.[32] Ephraim Anderson of the 2nd Missouri Infantry Regiment recalled when his command received them on March 1-2, “Our regiment was uniformed here; the cloth was of rough and coarse texture, and the cutting and style would have produced a sensation in fashionable circles: the stuff was white, never having been colored, with a goodly supply of grease – the wool had not been purified by any application of water since it was taken from the back of the sheep. In pulling off and putting on the clothes, the olfactories were constantly exercised with a strong odor of that animal.

“Our brigade was the only body of troops that had these uniforms issued to them, and were often greeted with a chorus of ba-a-as… Our clothes, however, were strong and serviceable, if we did look and feel somewhat sheepish in them.”

This issue of clothing was also described by James Harding, the Quartermaster General for the Missouri troops. Harding distributed uniforms and accouterments to Burbridge’s 2nd Missouri Infantry, and, in part, to Rives’ 3rd Missouri Infantry. The issue was made in the Missouri camp at Cove Creek, Arkansas, probably in late February 1862. Harding reported, “Advantage was taken… to issue to the troops the clothing, blankets, etc., which had been so long in the wagons, and which there was great need… the jackets and pants were of white linsey, with big wooden buttons, with which Rives and Burbridge’s regiments were furnished… These clothes were real nigger clothing, but were warm, of good material, were uniform in color, and far preferable to no clothes at all. The black belts and equipments set of [sic] the linsey very nicely, and the regiment looked really well in their working clothes.”[33]

Another famous story about the mass-produced, white, New Orleans-made uniforms comes from the 2nd Texas Infantry Regiment. The regiment’s commander, Colonel J.W. Moore, had sent a requisition for gray uniforms to the Confederate quartermaster at New Orleans prior to his regiment departing Houston, Texas on March 18, 1862. The cloth used to make these uniforms was from one of Irby Morgan’s last consignments of Huntsville goods to the Nashville quartermaster. Since Nashville had fallen, Morgan had the cloth sent to New Orleans. Morgan had promised to make the 2nd Texas Infantry Regiment’s uniforms from these woolens.[34] When the regiment arrived in Corinth, Mississippi, on April 1, 1862, and Moore recalled:

“When my regiment, the Second Texas Infantry, was organized, at Galveston in 1861, not being able to procure Confederate gray, the men were supplied with Federal blue uniforms captured at Texas military posts. When, in March, 1862, we were ordered to report to Gen. A.S. Johnston, then at Corinth, we marched across the country to Alexandria, and thence were conveyed by steamer and railroad to our destination.

“Not believing Federal blue a life prolonging color for a Confederate uniform in battle, I sent an agent with a requisition on the quartermaster at New Orleans for properly colored uniforms. He met us at Corinth a few days before marching for the Shiloh (or Pittsburg Landing) battlefield. When the packages were opened, we found the so-called uniforms as white as washed wool could make them. I shall never forget the men’s consternation and many exclamations not quoted in the Bible, such as, “Well, I’ll be d-----!,” “Don’t them things beat h---!,” “Do the generals expect us to be killed, and want us to wear our shrouds?,” etc. Being a case of Hobson’s choice, the men cheerfully made the best of the situation, quickly stripped off the ragged blue and donned the virgin white. The clothing having no marks as to sizes, articles were issued just as they came, hit or miss as to fit. Soon the company grounds were full of men strutting up and down, some with trousers dragging under their heels, while those of others scarcely reached the tops of their socks; some with jackets so tight they resembled stuffed toads, while others had ample room to carry three days’ rations in their bosoms. The exhibition closed with a swapping scene that reminded one of a horse-trading day in a Georgia country town. A Federal prisoner at Shiloh inquired: “Who were them hell-cats that went into battle dressed in their graveclothes?”[35]

Significantly, the white woolen uniforms represented a trend in manufacturing. The Confederate factories in Mississippi would produce, and the Army of Mississippi would wear white woolen uniforms for much of the war. Additionally, the Texans’ uniform consignment was one of the last to leave New Orleans for the Confederate army, and it highlights how important the city was in supplying clothing to the Confederacy.

At least one factory in Mississippi left a record of having made white cloth for the Confederate quartermaster, although there may have been more. James M. Wesson’s Mississippi Manufacturing Company at Bankston furnished woolen linseys and jeans to the quartermaster from late 1861 to at least August 1863. In September 1862, Wesson sold “W Jeans,” “Bro Jeans,” and “W Linseys” to the Confederate quartermaster at Jackson. The abbreviations probably stand for “white” and “brown.” He also furnished jackets to the Selma quartermaster in 1863, that were described as “linsey,” and could have been white linsey.[36]

There are both written accounts and surviving artifacts that document the use of white uniforms in Mississippi. Willie H. Tunnard of the 3rd Louisiana Infantry wrote that his command received the white uniforms at Snydor’s Mill, in mid-March 1863, prior to March 22nd. Tunnard recounted the event: “The regiment received a new uniform, which they were ordered to take, much against their expressed wishes. The material was a very coarse white jeans, ‘Nolen Volens.’ The uniforms were issued to the men, few of whom would wear them, unless under compulsion, by some special order. On March 22nd orders were issued to cook three days’ rations, and be prepared to move ere daylight the succeeding morning. The weather was gloomy and rainy, the roads in a terrible condition. Some of the men suggested the propriety of wearing the new white uniforms on the approaching expedition, which, it was known, would be among the swamps of the Yazoo Valley. The suggestion was almost universally adopted, affording a rare opportunity to give the new clothes a thorough initiation into the mysteries of a soldier’s life. Thus the regiment assembled the next morning arrayed as if for a summer’s day festival.”[37]

The 26th Louisiana Infantry Regiment received the same type of white uniform that March, as well. The 26th Louisiana had similar misgivings about the new uniforms. Their regimental commander, Colonel Winchester Hall, recorded that,

“About this time [March 1863] we received at Vicksburg the fruits of the conscript levees in Louisiana. The men so raised were placed in various Louisiana commands, after receiving a white woolen uniform. The uniform was unlike any other about us, and marked these men among the volunteer soldiers, who treated them with a contempt, in many cases, undeserved; but so it was the white uniform was known only as an emblem of reproach wherever it appeared.

“Soon after these men were in harness, our regiment received the same kind of uniform; now the Quarter Master's Department of the 26th was never so plethoric as to supply our mere necessities in this line, and a suit of clothes all around was a rare occasion. The clothing was sorely needed, but a howl of indignation rose from the regiment, at the bare suggestion of wearing the badge of a conscript. The indignation was intensified by the fact that none of the conscripts had been put into the ranks of the 26th, and its integrity as a volunteer organization was intact.

“Comfort, appearance, everything was forgotten in the thought that henceforth men who had sought the ranks, and men who had been impressed into service, would be blended, by the uniform, into an undistinguishable mass. The indignation seemed so becoming a volunteer, that officers were loath to invoke the coercive measures in their power. They appealed to the men, and showed the folly of giving away to a fancy. One company after another, in time, yielded to what appeared to be inevitable, until Company B — staunch old hearts — stood out alone. Captain Bateman, however, never relaxed his efforts to kindly bring them to a sense of duty, until only two of the company stood out. The Captain reported the case to me. I ordered the men to be tied up by the thumbs until they were disposed to obey the orders of their Captain. They soon relented, but I fear not willingly.”[38]

By the time of the battles around Vicksburg, the white uniform seems to have been commonplace among the Confederate troops in Mississippi. Lieutenant Anthony B. Burton of the 5th Ohio Battery reported that Cummings’ Georgia Brigade was clothed in undyed wool uniforms at the siege of Vicksburg.[39]

The first concrete example of depot-issued white Confederate clothing pants, presented herein, is the uniform worn by John Thomas Appler, Company H, 1st Missouri Infantry, in Mississippi, May 1863. The uniform is significant because it represents not only a relatively early war example, but also, it is the only surviving white woolen uniform of the Army of Mississippi, a uniform type that was common during the campaigns for Vicksburg in 1862 and 1863. The uniform consists of a jacket and pair of trousers.[40]

Appler was wounded at Champion Hill when a ball went completely through his left ankle. He was left on the field when the Confederate army retreated, and taken prisoner. Soon thereafter, he was released and sent to Confederate lines where he received care at the hospitals in Jackson, Mississippi, and Mobile, Alabama. Due to his debilitating wound, he was furloughed in October and went home to Hannibal, Missouri. There, he was captured, sent to a Federal hospital and eventually paroled March 8, 1864, at which time his military service effectively ended.[41]

Regarding the provenance of his uniform, he may have worn it at the Champion Hill, but there is a better chance that he got the uniform when he was in the 1st Mississippi CSA Hospital in Jackson. The latter possibility makes sense, because the pants do not show signs of a bullet hole or blood stains. Furthermore, Appler would likely have gotten clean, new clothing when he went to the hospital. He may also have gotten only a new pair of pants to place the blood-stained, damaged ones, and kept his old jacket. Not that this has any bearing upon the origins of his uniform. Whether he got it before Champion Hill or in the Hospital afterwards, the uniform still came from a Confederate factory in Mississippi, and still represents the white woolen type so common to the Army of Mississippi.

Appler’s jacket is made of woolen-cotton, jeans, that from a short distance appears a light beige color. The cotton warp is a golden-brown color, and the woolen weft a natural white. The weave consists one woolen weft over two and under one cotton warp, and one cotton warp over one and under two woolen weft yarns. The basic cloth appears to have been white originally since the exposed, frayed wool yarns are white. The lining is of unbleached cotton osnaburg. The jacket’s exterior has a four-piece body of two front and two back pieces, one-piece sleeves, and a two-piece collar (inside and out). The jacket has no topstitching around its edge or cuffs. There is one exterior inset pocket on the left front, and one interior patch pocket on the left side that appears to have been added after manufacture. The lining differs from the exterior having separate side and front pieces and a one-piece back. The lapel facings are rather wide. The lining’s back panel is also pieced, having been cut from fabric that was too small to take in the entire pattern size, and two small sections are pieced-in at the sleeve cap. Southern factories occasionally resorted to piecing parts as an economy measure to expend small pieces of fabric. The front of the jacket closes with nine buttons. The buttons are now Federal general service eagle buttons, but Appler may have replaced the originals with these after he received the jacket.

Appler’s trousers are made from the same type of woolen-cotton jeans cloth, and have the same weave (one woolen weft yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarns) as the jacket has. The cotton warp is a tan color, and woolen weft an undyed, natural white. Furthermore, the protected, clean surfaces are distinctly white. Due to some soiling and the tan warp, the overall color has a slight beige tinge. However, some of the exposed, frayed wool yarns are grayish colored and appear to have been dyed. This evidence suggests that the pants cloth was originally gray, and faded to a whitish color. The linings are unbleached white osnaburg. The two front pockets have “V” shaped openings, each with a buttonhole in the corner. The separate waistband has a watch pocket inset on the right side. The left fly component has four lower buttonholes, and the waistband buttonhole is set on the right side, so that the waistband fly button faces inward and closes on the inside of the pants. All of the trousers buttons are intact: five fly, two pocket and six suspender, but one of the suspender buttons is replaced white bone. The original buttons are all stamped, non-japanned tin. The rear leg panels have vertical darts sewn in at the waistband seam, just to the side of the adjustment belt pieces. The adjusting belt at the rear seam has the tongue component on the right side, and the buckle billet on the left. The one-piece, non-swivel buckle is japanned brass. The belt pieces consist of jeans fronts and cotton osnaburg backs, and have identical tailoring with rounded ends. The bottom cuffs are folded inward with the edges tucked into the seamline. These are felled to the legs, but many of the stitches show through to the outside.

The best photograph that documents the white, Mississippi-made uniform is of a paroled soldier from the Port Hudson garrison, ca. July 1863. The soldier, L. Cormier, served in Boone’s Louisiana Artillery Battery. He wears a suit of matching white jacket and pants. The jacket is typical of most Confederate jackets as far as is visible in the picture, and includes shoulder straps. The pants have been ironed with a crease in them, and the front pockets appear to be side opening. This may have been the uniform he wore at Port Hudson, or a fresh one that he received in his parole camp. The latter is probably the case since the uniform appears clean and in excellent condition. In any case, it is typical of what the quartermaster issued in Mississippi during 1863.[42]

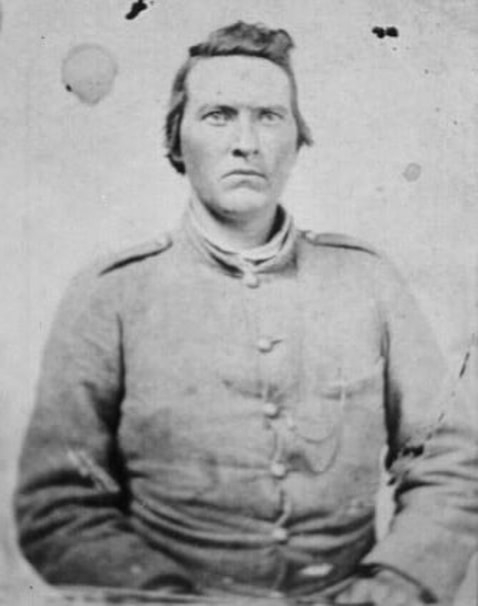

Image 3: This image shows L. Cormier of Boone’s Louisiana Battery while he was a prisoner in New Orleans, July 1863. Cormier wears a white jacket (and perhaps white pants, too) that he may have worn during the Vicksburg Campaign. Image courtesy of Port Hudson State Commemorative Site, Louisiana. Commemorative Area.

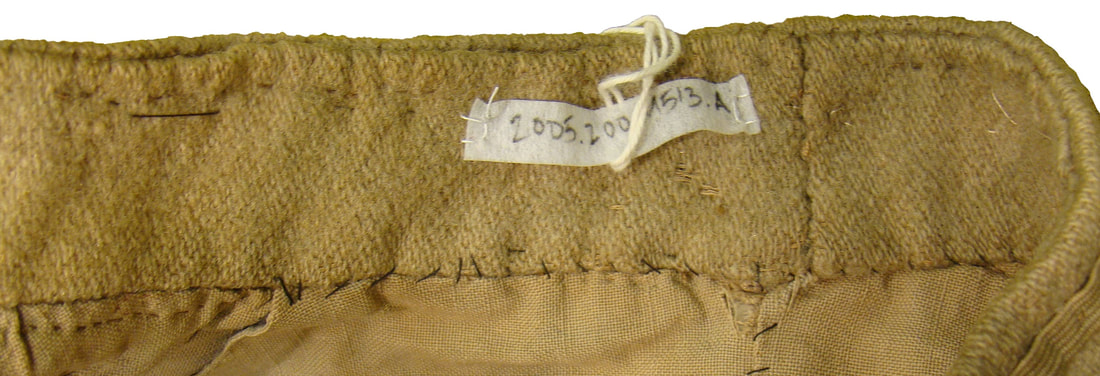

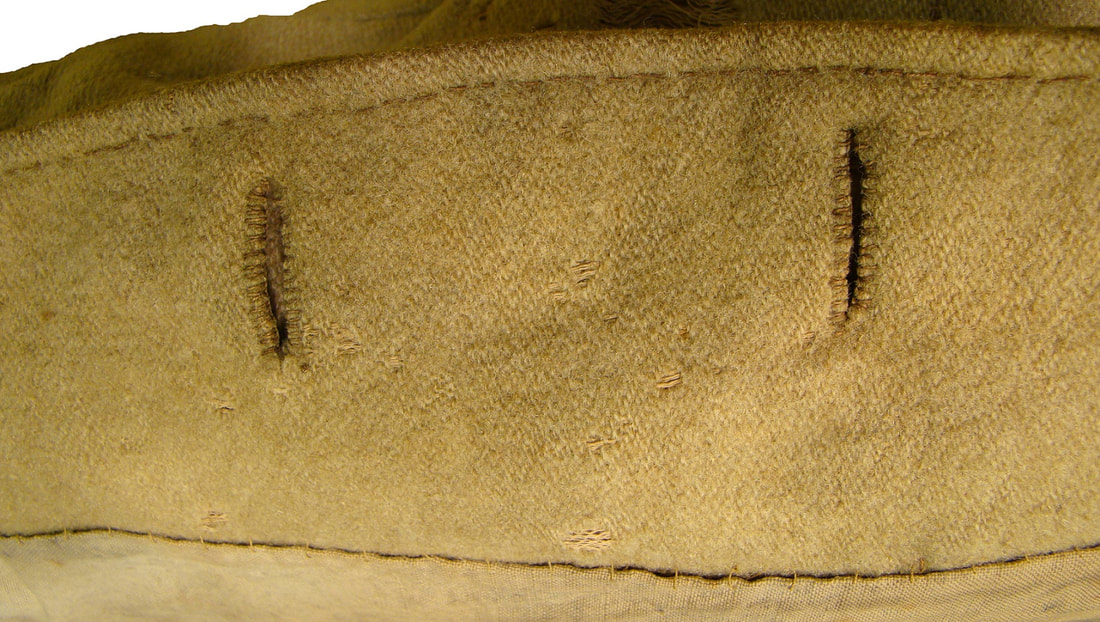

The next example of depot-issued, white Confederate clothing is a pair of pants worn by Private Nathan Tisdale, Company A, 30th Louisiana Infantry. Tisdale’s pants have provenance to the Mississippi-Alabama region. According to Tisdale’s wife, who donated them to Confederate Memorial Hall in 1902, Tisdale wore these pants when he has wounded at the Battle of Spanish Fort, 1865. Tisdale participated in the Tennessee Campaign of 1864, and remained in the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana, afterwards. He was sent to the Quintard Confederate Hospital, Griffin, Georgia, after being wounded at Spanish Fort, and is listed on a roll of prisoners there in May 1865. He was officially surrendered at Citronelle, Alabama, on May 4, 1865, and paroled at Meridian, Mississippi, on May 10, but this may have been a formality since he was apparently in the hospital at Griffin, Georgia.[43] Tisdale probably received his trousers while stationed at Mobile. If such was the case, Tisdale’s pants would have been issued from either the Montgomery, Alabama, or Columbus, Mississippi Depot during the last months of the war. The pants’ worn and dirty condition lend credence to his wife’s story that he wore them in battle during the spring of 1865.

Tisdale’s trousers are remarkable in that the original, unsullied color of the fabric is visible on the protected surface under the right belt piece: the trousers are made of white woolen-cotton jeans cloth. The fabric weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarns. It has a heavy, bleached white cotton warp, and a white woolen weft. Due to heavy soiling, the overall color of the jeans is now a grayish-beige in color, except where protected surfaces retain the original, natural white shade. The trousers’ linings and facings are of heavy, unbleached white cotton drill, not osnaburg. This is relevant because quartermasters in Montgomery and Selma used white cotton drills for this purpose, and this may be a clue that these are Montgomery Depot pants. The lining is likewise soiled, except for a few protected surfaces.

The trousers’ most salient tailoring feature is the front pocket construction. The two front pockets are top-opening in the manner of watch pockets. This pocket style was preferred by many soldiers. The openings have facing jeans welts along both to the inside and outside parts of the cotton drill pocket bags. Tisdale’s pants are made nearly identically to a pair of unidentified Confederate pants in the Smithsonian Institution collection, identified only by its catalog number: U-083. The U-083 pants are believed to have been made in a Mississippi factory, because the pants’ cloth is the same as that associated from provenance uniforms from the region.

The fly is made with four buttonholes: three on the lower fly and one at the waistband. The only fly button remaining is a very rusty, stamped iron pants button at the waistband. The waistband retains its six, four-hole, natural white bone suspender buttons; two on each side in front and two in the rear.

The adjusting belt at the rear seam has the tongue portion on the left side, and the buckle portion on the right. The buckle is now missing, but it left rust stains on both belt straps that show it was iron. The belt pieces consist of jeans fronts and cotton drill backs, and have identical tailoring with rounded ends. The end of the right belt piece is missing where it was folded over to hold the buckle.

Tisdale’s pants are lined as follows. The insides of the cuffs have cotton drill reinforcing bands sewn around the hemmed edge. The fly facings, waistband and reinforcing yoke pieces are also of cotton drill.[44]

Tisdale’s trousers are remarkable in that the original, unsullied color of the fabric is visible on the protected surface under the right belt piece: the trousers are made of white woolen-cotton jeans cloth. The fabric weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarns. It has a heavy, bleached white cotton warp, and a white woolen weft. Due to heavy soiling, the overall color of the jeans is now a grayish-beige in color, except where protected surfaces retain the original, natural white shade. The trousers’ linings and facings are of heavy, unbleached white cotton drill, not osnaburg. This is relevant because quartermasters in Montgomery and Selma used white cotton drills for this purpose, and this may be a clue that these are Montgomery Depot pants. The lining is likewise soiled, except for a few protected surfaces.

The trousers’ most salient tailoring feature is the front pocket construction. The two front pockets are top-opening in the manner of watch pockets. This pocket style was preferred by many soldiers. The openings have facing jeans welts along both to the inside and outside parts of the cotton drill pocket bags. Tisdale’s pants are made nearly identically to a pair of unidentified Confederate pants in the Smithsonian Institution collection, identified only by its catalog number: U-083. The U-083 pants are believed to have been made in a Mississippi factory, because the pants’ cloth is the same as that associated from provenance uniforms from the region.

The fly is made with four buttonholes: three on the lower fly and one at the waistband. The only fly button remaining is a very rusty, stamped iron pants button at the waistband. The waistband retains its six, four-hole, natural white bone suspender buttons; two on each side in front and two in the rear.

The adjusting belt at the rear seam has the tongue portion on the left side, and the buckle portion on the right. The buckle is now missing, but it left rust stains on both belt straps that show it was iron. The belt pieces consist of jeans fronts and cotton drill backs, and have identical tailoring with rounded ends. The end of the right belt piece is missing where it was folded over to hold the buckle.

Tisdale’s pants are lined as follows. The insides of the cuffs have cotton drill reinforcing bands sewn around the hemmed edge. The fly facings, waistband and reinforcing yoke pieces are also of cotton drill.[44]

Image 5a: As a comparison to Tisdale's pants, the U-083 pants are shown here. The cut of both pants is the same and they were likely made by the same factory. All the 5-series images of the U-083 pants are courtesy of the Armed Forces History Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Another pair of white trousers with an Alabama provenance belonged to C.W. Mitchell, Company F, 7th Alabama Cavalry. Mitchell joined the army in 1863 at 16 years of age. His regiment fought in the Tennessee Campaign, where he was severely wounded in the left leg at Mount Pleasant, Tennessee. His next available record is his parole at Montgomery, dated May 9, 1865.[45] Mitchell wore these trousers when he was wounded. He did not lose his left leg, but the hospital staff cut away the lower left pant leg to treat his wound. He probably received these pants when the regiment was stationed in the Pollard area (close to Mobile) just prior to joining the Army of Tennessee the late summer of 1864. Assuming this to be the case, the pants would likely have been from one of the department’s depots. The pants are similar to a pair in the Gettysburg National Park collection, identified only as the GETT 29077 trousers, and were presumably made at the same factory.[46] The pants’ weave is one woolen yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarn, and cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen yarn. Both the woolen weft and the cotton warp yarns are a natural white color, the cotton being slightly lighter than the wool. The overall color is now a natural white with a very slight tannish cast, but when they were issued, they were apparently a cleaner natural white. All the buttons are missing except for the waistband fly button, a five-eighths inch pants size, wooden button made by W.C. Allen’s Prattville, Alabama button factory. The pockets have “V” shaped openings. The rear adjustment belt has two buttonholes on the right piece and had one or two Allen buttons on the left piece that are now missing. The buttoning, rear adjustment belt closely matches that of the GETT 29077 pants. The fly has four buttonholes: one at the waistband and three in the fly piece. The pants are lined with unbleached osnaburg. The pants pieces have quarter-inch seam allowances.[47]

Moving eastwards into Georgia, there is substantial evidence for the prevalence of white Confederate clothing. An interesting report filed by the Savannah quartermaster for clothing on-hand, October 31, 1863, alludes to both undyed sheep’s gray and white uniforms. The descriptions included the following: 800 Pantaloons, Georgia homespun, manufactured in Savannah of a strong fabric, light gray color, rather thin for winter; 6,700 pantaloons, Georgia jeans, fairly good quality, of an off light-gray color; a lot of 1,400 jackets and pants made of Georgia homespun (the suits were furnished by the State of Georgia), to be issued only as a last resort, being “… a poor article… thin for the season, and almost white [in color].”[48] Further details mention that there were wooden buttons on the Georgia jeans cloth, infantry jackets.

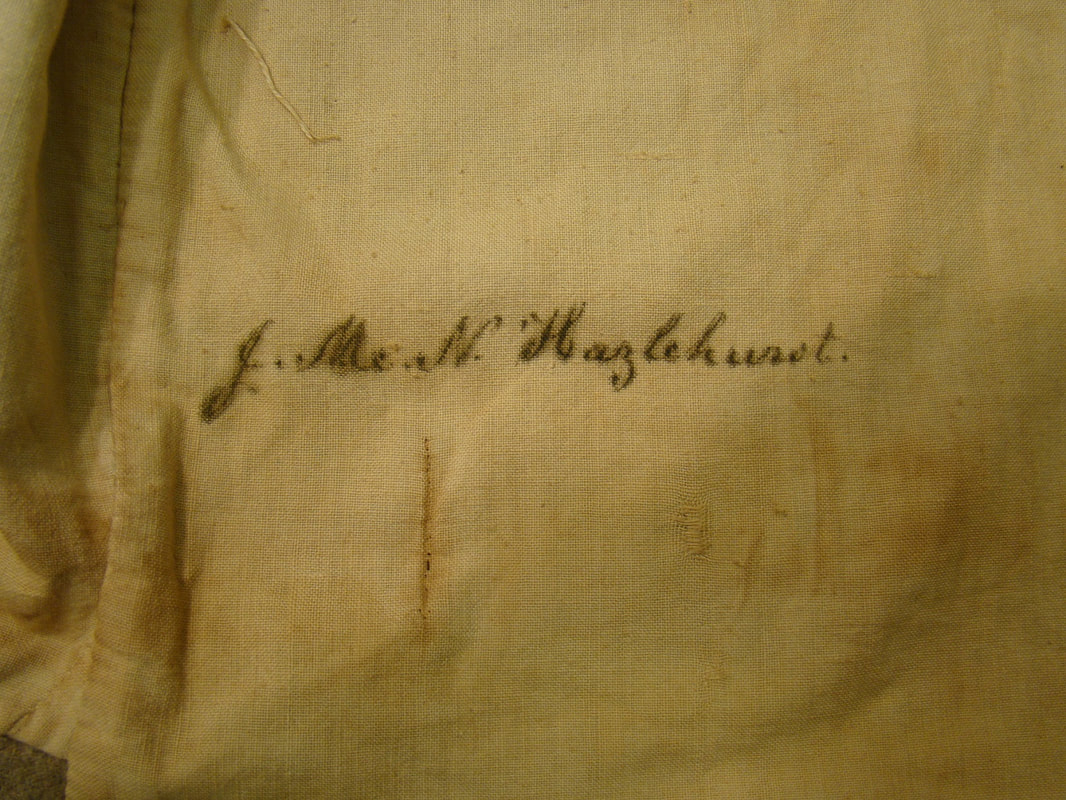

The white woolen jacket of John Britten Lewis Grizzard offers an excellent example of this type of uniform. Grizzard was from Fulton County, Georgia, and he joined the Confederate Army in Atlanta on February 3, 1864, along with James L. Grizzard, and Simeon S. Grizzard. The others were certainly close relatives, and may have been his brothers. All three men enlisted in Hanleiter’s Company, Georgia Light Artillery for three years. They probably chose this outfit because their relative, Thaddeus Grizzard, was already in the company, having enlisted on September 17, 1863.

Private John B. L. Grizzard served with the company from February through at least October 31, 1864. There are no later records of his service. His meager records indicate that he was absent without leave from May 27 to June 20, 1864, and that the army deducted his pay for the days he was absent. He also received clothing shortly after joining the army, on February 22, 1864. Part of that issue may have included the white woolen jacket featured in this study. Nothing else is known of his service, and he died two years after the war. He was buried at Union City, Georgia.

Hanleiter’s Battery had been formed on June 10, 1862 from Company M, 38th Georgia Infantry. The 38th Georgia was formed with thirteen companies in the summer of 1861. The regiment served in the Savannah area, until it was transferred to Virginia in May 1862. Three of the regiment’s thirteen companies were detached and did not accompany the regiment (Company M being one of these). Company M remained in the Savannah area and reorganized as an artillery company in June. The company, commanded by Captain Cornelius R. Hanleiter, served both light and heavy guns. It remained near Savannah until December 20, 1864, when it withdrew to Charleston, South Carolina with the rest of the retreating Confederate Army. The company continued the retreat away from Sherman’s army on January 14, 1865, leaving Charleston, and moving towards North Carolina. Hanleiter’s Battery fought during the Carolina Campaign, and finally surrendered at Greensboro on April 26, 1865.