Basics about Confederate Uniforms

Fred Adolphus, May 10, 2014, (Updated 17 June 2024)

Over the years, I have collected data about the origins and characteristics of the Confederate uniform, and I finally decided to sum this information up in a concise article. While many seasoned Confederate buffs might find this very simplistic, I have been asked questions regarding these topics so often that I think this information will be useful for beginners as well as experienced uniformologists.

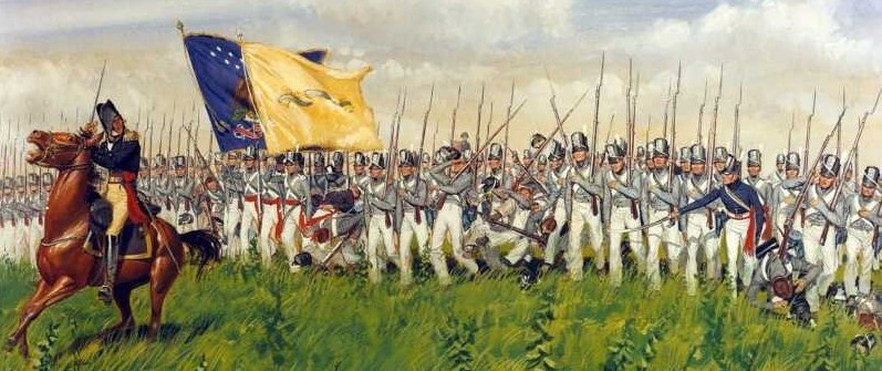

The Confederate uniform origins trace a diverse lineage. The basic color for the coat, gray, comes from the standard American state militia color cadet gray (which itself was derived from the earlier, medium gray fatigue uniform). Cadet gray came to embody the color of the "sovereign state" uniform color versus the dark blue of the "national government." This association was key to cadet gray's adoption by the South, given its connotations of state sovereignty. This light shade of bluish-gray was not any darker than the American army sky blue. But American cadet gray was not to become "Confederate" gray. It was too difficult to make in the South in large quantities, given limitations in resources, such as color fast dyes, mordants and manufacturing capacity. Instead, the standard British army, darker blue-gray became Confederate gray due to its availability through the blockade. The dark blue-gray kersey was still referred to as cadet gray (also frequently spelled “grey”). Contemporaries also called it Confederate gray, English army cloth, “gray cloth," kersey, or any combination of these terms to distinguish it from domestic weaves and other shades of gray. Therefore, the Confederate uniform quickly acquired British roots, in addition to its American antecedents.

Fred Adolphus, May 10, 2014, (Updated 17 June 2024)

Over the years, I have collected data about the origins and characteristics of the Confederate uniform, and I finally decided to sum this information up in a concise article. While many seasoned Confederate buffs might find this very simplistic, I have been asked questions regarding these topics so often that I think this information will be useful for beginners as well as experienced uniformologists.

The Confederate uniform origins trace a diverse lineage. The basic color for the coat, gray, comes from the standard American state militia color cadet gray (which itself was derived from the earlier, medium gray fatigue uniform). Cadet gray came to embody the color of the "sovereign state" uniform color versus the dark blue of the "national government." This association was key to cadet gray's adoption by the South, given its connotations of state sovereignty. This light shade of bluish-gray was not any darker than the American army sky blue. But American cadet gray was not to become "Confederate" gray. It was too difficult to make in the South in large quantities, given limitations in resources, such as color fast dyes, mordants and manufacturing capacity. Instead, the standard British army, darker blue-gray became Confederate gray due to its availability through the blockade. The dark blue-gray kersey was still referred to as cadet gray (also frequently spelled “grey”). Contemporaries also called it Confederate gray, English army cloth, “gray cloth," kersey, or any combination of these terms to distinguish it from domestic weaves and other shades of gray. Therefore, the Confederate uniform quickly acquired British roots, in addition to its American antecedents.

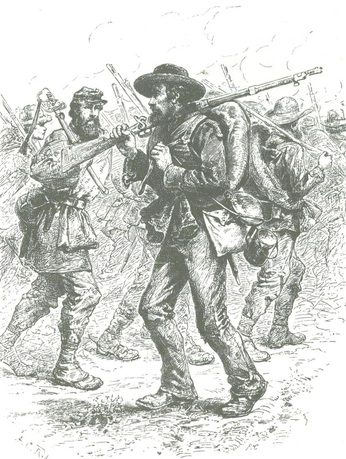

Image 1: The 6th U.S. Infantry Regiment at the Battle of Chippewa wore the gray fatigue jacket, normally used by state militias, instead of the blue tailcoats of the regular army. This caused the British to mistake them for militia, and underestimate their prowess at arms. The American army's use of gray uniforms began about this time. Image courtesy of the U.S. Army.

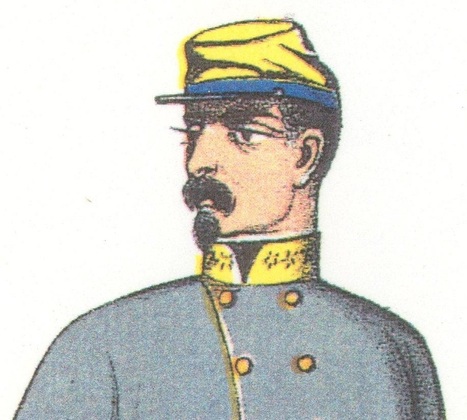

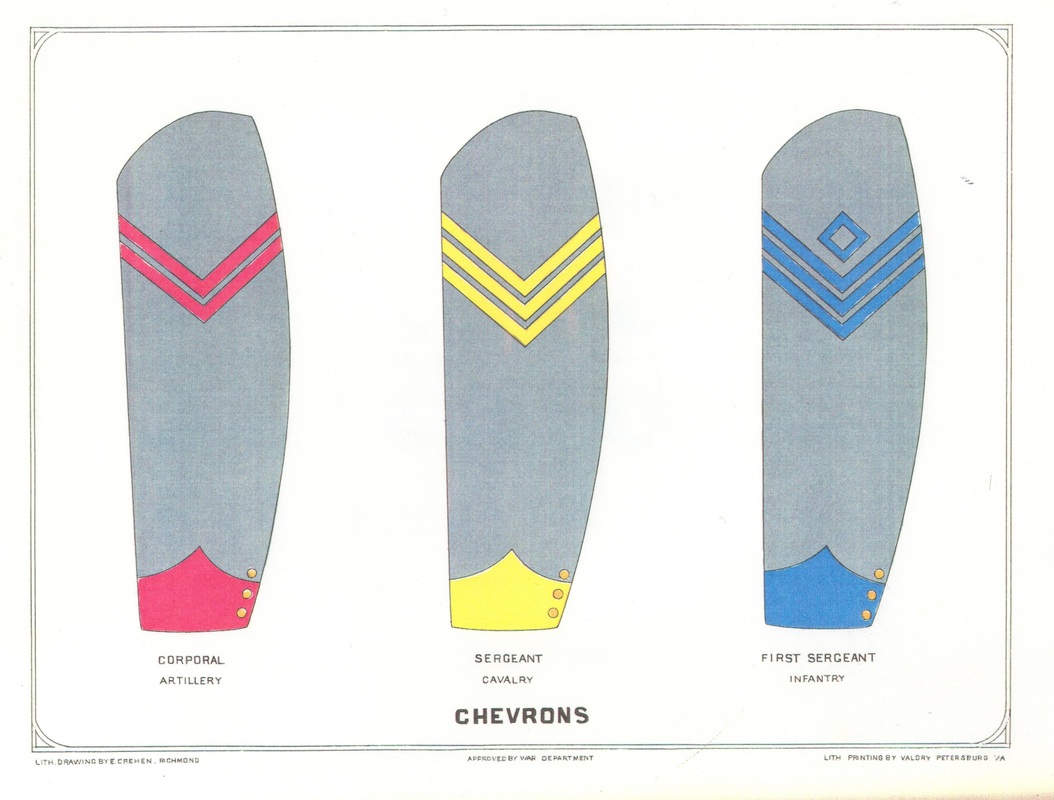

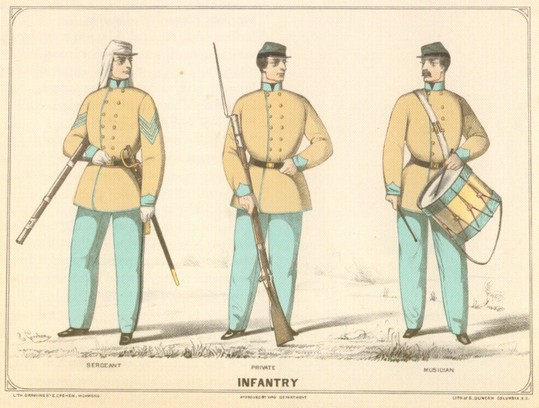

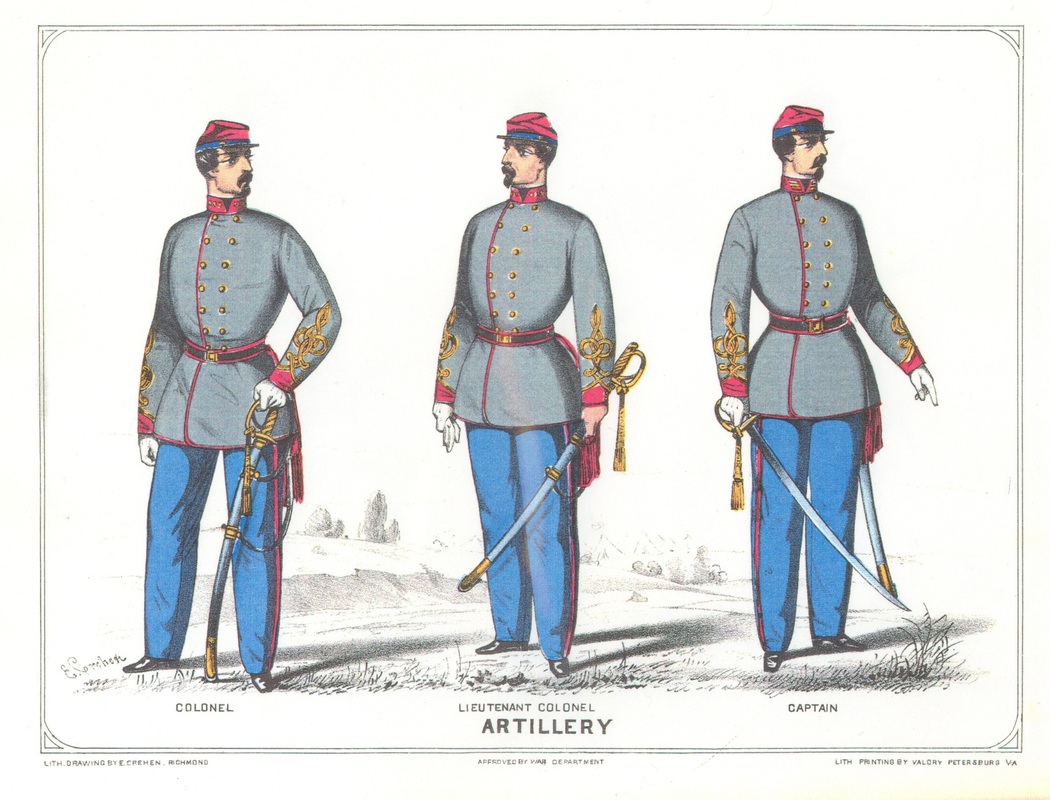

The uniform also had a French lineage. This is reflected in regulation cap, officially described as a kepi, but cut in the chasseur pattern with its hallmark countersunk crown, and low side pieces. Aside from the regulations, contemporaries seldom used the term "kepi," instead calling the regulation headgear a cap. The word "kepi," however, has gained currency since the war's end and become an iconic feature of the Confederate uniform. The official double-breasted frock coat was also similar to both the French army frock of the time, and to the Austrian army tunic. This feature can be attributed to the South’s respect for France as the preeminent military power of the day, as well as to the uniform's Prussian designer, Nicola Marschall, who incorporated Austrian characteristics into the Confederate tunic. In fact, Marschall copied both the design and color of the Austrian sharpshooter's tunic, it being gray with green-colored facings. British Lieutenant Colonel James Fremantle noted this during his travels through the Confederacy, remarking, "Most of the officers were dressed in uniform that is neat and serviceable - a bluish-gray frock coat of a color similar to Austrian yagers." The Confederate tunic was to have a relatively short skirt, similar to the French and Austrian tunics, but this stipulation was at odds with the prevailing fashion that dictated a knee-length skirt. As such, Confederate frocks almost always had long skirts, despite what was prescribed in the regulations. The officer's elaborate sleeve and cap braid also followed the French style, as did the that lack of shoulder straps. The officer collar rank closely matched the Austrian rank insignia, while the enlisted chevrons copied the American pattern.

Image 4: This painting of French soldiers during the Franco-Prussian War reflects the similarities between the French and Confederate uniforms. The kepi and double-breasted frocks, as well as the officer sleeve and cap braid were models for the Confederate uniform. Image in the public domain; Battle of Bapaume, General Faidherbe.

Image 10: The Confederate regulation frock coat was patterned after the Austrian army sharpshooter (Jaeger) uniform. This Germanic influence is not surprising, considering that Prussian artist and immigrant, Nicola Marschall designed the Confederate uniform. Image courtesy of the Kirk D. Lyons collection.

Two other American traits influenced the Confederate uniform: the branch-of-service colors, and the light blue pants. The Confederate regulations specified light blue as the pants color, probably intending the same "sky blue" shade as the Federal uniform had. This proved troublesome to make, however, given a lack of resources, so usually pants were made of the same color cloth as the tunic. Quartermasters did make limited quantities of light blue pants, however, when they had access to imported light blue cloth. The imported light blue cloth was different in color from the pre-war American sky blue cloth, just as the imported cadet gray was different from peacetime cadet gray. The Confederates imported a shade called "light French blue" that was darker and brighter than the Yankee sky blue. In any case, some Confederate commanders found the combination of Confederate blue-gray jackets and light blue pants too similar to the Yankee uniform, and thus confusing on the battlefield, and asked quartermasters to stop procuring the light French blue cloth.

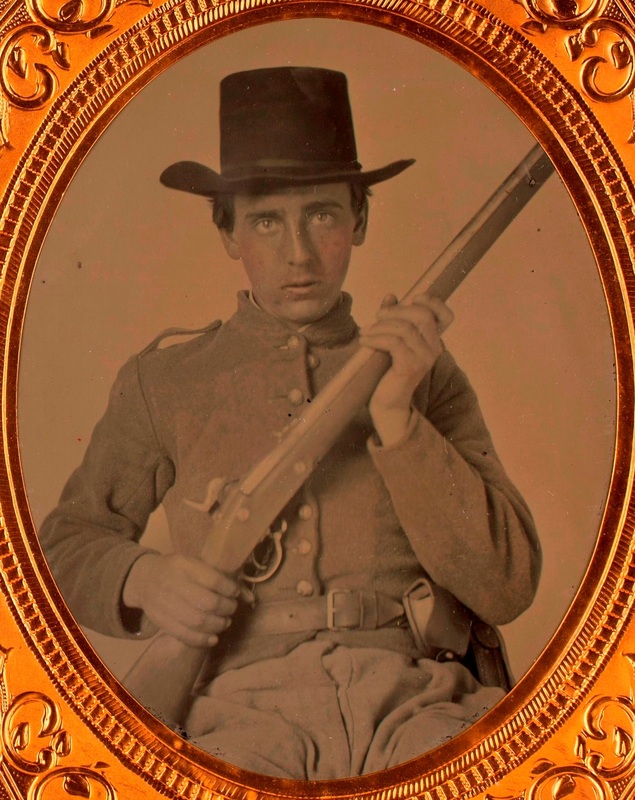

The elaborate regulation uniform, consisting of a cadet gray, double-breasted tunic; light blue pants; and, colorful kepis was problematic from the start. The South did not have the wide array of colored cloth to make such complex uniforms, nor were quartermasters inclined to squander resources making double-breasted tunics. In fact, the Confederate Quartermaster General published a revised set of uniforms regulations a month before the official Confederate uniform regulations appeared that prescribed a vastly simplified uniform. The double-breasted enlisted tunic (that called for fourteen large buttons and four small cuff buttons) was replaced by a single-breasted jacket that required but seven large buttons and less than two-thirds the amount of cloth. The cadet gray, light blue and various trim colors (red, yellow, light blue and dark blue) were also superceded by a single basic uniform color of gray. The clothing bureau settled on a loosely-defined jacket pattern that allowed for local improvisation based upon what materials a local quartermaster might have had available. In this regards, American practicality influenced the uniform that actually prevailed over the regulations: a short jacket and pants of a matching color in "gray…or any color [available]," and sparing of materials. The uniform was also topped off with the utilitarian, soft, wool felt slouch hat, another American influence that would symbolize the Confederate uniform both in fact and in lore.

The American-inspired branch-of-service colors of light blue for infantry, red for artillery and yellow for cavalry were far from universally employed. The colored trim cloth proved expensive, difficult to obtain, added to production time and costs, and impeded a universal issue to all branches. For these reasons, many depots opted for a plain, universal uniform, devoid of branch color. Nonetheless, some depots did add branch trim to their uniforms, and throughout the war, uniforms from diverse sources included branch colors. By far, red artillery trim predominated in its use. Light blue was used to a far lesser degree and yellow trim was rarely used on the Confederate uniform. This was due in no small part to the fact that red cloth or braid was easier to obtain than light blue or yellow trimmings. Dark blue trim generally supplanted light blue, since it, too, was easier to come by that light blue trim, and dark blue was frequently used on infantry uniforms early in the war, and later on depot jackets in the Lower South. Perhaps the most widespread trim color to be used, especially early in the war, was black. This color of cloth was easy to obtain since it was the prevailing men’s clothing color. As such, black not only became the default, substitute infantry trim color, it was frequently used by the cavalry, as well. Indeed, black became a sort of universal trim color used by all branches throughout the war.

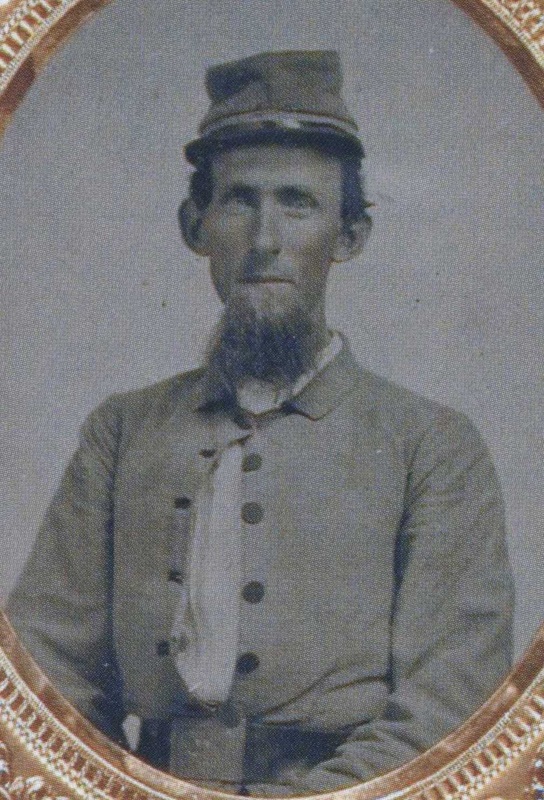

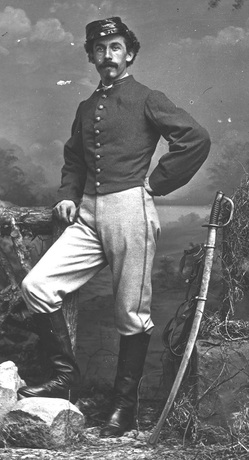

While the enlisted, double-breasted tunic was never universally adopted, the single-breasted, enlisted frock coat was the most widely worn "mustering-in" garment for the first year or so of the war. Few were made the quartermaster department, but companies going off to war had them them made locally by contractors, tailors or volunteer aid societies. While this garment is nowhere to be found in any Confederate regulation, it was, by 1861, America's unofficial militia uniform. It found its inspiration in the Pattern 1851, and 1859 US Army uniforms. Southerners especially copied the 1851 pattern frock coat with distinctive collar and cuff facings in the branch-of-service color. The cuff was fashioned with an upward point on the outside. This Confederate version of the pattern 1851 frock coat became universally copied from Texas to Virginia, using cadet gray, steel gray or butternut brown in lieu of dark blue for the basic cloth, and substituting the easily obtainable black for the usual branch color facings.

The American-inspired branch-of-service colors of light blue for infantry, red for artillery and yellow for cavalry were far from universally employed. The colored trim cloth proved expensive, difficult to obtain, added to production time and costs, and impeded a universal issue to all branches. For these reasons, many depots opted for a plain, universal uniform, devoid of branch color. Nonetheless, some depots did add branch trim to their uniforms, and throughout the war, uniforms from diverse sources included branch colors. By far, red artillery trim predominated in its use. Light blue was used to a far lesser degree and yellow trim was rarely used on the Confederate uniform. This was due in no small part to the fact that red cloth or braid was easier to obtain than light blue or yellow trimmings. Dark blue trim generally supplanted light blue, since it, too, was easier to come by that light blue trim, and dark blue was frequently used on infantry uniforms early in the war, and later on depot jackets in the Lower South. Perhaps the most widespread trim color to be used, especially early in the war, was black. This color of cloth was easy to obtain since it was the prevailing men’s clothing color. As such, black not only became the default, substitute infantry trim color, it was frequently used by the cavalry, as well. Indeed, black became a sort of universal trim color used by all branches throughout the war.

While the enlisted, double-breasted tunic was never universally adopted, the single-breasted, enlisted frock coat was the most widely worn "mustering-in" garment for the first year or so of the war. Few were made the quartermaster department, but companies going off to war had them them made locally by contractors, tailors or volunteer aid societies. While this garment is nowhere to be found in any Confederate regulation, it was, by 1861, America's unofficial militia uniform. It found its inspiration in the Pattern 1851, and 1859 US Army uniforms. Southerners especially copied the 1851 pattern frock coat with distinctive collar and cuff facings in the branch-of-service color. The cuff was fashioned with an upward point on the outside. This Confederate version of the pattern 1851 frock coat became universally copied from Texas to Virginia, using cadet gray, steel gray or butternut brown in lieu of dark blue for the basic cloth, and substituting the easily obtainable black for the usual branch color facings.

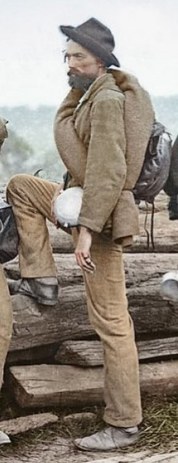

Image 25: Abraham Adler, Company E, 21st Mississippi Infantry, wore this Richmond jacket at the battle of Chickamauga. Although it has faded to tan from a gray color, its butternut shade would have been acceptable uniform color to Confederate quartermasters. Artifact courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana.

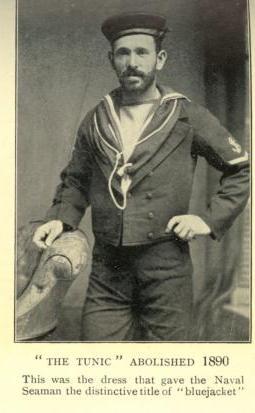

The Confederate jacket was often referred to as a “shell” jacket, a term with nautical roots. The shell jacket was the universal sailor's garb, and the name comes from the British term "shell back," which was a nickname for British sailors. The other term used for the Confederate jacket, "roundabout," referred to the fatigue jackets made in the early nineteenth century, cut all the way around the waist, instead of being made with tails as coatees were. Confederate jacket patterns conformed only in the broadest sense: they had standing collars and wide sleeves. Many of the surviving jackets are also of a distinct color, known today as butternut, which become a Confederate icon.

The butternut icon deserves some explanation. When people think of butternut today, they are apt to describe it as a light, yellowish-brown. The origins of the term butternut are more complex, because it originally encompassed a color, a type of homespun cloth, and a people. The term originated in North. As numerous Southerners moved to southern Illinois and southern Indiana in the mid-nineteenth century, the native Northerners called them “butternuts” for the butternut-dyed, rough homespun cloth they wore. Later, during the Civil War, the they called Confederate soldiers “butternuts” using the same criteria: Southerners wearing rough-textured cloth of the characteristic light brown color. The nickname applied regardless of whether the color had originally been brown from walnut hull dye, or had been dyed gray at the mill and faded to brown. Equally so, it would have been applicable to homemade citizens garb, or to factory made uniforms, as long as the fabric's texture resembled "homespun." Southern-made cassinets, jeans and satinets might all have resembled homespun to a Northerner.

When considering butternut as a color, which the term eventually morphed into by the end of the war, it was a light tan to a light brown color, depending on how the fabric had been dyed. The original butternut color was derived from Northern home dying using walnut hulls of the white walnut tree, commonly known also as the butternut tree. The white walnut, or butternut tree’s botanical name is Juglans cinerea, and its range includes eastern North America from Canada, southwards to northern Alabama, and westwards to Minnesota and northern Arkansas. It is absent from most of the Southland. Northerners used butternut bark and nut rinds (hulls) to dye cloth to colors between light yellow and dark brown. The more concentrated the dye, the darker the resulting color. None used butternut dye used commercially; they used it exclusively for homespun cloth (hence its association with homespun). This white walnut, butternut dye rendered fabrics a light to medium, yellowish brown color.

Likewise, the eastern black walnut, Juglans nigra, was more prevalent in the South. It is native to eastern North America, ranging from southern Ontario, westwards to southeast South Dakota, southwards to northern Florida and westwards from the east coast to central Texas. Southerners commonly used the black walnut tree, or “butternut” by extension, to dye their homespun clothing at the time of the Civil War. The black walnut drupes (hulls) contain juglone, and produce brownish-black dye. The tannins present in walnut hulls act as a mordant, aiding in the dyeing process, and making the resulting color extremely resistant to fading. Despite the black walnut dye’s potential to yield a dark, brownish-black color, rural folk generally obtained from it a light to medium, warm brown color for their homespun fabrics. Homemade, citizen clothes that were sent to Confederate soldiers from their families have this distinctive colorfast, warm, light brown shade.

When considering butternut as a color, which the term eventually morphed into by the end of the war, it was a light tan to a light brown color, depending on how the fabric had been dyed. The original butternut color was derived from Northern home dying using walnut hulls of the white walnut tree, commonly known also as the butternut tree. The white walnut, or butternut tree’s botanical name is Juglans cinerea, and its range includes eastern North America from Canada, southwards to northern Alabama, and westwards to Minnesota and northern Arkansas. It is absent from most of the Southland. Northerners used butternut bark and nut rinds (hulls) to dye cloth to colors between light yellow and dark brown. The more concentrated the dye, the darker the resulting color. None used butternut dye used commercially; they used it exclusively for homespun cloth (hence its association with homespun). This white walnut, butternut dye rendered fabrics a light to medium, yellowish brown color.

Likewise, the eastern black walnut, Juglans nigra, was more prevalent in the South. It is native to eastern North America, ranging from southern Ontario, westwards to southeast South Dakota, southwards to northern Florida and westwards from the east coast to central Texas. Southerners commonly used the black walnut tree, or “butternut” by extension, to dye their homespun clothing at the time of the Civil War. The black walnut drupes (hulls) contain juglone, and produce brownish-black dye. The tannins present in walnut hulls act as a mordant, aiding in the dyeing process, and making the resulting color extremely resistant to fading. Despite the black walnut dye’s potential to yield a dark, brownish-black color, rural folk generally obtained from it a light to medium, warm brown color for their homespun fabrics. Homemade, citizen clothes that were sent to Confederate soldiers from their families have this distinctive colorfast, warm, light brown shade.

By contrast, factory dyed fabrics, which generally ended up as army-cut uniforms, had its own distinctive brown shade: a color ranging from oatmeal to light tan to grayish tan or dark tan. This was because the fabric's woolen yarn had been dyed with an unstable vegetable dye and mordant, and had faded after exposure to sunlight. Typically, factories used logwood and indigo as dyes, and copperas and blue vitriol as mordants. The targeted colors were either "steel" gray (the most common domestically produced shade, being a medium gray, midway between white and black), domestic "cadet" grey (produced much less than steel gray, being a light blue-gray), or light to medium brown (rarely produced). Most such dyed yarns, observed on surviving garments, have faded to a tan or oatmeal color. Some retain traces of the gray nap in protected surface areas, and those that were dyed with especially good mordants retain their steel gray or sometimes brownish gray color. Some even faded to a natural white shade. Chemist and dye specialist Ben Tart of North Carolina has estimated that it took no more than a month of exposure to outdoor sunlight to fade a domestically dyed steel or cadet gray garment to a tan color.

While discussing the basic colors of Confederate uniforms, one must not forget the last two of these: sheep's gray and natural white. These colors were sometimes referred to as "drab." Numerous surviving uniforms indicate widespread usage of these colors in all parts of the Confederacy. Sheep's gray was easy to manufacture because it required no dyestuffs, yet rendered the fabric a colorfast light gray. Natural white was easier to produce than colored cloth because its yarns required no dying. The wool still had to be cleaned, however, which added to the fabric's comfort by removing excess lanolin. It carried a stigma, however, since white woolens had traditionally been used for slave clothing, and Confederate troops often resented the cloth's association with slaves. As such, the final source of origin for the white Confederate uniforms might be attributed to the American slave culture, as well as the time-honored practice of American practicality trumping all other considerations.

While discussing the basic colors of Confederate uniforms, one must not forget the last two of these: sheep's gray and natural white. These colors were sometimes referred to as "drab." Numerous surviving uniforms indicate widespread usage of these colors in all parts of the Confederacy. Sheep's gray was easy to manufacture because it required no dyestuffs, yet rendered the fabric a colorfast light gray. Natural white was easier to produce than colored cloth because its yarns required no dying. The wool still had to be cleaned, however, which added to the fabric's comfort by removing excess lanolin. It carried a stigma, however, since white woolens had traditionally been used for slave clothing, and Confederate troops often resented the cloth's association with slaves. As such, the final source of origin for the white Confederate uniforms might be attributed to the American slave culture, as well as the time-honored practice of American practicality trumping all other considerations.

A final remark is appropriate regarding Confederate uniform colors: butternut preceded the use of cadet gray by far. Many have the misguided notion that the high quality, imported British kersey, in cadet “grey” (as the British spelled it), was an early war product, and that as the South was blockaded, its quartermasters were reduced to using inferior “homespun” jeans, dyed with butternut juice. This idea is incorrect. The fact is that domestic fabrics that had been dyed domestically predominated early in the war. As foreign contracts came into play, cadet gray and light blue kerseys increasingly replaced these domestic fabrics in many Confederate armies. As the Confederate industrial base developed towards the end of the war, domestic fabrics were making strong “come-back.” By early 1865, however, the average Confederate soldier in the Army of Northern Virginia, the Mobile Garrison or the Trans-Mississippi was more likely to have been clad in imported, cadet gray kersey than in domestic, butternut jeans.

Having touched upon the origins of the Confederate uniform and its basic colors, some explanation of quartermaster clothing production and issue is necessary.

The first uniforms were furnished by several sources: local volunteer groups, small private contracts, and Confederate and state quartermasters. Because few believed the war would last very long, and the authorities did not want to invest public funds in permanent clothing factories, a system of compensation was developed for soldiers and regimental commanders who furnished theirr own clothing or bought clothing for their command. This stop-gap measure was known as the "commutation system." It was officially abolished in August of 1861, but due to inadequate production on the part of the quartermaster department, commutation lingered until October 1862. Quartermasters relied heavily upon private contractors to manufacture clothing at considerable short-term expense that avoided a long-term investment. By the middle of 1862, the quartermaster department had developed its own factories to a considerable extent, and Southerners were no longer averse to sponsoring such expenditures. They had come to realize that the war would last for a long time, and that the government needed to assume full responsibility for clothing the troops, along with establishing regular, government manufacturing facilities and fully operational clothing bureaus. As the war dragged on, the government weaned itself off of domestic contracting, to a large degree, by building its own factories, and supplemented its own production with foreign bought finished goods. By the end of the war, the South had a well-functioning manufacturing base, a reliable supply of foreign imported materiel, and domestic contracts that made up for the shortfalls in production that the former sources could not fulfill.

Having touched upon the origins of the Confederate uniform and its basic colors, some explanation of quartermaster clothing production and issue is necessary.

The first uniforms were furnished by several sources: local volunteer groups, small private contracts, and Confederate and state quartermasters. Because few believed the war would last very long, and the authorities did not want to invest public funds in permanent clothing factories, a system of compensation was developed for soldiers and regimental commanders who furnished theirr own clothing or bought clothing for their command. This stop-gap measure was known as the "commutation system." It was officially abolished in August of 1861, but due to inadequate production on the part of the quartermaster department, commutation lingered until October 1862. Quartermasters relied heavily upon private contractors to manufacture clothing at considerable short-term expense that avoided a long-term investment. By the middle of 1862, the quartermaster department had developed its own factories to a considerable extent, and Southerners were no longer averse to sponsoring such expenditures. They had come to realize that the war would last for a long time, and that the government needed to assume full responsibility for clothing the troops, along with establishing regular, government manufacturing facilities and fully operational clothing bureaus. As the war dragged on, the government weaned itself off of domestic contracting, to a large degree, by building its own factories, and supplemented its own production with foreign bought finished goods. By the end of the war, the South had a well-functioning manufacturing base, a reliable supply of foreign imported materiel, and domestic contracts that made up for the shortfalls in production that the former sources could not fulfill.

Image 35 (showing front and rear): Charles Herbst, Company I, 2nd Kentucky Infantry, wore a single-breasted, butternut frock coat typical of early war Confederate enlisted uniforms. The long skirts used too much fabric, however, which compelled quartermasters to adopt resource-conserving jackets. Artifact and image courtesy of the Mike Cunningham collection.

This was a gradual process, however, with overlap throughout the war in how the various methods of clothing procurement was accomplished. To start with, both the Confederate and the various state governments stepped in to mass produce clothing long before the Confederate government officially ended the commutation system in October 1862. In fact, by that time, numerous government "depots" had come into being and were in full production throughout the South, even though many used contractors as their source of supply instead of government-owned shops. To start with, the states took the initiative to manufacture clothing for their own troops serving in the Confederate army. Many of the states produced clothing from the very beginning to the end of the war. North Carolina is the best known among uniformologists, having produced vast quantities of uniforms and imported more besides. Less well known, however, were the clothing bureaus of Tennessee, Alabama, South Carolina and Georgia. Prior to its fall to the enemy, Tennessee supplied the needs of the Confederate army in the state. Alabama produced prodigious quantities of clothing for Alabama troops, and the other two aforementioned states provided modest quantities of clothing to their own soldiers. The State of Arkansas established a very successful clothing bureau that provided for troops until the Confederate authorities were able to take responsibility for quartermaster functions. Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi established modest clothing operations for their troops, as well. The important fact to keep in mind is that most of these state operations had been in operation from the beginning of the war, and all were functioning long before the Confederate quartermaster clothing bureaus started functioning.

Image 38: Amzi Leroy Williamson, Company B, 53rd North Carolina Infantry, wore this North Carolina jacket and cap. The State of North Carolina dyed its uniform fabrics either steel gray or cadet gray. In all likelihood, the present butternut color is a result of fading. Artifact and image courtesy of the Bill Ivey collection.

The Confederate clothing bureaus began somewhat haphazardly. They began as need arose and there was no one there to meet it. The Army of Mississippi managed organize a system of supply for its troops by the Battle of Shiloh. The San Antonio and Houston quartermasters opened government shops early in 1862, and had fully functioning operations by the time commutation officially ended. Judging from the plethora of images of Army of Northern Virginia troops wearing Richmond Depot jackets and caps early in the war, it would appear that the Confederate quartermaster in Richmond also had a well-functioning clothing bureau long before October 1862. Other Confederate quartermasters operated similar manufactories.

The first government depots were relatively small or dispersed. Those of Mississippi reflect this well. During the early part of the war, the Confederate clothing bureau there relied on the production of several small factories to furnish the soldier suits that it issued. Each individual contractor, or factory, produced a limited, but steady quantity of uniforms each week. The aggregate production of several small factories sufficed to meet the demand of the army in that area. For instance, on March 21, 1863, the Daily Southern Crisis newspaper in Jackson, Mississippi reported that five Mississippi factories, in Bankston, Columbus, Enterprise, Natchez and Woodville, together produced 5,000 garments weekly. Furthermore, each factory may have used its own patterns, which meant that there were subtle differences in the soldier suits produced at factory. This practice was fostered by the overall leniency in Confederate uniform specifications. As long as a manufacturer made jackets with standing collars, for instance, he was allowed considerable latitude for the rest of the pattern. The sleeves might be one- or two-piece; the jacket might have anywhere between five and nine buttons; it might have had an inside or an outside pockets; it might have had trim or been plain; it might have been made from cassinet, jeans or satinet; and, it might have been natural white, sheep's gray or steel gray. Considering the large number of small factories, the varying durations of their operations, and probability that each factory changed its patterns and materials ever so often, the variety of jackets emerging from the Confederate quartermaster bureau must have seemed endless.

Applying this aforementioned model described by the Daily Southern Crisis, the quartermaster in Jackson would receive five types of jackets, in varying proportions, that he issued out indiscriminately, i.e. with little regard to any typology as we uniformologists view it today. In 1863, a jacket was simply a jacket regardless, and when a brigade quartermaster received 2,000 suits of jackets and pants in Mississippi, they included whatever was in the depot store house on the day he picked up his clothing. The 2,000 suits might have been the products of five different factories, and all of the jackets may have varied slightly. The following array of "Deep South" factory jackets illustrates this diversity in construction and materials, yet all are plain shell jackets with standing collars.

Applying this aforementioned model described by the Daily Southern Crisis, the quartermaster in Jackson would receive five types of jackets, in varying proportions, that he issued out indiscriminately, i.e. with little regard to any typology as we uniformologists view it today. In 1863, a jacket was simply a jacket regardless, and when a brigade quartermaster received 2,000 suits of jackets and pants in Mississippi, they included whatever was in the depot store house on the day he picked up his clothing. The 2,000 suits might have been the products of five different factories, and all of the jackets may have varied slightly. The following array of "Deep South" factory jackets illustrates this diversity in construction and materials, yet all are plain shell jackets with standing collars.

45. John B.L. Grizzard, of Hanleiter’s Company, Georgia Light Artillery, wore this white jacket. It was probably made and issued in Georgia, given the factor of proximity, since Grizzard joined the army in February 1864 in Atlanta, and probably received clothing there soon afterwards. The basic cloth is a two-over-one, woolen-cotton jeans; natural white woolen weft; natural white cotton warp; unbleached osnaburg lining in the body; and, polished cotton inside the sleeves. It has a five-button front (brass dome buttons); six-piece body; two-piece sleeves; two-piece collar (inside and out); and, one outside left breast pocket. Artifact courtesy of the Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

46. An artillery jacket from an unidentified soldier also appears to be a Lower South product. Based on the fact that it has survived, and that it does not conform to later depot variants that introduced more stringent pattern guidelines, the jacket may have been made and issued in the Lower South in 1863 or 1864. It was presumably owned by a Mississippi soldier, based on its being part of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History collection. The basic cloth is a two-over-one jeans; sheep's gray woolen weft; natural white cotton warp; and, unbleached osnaburg lining. It has a six-button front (Federal, eagle C buttons); six-piece body; two-piece sleeves; two-piece collar (inside and out); two inside breast pockets; and, red woolen edging at the base of the cuffs, around the edge and base of the collar, and along the entire edge of the jacket. Artifact courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi.

47. Corporal J.C. Zehring's jacket typlifies the diversity of uniforms made in small factories until the very end of the war. Zehring, detailed from the 4th Tennessee Infantry, served as a hospital steward in Milledgeville, Georgia during the latter part of the war. His jacket may have been made and issued in Milledgeville in early 1865. The jacket cloth is brownish-tan, satinet or jeans; a woolen-cotton fabric, with a light brown woolen weft, and a natural white cotton warp; and, an unbleached osnaburg lining. It has a six-button front (Federal staff officer buttons); six-piece body; one-piece sleeves; and, two-piece collar. Artifact and image courtesy of Horse Soldier Military Antiques.

Confederate uniformologists have come to associate specific jacket characteristics with certain depots, but this ignores many actual circumstances. For instance, depots seldom concerned themselves with following stringent patterns: the broad criteria of furnishing short jackets with standing collars generally sufficed. These relaxed standards also fostered ease of production, as well, especially considering that shortages of materials often led to improvisation. Uniformologists should also bear in mind that Confederate jackets were not sacred garments, they were clothing: nothing more, and nothing less. Few would have thought much about the different number of buttons on their government-furnished jackets in 1863.

That said, Confederate quartermasters did achieve a fair degree of uniformity in their patterns as the war progressed, at least within their own depot-sphere. Some depots managed to produce well-defined patterns that remained constant from early in the war to the end. The jackets from the Richmond, Virginia and Columbus, Georgia Depots are the best examples. The nine-button Richmond jacket, with shoulder straps, belt loops and two piece sleeves, may have been made as early as 1861. The gray jeans Columbus jacket with one-piece sleeves and dark blue facings on the low cut collar and straight cuff facings was produced at least from the fall of 1862 until the end of the war. Other clearly definable jackets might not have been first produced until 1864. Such may have been the case with two depot jackets from the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. The first was probably made by the Columbus, Mississippi Depot. It was a five-button, satinet jacket, with two-piece sleeves, exterior breast pocket, and dark blue facing on the collar only. In order not to confuse it with the Columbus-Atlanta Depot uniform, I call it the Anderson jacket after Major Anderson who was in charge of that depot. The other had seven wooden buttons, a satinet body, one-piece sleeves, and exterior, left breast pockets, and often, a double row of top stitching around the edge. This second jacket was probably made by the Selma and Montgomery, Alabama operation, which I refer to as the Montgomery jacket. By the end of the war, it was indeed possible to observe clearly definable characteristics in the various depot jackets and assign them typologies (as Les Jensen did). Up until the last part of the war, however, this degree of uniformity did not necessarily exist within many depot operations. Even depots that had well-established uniform jacket patterns from early in the war still issued variants. The Richmond Depot issued limited quantities of four-button sack coats, and a five-button jacket variant from a factory in Southwest Virginia to supplement its production of the quintessential nine-button Richmond jacket. Even the Richmond jacket was sometimes made with six, seven or eight buttons instead of nine. Small Georgia factories produced a wide range of simple jackets throughout the war that supplemented the production of the well-defined Columbus jacket.

As a final comment on Confederate jackets, the number of buttons closing the front varied considerably. Confederate uniform and quartermaster regulations called for either seven-button jackets or double-breasted tunics with seven buttons per row. In practice, front button counts generally ranged from nine buttons to five. As a rule of thumb, frock coats and jackets made early in the war had eight- or nine-button fronts, mimicking the M1851 US Army frock coat. This extravagant expenditure of buttons tapered off after the first year of the war, and clothing manufacturers settled upon making jackets with five- or six-button fronts. The reduction in buttons eased manufacturing, sped fabrication and reduced costs. A close examination of early-war versus mid- to late-war jackets bears out this generalization. There were exceptions. For instance, the Richmond Clothing Bureau made its jacket for the entire war with a nine-button front, and two shoulder strap buttons until mid-1864. This amounted to a whopping eleven buttons per jacket. On the whole, however, Confederate depots had reduced the number of buttons closing their jackets from seven, eight or nine down to five or six.

That said, Confederate quartermasters did achieve a fair degree of uniformity in their patterns as the war progressed, at least within their own depot-sphere. Some depots managed to produce well-defined patterns that remained constant from early in the war to the end. The jackets from the Richmond, Virginia and Columbus, Georgia Depots are the best examples. The nine-button Richmond jacket, with shoulder straps, belt loops and two piece sleeves, may have been made as early as 1861. The gray jeans Columbus jacket with one-piece sleeves and dark blue facings on the low cut collar and straight cuff facings was produced at least from the fall of 1862 until the end of the war. Other clearly definable jackets might not have been first produced until 1864. Such may have been the case with two depot jackets from the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. The first was probably made by the Columbus, Mississippi Depot. It was a five-button, satinet jacket, with two-piece sleeves, exterior breast pocket, and dark blue facing on the collar only. In order not to confuse it with the Columbus-Atlanta Depot uniform, I call it the Anderson jacket after Major Anderson who was in charge of that depot. The other had seven wooden buttons, a satinet body, one-piece sleeves, and exterior, left breast pockets, and often, a double row of top stitching around the edge. This second jacket was probably made by the Selma and Montgomery, Alabama operation, which I refer to as the Montgomery jacket. By the end of the war, it was indeed possible to observe clearly definable characteristics in the various depot jackets and assign them typologies (as Les Jensen did). Up until the last part of the war, however, this degree of uniformity did not necessarily exist within many depot operations. Even depots that had well-established uniform jacket patterns from early in the war still issued variants. The Richmond Depot issued limited quantities of four-button sack coats, and a five-button jacket variant from a factory in Southwest Virginia to supplement its production of the quintessential nine-button Richmond jacket. Even the Richmond jacket was sometimes made with six, seven or eight buttons instead of nine. Small Georgia factories produced a wide range of simple jackets throughout the war that supplemented the production of the well-defined Columbus jacket.

As a final comment on Confederate jackets, the number of buttons closing the front varied considerably. Confederate uniform and quartermaster regulations called for either seven-button jackets or double-breasted tunics with seven buttons per row. In practice, front button counts generally ranged from nine buttons to five. As a rule of thumb, frock coats and jackets made early in the war had eight- or nine-button fronts, mimicking the M1851 US Army frock coat. This extravagant expenditure of buttons tapered off after the first year of the war, and clothing manufacturers settled upon making jackets with five- or six-button fronts. The reduction in buttons eased manufacturing, sped fabrication and reduced costs. A close examination of early-war versus mid- to late-war jackets bears out this generalization. There were exceptions. For instance, the Richmond Clothing Bureau made its jacket for the entire war with a nine-button front, and two shoulder strap buttons until mid-1864. This amounted to a whopping eleven buttons per jacket. On the whole, however, Confederate depots had reduced the number of buttons closing their jackets from seven, eight or nine down to five or six.

Image 52: Montgomery and Selma Depot had standardized another identifiable type of jacket by the latter part of the war with a considerable production. This "Montgomery" jacket is recognizable by its seven-button front (generally wooden quartermaster buttons), its sheep's gray or butternut-colored jeans fabric, its double-row of stitching along the outside edge, and an outside breast pocket. An unknown Confederate soldier wore this Montgomery jacket that's salient features include one-piece sleeves, and a six-piece body. Artifact courtesy of the Gettysburg National Military Park, Pennsylvania.

Image 53: The Augusta Depot produced an all woolen, plain-weave jacket, easily recognizable by its plumb collar on the left side and a six-button front (generally wooden quartermaster buttons). The plain weave consists of an undyed, natural white woolen warp and a dark, blue gray woolen weft, which gives the effect of a medium-dark, steel gray color from ten feet away. First Sergeant J. Fullerton Lyon, 19th South Carolina Infantry wore this Atlanta jacket. Its other salient features include one-piece sleeves, and a six-piece body. Artifact courtesy of the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina.

An English businessman traveling through the South, W.C. Corsan, described the Confederate soldiers that he saw from East Louisiana to South Carolina and Virginia. In his book Two Months in the Confederate States: An Englishman’s Travels through the South, Corsan remarked that Confederate dress and weaponry was similar throughout the regions that he visited from late October through early December 1862. He stated that all of the Confederate soldiers that he saw were clad, shod, and armed alike, ". . . with no attempt at uniform, either in hats, clothes, or anything else; but the same dingy homespun dress, nondescript caps, strong shoes, unshaven, unwashed, uncombed heads and faces, and the same bright rifles and bayonets I had seen through the South,” and “Their dress, arms, and accoutrements were the same as those of all the military I ever saw in the Confederacy, so that our description here [East Louisiana] will suffice for all… They wore suits (that is, a jacket and trousers) of “homespun” cotton, either grey or a dingy brown; a woollen shirt; rough strong shoes; and a sort of “billy-cock” hat, all of course much the worse for wear. They each had a splendid rifle and bayonet, in beautiful order; and cartridge-box, &c. of strong plain leather; but no sword, revolver, or bowie-knife. This, with a blanket rolled up and strapped to their shoulders, completed their equipment. Of course they were strangers, evidently, to razor, comb, brush, or even soap.” In Florence, South Carolina, November 1862, Corsan noted, “They were warmly clothed in homespun, woven thick, had mostly woollen shirts, good shoes, and over-coat or blankets, or both,” and in Petersburgh, Virginia, “. . . crowds of grey-vestured soldier with blankets, knapsacks, and rifles…” He described Southerners as his “butternut” friends, as well, in reference to the color of their clothing. Corsan left a splendid description of the typical Southern soldier for posterity.

Despite varying degrees of uniformity in jacket patterns, the overall popular image of the Confederate soldier remains very distinct: a lean soldier with either a slouch hat, with its brim pushed up in front, or a French style "kepi" cap; a gray or butternut shell jacket; a bedroll slung over his left shoulder and resting at his right hip; and, his socks pulled over the cuffs of his pants. In this guise, his statue still stands guard over many public squares throughout Dixie, watching over his beloved Southland forevermore.

Despite varying degrees of uniformity in jacket patterns, the overall popular image of the Confederate soldier remains very distinct: a lean soldier with either a slouch hat, with its brim pushed up in front, or a French style "kepi" cap; a gray or butternut shell jacket; a bedroll slung over his left shoulder and resting at his right hip; and, his socks pulled over the cuffs of his pants. In this guise, his statue still stands guard over many public squares throughout Dixie, watching over his beloved Southland forevermore.

The author extends his gratitude to all of the institutions and private individuals who made the images in this article available (as credited in the captions). Readers are reminded that the images herein are the property of Adolphus Confederate Uniforms, except where noted as being in the public domain, Library of Congress, or the U.S. Army. Even if an artifact or image is credited to a public institution, the image itself is the property of this website, having been made by, purchased by or given usage of to the author. Please do not reproduce these images without the obtaining the author's consent.