The Quintessential Confederate Cap, Part III: Caps of the Lower South

Fred Adolphus, 23 June 2023

Continued from Part II: click here to navigate back to the previous page...

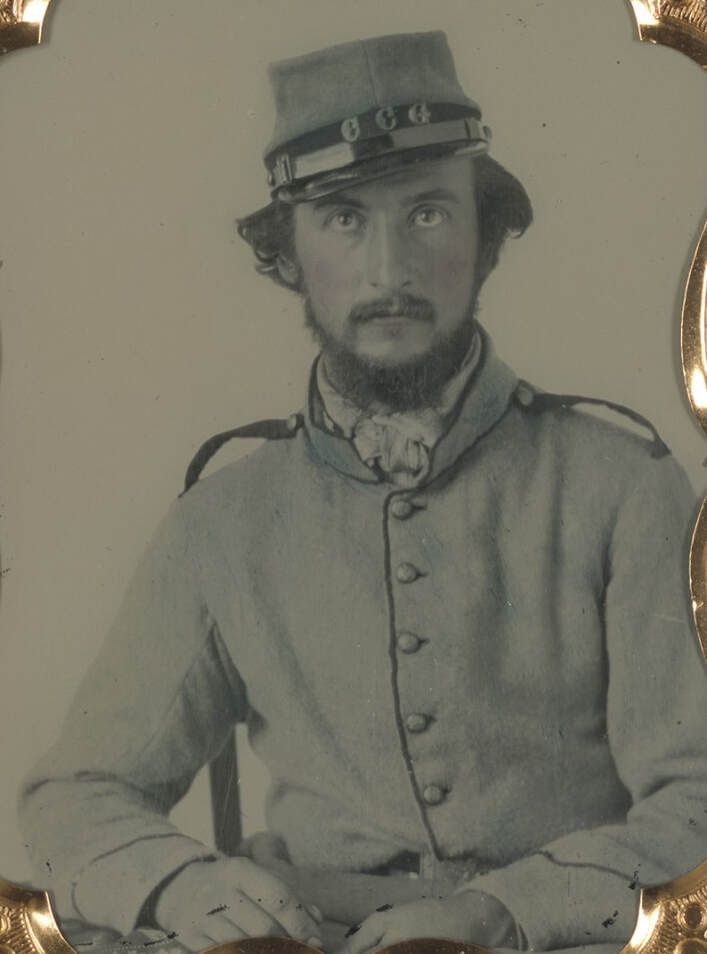

Nashville, Little Rock and New Orleans Quartermaster Caps

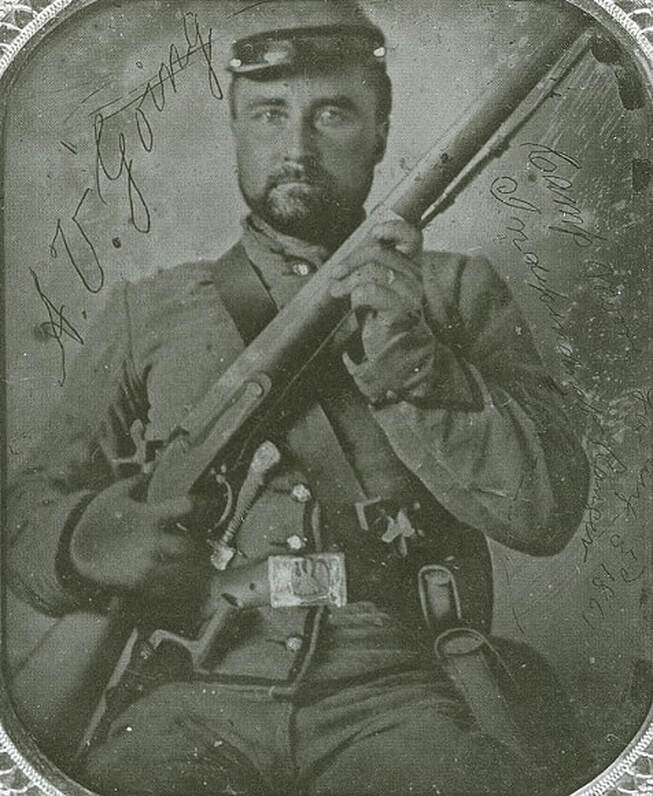

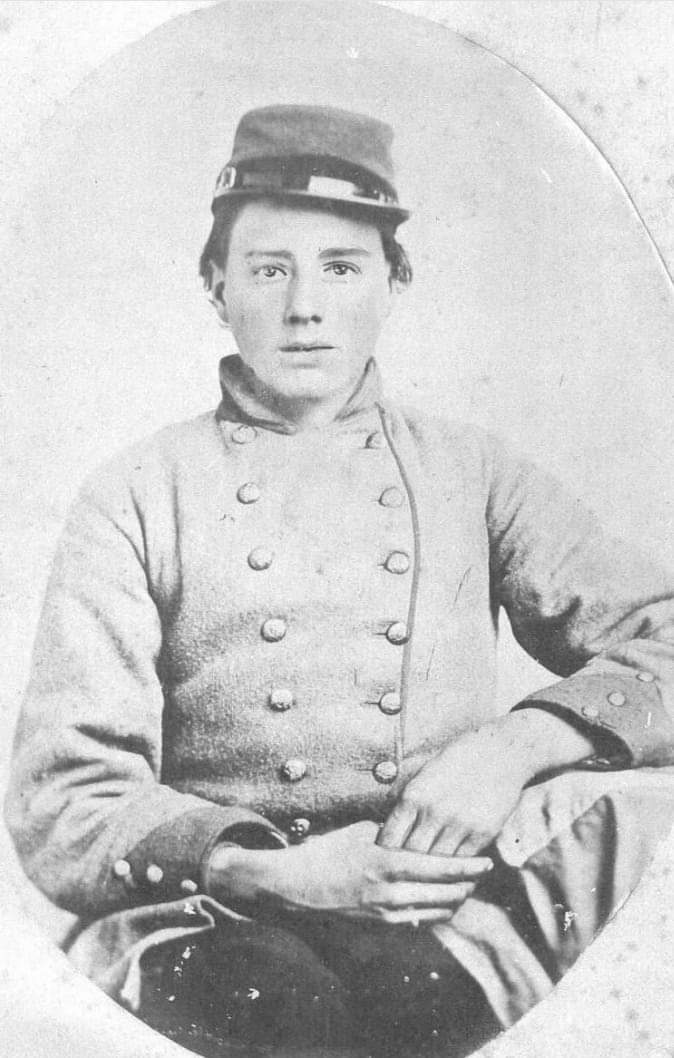

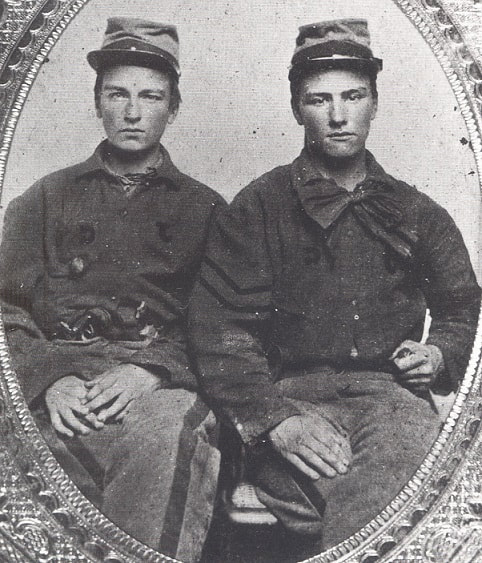

The Tennessee Quartermaster, along with New Orleans and Little Rock, established one of the earliest clothing manufactories in the South by early 1861. The chief manufacturing hub was centered around Nashville, but it had operations in the outlaying cities of Memphis and Knoxville, as well. These operations produced, or procurred significant quantities of clothing until they were compelled to close in early 1862 due to the withdrawal of Confederate forces from the area. Sales invoices in Nashville and Knoxville from September 1861 to February 1862 show that the quartermasters purchased 24,796 caps.[56] The Tennessee quartermaster appears to have produced a universal gray chasseur cap with a black band. Early war images bear out this assertion and contemporary observations support the thesis, too. For instance, the Carlyle Weekly Reveille [Illinois] remarked about Confederate clothing in Tennessee on 23 February 1862, noting a general lack of uniformity, that it was made of coarse jeans dyed with walnut bark, and that the pants mostly had a broad black stripe down the outer seam. “Hats and caps were diversified, yet they had a uniform cap – gray with a black band.”[57] A soldier of the 95th Illinois Infantry remarked on 15 December 1862, after the Battle of Corinth, about Confederate prisoners, “Nearly eight hundred Rebel prisoners passed by late in the afternoon. They were nearly all clad in butternut suits with a gray cap.”[58]

During the spring of 1861, when the Tennessee quartermaster began manufacturing significant quantities of clothing for the Confederacy, Arkansas authorities established a large clothing manufacturing center in Little Rock. Likewise, the industrial hubs at New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana began fabricating clothing en masse. Both Little Rock and the Louisiana operations used black cloth for uniform trimmings. This is reflected in soldier images, surviving artifacts and written records. The gray chasseur cap with a black band, common to the Tennessee factories, appears to have been made by the Arkansas and Louisiana quartermasters, as well.

Two surviving caps are offered as examples of the prominent, and nearly universal, early-war, Western cap with a black band. These come from the collections of Gary Hendershott and Allen Wandling. The Hendershott collection cap is without provenance, but the Wandling collection cap is attributed to Private G.L. Lacozi, 3rd Louisiana Infantry. Whether the caps were made in Tennessee, Arkansas or Louisiana, or even elsewhere, is uncertain. They are, nonetheless, representative of the type. There are also numerous surviving images of soldiers wearing this style of cap from throughout the region. The Nashville and New Orleans manufacturing hubs shut down upon federal occupation in early 1862, and their production was shifted to the interior of Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia.

Nashville, Little Rock and New Orleans Quartermaster Caps

The Tennessee Quartermaster, along with New Orleans and Little Rock, established one of the earliest clothing manufactories in the South by early 1861. The chief manufacturing hub was centered around Nashville, but it had operations in the outlaying cities of Memphis and Knoxville, as well. These operations produced, or procurred significant quantities of clothing until they were compelled to close in early 1862 due to the withdrawal of Confederate forces from the area. Sales invoices in Nashville and Knoxville from September 1861 to February 1862 show that the quartermasters purchased 24,796 caps.[56] The Tennessee quartermaster appears to have produced a universal gray chasseur cap with a black band. Early war images bear out this assertion and contemporary observations support the thesis, too. For instance, the Carlyle Weekly Reveille [Illinois] remarked about Confederate clothing in Tennessee on 23 February 1862, noting a general lack of uniformity, that it was made of coarse jeans dyed with walnut bark, and that the pants mostly had a broad black stripe down the outer seam. “Hats and caps were diversified, yet they had a uniform cap – gray with a black band.”[57] A soldier of the 95th Illinois Infantry remarked on 15 December 1862, after the Battle of Corinth, about Confederate prisoners, “Nearly eight hundred Rebel prisoners passed by late in the afternoon. They were nearly all clad in butternut suits with a gray cap.”[58]

During the spring of 1861, when the Tennessee quartermaster began manufacturing significant quantities of clothing for the Confederacy, Arkansas authorities established a large clothing manufacturing center in Little Rock. Likewise, the industrial hubs at New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana began fabricating clothing en masse. Both Little Rock and the Louisiana operations used black cloth for uniform trimmings. This is reflected in soldier images, surviving artifacts and written records. The gray chasseur cap with a black band, common to the Tennessee factories, appears to have been made by the Arkansas and Louisiana quartermasters, as well.

Two surviving caps are offered as examples of the prominent, and nearly universal, early-war, Western cap with a black band. These come from the collections of Gary Hendershott and Allen Wandling. The Hendershott collection cap is without provenance, but the Wandling collection cap is attributed to Private G.L. Lacozi, 3rd Louisiana Infantry. Whether the caps were made in Tennessee, Arkansas or Louisiana, or even elsewhere, is uncertain. They are, nonetheless, representative of the type. There are also numerous surviving images of soldiers wearing this style of cap from throughout the region. The Nashville and New Orleans manufacturing hubs shut down upon federal occupation in early 1862, and their production was shifted to the interior of Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia.

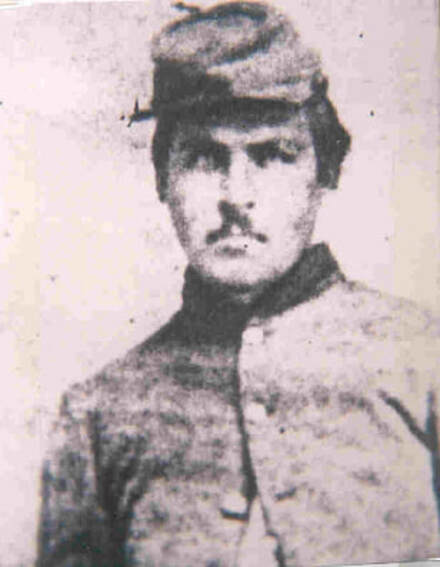

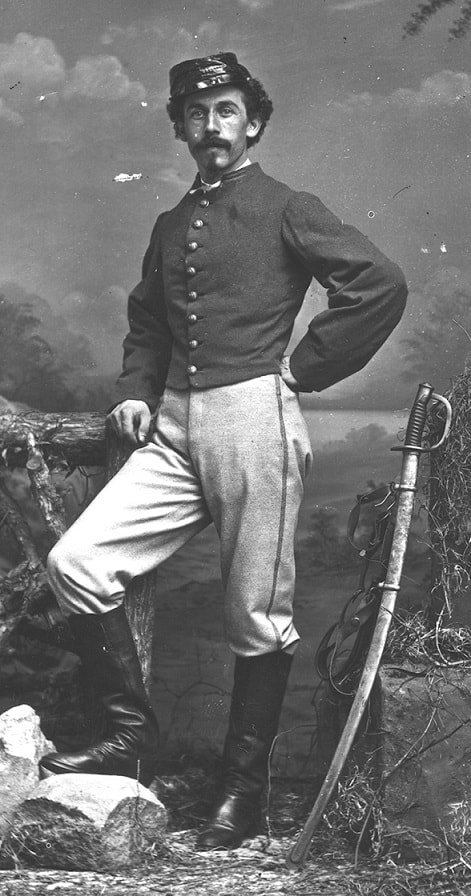

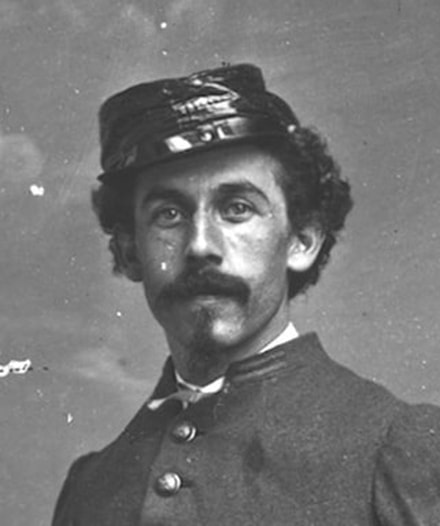

062a This unidentified member of the New Orleans, Crescent City Guards (Company A, 5th Louisiana Infantry) wears a fine quality cap with a dark, presumably black band. The soldier cocked his cap to the right in typical Confederate fashion. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Liljenquist collection, 32588u.

Atlanta-Columbus Depot Caps

Next to the Army of Northern Virginia, the Army of Tennessee was the Confederacy’s largest army. Just as the primary supply base for Lee’s army was Richmond, the vast network of logistics in Georgia’s Atlanta-Columbus axis supplied Braxton Bragg’s “Western Army.” The Atlanta-Columbus clothing depots cooperated to standardize their uniforms, much as Richmond did, and their production output together was the largest of all the quartermaster operations in the Western theater. Regrettably, it is difficult to accurately identify a bonafide, Atlanta-Columbus cap, because so many different depots issued headgear in the Western theater. This makes it nearly impossible to pinpoint the origin of a given, original cap, and leads to some speculation. There is, however, one identifiable typology observed in four surviving Confederate caps, all of which have strong provenance to Georgia and the Army of Tennessee. Among other surviving original, Western theater caps, all are one-of-a-kind. One might presume that the largest depot (Atlanta-Columbus) would have left the most surviving caps, and thus ascribe these four caps to the Atlanta-Columbus Depot. Another factor that strengthens this assumption is that the basic cloth used to make the four caps in question matches that of the well-documented Atlanta-Columbus jackets. The basic uniform cloth associated with the Atlanta-Columbus jackets and caps is a cassimere or jeans with two woolen weft yarns over one cotton warp yarn. Furthermore, the red woolen, flannel trim cloth of the one Atlanta-Columbus caps, with a colored band, matches the red woolen, flannel trim cloth of the one surviving Atlanta-Columbus artillery jacket. This similarity strengthens the provenance between the artillery cap and the Atlanta-Columbus Depot.[59] The colored band of the original cap, the presence of trim colors on jackets, along with contemporary images of similar caps, indicates that the Atlanta-Columbus Depot made a percentage of its caps trimmed in the blue and red colors of the infantry and artillery.

The region of the Western Confederacy, an area encompassing Georgia and taking in all the territory westwards to the Mississippi River, may have been too vast to facilitate complete standardization of uniforms, but the region’s depots all made the chasseur-style cap. Furthermore, there appears to have been some standardization in visor production. Judging from the similarity of most Western theater visors, there appear to have been fewer visor makers than cap makers. Apparently, each visor maker supplied several depots. Captain Francis W. Dillard, the Columbus Depot quartermaster, left invoices for both caps and various cap components for the years 1863 and 1864. From these accounts offer a glimpse at how the caps were made, the materials used and the terminology involved.

The Columbus Depot caps are described as “Jeans Caps,” “Cassimere Caps” and “Kersey Caps.” The only instance where a color is mentioned is when an invoice carried the entry “Grey Jeans Caps.” The jeans and cassimere caps predominated by far. Aside from invoices for completed caps, Dillard purchased cap components to include visors, crowns, strips (without definition, presumably either chinstraps or band linings), pasteboard bands (for interlining), oil cloths, buttons, and cassimere and jeans cloth. From these invoices we know that pre-cut sets of unfinished caps included not only the pre-cut basic cloth components and lining, but all of the other pre-manufactured components, as well. From the originals, it is clear that the pasteboard-stiffened, enamel cloth visors were machine-made. This explains why visor making was specialized and why several depots might rely on a single visor manufacturer. Interestingly, S.D. Thom had a contract with the depot in April 1864 to overhaul and repair 3,025 caps, and to take off, restore and reset the visors of 1,787 caps. This comes as little surprise, considering that visors were frequently attached in a flimsy manner. In any case, the surviving invoices show that eighteen contractors supplied the depot with 91,293 caps, 150,979 visors and numerous other cap components in 1863 and 1864 alone.[60]

Numerous contemporary descriptions document the issue of gray caps from the Columbus Depot, along with the well-known Atlanta-Columbus jackets and pants. Three German-Texans serving in Waul’s Texas Legion, a soldier with Nelson’s Tennessee Artillery, as well as a Tennessee surgeon serving in Tilghman’s Division described their newly issued uniforms in October and November 1862 in Mississippi. The artilleryman was stationed at Port Hudson, while the Texas Legion and Tilghman’s Division were at Holly, Mississippi. Regardless, the entire commands received gray jackets with blue collars and cuffs, sky blue pants and gray caps.[61] Other commands described their Columbus Depot uniforms with caps, too. The 1st Missouri Brigade was entirely outfitted in this uniform in January 1863, near Grenada, Mississippi, described as, “Grey Pants, grey Jackets & grey Caps. The collars & cuffs of the Jackets are trimed [sic] with light blue.”[62] Later in 1863, a soldier in the 4th Florida wrote about this uniform in October and November while encamped near Chattanooga, describing the jackets and pants of either light or dark gray cassimere/jeans, the jackets having “mostly” blue collar and cuffs and being “superior army goods.” His described the caps that came with these uniforms merely as “miserable,” but one might infer that the caps were likewise gray in color.[63]

Dillard managed the Columbus Depot from August 1861 to the end of the war, by which time, he had been promoted to major. From October 1, 1861 to May 1864, his depot made (or acquired) 122,441 caps (approximately 3,826 caps per month).[64] Interestingly, when the Federal cavalry laid waste to the Confederate factories in Columbus on April 16, 1865, the clothing depot’s records indicated that there were 650 gray caps in stock: the last, contemporary description of the Columbus cap.[65]

One report that gives an idea of how many caps were issued from the Atlanta-Columbus quartermaster operation is field issue report for the Army of Tennessee from July 1, 1864 to January 1, 1865. It did not include issues to men in hospitals, on furlough, detailed at the posts, to officers, or to men who were paroled, exchanged or retired, which would have increased the total significantly. The field issues of headgear for this period amounted to 45,853 hats and caps. These issues were made chiefly from the three large Georgia depots: Atlanta, Columbus and Augusta. During this period, much of Augusta’s inventory had been transferred from Atlanta, so it is likely that almost all of the caps reported would have been the Atlanta-Columbus style.[66]

There are four surviving Atlanta-Columbus Depot caps, all with strong provenance. In all four cases, the provenance can be traced to the Atlanta-Columbus Depot.

Regarding the cap itself, these caps also share the characteristics common to the typology, with the tailoring and materials in each cap being consistent. The Atlanta-Columbus cap’s salient feature is the lack of a separate band piece. The sides form the base of the cap, exactly like the Union forage cap. As such, the body consisted only of two side pieces and a crown. Otherwise, the cap conforms to the chasseur style with a countersunk crown. The average dimensions include the sides being three inches high in front to the fold, 6 ¾ inches high in the rear to the fold, 4 ¼ inch diameter of the crown inside the fold line in both directions, and 5 1/8 inch diameter of the crown including the folded edges all around.

The sides and crown are made of cassimere fabric, now of a tan color. The weave consists of the warp over one and under two woolen weft yarn, and the weft over two and under one warp yarn. The cotton warp color varies from tan to medium brown, but the woolen weft is consistently a natural white color. The original weft color is a matter of speculation. It appears to be a natural white color, but may have faded from a dyed, gray color. It is unusual, and noteworthy that the pieces are joined with the warp running side-to-side and the weft running top-to-bottom.

The linings are mostly unbleached, natural white osnaburg, although one of these may be nankeen brown in color. One of the caps has a white, polished cotton lining. In two of the caps, the base stiffening is visible. In both cases, the stiffening consists of a pasteboard welt placed between the basic cloth and the lining. Presumably, all Atlanta-Columbus caps were made with such stiffeners.

The visor, the one-piece, non-functional chinstrap, and the sweatband components are all of enameled cloth. The visor was made of pasteboard covered with enameled cloth and reinforced with an enamel welt. The visor has a distinctive pattern, and all of the visors have machine-stitched welts around the outside edge. The Bowman cap visor includes the following dimensions: 6 ¼ inches long, side to side, across the ends; 6 3/8 inches long, side to side, across the middle; 4 5/16 inches wide, front to rear from the front edge to the line between the ends; and 2 inches wide, front to rear, in the center from the front edge to the seam line. It is about 1/8 inch thick. The welt along the outside of the pasteboard visor is ¾ to 13/16 inches wide. The visor was whip stitched to the front on the cap.

The enamel cloth sweatband, which varied in width, was usually sewn with a seam at the base, with the tops of the components facing together; then the sweatband was turned inward to the inside, over the lining. No additional whip stitching was added to the base, nor was the top of the sweatband stitched to lining to hold it in place. The one-piece, non-functional, enameled cloth chinstrap was a half-inch to 5/8-inch wide. It was secured to the base with non-military buttons. The ends of the chinstrap were cut with either a point or with a slightly rounded edge. A unique feature of the chinstrap was its excessive length, that extended approximately a half inch behind the buttons.

Two of the original caps have colored bands. In each case, the body of the cap was completely finished, the band piece was applied around the base and the visor was then attached to the front of the cap. In so doing, the stitching was made through the pasteboard stiffening and the sweatband, without attempting to conceal the stitches. In the case of the Cicero Bowman cap, the red flannel band was whip stitched entirely around the base. In the case of the Fountain Earle cap, a strip of black velvet was whip stitched along the rear of the base ending at the chinstrap buttons.

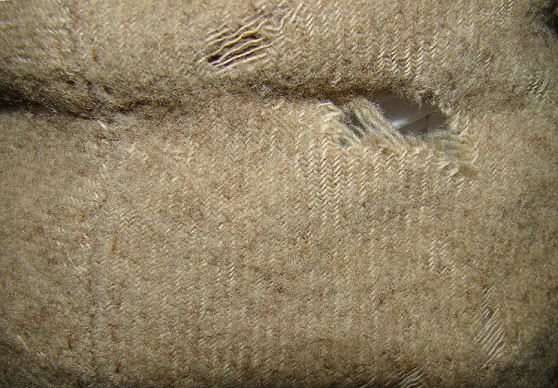

Describing the surviving caps in chronological order, the first cap belonged to Captain Fountain R. Earle, Company B, 34th Arkansas Infantry. The cap bears the marks of a near miss at the Battle of Prairie Grove on 7 December 1862. During that fight, a Minie ball passed completely through the back of the cap, scraping Earle’s scalp, but doing him no further injury. Earle took the cap off, looked at the holes and remarked, “That was a pretty close clipping.” Someone retorted that had the bullet had been an inch closer, he would have been killed. Earle replied that if it had been an inch the other direction, it would have missed him entirely.[67]

Earle’s cap was part of a consignment of clothing sent from the Columbus, Georgia Depot to Arkansas in September 1862. It is remarkable that of all the caps to survive from the Trans-Mississippi Department, the honor goes to an Atlanta-Columbus Depot cap.

The Earle cap’s basic cloth is cassimere, its weave consisting of a weft yarn that passes over two and under one warp yarn, and the warp that passes under two and over one weft yarn. The warp thread is a fine weave, cotton of a light, golden brown color, and a coarse weave woolen weft of an oatmeal-white color. The overall appearance of the cloth is a tan color. Judging from a section of protected fabric on the cap’s crown, underneath the attached fold, the fabric was originally white in color, with clean white warp and weft yarns. Perhaps the exposed surface of the cassimere takes its tan color from soiling.

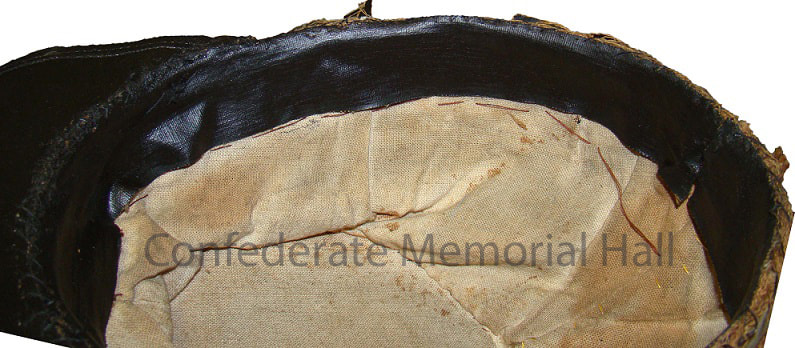

The cap is lined with unbleached white, polished cotton. The enamel cloth sweatband is sewn in the typical fashion, but the exposed width is one and a half inches wide, as opposed to the narrower, 7/8” wide sweatbands found in the other caps. Under the sweatband is the lining, and between the lining and cassimere is the pasteboard stiffener: 1 3/8 inches wide.

The visor’s dimensions approximate those of the Bowman. The dimension across the ends of the visor is 6 5/8 inches; the width across the front of the cap, side to side, is 6 9/16 inches; the depth of the visor from the middle of the front edge to the front seam line is 1 13/16 inches; the total length of the visor, from the front edge to the line, between the two end points, is 4 11/16 inches; and, the welt around the outer edge is approximately ¾ inches wide. The visor is about 1/8 inch thick. The visor is whip stitched to the front on the cap straight through the sweatband, reflective of the body of the cap having been completed before attaching the visor.

The one-piece, non-functioning chinstrap is intact, and the ends are cut with a slightly rounded edge. The buttons have shanks and are made of newsprint, paper mache. These are covered with a lightweight, dark blue flannel fabric that has been glued to the surface of the buttons. The chinstrap is 5/8 inches wide and the ends extend beyond the buttons about a half inch. As previously alluded to, the cap has a band piece that extends partially around the rear portion of the base. The band piece terminates at the point where the buttons are attached to the cap. The black velvet band is made without a seam, is whip stitched in place and matches the width of the chinstrap, being 5/8 inches wide. The use of black velvet mirrors the common use of black trim material early in the war by the Confederate quartermaster, since this color was readily available and served as a type of universal trim color.

Next to the Army of Northern Virginia, the Army of Tennessee was the Confederacy’s largest army. Just as the primary supply base for Lee’s army was Richmond, the vast network of logistics in Georgia’s Atlanta-Columbus axis supplied Braxton Bragg’s “Western Army.” The Atlanta-Columbus clothing depots cooperated to standardize their uniforms, much as Richmond did, and their production output together was the largest of all the quartermaster operations in the Western theater. Regrettably, it is difficult to accurately identify a bonafide, Atlanta-Columbus cap, because so many different depots issued headgear in the Western theater. This makes it nearly impossible to pinpoint the origin of a given, original cap, and leads to some speculation. There is, however, one identifiable typology observed in four surviving Confederate caps, all of which have strong provenance to Georgia and the Army of Tennessee. Among other surviving original, Western theater caps, all are one-of-a-kind. One might presume that the largest depot (Atlanta-Columbus) would have left the most surviving caps, and thus ascribe these four caps to the Atlanta-Columbus Depot. Another factor that strengthens this assumption is that the basic cloth used to make the four caps in question matches that of the well-documented Atlanta-Columbus jackets. The basic uniform cloth associated with the Atlanta-Columbus jackets and caps is a cassimere or jeans with two woolen weft yarns over one cotton warp yarn. Furthermore, the red woolen, flannel trim cloth of the one Atlanta-Columbus caps, with a colored band, matches the red woolen, flannel trim cloth of the one surviving Atlanta-Columbus artillery jacket. This similarity strengthens the provenance between the artillery cap and the Atlanta-Columbus Depot.[59] The colored band of the original cap, the presence of trim colors on jackets, along with contemporary images of similar caps, indicates that the Atlanta-Columbus Depot made a percentage of its caps trimmed in the blue and red colors of the infantry and artillery.

The region of the Western Confederacy, an area encompassing Georgia and taking in all the territory westwards to the Mississippi River, may have been too vast to facilitate complete standardization of uniforms, but the region’s depots all made the chasseur-style cap. Furthermore, there appears to have been some standardization in visor production. Judging from the similarity of most Western theater visors, there appear to have been fewer visor makers than cap makers. Apparently, each visor maker supplied several depots. Captain Francis W. Dillard, the Columbus Depot quartermaster, left invoices for both caps and various cap components for the years 1863 and 1864. From these accounts offer a glimpse at how the caps were made, the materials used and the terminology involved.

The Columbus Depot caps are described as “Jeans Caps,” “Cassimere Caps” and “Kersey Caps.” The only instance where a color is mentioned is when an invoice carried the entry “Grey Jeans Caps.” The jeans and cassimere caps predominated by far. Aside from invoices for completed caps, Dillard purchased cap components to include visors, crowns, strips (without definition, presumably either chinstraps or band linings), pasteboard bands (for interlining), oil cloths, buttons, and cassimere and jeans cloth. From these invoices we know that pre-cut sets of unfinished caps included not only the pre-cut basic cloth components and lining, but all of the other pre-manufactured components, as well. From the originals, it is clear that the pasteboard-stiffened, enamel cloth visors were machine-made. This explains why visor making was specialized and why several depots might rely on a single visor manufacturer. Interestingly, S.D. Thom had a contract with the depot in April 1864 to overhaul and repair 3,025 caps, and to take off, restore and reset the visors of 1,787 caps. This comes as little surprise, considering that visors were frequently attached in a flimsy manner. In any case, the surviving invoices show that eighteen contractors supplied the depot with 91,293 caps, 150,979 visors and numerous other cap components in 1863 and 1864 alone.[60]

Numerous contemporary descriptions document the issue of gray caps from the Columbus Depot, along with the well-known Atlanta-Columbus jackets and pants. Three German-Texans serving in Waul’s Texas Legion, a soldier with Nelson’s Tennessee Artillery, as well as a Tennessee surgeon serving in Tilghman’s Division described their newly issued uniforms in October and November 1862 in Mississippi. The artilleryman was stationed at Port Hudson, while the Texas Legion and Tilghman’s Division were at Holly, Mississippi. Regardless, the entire commands received gray jackets with blue collars and cuffs, sky blue pants and gray caps.[61] Other commands described their Columbus Depot uniforms with caps, too. The 1st Missouri Brigade was entirely outfitted in this uniform in January 1863, near Grenada, Mississippi, described as, “Grey Pants, grey Jackets & grey Caps. The collars & cuffs of the Jackets are trimed [sic] with light blue.”[62] Later in 1863, a soldier in the 4th Florida wrote about this uniform in October and November while encamped near Chattanooga, describing the jackets and pants of either light or dark gray cassimere/jeans, the jackets having “mostly” blue collar and cuffs and being “superior army goods.” His described the caps that came with these uniforms merely as “miserable,” but one might infer that the caps were likewise gray in color.[63]

Dillard managed the Columbus Depot from August 1861 to the end of the war, by which time, he had been promoted to major. From October 1, 1861 to May 1864, his depot made (or acquired) 122,441 caps (approximately 3,826 caps per month).[64] Interestingly, when the Federal cavalry laid waste to the Confederate factories in Columbus on April 16, 1865, the clothing depot’s records indicated that there were 650 gray caps in stock: the last, contemporary description of the Columbus cap.[65]

One report that gives an idea of how many caps were issued from the Atlanta-Columbus quartermaster operation is field issue report for the Army of Tennessee from July 1, 1864 to January 1, 1865. It did not include issues to men in hospitals, on furlough, detailed at the posts, to officers, or to men who were paroled, exchanged or retired, which would have increased the total significantly. The field issues of headgear for this period amounted to 45,853 hats and caps. These issues were made chiefly from the three large Georgia depots: Atlanta, Columbus and Augusta. During this period, much of Augusta’s inventory had been transferred from Atlanta, so it is likely that almost all of the caps reported would have been the Atlanta-Columbus style.[66]

There are four surviving Atlanta-Columbus Depot caps, all with strong provenance. In all four cases, the provenance can be traced to the Atlanta-Columbus Depot.

Regarding the cap itself, these caps also share the characteristics common to the typology, with the tailoring and materials in each cap being consistent. The Atlanta-Columbus cap’s salient feature is the lack of a separate band piece. The sides form the base of the cap, exactly like the Union forage cap. As such, the body consisted only of two side pieces and a crown. Otherwise, the cap conforms to the chasseur style with a countersunk crown. The average dimensions include the sides being three inches high in front to the fold, 6 ¾ inches high in the rear to the fold, 4 ¼ inch diameter of the crown inside the fold line in both directions, and 5 1/8 inch diameter of the crown including the folded edges all around.

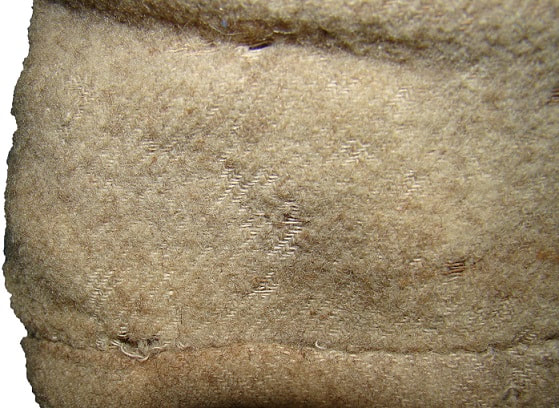

The sides and crown are made of cassimere fabric, now of a tan color. The weave consists of the warp over one and under two woolen weft yarn, and the weft over two and under one warp yarn. The cotton warp color varies from tan to medium brown, but the woolen weft is consistently a natural white color. The original weft color is a matter of speculation. It appears to be a natural white color, but may have faded from a dyed, gray color. It is unusual, and noteworthy that the pieces are joined with the warp running side-to-side and the weft running top-to-bottom.

The linings are mostly unbleached, natural white osnaburg, although one of these may be nankeen brown in color. One of the caps has a white, polished cotton lining. In two of the caps, the base stiffening is visible. In both cases, the stiffening consists of a pasteboard welt placed between the basic cloth and the lining. Presumably, all Atlanta-Columbus caps were made with such stiffeners.

The visor, the one-piece, non-functional chinstrap, and the sweatband components are all of enameled cloth. The visor was made of pasteboard covered with enameled cloth and reinforced with an enamel welt. The visor has a distinctive pattern, and all of the visors have machine-stitched welts around the outside edge. The Bowman cap visor includes the following dimensions: 6 ¼ inches long, side to side, across the ends; 6 3/8 inches long, side to side, across the middle; 4 5/16 inches wide, front to rear from the front edge to the line between the ends; and 2 inches wide, front to rear, in the center from the front edge to the seam line. It is about 1/8 inch thick. The welt along the outside of the pasteboard visor is ¾ to 13/16 inches wide. The visor was whip stitched to the front on the cap.

The enamel cloth sweatband, which varied in width, was usually sewn with a seam at the base, with the tops of the components facing together; then the sweatband was turned inward to the inside, over the lining. No additional whip stitching was added to the base, nor was the top of the sweatband stitched to lining to hold it in place. The one-piece, non-functional, enameled cloth chinstrap was a half-inch to 5/8-inch wide. It was secured to the base with non-military buttons. The ends of the chinstrap were cut with either a point or with a slightly rounded edge. A unique feature of the chinstrap was its excessive length, that extended approximately a half inch behind the buttons.

Two of the original caps have colored bands. In each case, the body of the cap was completely finished, the band piece was applied around the base and the visor was then attached to the front of the cap. In so doing, the stitching was made through the pasteboard stiffening and the sweatband, without attempting to conceal the stitches. In the case of the Cicero Bowman cap, the red flannel band was whip stitched entirely around the base. In the case of the Fountain Earle cap, a strip of black velvet was whip stitched along the rear of the base ending at the chinstrap buttons.

Describing the surviving caps in chronological order, the first cap belonged to Captain Fountain R. Earle, Company B, 34th Arkansas Infantry. The cap bears the marks of a near miss at the Battle of Prairie Grove on 7 December 1862. During that fight, a Minie ball passed completely through the back of the cap, scraping Earle’s scalp, but doing him no further injury. Earle took the cap off, looked at the holes and remarked, “That was a pretty close clipping.” Someone retorted that had the bullet had been an inch closer, he would have been killed. Earle replied that if it had been an inch the other direction, it would have missed him entirely.[67]

Earle’s cap was part of a consignment of clothing sent from the Columbus, Georgia Depot to Arkansas in September 1862. It is remarkable that of all the caps to survive from the Trans-Mississippi Department, the honor goes to an Atlanta-Columbus Depot cap.

The Earle cap’s basic cloth is cassimere, its weave consisting of a weft yarn that passes over two and under one warp yarn, and the warp that passes under two and over one weft yarn. The warp thread is a fine weave, cotton of a light, golden brown color, and a coarse weave woolen weft of an oatmeal-white color. The overall appearance of the cloth is a tan color. Judging from a section of protected fabric on the cap’s crown, underneath the attached fold, the fabric was originally white in color, with clean white warp and weft yarns. Perhaps the exposed surface of the cassimere takes its tan color from soiling.

The cap is lined with unbleached white, polished cotton. The enamel cloth sweatband is sewn in the typical fashion, but the exposed width is one and a half inches wide, as opposed to the narrower, 7/8” wide sweatbands found in the other caps. Under the sweatband is the lining, and between the lining and cassimere is the pasteboard stiffener: 1 3/8 inches wide.

The visor’s dimensions approximate those of the Bowman. The dimension across the ends of the visor is 6 5/8 inches; the width across the front of the cap, side to side, is 6 9/16 inches; the depth of the visor from the middle of the front edge to the front seam line is 1 13/16 inches; the total length of the visor, from the front edge to the line, between the two end points, is 4 11/16 inches; and, the welt around the outer edge is approximately ¾ inches wide. The visor is about 1/8 inch thick. The visor is whip stitched to the front on the cap straight through the sweatband, reflective of the body of the cap having been completed before attaching the visor.

The one-piece, non-functioning chinstrap is intact, and the ends are cut with a slightly rounded edge. The buttons have shanks and are made of newsprint, paper mache. These are covered with a lightweight, dark blue flannel fabric that has been glued to the surface of the buttons. The chinstrap is 5/8 inches wide and the ends extend beyond the buttons about a half inch. As previously alluded to, the cap has a band piece that extends partially around the rear portion of the base. The band piece terminates at the point where the buttons are attached to the cap. The black velvet band is made without a seam, is whip stitched in place and matches the width of the chinstrap, being 5/8 inches wide. The use of black velvet mirrors the common use of black trim material early in the war by the Confederate quartermaster, since this color was readily available and served as a type of universal trim color.

The second Atlanta-Columbus cap was worn by Private Cicero Bowman, who served with Company A, 5th Georgia Reserves during April and May 1863. His company was part of Captain C.D. Findlay’s Ordnance Guard at Macon, Georgia. The seventeen-year-old had enlisted for the war on April 2, 1863 under the name, C. Bowman. Bowman’s cap is distinct in that it has a one-inch wide, red band around the base, albeit very moth-eaten with only remnants along its top and bottom edges. Findlay’s Company probably drew red-trimmed caps to indicate their affiliation with the ordnance branch. In any case, Bowman’s cap represents a trimmed variant of the Atlanta-Columbus cap, which suggests that there were more of this type made with colored blue and red bands. The band was added after the body of the cap was completed and before the visor was attached.

The coloration, weave, warp and weft of the basic cloth of Bowman’s cap, and the grainline of the construction, matches the other Atlanta-Columbus caps. The osnaburg lining appears to have a tan color, but this may reflect some soiling rather than its original color. The sweatband is likewise sewn in the manner of the other Atlanta-Columbus caps, although the seamstress took care not to sew the visor stitches through the sweatband. Interestingly, the seam of the sweatband is placed at the front of the cap, next to visor instead of placing it at the rear of the cap, near the rear seam. The band stiffener is not visible in this artifact. The chinstrap and buttons are missing.[68]

The coloration, weave, warp and weft of the basic cloth of Bowman’s cap, and the grainline of the construction, matches the other Atlanta-Columbus caps. The osnaburg lining appears to have a tan color, but this may reflect some soiling rather than its original color. The sweatband is likewise sewn in the manner of the other Atlanta-Columbus caps, although the seamstress took care not to sew the visor stitches through the sweatband. Interestingly, the seam of the sweatband is placed at the front of the cap, next to visor instead of placing it at the rear of the cap, near the rear seam. The band stiffener is not visible in this artifact. The chinstrap and buttons are missing.[68]

The third of these caps was worn by 1st Sergeant David Jacob Inabinet, Company B, 20th South Carolina Infantry. Inabinet’s command was assigned to the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida from 1861 to the spring 1864. In the spring of 1864, it moved to Virginia and fought at the Battle of Cold Harbor. The regiment next participated in General Early’s Valley Campaign in the summer of 1864, and ended the war in North Carolina, where it fought at Bentonville in 1865. Inabinet probably drew this cap, along with other quartermaster clothing, while he was at home in Orangeburg, South Carolina on convalescence furlough, sometime after August 31, 1864. He remained on furlough for an unspecified period, and had a good opportunity to draw from stocks that had been relocated to the Augusta area from the Atlanta-Columbus operation that summer.

Inabinet’s cap matches the others of the type closely in all respects. Only its cotton warp is darker that the rest, being a medium brown color. The osnaburg lining is also a darker tan color than observed in the Bowman cap, and it may be the natural color of nankeen cotton. The chinstrap is secured with two, half-inch, white bone buttons that are covered with lightweight black flannel. The ends of the chinstrap are cut with a point and nearly an inch of slack protrudes behind the button on either side. The paste board stiffener is visible through a damaged section of the base. The Inabinet cap represents the typical, plain version, Atlanta-Columbus cap, devoid of trim cloth, and useful as a general service cap for all branches.[69]

Inabinet’s cap matches the others of the type closely in all respects. Only its cotton warp is darker that the rest, being a medium brown color. The osnaburg lining is also a darker tan color than observed in the Bowman cap, and it may be the natural color of nankeen cotton. The chinstrap is secured with two, half-inch, white bone buttons that are covered with lightweight black flannel. The ends of the chinstrap are cut with a point and nearly an inch of slack protrudes behind the button on either side. The paste board stiffener is visible through a damaged section of the base. The Inabinet cap represents the typical, plain version, Atlanta-Columbus cap, devoid of trim cloth, and useful as a general service cap for all branches.[69]

065n: This close up image of the inside shows the weave and texture of the nankeen cotton, osnaburg lining. It also shows the absence of whip stitching along the base of the sweatband. Instead, the sweatband is secured to the lining with a basted stitch along its top edge. An interior view shows the nankeen cotton lining, similar to that observed in the Bowman cap, and the underside of the visor. Artifact courtesy of South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina.

The fourth, and last Atlanta-Columbus cap was worn by Lieutenant Colonel Columbus M. Sykes, Commander of the 43rd Mississippi Infantry. Sykes died in Northern Mississippi in January 1865. Shortly after his command’s return from the Army of Tennessee’s disastrous Nashville Campaign, a tree fell on him while he was sleeping, killing him. Prior to his demise, Sykes acquired and wore this enlisted cap, a practice fairly common among officers in the Western theater. In all likelihood, Sykes obtained the cap before the Tennessee Campaign, while his command was still being supplied out of Georgia.

Syke’s cap is almost identical to Inabinet’s, being a general service variant devoid of trim. Syke’s cap is noted as being a small size, about 6 ¾ or 6 7/8. The cotton warp is light brown, and the other characteristics conform to the other three Atlanta-Columbus caps. The enamel sweatband is whipstitched around the base, but this may have been done by a conservator. The osnaburg lining is unbleached and natural white in color. The chinstrap was secured in place with two leather, two-hole buttons, of which only one remains intact. The ends of the chinstrap are cut nearly straight, but with a slight curve, and characteristic of the type, the ends of the chinstrap have about a half inch of slack that sticks out behind the button. The pasteboard stiffener is visible at the base of the cap through the damaged sections of the basic cloth.[70]

Syke’s cap is almost identical to Inabinet’s, being a general service variant devoid of trim. Syke’s cap is noted as being a small size, about 6 ¾ or 6 7/8. The cotton warp is light brown, and the other characteristics conform to the other three Atlanta-Columbus caps. The enamel sweatband is whipstitched around the base, but this may have been done by a conservator. The osnaburg lining is unbleached and natural white in color. The chinstrap was secured in place with two leather, two-hole buttons, of which only one remains intact. The ends of the chinstrap are cut nearly straight, but with a slight curve, and characteristic of the type, the ends of the chinstrap have about a half inch of slack that sticks out behind the button. The pasteboard stiffener is visible at the base of the cap through the damaged sections of the basic cloth.[70]

In addition to the original caps, there are contemporary descriptions and images with sound provenance to Columbus, Georgia, and the Atlanta-Columbus clothing operation. These latter sources suggest that most of the Atlanta-Columbus caps were made in plain gray: a universal cap, usable by all branches of the service, such as the Richmond Depot produced. A lesser percentage was made in the 1861 style, with either red or dark blue bands. All the available evidence indicates that the caps were made of domestic fabrics: either cassimere or jeans.

Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida Caps

Some of the earliest clothing manufacturing in the Charleston area was organized by the State of South Carolina. The state’s quartermaster operation provided clothing to South Carolina soldiers before the Confederate quartermaster became fully functional, largely by contract. The hatter company, Williams and Brown in Charleston furnished the military with gray or blue chasseur style caps (presumably to the state quartermaster).[71] Between 1 January and 30 August 1862, the South Carolina Quartermaster Department had purchased, manufactured and received 2,545 hats and 2,430 caps.[72] By 28 October 1862, the state quartermaster had transferred much of its clothing stores to Colonel Samuel McGowan, the Confederate Quartermaster in Charleston, indicative of a transition to a centralized, Confederate operation. Interestingly, the state quartermaster did not turn over its remaining 665 caps to the Confederate quartermaster, for reasons unknown.[73]

By 1863, the Confederate Quartermaster in Charleston, Captain George J. Crafts, was manufacturing clothing, using both imported and domestic fabrics, and transferred 486 caps on 7 February 1863.[74] Nonetheless, the quartermaster continued to purchase clothing from contractors, most notably Charles F. Jackson’s manufacturing company in Columbia, South Carolina. From June 1863 to November 1864, Jackson provided the Confederate quartermaster with 12,294 caps.[75] All in all, six cap making companies provided caps to the departmental quartermaster, between November 1861 and December 1864. The Charleston quartermaster purchased a total of 43,477 caps, while Major L.O. Bridewell, in charge of the clothing bureau for the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, received 5,146 caps at Augusta, Georgia. The appearance of these caps was described as follows: “Grey Caps and Grey Cloth Caps,” “Blue Caps and Blue Cloth Caps,” “Glazed Caps,” “Caps with Covers,” “Grey Beauregard Caps,” “Caps Red Bands,” and “Blue Caps, Cavalry.” Regarding the materials used to make them, are descriptions of “Kersey Caps,” “Jeans Caps,” “Caps with Leather Fronts” and “Caps with Cloth Fronts (the visor being covered with enameled cloth).” Accessories and components included “Glazed Cap Covers,” “Leather Cap Fronts” and “Covered Cap Fronts” (the latter visor type being covered with enameled cloth). Interestingly, contractor Miles Johnson dyed 329 yards of drilling to use as bands for cavalry caps in July 1864.[76] The Savannah post quartermaster also described his caps similarly in his inventory which included 175 oil cloth caps and 300 gray cloth caps.[77]

Caps in the Department South Carolina, Georgia and Florida are chiefly documented through contemporary photographs and paintings. One of the Confederacy’s foremost soldier-artists, Conrad Wise Chapman, was assigned to the Charleston garrison from mid-September 1863 to early April 1864. During that time, Chapman documented the war, and coincidentally the soldiers’ uniforms, through his numerous oil paintings. Chapman was careful to paint exactly what he saw, without embellishment, and his paintings depict the troops wearing a mix of chasseur caps of steel gray, some plain and others with red bands, and the ubiquitous wool slouch hat. One painting even shows a soldier wearing an all-red cap.[78]

Some of the earliest clothing manufacturing in the Charleston area was organized by the State of South Carolina. The state’s quartermaster operation provided clothing to South Carolina soldiers before the Confederate quartermaster became fully functional, largely by contract. The hatter company, Williams and Brown in Charleston furnished the military with gray or blue chasseur style caps (presumably to the state quartermaster).[71] Between 1 January and 30 August 1862, the South Carolina Quartermaster Department had purchased, manufactured and received 2,545 hats and 2,430 caps.[72] By 28 October 1862, the state quartermaster had transferred much of its clothing stores to Colonel Samuel McGowan, the Confederate Quartermaster in Charleston, indicative of a transition to a centralized, Confederate operation. Interestingly, the state quartermaster did not turn over its remaining 665 caps to the Confederate quartermaster, for reasons unknown.[73]

By 1863, the Confederate Quartermaster in Charleston, Captain George J. Crafts, was manufacturing clothing, using both imported and domestic fabrics, and transferred 486 caps on 7 February 1863.[74] Nonetheless, the quartermaster continued to purchase clothing from contractors, most notably Charles F. Jackson’s manufacturing company in Columbia, South Carolina. From June 1863 to November 1864, Jackson provided the Confederate quartermaster with 12,294 caps.[75] All in all, six cap making companies provided caps to the departmental quartermaster, between November 1861 and December 1864. The Charleston quartermaster purchased a total of 43,477 caps, while Major L.O. Bridewell, in charge of the clothing bureau for the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, received 5,146 caps at Augusta, Georgia. The appearance of these caps was described as follows: “Grey Caps and Grey Cloth Caps,” “Blue Caps and Blue Cloth Caps,” “Glazed Caps,” “Caps with Covers,” “Grey Beauregard Caps,” “Caps Red Bands,” and “Blue Caps, Cavalry.” Regarding the materials used to make them, are descriptions of “Kersey Caps,” “Jeans Caps,” “Caps with Leather Fronts” and “Caps with Cloth Fronts (the visor being covered with enameled cloth).” Accessories and components included “Glazed Cap Covers,” “Leather Cap Fronts” and “Covered Cap Fronts” (the latter visor type being covered with enameled cloth). Interestingly, contractor Miles Johnson dyed 329 yards of drilling to use as bands for cavalry caps in July 1864.[76] The Savannah post quartermaster also described his caps similarly in his inventory which included 175 oil cloth caps and 300 gray cloth caps.[77]

Caps in the Department South Carolina, Georgia and Florida are chiefly documented through contemporary photographs and paintings. One of the Confederacy’s foremost soldier-artists, Conrad Wise Chapman, was assigned to the Charleston garrison from mid-September 1863 to early April 1864. During that time, Chapman documented the war, and coincidentally the soldiers’ uniforms, through his numerous oil paintings. Chapman was careful to paint exactly what he saw, without embellishment, and his paintings depict the troops wearing a mix of chasseur caps of steel gray, some plain and others with red bands, and the ubiquitous wool slouch hat. One painting even shows a soldier wearing an all-red cap.[78]

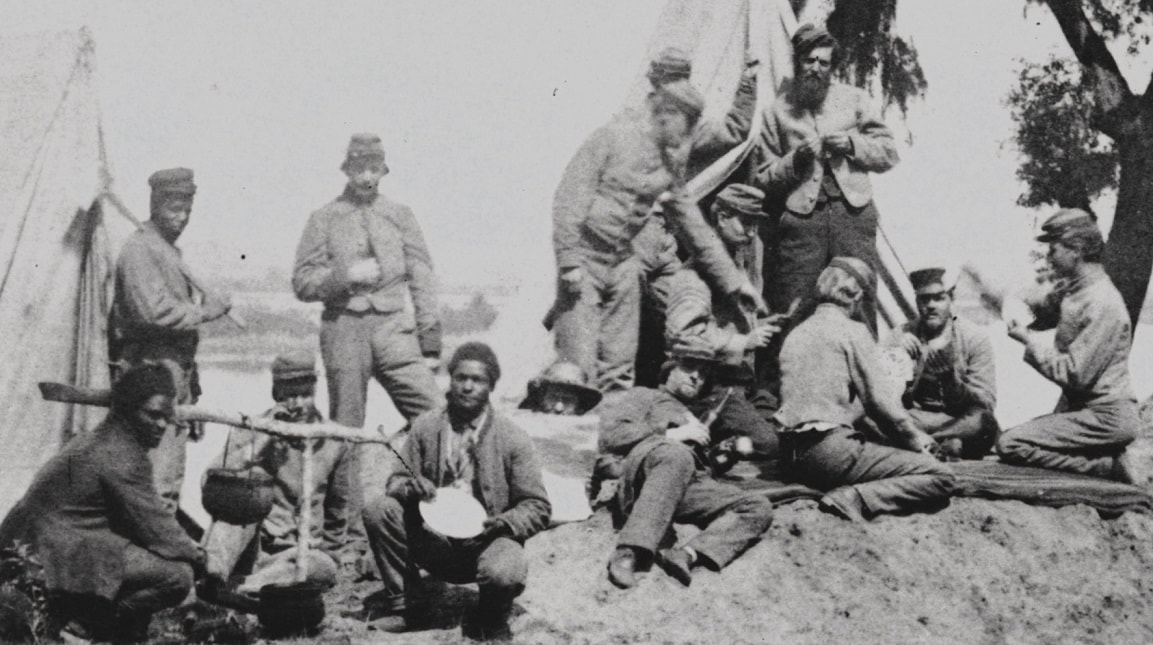

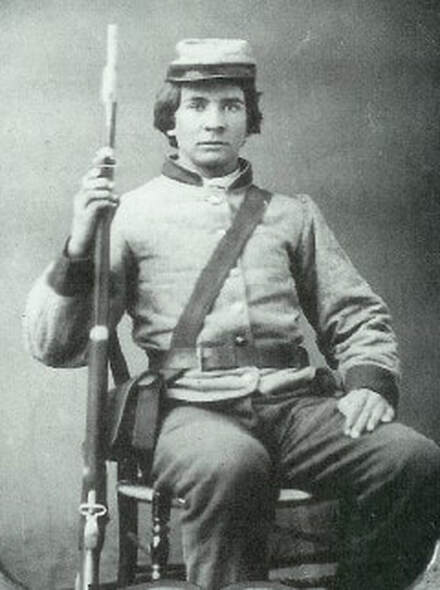

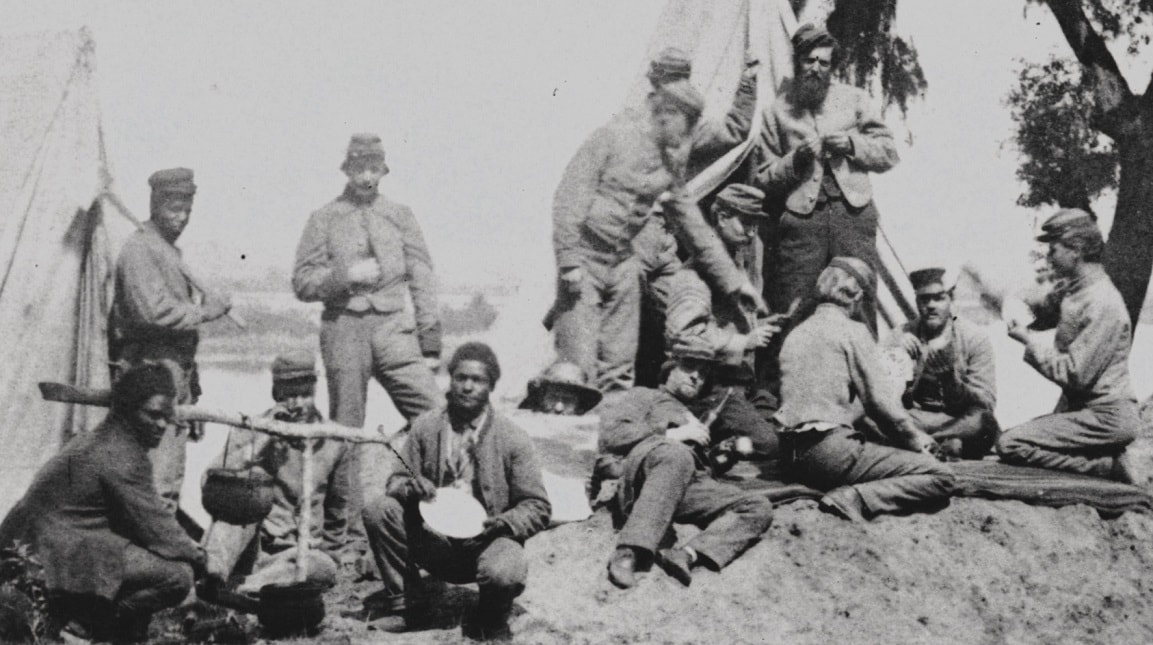

Four excellent photos document the uniform caps of the army at Charleston, as well. Two depict the South Carolina Palmetto Light Artillery Battery at the Stono River, in Charleston, both at their guns and lounging in camp. These images would have been made between March and June 1862, after the battery formed and before it departed for Virginia.[79] Another photo shows an unnamed light artillery crew practicing cannon drill in a Charleston fortification. This image was presumably taken during the same time frame that the Palmetto Light battery photos were made.[80] Most of the caps are made in the chasseur pattern, 1861 style with a red band. The sides and crown are made of the basic uniform cloth (presumably gray). However, one of the caps is made in the US army, forage cap pattern; one is a lower-sided, Confederate style forage cap (without a countersunk crown); and, one is a high-sided, “Stonewall Jackson” style cap (of a darker material than the light-colored jackets).

The last image depicts a light artillery gun crew with the caption, “Coles Island No 4.” The caption refers to the battery’s location and its position on the line. The back of the image has the inscription, “Marion Artillery of Charleston.” The inscription may have been added after the war, but the caption indicates that the gun crew is South Carolinian.[81] The entire gun crew wears caps, albeit of different styles. Four of the caps appear to be shiny, enameled cloth, of the chasseur pattern. One of these is worn with the chinstrap down. One of the caps is a light-colored, plain chasseur pattern without a colored band, worn with the chinstrap down. One is made in the high forage cap, Stonewall style (without a countersunk crown), having a crown that falls slightly forward. It is made from light-colored basic cloth, without a colored band, and worn with the chinstrap down. Two soldiers have what appear to be dark-colored Stonewall caps, and two appear to be wearing Federal, dark blue, 1858-pattern forage caps.

With all of the evidence taken into account, a variety of caps were issued in the department. These were mostly of the chasseur pattern, but some were the 1858 style. The caps came in both imported and domestic fabrics, and in varying shades, ranging from blue-gray kersey to light gray jeans. The most common variants were plain gray and 1861-style caps.

Only one enlisted cap from the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida has survived, that being Sweatman’s 1858-style forage cap. Sweatman’s cap has been described in the first part of this study. While Sweatman’s cap has impeccable provenance, it is not representative of most of the caps issued in the department. According to contemporary photographs and artwork from the region, the chasseur cap was most widespread.

Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana Depot Caps

The western most part of the Confederacy’s Western Theater was the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. By the spring of 1862, the theater’s largest manufacturing centers (New Orleans and Nashville) had fallen to Union forces, and Alabama and Mississippi re-established a logistical base within their Southern controlled territory. In 1862, this amounted to numerous small factories that pooled their production to supply the Confederate army. By 1864, some consolidation and standardization had been achieved, but from the start the many small factories produced a diverse assortment of clothing that makes it nearly impossible to categorize uniforms in a systematic typology. The few surviving caps from the region defy distinct categories since only one from any given factory might exist, and they cannot be compared or grouped with other caps.

Caps with provenance to the Lower South are found in the chasseur pattern, usually without a colored band. However, some were made with colored bands, in accordance with the 1861 regulations, as observed in contemporary images, and described in contemporary accounts. The exact origins of the surviving caps cannot be ascertained, but given the provenance, the larger quartermaster operations of Montgomery, Alabama and Columbus, Mississippi are likely sources.

As the Lower South’s logistical base shifted from Tennessee southwards, the quartermasters in Mississippi and Alabama had to rely on contractors to furnish clothing until they could establish their own government factories. Purchases of caps for the clothing bureaus in Jackson, Mississippi and for the Montgomery-Selma, Alabama operation reflect this. The Jackson quartermaster (incorporating Corinth, as well), Captain William M. Gillaspie, purchased 11,750 caps between December 1862 and May 1863. These included unspecified caps, “Grey Caps,” “Oil Cloth Caps,” “Glazed Caps” and “Kersey Caps.” He also bought visors, crowns, strips (unspecified, but perhaps enamel cloth chinstraps or pasteboard band interlining) and oil cloth.[82] Gillaspie and Captain Andrew P. Calhoun also purchased 33,188 caps for the Montgomery-Selma operation (which encompassed Mobile, as well) from May 1863 to June 1864. These were described as “Grey Cloth Caps,” “Grey Caps,” “Military Cloth Caps,” “Soldiers Caps” and “Cassimere Caps.”[83] These records indicate that cap making was a specialty that the quartermasters left largely to contractors, rather than making them in-house with their own workforce.

The next year, the Mobile Register and Advertiser lauded Major William J. Anderson’s achievements at his Columbus, Mississippi Depot in an article dated 17 May 1864. Accordingly, Anderson’s clothing depot had supplied significant quantities of clothing to the army since January 1863, to include 20,415 hats and caps. Contractors continued to furnish goods, as well. Wesson’s “Choctaw factory” supplied most of the depot’s fabrics used to make the jackets, pants and coats (jeans and linseys); and, two companies in Columbus provided Anderson with shirting, hats and caps.[84] By mid-1864, the army in Alabama and Mississippi was well supplied. General Dabney Maury’s command at Mobile received more than adequate clothing between 1 July and 30 November 1864, including 27,292 hats and caps.[85]

One surviving cap that probably came from a small factory in Georgia, Alabama or Mississippi was worn by Color Sergeant Robert Clinton Anderson, 2nd Kentucky Infantry, CSA. Anderson was wearing this cap when he was killed at Chickamauga, while fighting with the Army of Tennessee. Interestingly, General Helm, Commander of the Kentucky Brigade, had ordered the men in February 1863 to continue wearing their army wear caps on parade, carrying forward the policy of his predecessor, “Bench-leg” Hanson.[86]

The Anderson cap is made from a plain-weave fabric with a very heavy, steel gray-colored nap. The warp is a light, golden brown, and the weft is a gray woolen. Most of the nap is intact. This steel gray color remains constant inside and out, and under the seams, all these areas being exposed since the cap has no interior lining on the sides. There is no indication that the cap faded from another shade. The composition visor has a leather top and pasteboard bottom, the pasteboard layer being covered with enameled cloth. What is especially unusual is that the binding welt around the outside edge is neither enamel cloth or leather, but instead black woolen tape. The tape appears to have been machine-stitched along the top of the visor, then folded under, and whip stitched through the enamel cloth layer. The pasteboard crown has a layer of buckram or jeans cloth between it and the basic cloth on top. It had no lining inside the crown, but Anderson apparently added a piece of blue cloth to that surface himself. The sweatband and chinstrap are enameled cloth. The sweatband was joined to the band by laying the tops of the cloth band and sweatband together, stitching through and turning the sweatband inwards into the cap. The band piece has no buckram stiffening, although this may have come loose at some point. The two-piece band has seams in both the front and rear seam. The cap appears to be machine-stitched. One Federal, general service button remains in the left side of the cap. The two-piece chinstrap is in poor condition, missing its keepers, and the left piece broken, but with the fragment present. The Anderson’s salient feature is that it appears to have been intentionally made without a lining.[87]

Only one enlisted cap from the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida has survived, that being Sweatman’s 1858-style forage cap. Sweatman’s cap has been described in the first part of this study. While Sweatman’s cap has impeccable provenance, it is not representative of most of the caps issued in the department. According to contemporary photographs and artwork from the region, the chasseur cap was most widespread.

Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana Depot Caps

The western most part of the Confederacy’s Western Theater was the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. By the spring of 1862, the theater’s largest manufacturing centers (New Orleans and Nashville) had fallen to Union forces, and Alabama and Mississippi re-established a logistical base within their Southern controlled territory. In 1862, this amounted to numerous small factories that pooled their production to supply the Confederate army. By 1864, some consolidation and standardization had been achieved, but from the start the many small factories produced a diverse assortment of clothing that makes it nearly impossible to categorize uniforms in a systematic typology. The few surviving caps from the region defy distinct categories since only one from any given factory might exist, and they cannot be compared or grouped with other caps.

Caps with provenance to the Lower South are found in the chasseur pattern, usually without a colored band. However, some were made with colored bands, in accordance with the 1861 regulations, as observed in contemporary images, and described in contemporary accounts. The exact origins of the surviving caps cannot be ascertained, but given the provenance, the larger quartermaster operations of Montgomery, Alabama and Columbus, Mississippi are likely sources.

As the Lower South’s logistical base shifted from Tennessee southwards, the quartermasters in Mississippi and Alabama had to rely on contractors to furnish clothing until they could establish their own government factories. Purchases of caps for the clothing bureaus in Jackson, Mississippi and for the Montgomery-Selma, Alabama operation reflect this. The Jackson quartermaster (incorporating Corinth, as well), Captain William M. Gillaspie, purchased 11,750 caps between December 1862 and May 1863. These included unspecified caps, “Grey Caps,” “Oil Cloth Caps,” “Glazed Caps” and “Kersey Caps.” He also bought visors, crowns, strips (unspecified, but perhaps enamel cloth chinstraps or pasteboard band interlining) and oil cloth.[82] Gillaspie and Captain Andrew P. Calhoun also purchased 33,188 caps for the Montgomery-Selma operation (which encompassed Mobile, as well) from May 1863 to June 1864. These were described as “Grey Cloth Caps,” “Grey Caps,” “Military Cloth Caps,” “Soldiers Caps” and “Cassimere Caps.”[83] These records indicate that cap making was a specialty that the quartermasters left largely to contractors, rather than making them in-house with their own workforce.

The next year, the Mobile Register and Advertiser lauded Major William J. Anderson’s achievements at his Columbus, Mississippi Depot in an article dated 17 May 1864. Accordingly, Anderson’s clothing depot had supplied significant quantities of clothing to the army since January 1863, to include 20,415 hats and caps. Contractors continued to furnish goods, as well. Wesson’s “Choctaw factory” supplied most of the depot’s fabrics used to make the jackets, pants and coats (jeans and linseys); and, two companies in Columbus provided Anderson with shirting, hats and caps.[84] By mid-1864, the army in Alabama and Mississippi was well supplied. General Dabney Maury’s command at Mobile received more than adequate clothing between 1 July and 30 November 1864, including 27,292 hats and caps.[85]

One surviving cap that probably came from a small factory in Georgia, Alabama or Mississippi was worn by Color Sergeant Robert Clinton Anderson, 2nd Kentucky Infantry, CSA. Anderson was wearing this cap when he was killed at Chickamauga, while fighting with the Army of Tennessee. Interestingly, General Helm, Commander of the Kentucky Brigade, had ordered the men in February 1863 to continue wearing their army wear caps on parade, carrying forward the policy of his predecessor, “Bench-leg” Hanson.[86]

The Anderson cap is made from a plain-weave fabric with a very heavy, steel gray-colored nap. The warp is a light, golden brown, and the weft is a gray woolen. Most of the nap is intact. This steel gray color remains constant inside and out, and under the seams, all these areas being exposed since the cap has no interior lining on the sides. There is no indication that the cap faded from another shade. The composition visor has a leather top and pasteboard bottom, the pasteboard layer being covered with enameled cloth. What is especially unusual is that the binding welt around the outside edge is neither enamel cloth or leather, but instead black woolen tape. The tape appears to have been machine-stitched along the top of the visor, then folded under, and whip stitched through the enamel cloth layer. The pasteboard crown has a layer of buckram or jeans cloth between it and the basic cloth on top. It had no lining inside the crown, but Anderson apparently added a piece of blue cloth to that surface himself. The sweatband and chinstrap are enameled cloth. The sweatband was joined to the band by laying the tops of the cloth band and sweatband together, stitching through and turning the sweatband inwards into the cap. The band piece has no buckram stiffening, although this may have come loose at some point. The two-piece band has seams in both the front and rear seam. The cap appears to be machine-stitched. One Federal, general service button remains in the left side of the cap. The two-piece chinstrap is in poor condition, missing its keepers, and the left piece broken, but with the fragment present. The Anderson’s salient feature is that it appears to have been intentionally made without a lining.[87]

069n: This image shows the quarter-inch seams of the basic cloth components and the steel gray color of the woolen cloth. The blue print, cotton piece was added as a lining for the crown's inside after the cap was issued. Artifact courtesy of the Kentucky Military History Museum, Frankfort, Kentucky.

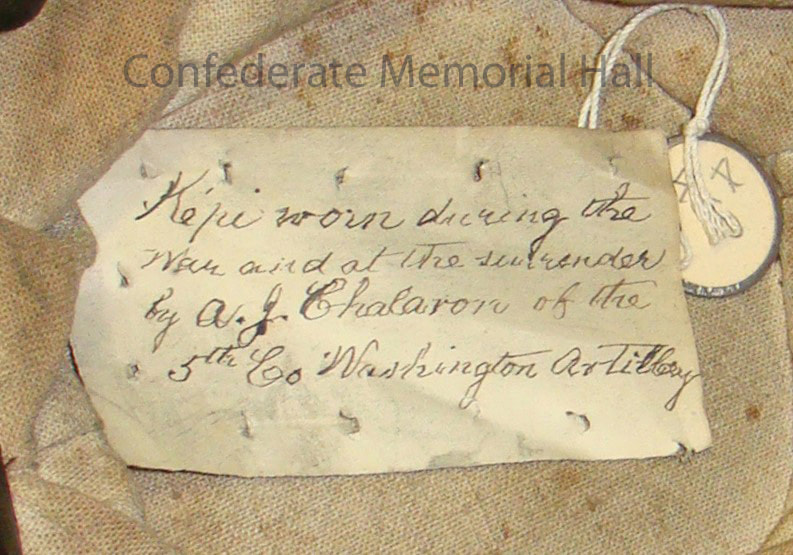

A cap with clear provenance to the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana is one worn by Lieutenant J.A. Chalaron, 5th Company, Louisiana Washington Artillery. This company fought in the Army of Tennessee, and after the Tennessee Campaign of 1864, it was assigned Mobile where it served to the end of the war. Chalaron was present at the company’s last battle at Spanish Fort, and at its surrender near Mobile in May 1865. Chalaron probably received his cap between the time his company returned from the Tennessee Campaign in December and when the army disbanded in May. Despite him being an officer, he drew an enlisted depot cap, as many officers did in the Western theater, and added a band of eighth-inch gold lace to the non-functional chinstrap to denote his rank.[88] Chalaron’s cap is accompanied by an enameled rain cover that he may have acquired privately.

The basic fabric weave is one woolen weft yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarns, and a cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen weft yarns. This matches the Montgomery jacket weave, and might suggest that the cap was made at the Montgomery Depot. The woolen fill yarn is an oatmeal or natural white color; the cotton warp is a yellowish, golden-brown color. The woolen fill yarn may have originally been dyed a gray shade, but if so, it has since faded. The yellowish-tan cotton warp yarns blending with the oatmeal-colored woolen fill yarns render a tan color to the fabric. The inner lining is an unbleached, natural white, cotton osnaburg.

Chalaron’s cap has some remarkable characteristics. Instead of a buckram stiffener in the band, this cap has a heavy pasteboard stiffener (of two pieces) that was apparently glued in place originally. The use of a pasteboard stiffener mirrors the production practice used for the Atlanta-Columbus Depot cap. Moreover, the rear seam is stiffened with a piece of bowed, river cane that extends from the fold in the crown all the way to the bottom of the band. The pasteboard visor is covered with enameled cotton drilling, and has a welt of enameled osnaburg that binds the outer edge. The welt was machine-stitched around the outer edge of the visor at ten stitches per inch. The completed visor was whipstitched to the front of the cap. The one-piece, non-functional chinstrap, cut from enameled osnaburg, is rather wide at three-quarters of an inch. The bottom edge of the chinstrap overlaps the seam of the visor, which may account for its unusual width. As alluded to previously, the chinstrap has a strand of one-eighth inch gold lace tacked along the center of its entire length. The original chinstrap buttons are missing.

The enameled osnaburg sweatband is whipstitched with close stitches to base of the cap. The bottom edge of the sweatband is unfinished. The wider stitching now present on the sweatband is restoration stitching from the 1970s. The top of the sweatband is not stitched to the lining.

The basic cloth, cap components consist of two side pieces, a separate one-piece band, and a countersunk crown piece. The inner lining consists of two side pieces and the crown, albeit the left side of the lining has been pieced together with two pieces of scrap. The crown appears to be of pasteboard. The height of the cap in front is three inches.

The enameled rain cover fits over the cap and is made with two side pieces and a crown piece. It will be described fully in Part IV.

The basic fabric weave is one woolen weft yarn over two and under one cotton warp yarns, and a cotton warp yarn under two and over one woolen weft yarns. This matches the Montgomery jacket weave, and might suggest that the cap was made at the Montgomery Depot. The woolen fill yarn is an oatmeal or natural white color; the cotton warp is a yellowish, golden-brown color. The woolen fill yarn may have originally been dyed a gray shade, but if so, it has since faded. The yellowish-tan cotton warp yarns blending with the oatmeal-colored woolen fill yarns render a tan color to the fabric. The inner lining is an unbleached, natural white, cotton osnaburg.

Chalaron’s cap has some remarkable characteristics. Instead of a buckram stiffener in the band, this cap has a heavy pasteboard stiffener (of two pieces) that was apparently glued in place originally. The use of a pasteboard stiffener mirrors the production practice used for the Atlanta-Columbus Depot cap. Moreover, the rear seam is stiffened with a piece of bowed, river cane that extends from the fold in the crown all the way to the bottom of the band. The pasteboard visor is covered with enameled cotton drilling, and has a welt of enameled osnaburg that binds the outer edge. The welt was machine-stitched around the outer edge of the visor at ten stitches per inch. The completed visor was whipstitched to the front of the cap. The one-piece, non-functional chinstrap, cut from enameled osnaburg, is rather wide at three-quarters of an inch. The bottom edge of the chinstrap overlaps the seam of the visor, which may account for its unusual width. As alluded to previously, the chinstrap has a strand of one-eighth inch gold lace tacked along the center of its entire length. The original chinstrap buttons are missing.

The enameled osnaburg sweatband is whipstitched with close stitches to base of the cap. The bottom edge of the sweatband is unfinished. The wider stitching now present on the sweatband is restoration stitching from the 1970s. The top of the sweatband is not stitched to the lining.

The basic cloth, cap components consist of two side pieces, a separate one-piece band, and a countersunk crown piece. The inner lining consists of two side pieces and the crown, albeit the left side of the lining has been pieced together with two pieces of scrap. The crown appears to be of pasteboard. The height of the cap in front is three inches.

The enameled rain cover fits over the cap and is made with two side pieces and a crown piece. It will be described fully in Part IV.

The next cap that appears to have been a product an Alabama depot was worn by Arthur A. Crews of the 29th Alabama Infantry. The cap’s provenance is a bit more tenuous than Chalaron’s. Crews accompanied the Army of Tennessee on its retreat from the Tennessee Campaign, where it came to rest in Northern Mississippi. Some weeks later, his regiment deployed to the Carolinas with the portion of the Army of Tennessee that was sent east. Crews ended the war at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865.[89] The cloth of Crews’ cap matches the linsey weave that is well documented to the Montgomery Depot clothing factories. In fact, it is perfect match with that of the “Thomas Taylor” jacket: a jacket made from linsey purchased from the Confederate quartermaster in Montgomery in November 1863.[90] As such, Crews’ cap was likely made in Montgomery and issued to him before he departed for the Carolinas.

The cap’s weave is one woolen weft yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over two woolen weft yarns. This woolen weft yarn is oatmeal, natural white colored; the cotton warp yarn is light, golden tan colored. The overall effect of the cloth color is a light, dusty tan. The nap is still intact in some patches, and appears to have been steel gray. The non-functional, one-piece chinstrap is intact, albeit faded. It is a woven tulle band, now black and brown, but probably originally black. The buttons are also intact: cloth covered, two-piece metal. The visor is made from a single piece of leather. Both the glazing and paint are worn away, leaving it a medium-dark brown color. The visor is unusual in that the front width is only one-and-a-half inches, whereas most Confederate visors are about two inches wide. Its shape is also quite distinct, being somewhat more curved along the outer front edge than the typical Confederate visor. The sweatband (now missing) was made from enameled cloth (evident by the paint stains left on the plain weave, cotton lining, where it once was). The lining material appears to be a lightweight, tabby weave, cotton muslin. The tailoring follows the quintessential chasseur pattern having a one-piece band, low sides and countersunk crown. The front height of the cap is three inches.[91]

The cap’s weave is one woolen weft yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp yarn under two and over two woolen weft yarns. This woolen weft yarn is oatmeal, natural white colored; the cotton warp yarn is light, golden tan colored. The overall effect of the cloth color is a light, dusty tan. The nap is still intact in some patches, and appears to have been steel gray. The non-functional, one-piece chinstrap is intact, albeit faded. It is a woven tulle band, now black and brown, but probably originally black. The buttons are also intact: cloth covered, two-piece metal. The visor is made from a single piece of leather. Both the glazing and paint are worn away, leaving it a medium-dark brown color. The visor is unusual in that the front width is only one-and-a-half inches, whereas most Confederate visors are about two inches wide. Its shape is also quite distinct, being somewhat more curved along the outer front edge than the typical Confederate visor. The sweatband (now missing) was made from enameled cloth (evident by the paint stains left on the plain weave, cotton lining, where it once was). The lining material appears to be a lightweight, tabby weave, cotton muslin. The tailoring follows the quintessential chasseur pattern having a one-piece band, low sides and countersunk crown. The front height of the cap is three inches.[91]

072l: The interior view of the cap shows the underside of the visor and the lightweight, cotton-fabric lining. The visor of the Crew's cap was attached in the flimsy manner observed in many of the Richmond Depot caps. There are only nine, widely-spaced places for stitches (one of the sets of stitch holes is missing along with the right-side end of the visor). Artifact courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

The last original cap affiliated with the Lower South was worn by Corporal Bluford Watson Adams of the 4th Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, CSA. Adams surrendered to Union forces at Macon, Georgia on 9 May 1865. Presumably, he received his cap from this region shortly beforehand.[92]

The Adams cap has a leather visor, which in form and appearance is similar to that observed in the Crews cap. In fact, both the Crews and Adams cap visors appear to have been made by the same manufacturer: shape and dimensions are nearly identical. The Adams visor is about a quarter wider across the front than the Crews, but the front edge to inside curve at the center cap seam is 1 ½ inches for both. As with the Crews visor, all traces of glazing are now absent from the Adams visor. The chinstrap is missing, but one of the chinstrap buttons is intact: a white bone, trouser button covered with the cap’s basic cloth. The enamel cloth sweatband is partially intact, but the lining and band stiffening are missing. The sweatband is whip stitched to the base of the cap with an unfinished edge. The visor is sewn to the front of the cap with a back stitch. The overall front height of the cap is 3 ¾ inches, which is considerably taller than the typical chasseur style cap.

The cap’s basic cloth has a weave with one woolen weft yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and cotton warp yarn under two and over two woolen weft yarns. The overall color of the basic cloth is a natural, sheep’s gray. The woolen weft is sheep’s gray, and the fine cotton warp is white. The surface retains most of its light gray, very thick, raised nap. This fabric of the cap matches the uniform cloth of some Montgomery Depot uniforms, which strengthens its provenance to the vicinity of Alabama.[93]

The Adams cap has a leather visor, which in form and appearance is similar to that observed in the Crews cap. In fact, both the Crews and Adams cap visors appear to have been made by the same manufacturer: shape and dimensions are nearly identical. The Adams visor is about a quarter wider across the front than the Crews, but the front edge to inside curve at the center cap seam is 1 ½ inches for both. As with the Crews visor, all traces of glazing are now absent from the Adams visor. The chinstrap is missing, but one of the chinstrap buttons is intact: a white bone, trouser button covered with the cap’s basic cloth. The enamel cloth sweatband is partially intact, but the lining and band stiffening are missing. The sweatband is whip stitched to the base of the cap with an unfinished edge. The visor is sewn to the front of the cap with a back stitch. The overall front height of the cap is 3 ¾ inches, which is considerably taller than the typical chasseur style cap.

The cap’s basic cloth has a weave with one woolen weft yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and cotton warp yarn under two and over two woolen weft yarns. The overall color of the basic cloth is a natural, sheep’s gray. The woolen weft is sheep’s gray, and the fine cotton warp is white. The surface retains most of its light gray, very thick, raised nap. This fabric of the cap matches the uniform cloth of some Montgomery Depot uniforms, which strengthens its provenance to the vicinity of Alabama.[93]

073a: The front of the Bluford Watson Adams cap highlights the narrow visor that matches the one on the Crew's cap. While the Adams and Crews caps differ in their construction, and appear to have been made by different manufacturers, their visors came from the same supplyer. Artifact courtesy of the Bardstown Civil War Museum, Munson collection, Bardstown, Kentucky.

073l: This interior view of the cap shows the underside of the visor and the method of attachment. It is possible that the visor stitching is post war, conservator work. The enameled cloth sweatband is also visible, although the front part is missing. I was not allowed to removed the paper inside the cap and look at the interior lining and crown. The limited view, however, shows that the cap now has no band stiffening, and it may have been made without any. Artifact courtesy of the Bardstown Civil War Museum, Munson collection, Bardstown, Kentucky.

Several excellent images survive from the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. These date to photographic studios in either Mobile, Alabama or New Orleans, Louisiana just after the end of the war, in April or May of 1865. One such image depicts a full-length portrait of an unidentified Confederate soldier. He wears the Anderson Depot uniform, the jacket having a dark blue collar and brass buttons. The uniform includes a matching cap and pair of trousers. The cap has brass buttons, and may have a dark blue band.[94] The cap has brass buttons, and appears to have a dark blue band (assuming it is not a shadow). The visor shape conforms to that of the Crews cap. Based on the fact that the soldier has an Anderson Depot uniform, it’s plausible that his cap might come from the same place.