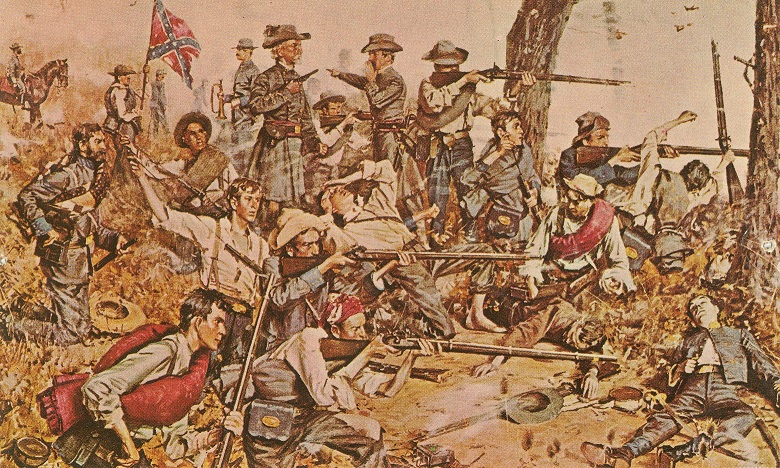

CONFEDERATE DEPOT UNIFORMS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ALABAMA, MISSISSIPPI AND EAST LOUISIANA, 1864-1865

Part I: The Jackets of Major William J. Anderson’s Depot, Columbus, Mississippi

By Frederick R. Adolphus, March 12, 2016; Updated November 22, 2021

As Les Jensen observed in his ground-breaking article, Survey of Government Made Confederate Jackets, there was a distinct style which he dubbed the “Department of Alabama” jacket. Jensen gave it this designation based on its provenance with the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. Jensen’s “Department of Alabama” jacket has a five-button front, an exterior pocket, a dark blue collar, and is made of tan-colored “woolen jean.” There is yet another equally prolific jacket type from the department, omitted from Jensen's study, made from grayish domestic twill with a seven-button front, and a double row of stitching around the edges.

The two distinct depot jackets warrant more study, and the first question involves where each type jacket was made. Each type was made at one of the two, late-war, clothing manufactories in the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, but assigning each type to one or the other operation is tenuous. A cursory overview of Confederate quartermaster operations in Alabama and Mississippi, however, provides a good basis for solving the mystery. By mid- to late 1864, there were two chief clothing manufacturing centers in the department: the Columbus, Mississippi operation, managed by Major William J. Anderson, and the factories in Selma and Montgomery under Captain William M. Gillaspie. Both of these operations furnished clothing to the department’s troops, most of whom were located in the Mobile area. The products of both manufacturing centers were moved by rail to Demopolis, Meridian or Mobile where they were issued to the army. Since the clothing from both operations was consolidated and distributed without regard for origin, it is difficult to determine which of the two types of jacket was made at which operation. Regrettably, neither quartermaster officer described his jackets. Both the Columbus and Montgomery operations produced roughly the same quantities of clothing, judging from surviving jackets and contemporary images, and both furnished clothing to Confederate troops around Mobile, and at large in the department, to include the portions of the Army of Tennessee that was reassigned to the Department in January 1865. In fact, roughly equal numbers of each type of jacket survive (eight of one and seven of the other), some with accompanying pants. The provenance for these uniforms, when available, is usually tied to the Mobile army. None of the jackets, except for one, have provenance that pre-dates December 1864. As such, both types might be presumed to be very late war jackets.

Before describing the jackets, a short explanation of the manufacturing centers and their goods is helpful. Starting with Alabama, three Alabama factories sold woolens to the Confederate quartermaster in 1864, according to an inspection report of Major G.W. Cunningham, the Atlanta Depot Quartermaster, the Tallassee, Scottsville and Tuscaloosa mills. The Tallassee mill provided the most woolens to the quartermaster, totaling 49,271 yards during the six-month period ending in May 1864. The Tuscaloosa mill had provided 11,580 yards and the Scottsville mill 8,826 yards during the same period. This amounted to 69,677 yards. Gillaspie reported on March 15, 1864, that the cloth used for his Selma Depot uniforms, “…for pants and jackets is principally obtained from the Tallassee factory, and is very substantial.” From these goods, the Selma Depot supplied the Mobile force with 2,000 uniforms per week by June 5, 1864. The Tallassee factory also furnished “cotton goods, drillings, etc,” according to a report of January 24, 1865.[1] The quartermaster at the Montgomery Depot in 1863 and early 1864, Captain A.P. Calhoun, would also have supplied the Mobile troops. Calhoun’s Montgomery production for 1863 amounted to over 22,000 outfits of pants, shirts, drawers, and caps. Both Selma and Montgomery had shoe factories, as well as clothing factories. Eventually, all of the clothing operations in Alabama were consolidated under Gillaspie’s charge and headquartered in Montgomery. The Alabama depots also used osnaburgs (a coarse, plain weave, unbleached cotton fabric), linseys, shirtings and drillings in making their uniforms. Osnaburgs were chief among these cotton fabrics, and were used primarily for linings. Factories that provided the Alabama depots with osnaburgs included the Dog River factory, Marion County Mills, the North Alabama mills, and the factories at Lawrenceburg, Tennessee.[2] Shirting and drilling were used to a lesser extent than osnaburgs for linings, but were nonetheless available in limited quantities. Several woolen fabrics were used as basic uniform cloth, including linsey, jeans, and satinet. Detailed soldier, Thomas Taylor, bought some linsey, shirting, and drilling fabrics from the Confederate quartermaster in Montgomery and used them to have a jacket and pair of pants made. The weave in Taylor’s linsey has a woolen weft yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and cotton warp yarn under two and over two woolen weft yarns. The cotton warp is a natural white color, and the woolen weft a sheep's gray, nearly steel gray color. The fabric has some very small patches of remnant nap, also sheep's gray in color, and the overall fabric color is a light steel gray. Taylor’s shirting, that lines the body, is a brown, striped cotton; and, the drilling, lining the sleeves, is an unbleached cotton twill.[3] The fabric weave matches that observed in the Arthur A. Crews cap, that also has an Alabama provenance. The State of Alabama quartermaster also mentions using satinet for making pants, and linseys, tweeds, jeans and kerseys for general uniform manufacture in 1861-62.[4] The weave associated with the Confederate uniforms of the Montgomery-Selma Depot is jeans.

Mississippi factories produced both osnaburgs for uniform linings and woolen-cotton basic uniform cloth. Major Livingston Mims, the Chief Confederate Quartermaster in Mississippi, reported on February 5, 1863 from Jackson that he had three depots for procurement: Major William J. Anderson’s in Columbus that furnished about 700 suits of clothing per week; Captain G.P. Theobald’s in Enterprise furnishing 400 pairs of shoes and 250 complete suits of clothing per month; and, Captain William H. Gillaspie’s in Jackson furnishing 1,000 suits of clothing per week and 40 blankets per day. Three factories, the Jackson, Woodville and Choctaw, made a sufficiency of woolen goods.[5] An article published shortly thereafter, on March 21, 1863, in Jackson’s Daily Southern Crisis newspaper, entitled “What Mississippi has Done,” recounted the state’s manufacturing achievements, and closely mirrored Mims’s February report. According to the article, the Jackson manufactory was making five thousand garments weekly, while factories at Bankston, Choctaw County, Columbus, Enterprise, Natchez and Woodville made up another five thousand per week; the hat factories at Jackson and Columbus made two hundred hats per day; a manufactory at Jackson turned out fifty blankets per day; and, private contractors supplied eight thousand pairs of shoes per week, while the quartermaster department was in the process of opening an “extensive Government shoe-shop” in Jackson with a capacity of turning out six thousand pairs of shoes per month.[6] In May 1863, Federal commanders substantiated this progress, noting in Jackson that both the state penitentiary and the Greene factory manufactured cotton goods, and likewise, there was a large cotton factory in Clinton.[7] Edward McGehee’s Woodville factory, when destroyed by the Federals in early 1863, was making dyed jeans for uniforms and osnaburg for feed sacks, all of which were sold to the quartermaster in Jackson.[8] James Wesson’s manufacturing complex at Bankston, Choctaw County, turned out significant quantities of cloth and shoes in the spring of 1863. Wesson’s mill was named the Mississippi Manufacturing Company, but was often referred to as the Bankston or Choctaw mill. Wesson furnished woolen jeans and linseys to the State of Mississippi and the CS quartermaster at Jackson and Demopolis from at least October1861 to May 1863. In September 1862, Wesson’s linseys were described as “W” and the jeans as either “W” or “Bro,” (presumably abbreviations for “white” and “brown.” Wesson furnished jackets and pants to the Confederate quartermaster at Jackson, Demopolis and Selma from at least January to August 1863 (the jackets going to Selma were described as “linsey.”). Wesson also furnished shoes to Jackson and Selma from at least March to September 1863.[9] Mims wrote on October 14, 1863, that he drew 4,000 yards of osnaburgs each week from local mills for fabricating into shirts and drawers.[10] Major William J. Anderson, who had been post quartermaster in Columbus, Mississippi since March 1862, and had been manufacturing clothing and shoes there since at least November 20, 1863, remarked on his use of jeans, linseys and osnaburgs for clothing; his use of both shoe pegs and shoe thread for making shoes; and, on successful contracts for 300 to 600 pairs of shoes per week, and 600 to 1,200 hats per month. The Mobile Register and Advertiser described Major Anderson’s accomplishments in an article dated May 17, 1864. Accordingly, Anderson’s Columbus Depot had furnished the army since January 1863 with 51,000 jackets, 50,000 pairs pants, 7,191 coats, 1,859 overcoats, 27,440 shirts, 15,278 pairs drawers, 20,415 hats and caps, 51,277 pairs boots and shoes, and 3,700 blankets. Wesson’s “Choctaw factory” supplied most of the material used to make the jackets, pants and coats: approximately 18,000 yards of jeans and linsey a month. Two companies in Columbus provided Anderson with shirting, and hats and caps. Sherman & Ramsay furnished 6,000 yards of shirting goods per month, and Hale & Sykes made hats and caps. Shoe manufactories in Lowndes, Oktibbeha and Choctaw Counties delivered between 2,500 to 3,000 pairs monthly, accounting for about two-thirds of Anderson’s shoe production.[11] In a letter of July 26, 1864, Anderson described his manufactures thusly, “The clothing material is excellent and the workmanship superior to any I have seen made elsewhere.” Taken as a whole, the manufacturing capacity in both Mississippi and Alabama had expanded by the latter part of the war, despite repeated raids by the Federals, and by 1864, both Anderson’s and Gillaspie’s depots were successful operations.

Unfortunately, no descriptions of the depots’ uniforms are available, so I have had to guess which depot made which of the two types. I have used the meager clues at hand to assign each jacket type to a depot. These include the proximity of one depot to a place of issue; and, the “linsey” weave found in one of the distinct types.

Using the proximity clue, the jacket belonging to Sergeant H.P. Kingsley was probably issued close to its point of origin. Kingsley, of the 2nd New York Cavalry, was a prisoner of war at Cahaba Prison near Selma. He had been captured in December 1864, and he received the jacket there: one of the seven-button jackets with the double row of topstitching. Based on this provenance, the seven-button jacket was likely manufactured at Montgomery. Furthermore, all of the seven-button jackets are made of the same type of basic cloth. This was apparently the “linsey” weave fabric that quartermasters used in Montgomery throughout the war to make enlisted uniforms. Based on these clues, I have dubbed the seven-button jacket the “Montgomery Depot” uniform. Given the previous assumption, the other jacket type with five-buttons, and a blue collar would have come from the Columbus, Mississippi Depot. I have dubbed it the “Anderson” uniform, after the depot's quartermaster, Major William J. Anderson. I have purposely avoided the term “Columbus” in order to avoid confusion with the well-coined term “Columbus jacket” that refers to the Columbus, Georgia Depot uniforms of Captain Francis W. Dillard. Therefore, the two types will be referred to henceforth as the Montgomery and Anderson jackets.

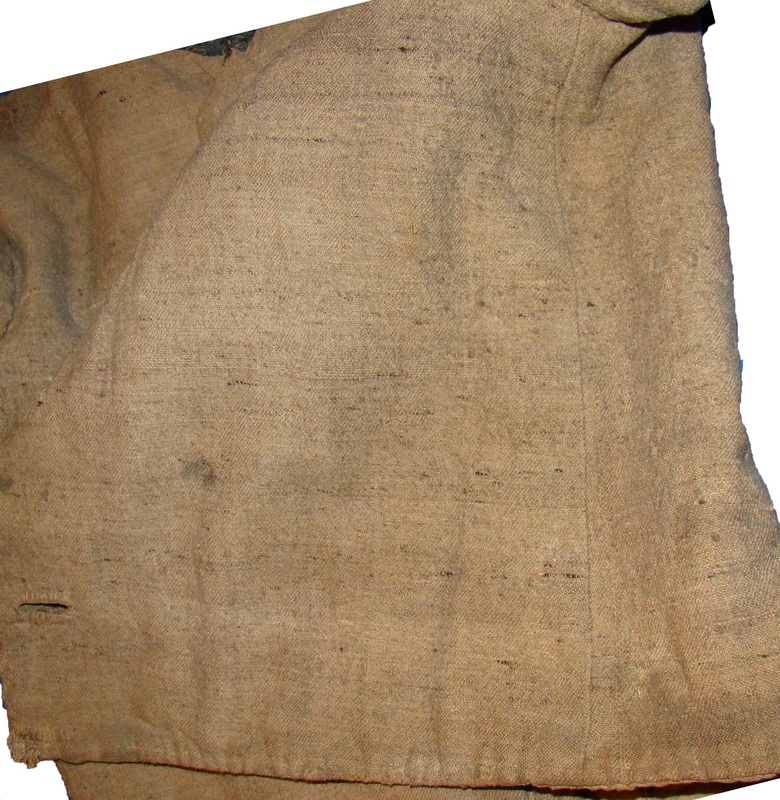

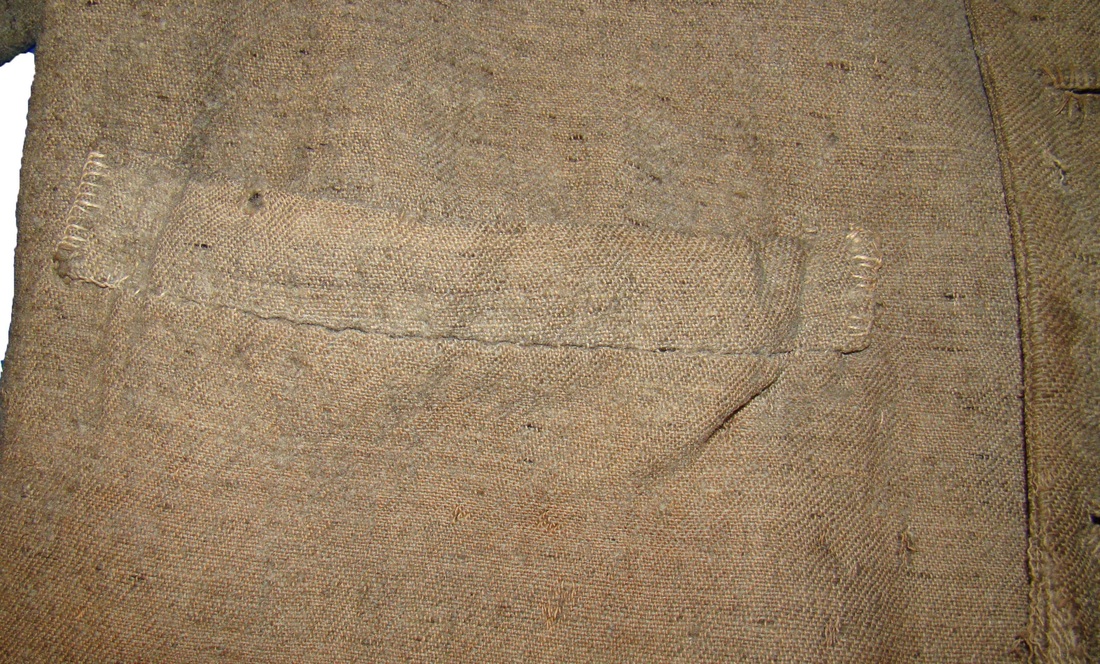

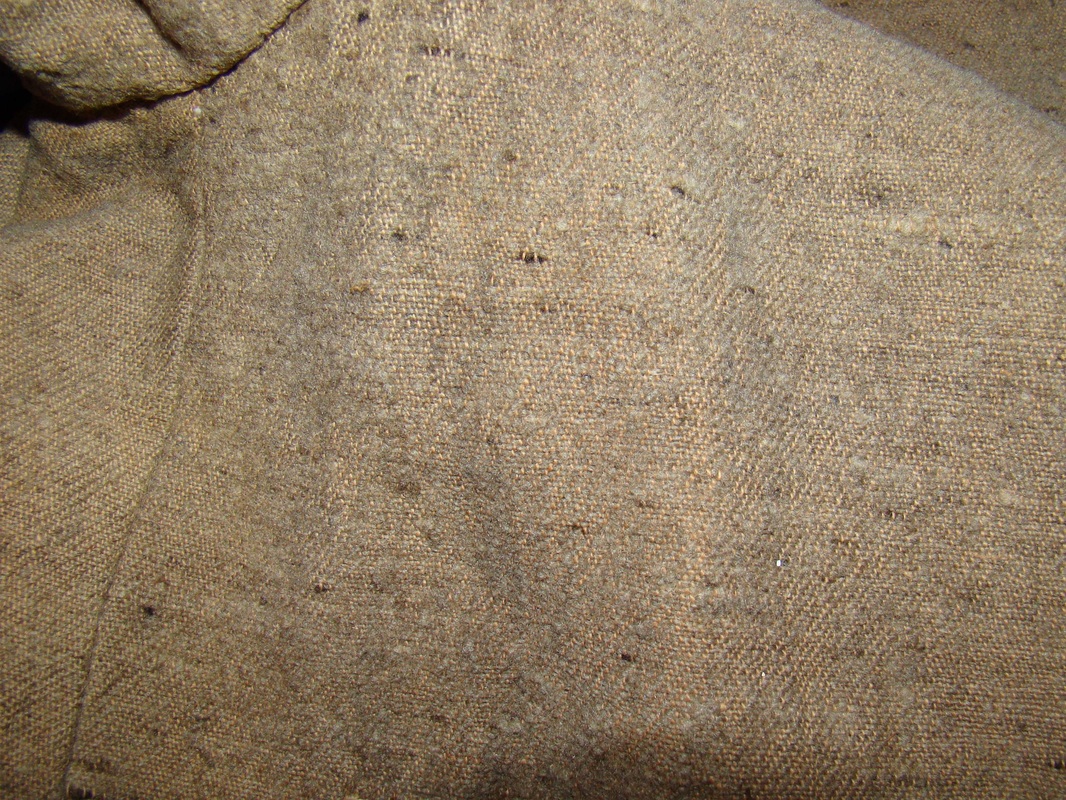

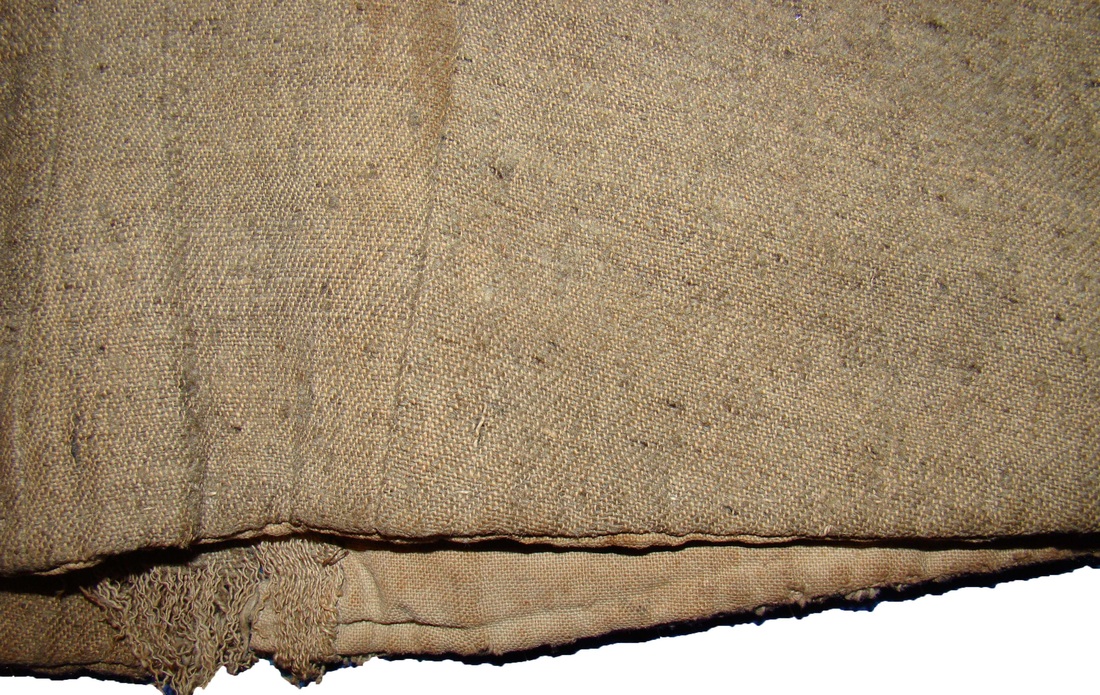

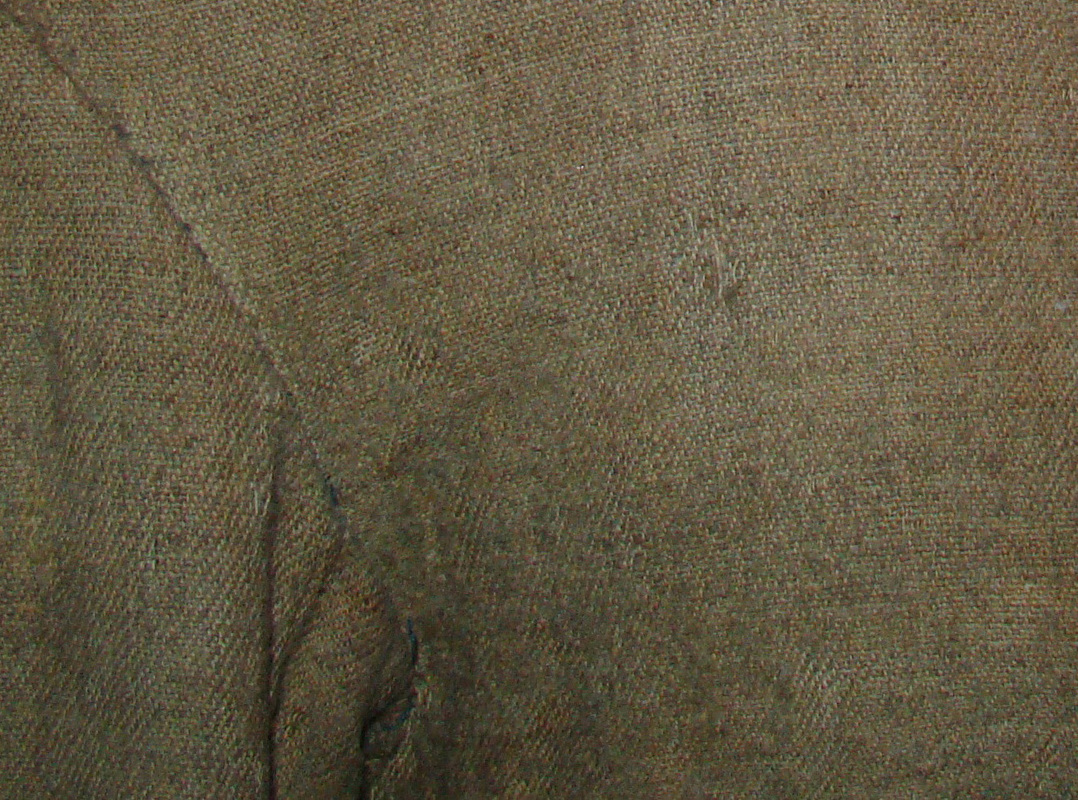

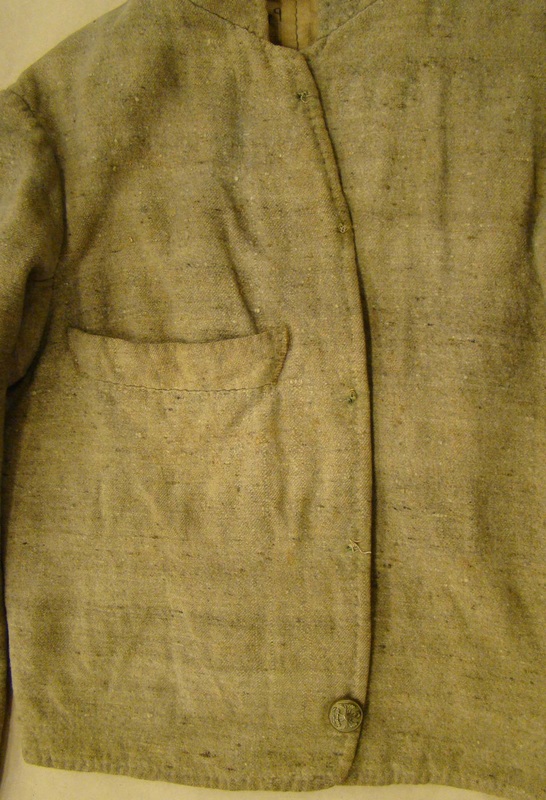

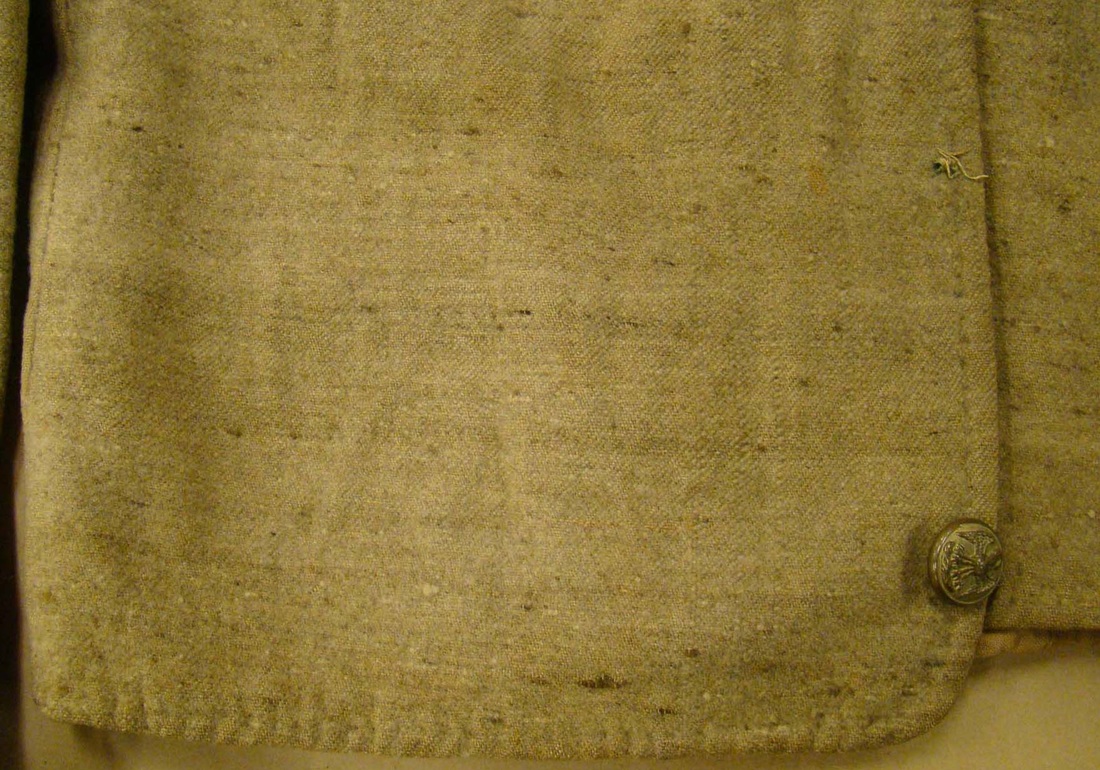

Starting with the Anderson-dubbed jacket, it has the following characteristics. Its fabric is a woolen-cotton, plain-weave,[12] now appearing a light tan or brownish-gray color. The cotton warp ranges in color from a natural white to a yellowish-white to a light tan. The woolen weft ranges in color from an oatmeal-gray to a grayish-tan. Many of the jackets have patches of the grayish nap intact. The woolen yarns may have originally been dyed a steel gray color, and have now faded to their light grayish tones, which suggests the jackets were originally steel gray. The blue collar trim weave typically has a woolen weft yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp under two and over two woolen weft yarns. The cotton warp is usually light tannish-brown color, and the woolen weft a bright, dark blue color. The lining is an unbleached cotton osnaburg. All of the jackets have identical tailoring consisting of a six-piece body, two-piece sleeves, one exterior inset pocket, one interior patch pocket (always on the opposite breast from the exterior pocket) which bottom edge varies in shape, five-button front, and, a two-piece collar (inside and out), generally with a dark blue, woolen-cotton jeans facing. Other similarities which vary slightly are wooden Confederate depot buttons and a single waist belt loop on the left side.[13] Two original jackets and several photos indicate that the wooden buttons may have been the typical, factory-applied button. At least three of the seven original jackets have belt loops on the left side, indicating that many of them were made with this feature. The exterior breast pocket was usually placed on the right side of the jacket. Of twelve jackets observed by the author (either originals or portraits) only two had the exterior pocket on the left side. Perhaps one of the most peculiar features is the manner of attaching the collar. After the jacket was finished, the collar was put on last. The inside and outside collar components were laid with their front sides flat against the lining and basic cloth, and their bottom seam edges aligned with edges of the neck hole. The inner and outer collar pieces were then joined with the neck hole seam lining and basic cloth between them, without any interlining. Once joined, each collar piece was folded upwards so that the back sides of the cloth faced together, the outer seam edges were folded inward along the edge and then whipstitched together to close the collar. In some instances, the exterior collar component was misaligned causing the lower edge to fall below the outside neck hole seamline, (such being unintentional). Other notable variations include cuff trim and the trim color. One surviving jacket has no colored trim (the collar being of the same fabric as the jacket); another has green collar and straight-cuff trim; and, a few, observed in photos and as an original, have red collars and pointed-cuff facings.

A feature common to both jacket types was the two-hole wooden, depot-applied button. This particular button came in a jacket size that was just over seven-eighths of an inch diameter, and in a pants size that was slightly more than five-eighths of an inch in diameter. The concept of using wooden buttons on Confederate depot clothing was not unique to the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. The Richmond, Virginia Depot manufactured similar buttons, except with four holes per button instead of two. The maker of the department’s depot buttons was William C. Allen of Prattville, Alabama. Prattville was about fifteen miles northwest of Montgomery. As early as October 1863, Captain Gillaspie was making monthly purchases of these buttons from Allen. In that month, he ordered, “… four hundred gross of good substantial wooden buttons per month, being 200 gross of pants and 200 Gross Jacket Buttons, to be equaled in style and workmanship to sample exhibited by said Allen, the holes to be well rounded and smooth so as to not cut the thread: the said Gillaspie to pay the said Allen the sum of Two Dollars per gross for said buttons, as they are delivered to him in Selma, Ala; and to furnish transportation for the same: The said Allen further promises to increase the number of said buttons as occasion may require.” This would have totaled 28,800 of each size. Gillaspie bought more of Allen’s buttons in 1864. In February he bought 745 gross (107,280) buttons; in March 375 gross (54,000) “Wood” buttons; and, in May 850 gross (122,400) “Wood” buttons. For purposes of this study, I have dubbed these the “Allen” buttons. Gillaspie’s records describe and document the buttons’ use at the Montgomery Depot. Even though Anderson left no similar records, he used the wooden Allen buttons at the Columbus, Mississippi Depot, as well. Incidentally, Captain George W. Cunningham, Quartermaster at the Atlanta, Georgia Depot, used this type of button, too.[14]

Of the surviving Anderson jackets, the most prevalent variant is first considered: the infantry jacket with a dark blue collar. This variant is represented by six jackets worn by the following soldiers: Thomas Jefferson Beck, Fenner’s Louisiana Light Artillery Battery; John Hoey, Company E, 22rd Louisiana Infantry; John A. Dolan, 14th (Austin’s) Battalion, Louisiana Sharp Shooters; Andrew Jackson Duncan, a Mississippi soldier; J.M. Donald, Company I, 6th Missouri Infantry; and Silas Buck, Comany D, 12th Mississippi Cavalry.

Thomas Jefferson Beck's infantry jacket has excellent provenance to Fenner’s Louisiana Artillery Battery. The command began its service as an infantry battalion, re-organized as light artillery, and served the last part of the war as heavy artillery at Mobile, Alabama. When Mobile fell, the battery armed itself as infantry and marched to Meridian, Mississippi, where the men were paroled on May 10, 1865.[15] The basic fabric has a yellowish-white cotton warp, and an oatmeal-gray woolen weft. Some of the gray nap is still present in patches. The collar facing has the usual weave; the bright, dark blue woolen weft; and, a light golden-brown cotton warp. The collar facing aligns with the neckhole seam. The jacket retains its original Allen buttons. The exterior pocket is set on the left breast with the welt's bottom edge just barely above middle button. The interior patch pocket, set in the right breast, has a “V” shaped bottom edge. The pocket opening employs the selvedge and is not folded over. The bottoms of the lapel fronts are barely rounded. The edges of the lapels have a single row of fairly tight, backstitched topstitching from the base of the collar to the point where the facing lapel meets the lining at the bottom edge of the jacket. The top edges of the collar and exterior left pocket welt are secured with a loose basting stitch. The bottom edge of the jacket and the cuffs have no topstitching. The jacket has a single belt loop on the left side.[16]

The two distinct depot jackets warrant more study, and the first question involves where each type jacket was made. Each type was made at one of the two, late-war, clothing manufactories in the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, but assigning each type to one or the other operation is tenuous. A cursory overview of Confederate quartermaster operations in Alabama and Mississippi, however, provides a good basis for solving the mystery. By mid- to late 1864, there were two chief clothing manufacturing centers in the department: the Columbus, Mississippi operation, managed by Major William J. Anderson, and the factories in Selma and Montgomery under Captain William M. Gillaspie. Both of these operations furnished clothing to the department’s troops, most of whom were located in the Mobile area. The products of both manufacturing centers were moved by rail to Demopolis, Meridian or Mobile where they were issued to the army. Since the clothing from both operations was consolidated and distributed without regard for origin, it is difficult to determine which of the two types of jacket was made at which operation. Regrettably, neither quartermaster officer described his jackets. Both the Columbus and Montgomery operations produced roughly the same quantities of clothing, judging from surviving jackets and contemporary images, and both furnished clothing to Confederate troops around Mobile, and at large in the department, to include the portions of the Army of Tennessee that was reassigned to the Department in January 1865. In fact, roughly equal numbers of each type of jacket survive (eight of one and seven of the other), some with accompanying pants. The provenance for these uniforms, when available, is usually tied to the Mobile army. None of the jackets, except for one, have provenance that pre-dates December 1864. As such, both types might be presumed to be very late war jackets.

Before describing the jackets, a short explanation of the manufacturing centers and their goods is helpful. Starting with Alabama, three Alabama factories sold woolens to the Confederate quartermaster in 1864, according to an inspection report of Major G.W. Cunningham, the Atlanta Depot Quartermaster, the Tallassee, Scottsville and Tuscaloosa mills. The Tallassee mill provided the most woolens to the quartermaster, totaling 49,271 yards during the six-month period ending in May 1864. The Tuscaloosa mill had provided 11,580 yards and the Scottsville mill 8,826 yards during the same period. This amounted to 69,677 yards. Gillaspie reported on March 15, 1864, that the cloth used for his Selma Depot uniforms, “…for pants and jackets is principally obtained from the Tallassee factory, and is very substantial.” From these goods, the Selma Depot supplied the Mobile force with 2,000 uniforms per week by June 5, 1864. The Tallassee factory also furnished “cotton goods, drillings, etc,” according to a report of January 24, 1865.[1] The quartermaster at the Montgomery Depot in 1863 and early 1864, Captain A.P. Calhoun, would also have supplied the Mobile troops. Calhoun’s Montgomery production for 1863 amounted to over 22,000 outfits of pants, shirts, drawers, and caps. Both Selma and Montgomery had shoe factories, as well as clothing factories. Eventually, all of the clothing operations in Alabama were consolidated under Gillaspie’s charge and headquartered in Montgomery. The Alabama depots also used osnaburgs (a coarse, plain weave, unbleached cotton fabric), linseys, shirtings and drillings in making their uniforms. Osnaburgs were chief among these cotton fabrics, and were used primarily for linings. Factories that provided the Alabama depots with osnaburgs included the Dog River factory, Marion County Mills, the North Alabama mills, and the factories at Lawrenceburg, Tennessee.[2] Shirting and drilling were used to a lesser extent than osnaburgs for linings, but were nonetheless available in limited quantities. Several woolen fabrics were used as basic uniform cloth, including linsey, jeans, and satinet. Detailed soldier, Thomas Taylor, bought some linsey, shirting, and drilling fabrics from the Confederate quartermaster in Montgomery and used them to have a jacket and pair of pants made. The weave in Taylor’s linsey has a woolen weft yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and cotton warp yarn under two and over two woolen weft yarns. The cotton warp is a natural white color, and the woolen weft a sheep's gray, nearly steel gray color. The fabric has some very small patches of remnant nap, also sheep's gray in color, and the overall fabric color is a light steel gray. Taylor’s shirting, that lines the body, is a brown, striped cotton; and, the drilling, lining the sleeves, is an unbleached cotton twill.[3] The fabric weave matches that observed in the Arthur A. Crews cap, that also has an Alabama provenance. The State of Alabama quartermaster also mentions using satinet for making pants, and linseys, tweeds, jeans and kerseys for general uniform manufacture in 1861-62.[4] The weave associated with the Confederate uniforms of the Montgomery-Selma Depot is jeans.

Mississippi factories produced both osnaburgs for uniform linings and woolen-cotton basic uniform cloth. Major Livingston Mims, the Chief Confederate Quartermaster in Mississippi, reported on February 5, 1863 from Jackson that he had three depots for procurement: Major William J. Anderson’s in Columbus that furnished about 700 suits of clothing per week; Captain G.P. Theobald’s in Enterprise furnishing 400 pairs of shoes and 250 complete suits of clothing per month; and, Captain William H. Gillaspie’s in Jackson furnishing 1,000 suits of clothing per week and 40 blankets per day. Three factories, the Jackson, Woodville and Choctaw, made a sufficiency of woolen goods.[5] An article published shortly thereafter, on March 21, 1863, in Jackson’s Daily Southern Crisis newspaper, entitled “What Mississippi has Done,” recounted the state’s manufacturing achievements, and closely mirrored Mims’s February report. According to the article, the Jackson manufactory was making five thousand garments weekly, while factories at Bankston, Choctaw County, Columbus, Enterprise, Natchez and Woodville made up another five thousand per week; the hat factories at Jackson and Columbus made two hundred hats per day; a manufactory at Jackson turned out fifty blankets per day; and, private contractors supplied eight thousand pairs of shoes per week, while the quartermaster department was in the process of opening an “extensive Government shoe-shop” in Jackson with a capacity of turning out six thousand pairs of shoes per month.[6] In May 1863, Federal commanders substantiated this progress, noting in Jackson that both the state penitentiary and the Greene factory manufactured cotton goods, and likewise, there was a large cotton factory in Clinton.[7] Edward McGehee’s Woodville factory, when destroyed by the Federals in early 1863, was making dyed jeans for uniforms and osnaburg for feed sacks, all of which were sold to the quartermaster in Jackson.[8] James Wesson’s manufacturing complex at Bankston, Choctaw County, turned out significant quantities of cloth and shoes in the spring of 1863. Wesson’s mill was named the Mississippi Manufacturing Company, but was often referred to as the Bankston or Choctaw mill. Wesson furnished woolen jeans and linseys to the State of Mississippi and the CS quartermaster at Jackson and Demopolis from at least October1861 to May 1863. In September 1862, Wesson’s linseys were described as “W” and the jeans as either “W” or “Bro,” (presumably abbreviations for “white” and “brown.” Wesson furnished jackets and pants to the Confederate quartermaster at Jackson, Demopolis and Selma from at least January to August 1863 (the jackets going to Selma were described as “linsey.”). Wesson also furnished shoes to Jackson and Selma from at least March to September 1863.[9] Mims wrote on October 14, 1863, that he drew 4,000 yards of osnaburgs each week from local mills for fabricating into shirts and drawers.[10] Major William J. Anderson, who had been post quartermaster in Columbus, Mississippi since March 1862, and had been manufacturing clothing and shoes there since at least November 20, 1863, remarked on his use of jeans, linseys and osnaburgs for clothing; his use of both shoe pegs and shoe thread for making shoes; and, on successful contracts for 300 to 600 pairs of shoes per week, and 600 to 1,200 hats per month. The Mobile Register and Advertiser described Major Anderson’s accomplishments in an article dated May 17, 1864. Accordingly, Anderson’s Columbus Depot had furnished the army since January 1863 with 51,000 jackets, 50,000 pairs pants, 7,191 coats, 1,859 overcoats, 27,440 shirts, 15,278 pairs drawers, 20,415 hats and caps, 51,277 pairs boots and shoes, and 3,700 blankets. Wesson’s “Choctaw factory” supplied most of the material used to make the jackets, pants and coats: approximately 18,000 yards of jeans and linsey a month. Two companies in Columbus provided Anderson with shirting, and hats and caps. Sherman & Ramsay furnished 6,000 yards of shirting goods per month, and Hale & Sykes made hats and caps. Shoe manufactories in Lowndes, Oktibbeha and Choctaw Counties delivered between 2,500 to 3,000 pairs monthly, accounting for about two-thirds of Anderson’s shoe production.[11] In a letter of July 26, 1864, Anderson described his manufactures thusly, “The clothing material is excellent and the workmanship superior to any I have seen made elsewhere.” Taken as a whole, the manufacturing capacity in both Mississippi and Alabama had expanded by the latter part of the war, despite repeated raids by the Federals, and by 1864, both Anderson’s and Gillaspie’s depots were successful operations.

Unfortunately, no descriptions of the depots’ uniforms are available, so I have had to guess which depot made which of the two types. I have used the meager clues at hand to assign each jacket type to a depot. These include the proximity of one depot to a place of issue; and, the “linsey” weave found in one of the distinct types.

Using the proximity clue, the jacket belonging to Sergeant H.P. Kingsley was probably issued close to its point of origin. Kingsley, of the 2nd New York Cavalry, was a prisoner of war at Cahaba Prison near Selma. He had been captured in December 1864, and he received the jacket there: one of the seven-button jackets with the double row of topstitching. Based on this provenance, the seven-button jacket was likely manufactured at Montgomery. Furthermore, all of the seven-button jackets are made of the same type of basic cloth. This was apparently the “linsey” weave fabric that quartermasters used in Montgomery throughout the war to make enlisted uniforms. Based on these clues, I have dubbed the seven-button jacket the “Montgomery Depot” uniform. Given the previous assumption, the other jacket type with five-buttons, and a blue collar would have come from the Columbus, Mississippi Depot. I have dubbed it the “Anderson” uniform, after the depot's quartermaster, Major William J. Anderson. I have purposely avoided the term “Columbus” in order to avoid confusion with the well-coined term “Columbus jacket” that refers to the Columbus, Georgia Depot uniforms of Captain Francis W. Dillard. Therefore, the two types will be referred to henceforth as the Montgomery and Anderson jackets.

Starting with the Anderson-dubbed jacket, it has the following characteristics. Its fabric is a woolen-cotton, plain-weave,[12] now appearing a light tan or brownish-gray color. The cotton warp ranges in color from a natural white to a yellowish-white to a light tan. The woolen weft ranges in color from an oatmeal-gray to a grayish-tan. Many of the jackets have patches of the grayish nap intact. The woolen yarns may have originally been dyed a steel gray color, and have now faded to their light grayish tones, which suggests the jackets were originally steel gray. The blue collar trim weave typically has a woolen weft yarn over two and under two cotton warp yarns, and one cotton warp under two and over two woolen weft yarns. The cotton warp is usually light tannish-brown color, and the woolen weft a bright, dark blue color. The lining is an unbleached cotton osnaburg. All of the jackets have identical tailoring consisting of a six-piece body, two-piece sleeves, one exterior inset pocket, one interior patch pocket (always on the opposite breast from the exterior pocket) which bottom edge varies in shape, five-button front, and, a two-piece collar (inside and out), generally with a dark blue, woolen-cotton jeans facing. Other similarities which vary slightly are wooden Confederate depot buttons and a single waist belt loop on the left side.[13] Two original jackets and several photos indicate that the wooden buttons may have been the typical, factory-applied button. At least three of the seven original jackets have belt loops on the left side, indicating that many of them were made with this feature. The exterior breast pocket was usually placed on the right side of the jacket. Of twelve jackets observed by the author (either originals or portraits) only two had the exterior pocket on the left side. Perhaps one of the most peculiar features is the manner of attaching the collar. After the jacket was finished, the collar was put on last. The inside and outside collar components were laid with their front sides flat against the lining and basic cloth, and their bottom seam edges aligned with edges of the neck hole. The inner and outer collar pieces were then joined with the neck hole seam lining and basic cloth between them, without any interlining. Once joined, each collar piece was folded upwards so that the back sides of the cloth faced together, the outer seam edges were folded inward along the edge and then whipstitched together to close the collar. In some instances, the exterior collar component was misaligned causing the lower edge to fall below the outside neck hole seamline, (such being unintentional). Other notable variations include cuff trim and the trim color. One surviving jacket has no colored trim (the collar being of the same fabric as the jacket); another has green collar and straight-cuff trim; and, a few, observed in photos and as an original, have red collars and pointed-cuff facings.

A feature common to both jacket types was the two-hole wooden, depot-applied button. This particular button came in a jacket size that was just over seven-eighths of an inch diameter, and in a pants size that was slightly more than five-eighths of an inch in diameter. The concept of using wooden buttons on Confederate depot clothing was not unique to the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. The Richmond, Virginia Depot manufactured similar buttons, except with four holes per button instead of two. The maker of the department’s depot buttons was William C. Allen of Prattville, Alabama. Prattville was about fifteen miles northwest of Montgomery. As early as October 1863, Captain Gillaspie was making monthly purchases of these buttons from Allen. In that month, he ordered, “… four hundred gross of good substantial wooden buttons per month, being 200 gross of pants and 200 Gross Jacket Buttons, to be equaled in style and workmanship to sample exhibited by said Allen, the holes to be well rounded and smooth so as to not cut the thread: the said Gillaspie to pay the said Allen the sum of Two Dollars per gross for said buttons, as they are delivered to him in Selma, Ala; and to furnish transportation for the same: The said Allen further promises to increase the number of said buttons as occasion may require.” This would have totaled 28,800 of each size. Gillaspie bought more of Allen’s buttons in 1864. In February he bought 745 gross (107,280) buttons; in March 375 gross (54,000) “Wood” buttons; and, in May 850 gross (122,400) “Wood” buttons. For purposes of this study, I have dubbed these the “Allen” buttons. Gillaspie’s records describe and document the buttons’ use at the Montgomery Depot. Even though Anderson left no similar records, he used the wooden Allen buttons at the Columbus, Mississippi Depot, as well. Incidentally, Captain George W. Cunningham, Quartermaster at the Atlanta, Georgia Depot, used this type of button, too.[14]

Of the surviving Anderson jackets, the most prevalent variant is first considered: the infantry jacket with a dark blue collar. This variant is represented by six jackets worn by the following soldiers: Thomas Jefferson Beck, Fenner’s Louisiana Light Artillery Battery; John Hoey, Company E, 22rd Louisiana Infantry; John A. Dolan, 14th (Austin’s) Battalion, Louisiana Sharp Shooters; Andrew Jackson Duncan, a Mississippi soldier; J.M. Donald, Company I, 6th Missouri Infantry; and Silas Buck, Comany D, 12th Mississippi Cavalry.

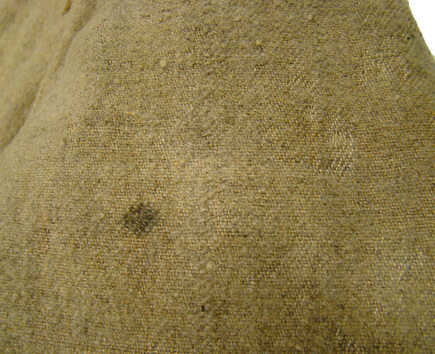

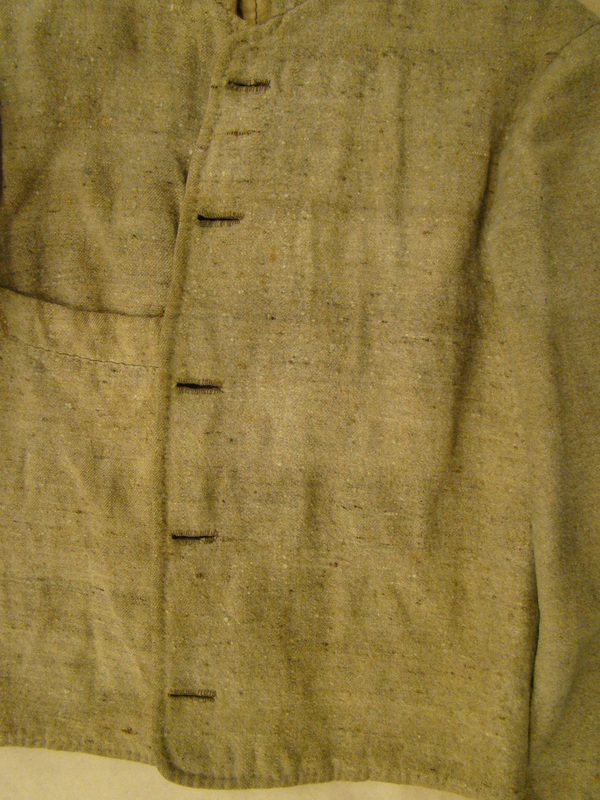

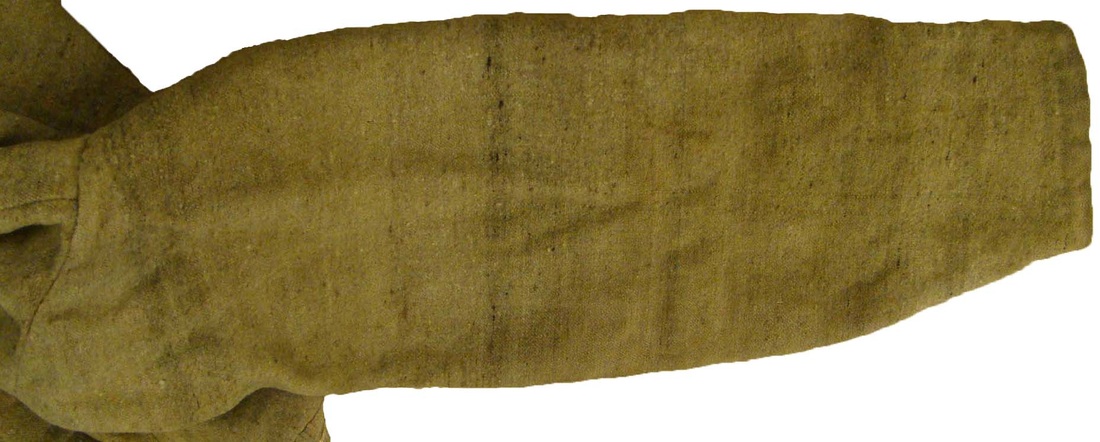

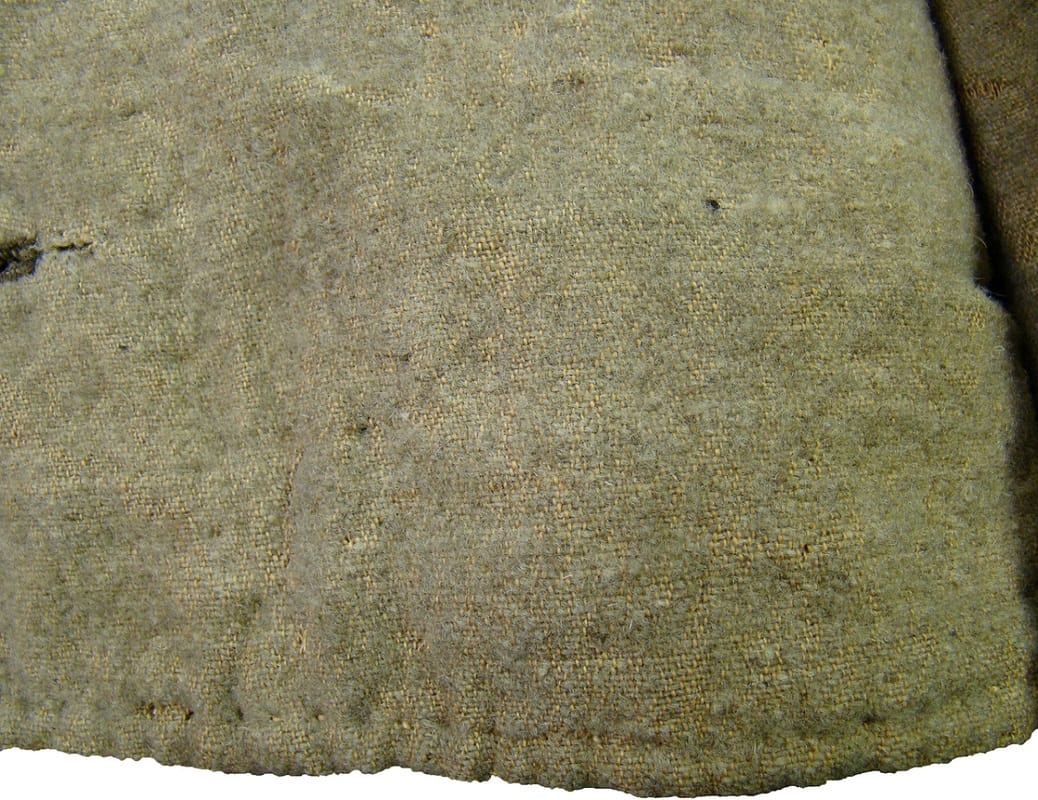

Thomas Jefferson Beck's infantry jacket has excellent provenance to Fenner’s Louisiana Artillery Battery. The command began its service as an infantry battalion, re-organized as light artillery, and served the last part of the war as heavy artillery at Mobile, Alabama. When Mobile fell, the battery armed itself as infantry and marched to Meridian, Mississippi, where the men were paroled on May 10, 1865.[15] The basic fabric has a yellowish-white cotton warp, and an oatmeal-gray woolen weft. Some of the gray nap is still present in patches. The collar facing has the usual weave; the bright, dark blue woolen weft; and, a light golden-brown cotton warp. The collar facing aligns with the neckhole seam. The jacket retains its original Allen buttons. The exterior pocket is set on the left breast with the welt's bottom edge just barely above middle button. The interior patch pocket, set in the right breast, has a “V” shaped bottom edge. The pocket opening employs the selvedge and is not folded over. The bottoms of the lapel fronts are barely rounded. The edges of the lapels have a single row of fairly tight, backstitched topstitching from the base of the collar to the point where the facing lapel meets the lining at the bottom edge of the jacket. The top edges of the collar and exterior left pocket welt are secured with a loose basting stitch. The bottom edge of the jacket and the cuffs have no topstitching. The jacket has a single belt loop on the left side.[16]

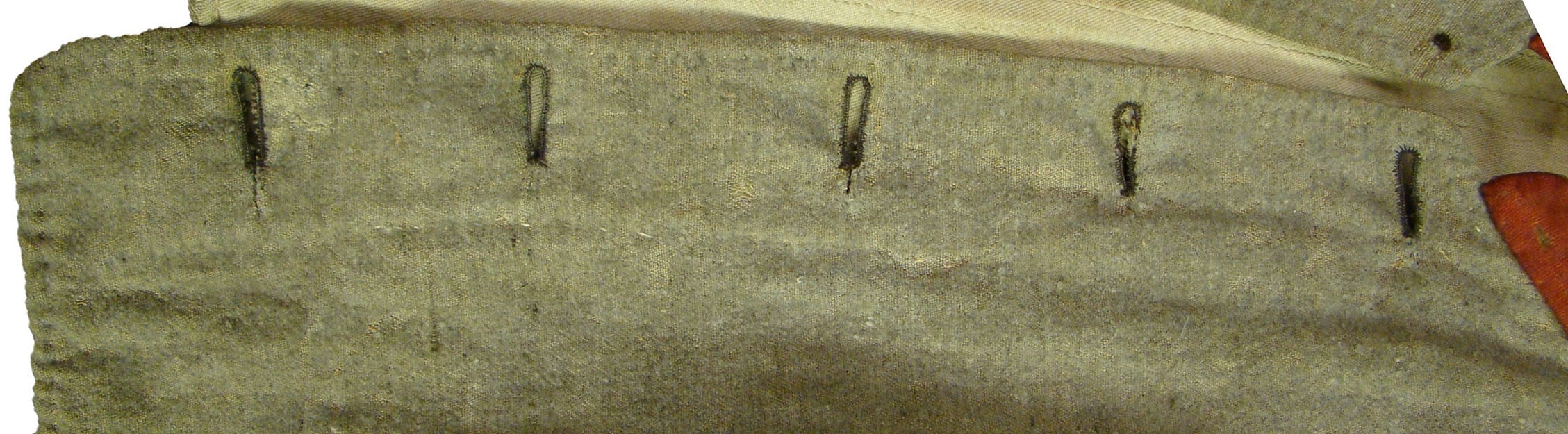

1a. A front view of Beck's jacket showing the wooden Allen buttons. The brindling in the cloth is especially visible in the left sleeve and at the level of the second button from the bottom. The Beck jacket artifact, in the 1-series of images, is courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

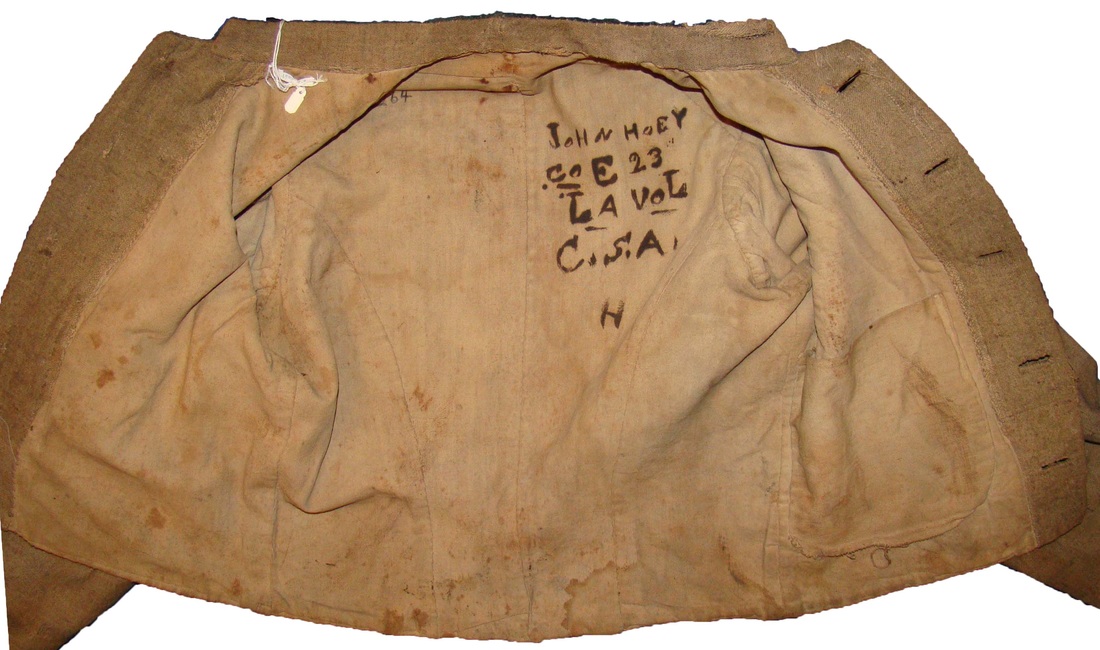

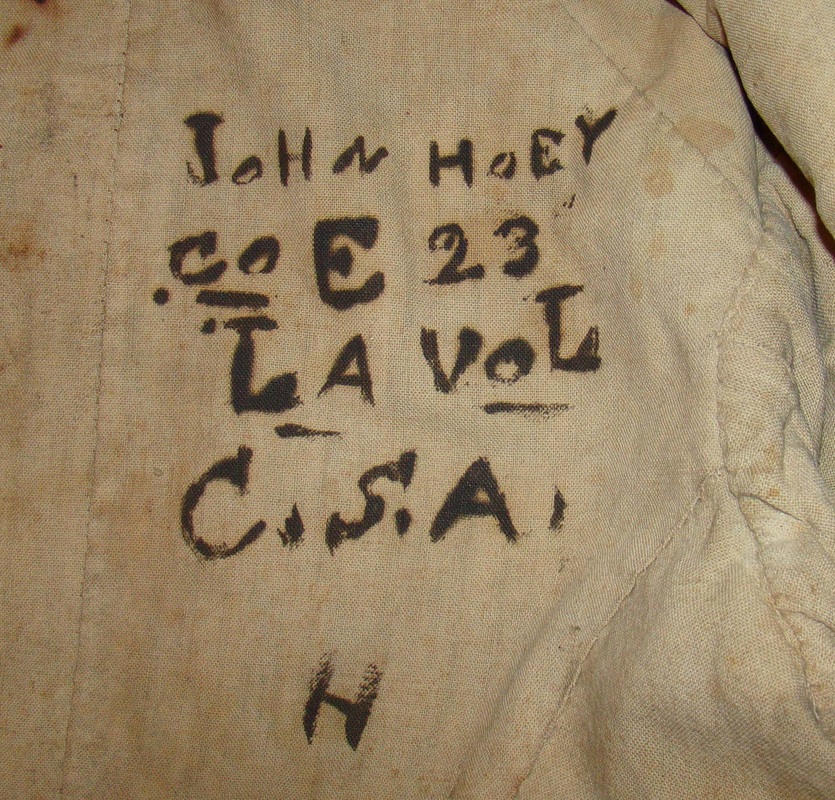

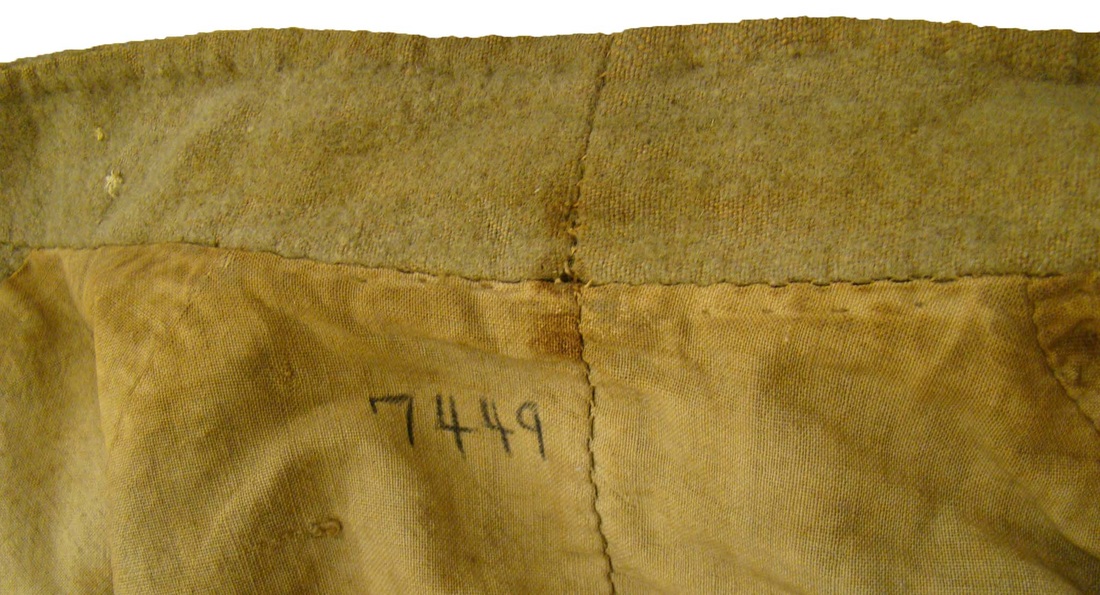

The next infantry jacket was owned by John Hoey (sometimes spelled Hoye, but pronounced by the family “Hoe-ey”), Company E, 22nd Louisiana Consolidated Infantry Regiment. Hoey had originally been part of the 23rd Louisiana Infantry until its incorporation into the 22nd Consolidated Regiment in January 1864. Hoey had enlisted in 1861, and his command had fought through the Vicksburg Campaign, after which it was paroled, exchanged and consolidated, and eventually assigned to army at Mobile. In 1865, Hoey fought at Spanish Fort, and after which his regiment moved to Meridian, Mississippi where it surrendered on May 8. He presumably received this jacket in the vicinity of Meridian or Mobile. As a tribute to his service, Hoey inscribed the lining of his jacket, similar to that of Dolan’s, with, “JOHN HOEY CO E 23 LA VOL C.S.A. H.”[17]

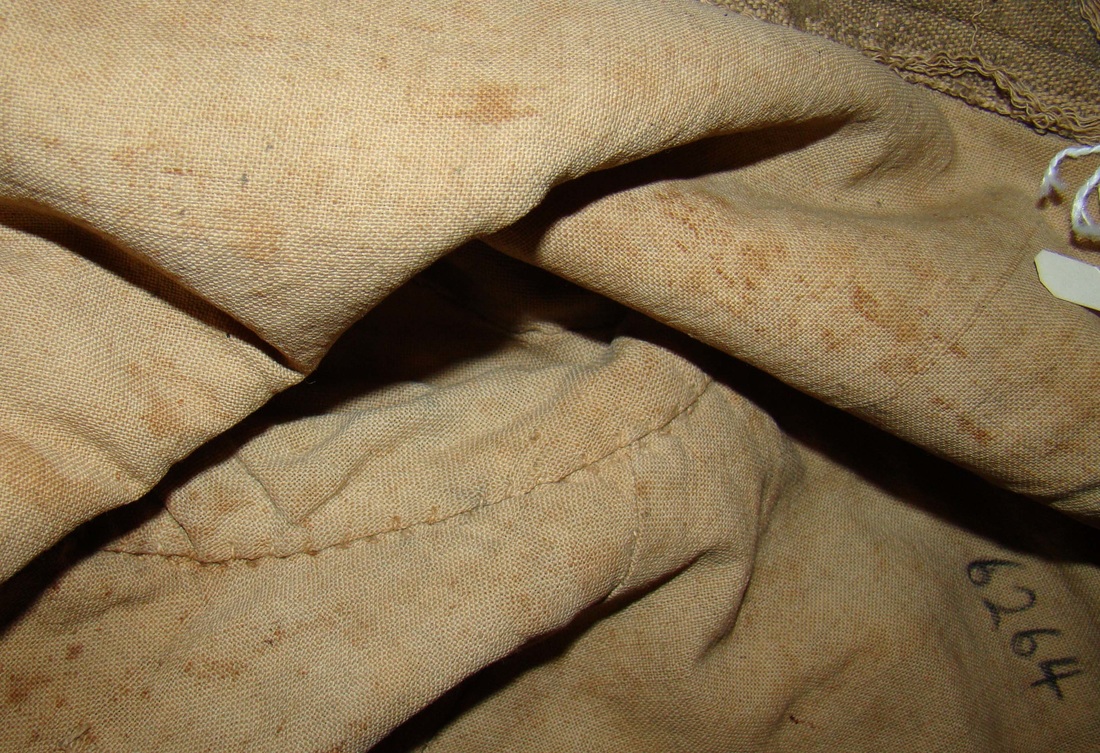

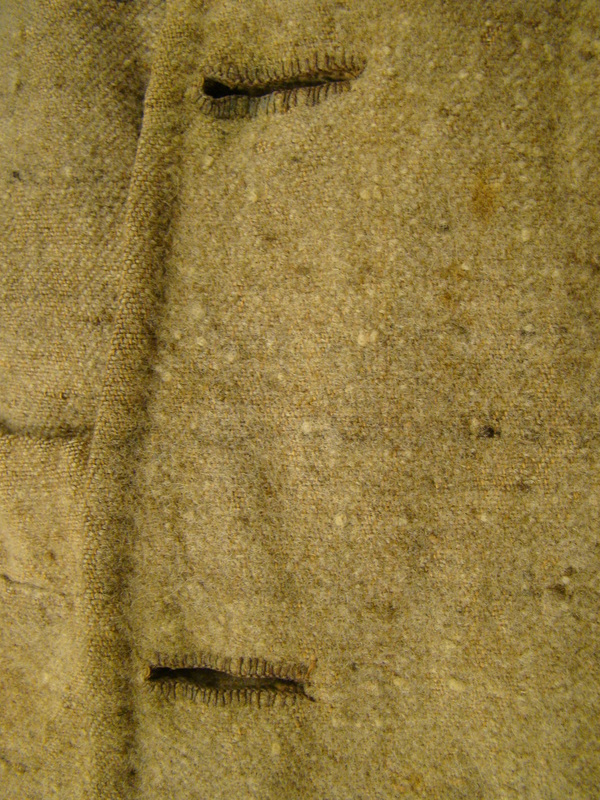

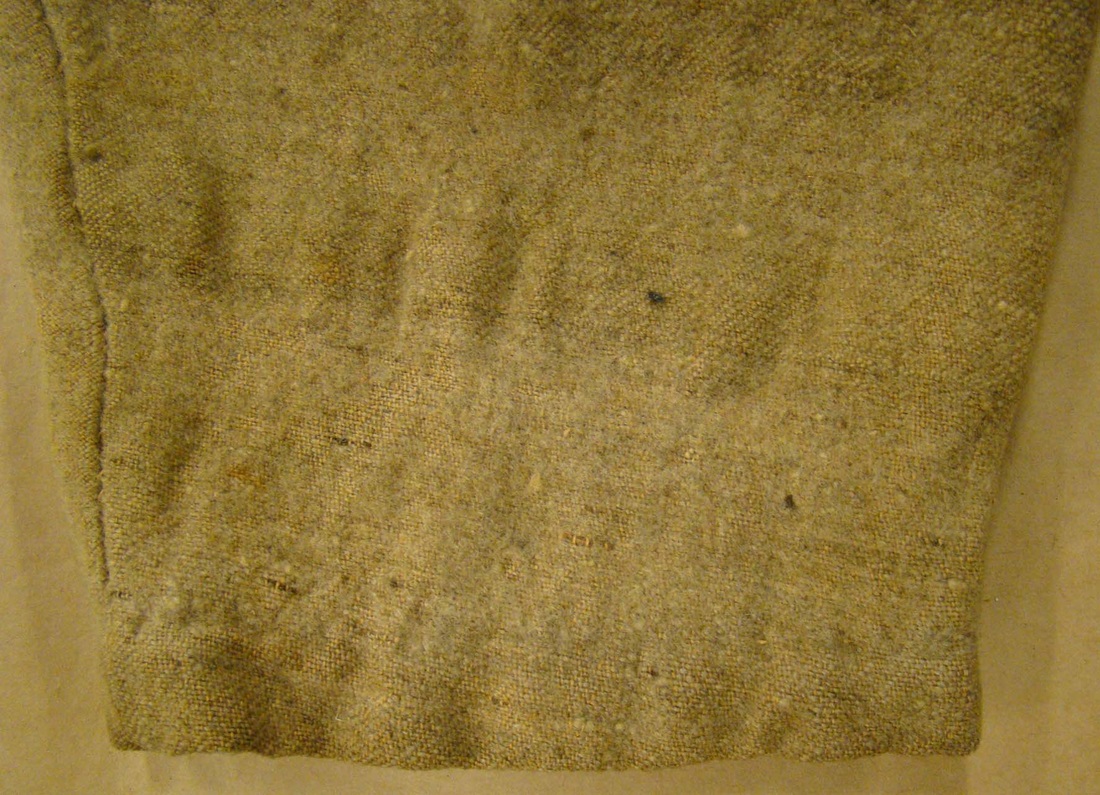

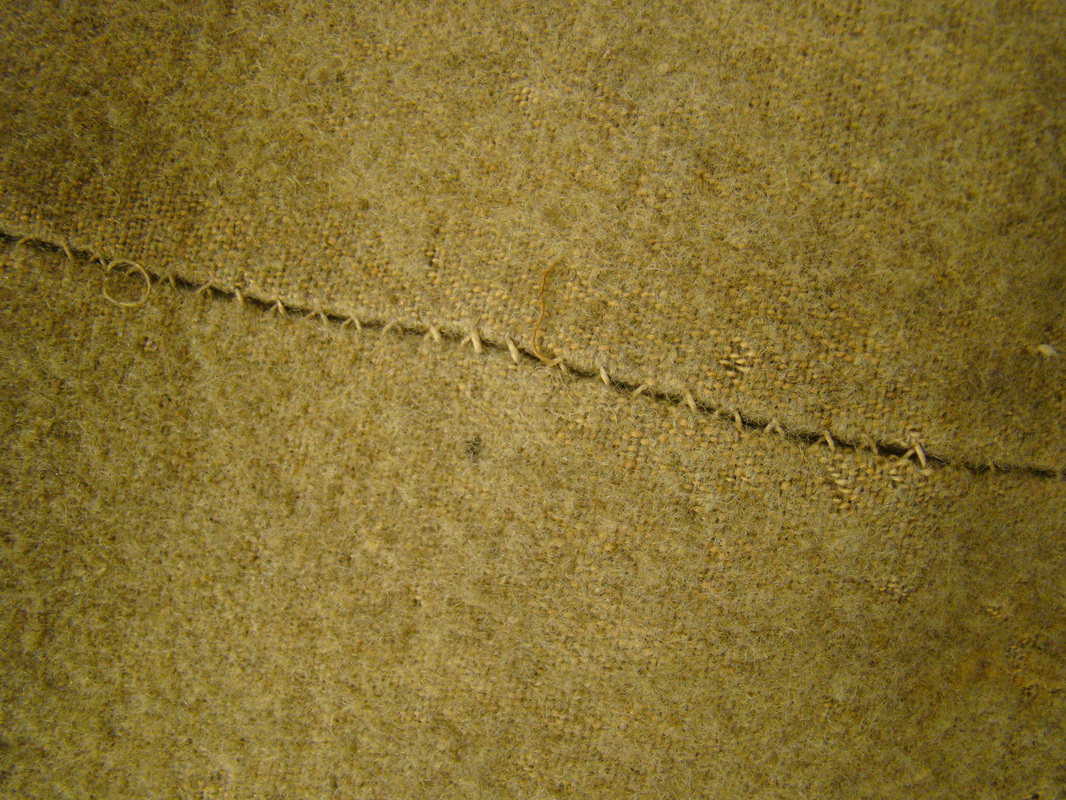

The jacket's basic fabric has a light, yellowish-tan cotton warp, and an oatmeal-gray woolen weft. There are patches of the nap on some of the surfaces. The nap has a distinctly light grayish color. From a few feet away, the basic cloth appears to a tan color, slightly brindled, due to variations in the shade of weft yarns. The collar facing fabric is typical. The woolen weft has a bright, dark blue color, and the cotton warp a light, yellowish-tan color. The buttons are missing, but one brass shank remains attached by the buttonhole thread, indicating that the jacket was issued with brass buttons that were broken off at some point, perhaps in conformance with Federal regulations that Confederate parolees remove their military buttons. The buttonholes themselves are worked with a double thread, something that was unusual for depot buttonholes. The exterior pocket is set on the right breast with the pocket welt centered between middle button and next lower button. The bottoms of the lapel fronts are distinctly squared. There is a single row of basted topstitching all around the jacket's edge, rather widely-spaced, except for the collar. The top edge of the pocket welt has a few widely spaced, basting topstitches, but the cuffs have no topstitching. The left side seam has no belt loop, nor does it appear to have ever had one. The rear bottom edge of the back, at the center seam, has a very slight point.

Hoey’s collar was misaligned when sewn in place and the bottom seam of the outer collar falls below the neck hole seamline. Such an effect was entirely unintentional on the part of the seamstress.

The interior patch pocket, set in the left breast, has a rectangular shape with the bottom corners being rounded. The opening has been folded over a quarter inch twice to make a neat edge, and felled in place. The pocket bag itself has been basted to the lining with somewhat widely spaced stitches. Both the left patch pocket and the right inset pocket are made from unbleached drillings, in contrast to the osnaburg lining.

The facing lapels also include some noteworthy characteristics. They are pieced with the bottom portions cut from scrap, but the tops employing selvedge along the interior edge. The facing lapels have been laid over the osnaburg lining and whipstitched in place, with the selvedge being sewn flat, but the raw edge of the pieced ends being folded under, and thereby losing some width.[18]

The jacket's basic fabric has a light, yellowish-tan cotton warp, and an oatmeal-gray woolen weft. There are patches of the nap on some of the surfaces. The nap has a distinctly light grayish color. From a few feet away, the basic cloth appears to a tan color, slightly brindled, due to variations in the shade of weft yarns. The collar facing fabric is typical. The woolen weft has a bright, dark blue color, and the cotton warp a light, yellowish-tan color. The buttons are missing, but one brass shank remains attached by the buttonhole thread, indicating that the jacket was issued with brass buttons that were broken off at some point, perhaps in conformance with Federal regulations that Confederate parolees remove their military buttons. The buttonholes themselves are worked with a double thread, something that was unusual for depot buttonholes. The exterior pocket is set on the right breast with the pocket welt centered between middle button and next lower button. The bottoms of the lapel fronts are distinctly squared. There is a single row of basted topstitching all around the jacket's edge, rather widely-spaced, except for the collar. The top edge of the pocket welt has a few widely spaced, basting topstitches, but the cuffs have no topstitching. The left side seam has no belt loop, nor does it appear to have ever had one. The rear bottom edge of the back, at the center seam, has a very slight point.

Hoey’s collar was misaligned when sewn in place and the bottom seam of the outer collar falls below the neck hole seamline. Such an effect was entirely unintentional on the part of the seamstress.

The interior patch pocket, set in the left breast, has a rectangular shape with the bottom corners being rounded. The opening has been folded over a quarter inch twice to make a neat edge, and felled in place. The pocket bag itself has been basted to the lining with somewhat widely spaced stitches. Both the left patch pocket and the right inset pocket are made from unbleached drillings, in contrast to the osnaburg lining.

The facing lapels also include some noteworthy characteristics. They are pieced with the bottom portions cut from scrap, but the tops employing selvedge along the interior edge. The facing lapels have been laid over the osnaburg lining and whipstitched in place, with the selvedge being sewn flat, but the raw edge of the pieced ends being folded under, and thereby losing some width.[18]

|

|

|

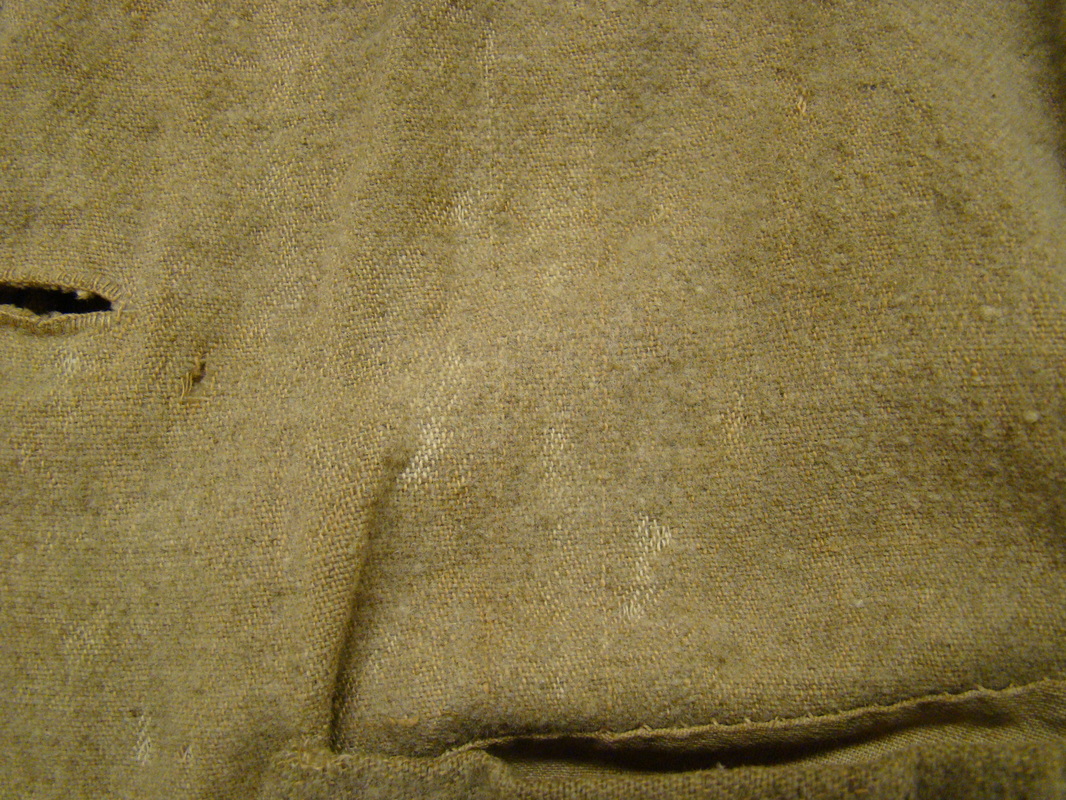

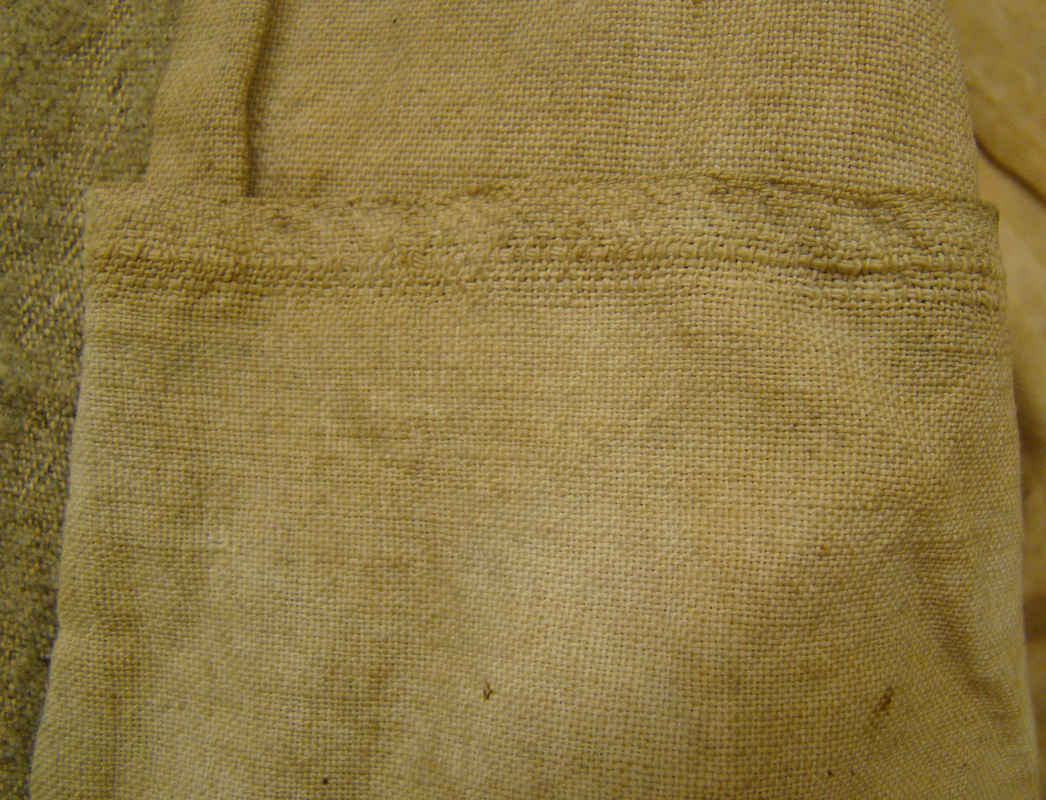

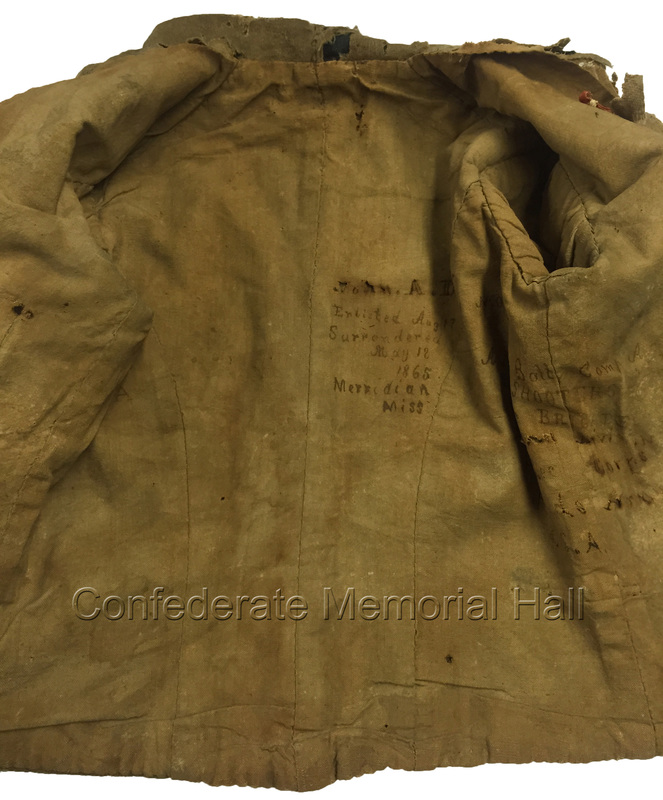

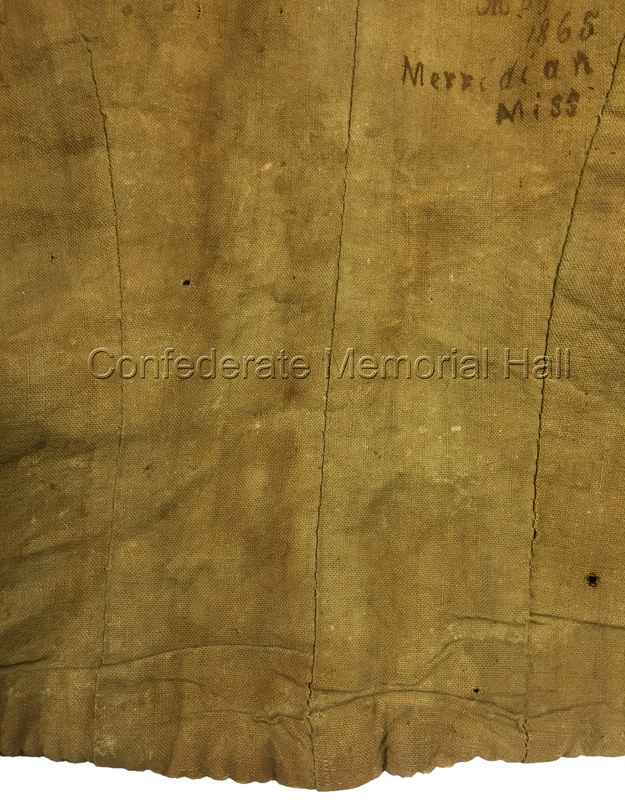

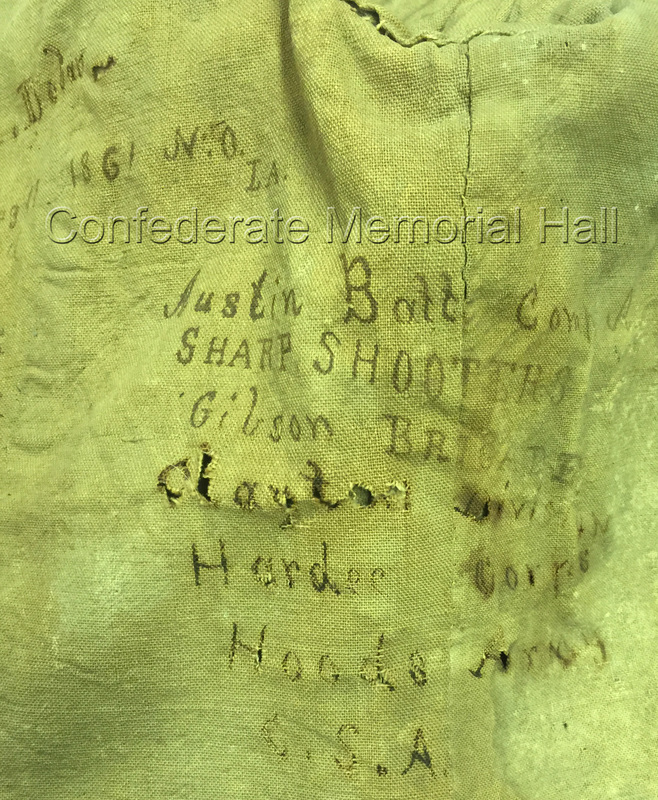

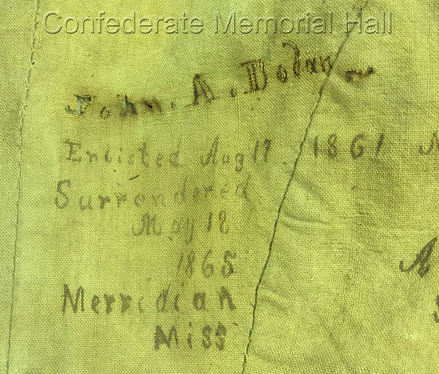

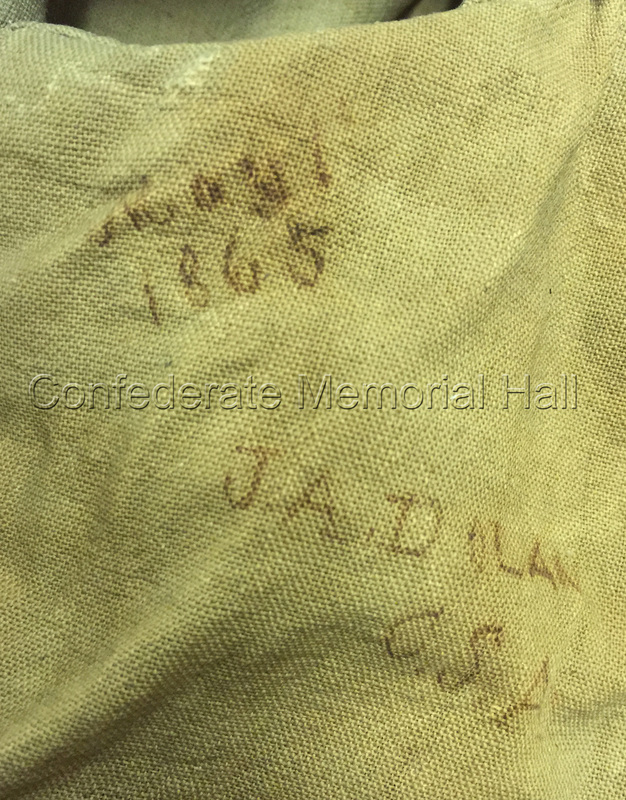

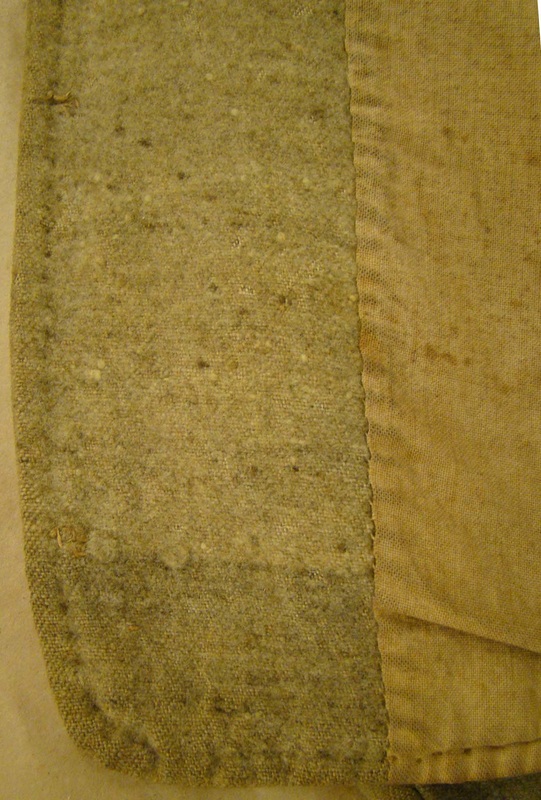

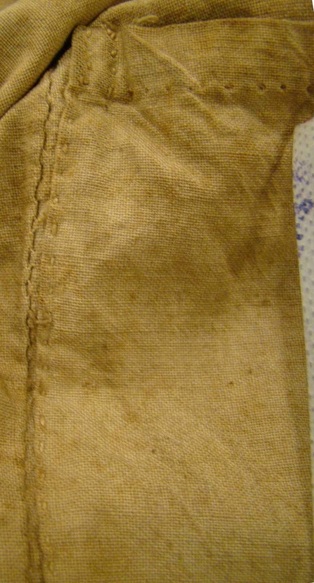

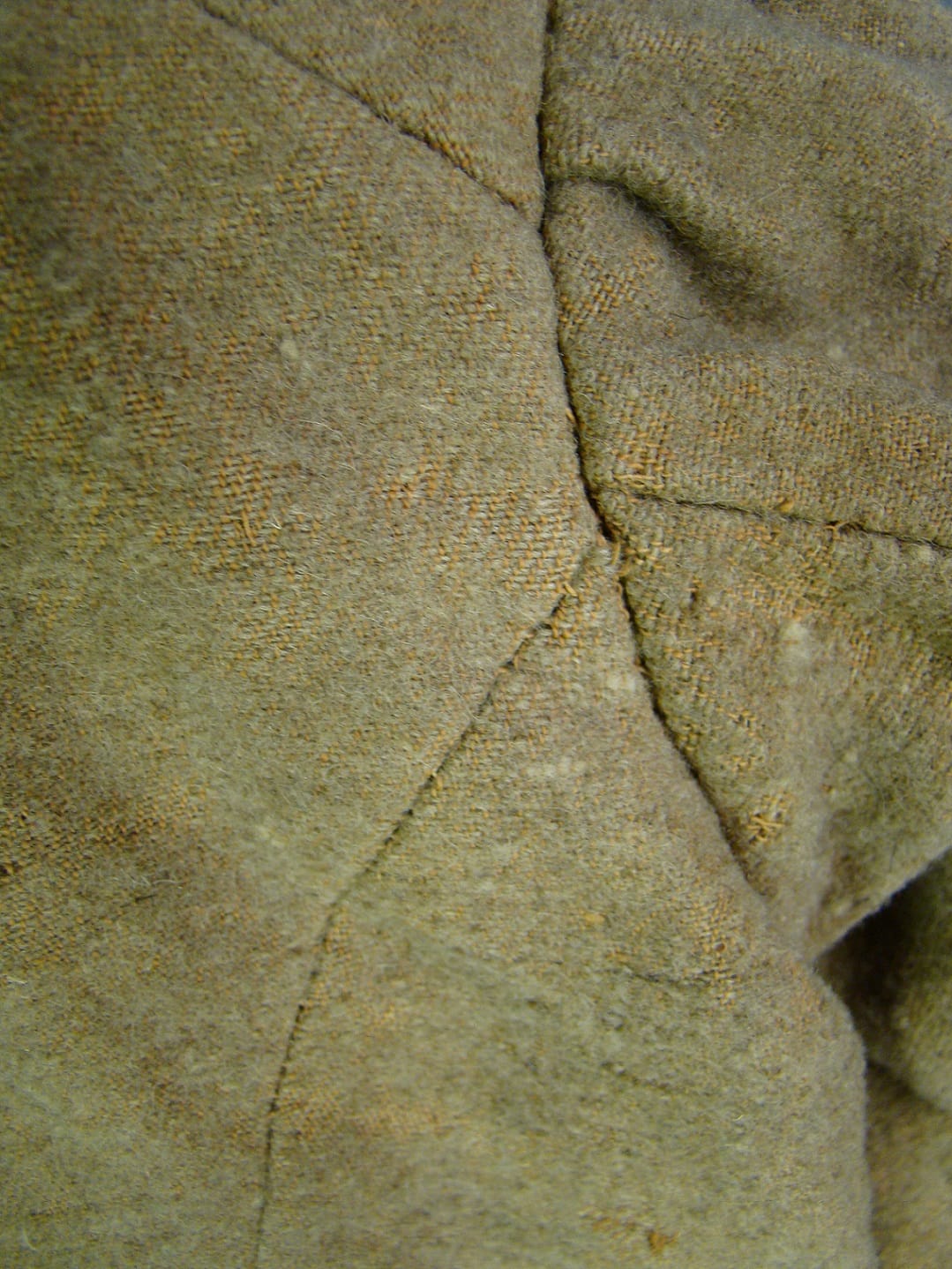

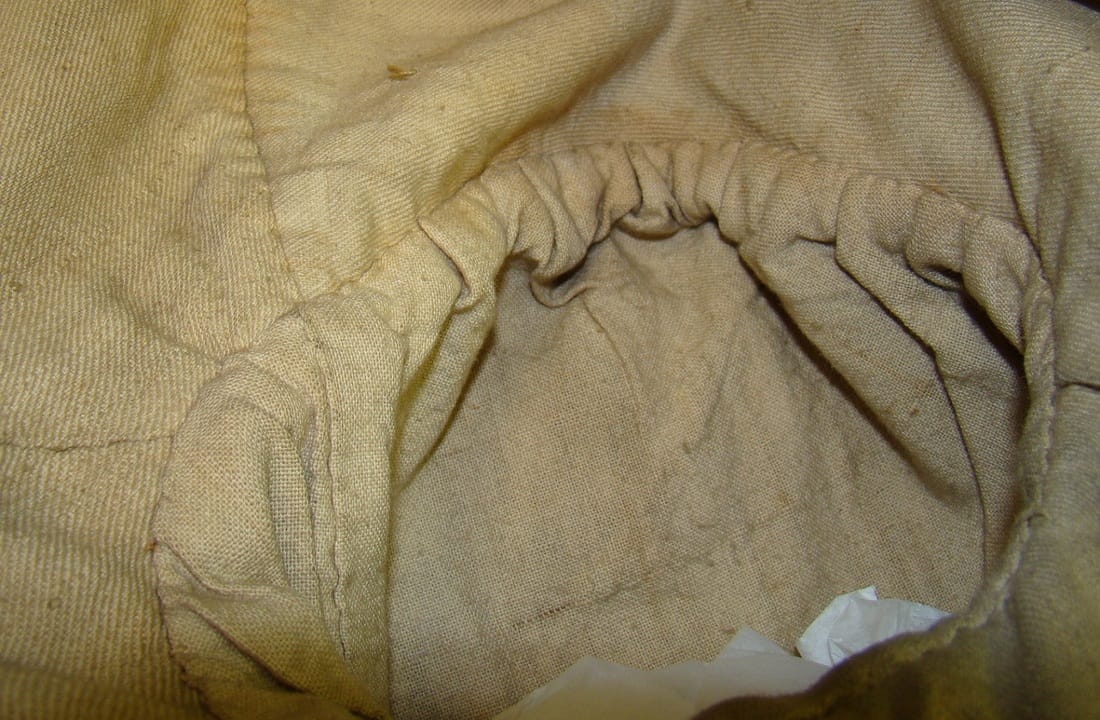

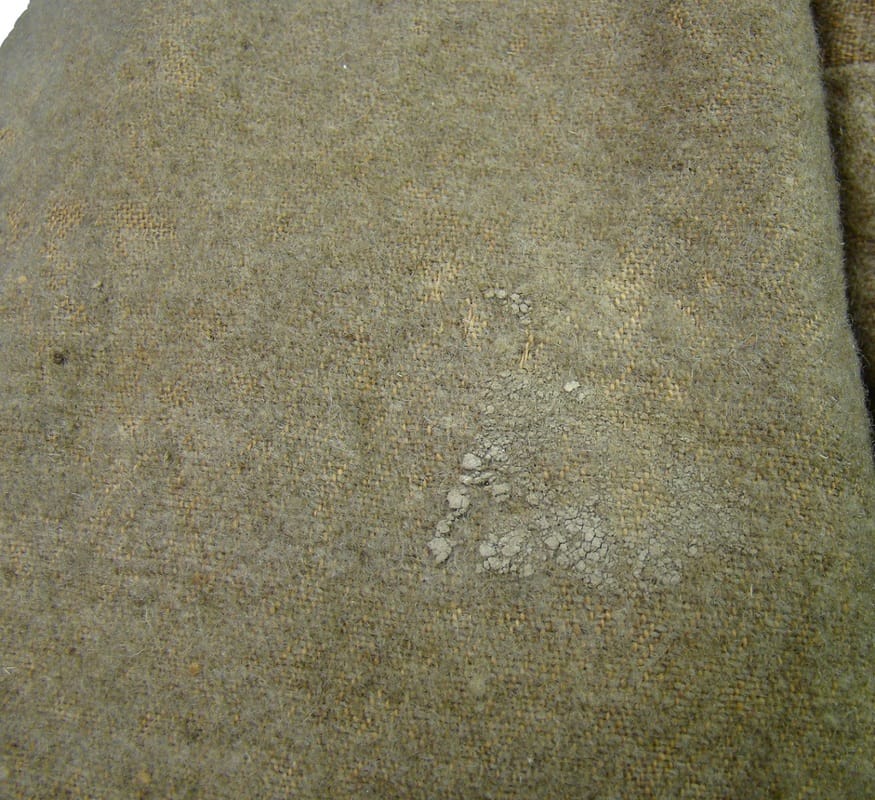

John A. Dolan’s jacket is likewise marked in the manner of Hoey’s, having the owner’s battle history and chain-of-command penned in the lining. Dolan enlisted in 1861 and fought in the Army of Tennessee through the Nashville Campaign of 1864. Following the army's retreat into Mississippi, Austin’s Battalion became part of the Mobile Garrison, and ended the war there. On May 1, 1865, Dolan drew clothing that probably included this jacket. This may have taken place at Cuba Station, Alabama, close to Meridian, where the battalion arrived on April 24th, or at Citronelle, Alabama, where the command surrendered on May 4th.[19] Dolan inscribed the lining of his jacket with many details of his service. The inscription, in three sections, reads, “John. A. Dolan, Enlisted Aug 17 1861 N.O. LA., Surrendered May 18 1865, Merridian, Miss,” “Austin Batt Comp A., SHARP SHOOTERS, Gibson BRIGADE, Clayton Division, Hardee Corps, Hoods Army, C.S.A.,” and, “May 1865, J.A. DOLAN C.S.A.”

The jacket is an overall tan color now, but the protected fabric surface can be observed through tears in the seams, and a heavy, oatmeal-colored nap is visible on pressed-down quarter inch seams. The buttons are all missing. The exterior pocket is placed on the left breast and the middle of the pocket welt is centered on middle buttonhole. The welt is topstitched with a single loose backstitch all around. The rectangular, interior patch pocket, set in the right breast, has slightly rounded bottom corners. The pocket opening employs the selvedge and is not folded over. The dark blue collar facing aligns with the neck hole seam. Dolan’s blue trim varies from the norm. It appears to be a woolen flannel with cotton warp threads interspersed at regular intervals alongside woolen warp yarns. The woolen yarns are also dyed a deeper, brighter blue than what is typically encountered. The bottoms of the lapel fronts are slightly rounded. The front edges of the lapels have a single row of topstitching (a widely spaced backstitch) that extends from the base of the collar to as far as where the facing lapel meets the lining at the bottom edge of the jacket. The bottom edge of the jacket, the cuffs and the collar have no topstitch. The jacket has a belt loop on the left side. The inside facing of the belt loop is osnaburg, and the bottom edge stitching has come loose, so that the bottom of the loop is no longer secured to the jacket.[20]

The jacket is an overall tan color now, but the protected fabric surface can be observed through tears in the seams, and a heavy, oatmeal-colored nap is visible on pressed-down quarter inch seams. The buttons are all missing. The exterior pocket is placed on the left breast and the middle of the pocket welt is centered on middle buttonhole. The welt is topstitched with a single loose backstitch all around. The rectangular, interior patch pocket, set in the right breast, has slightly rounded bottom corners. The pocket opening employs the selvedge and is not folded over. The dark blue collar facing aligns with the neck hole seam. Dolan’s blue trim varies from the norm. It appears to be a woolen flannel with cotton warp threads interspersed at regular intervals alongside woolen warp yarns. The woolen yarns are also dyed a deeper, brighter blue than what is typically encountered. The bottoms of the lapel fronts are slightly rounded. The front edges of the lapels have a single row of topstitching (a widely spaced backstitch) that extends from the base of the collar to as far as where the facing lapel meets the lining at the bottom edge of the jacket. The bottom edge of the jacket, the cuffs and the collar have no topstitch. The jacket has a belt loop on the left side. The inside facing of the belt loop is osnaburg, and the bottom edge stitching has come loose, so that the bottom of the loop is no longer secured to the jacket.[20]

3a. A front view of Dolan's jacket. The jacket is missing its buttons, which strongly suggests that they were brass Confederate buttons that Dolan had to remove in accordance with the Federal dictate. The Dolan jacket artifact, in the 3-series of images, is courtesy of Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana.

|

|

|

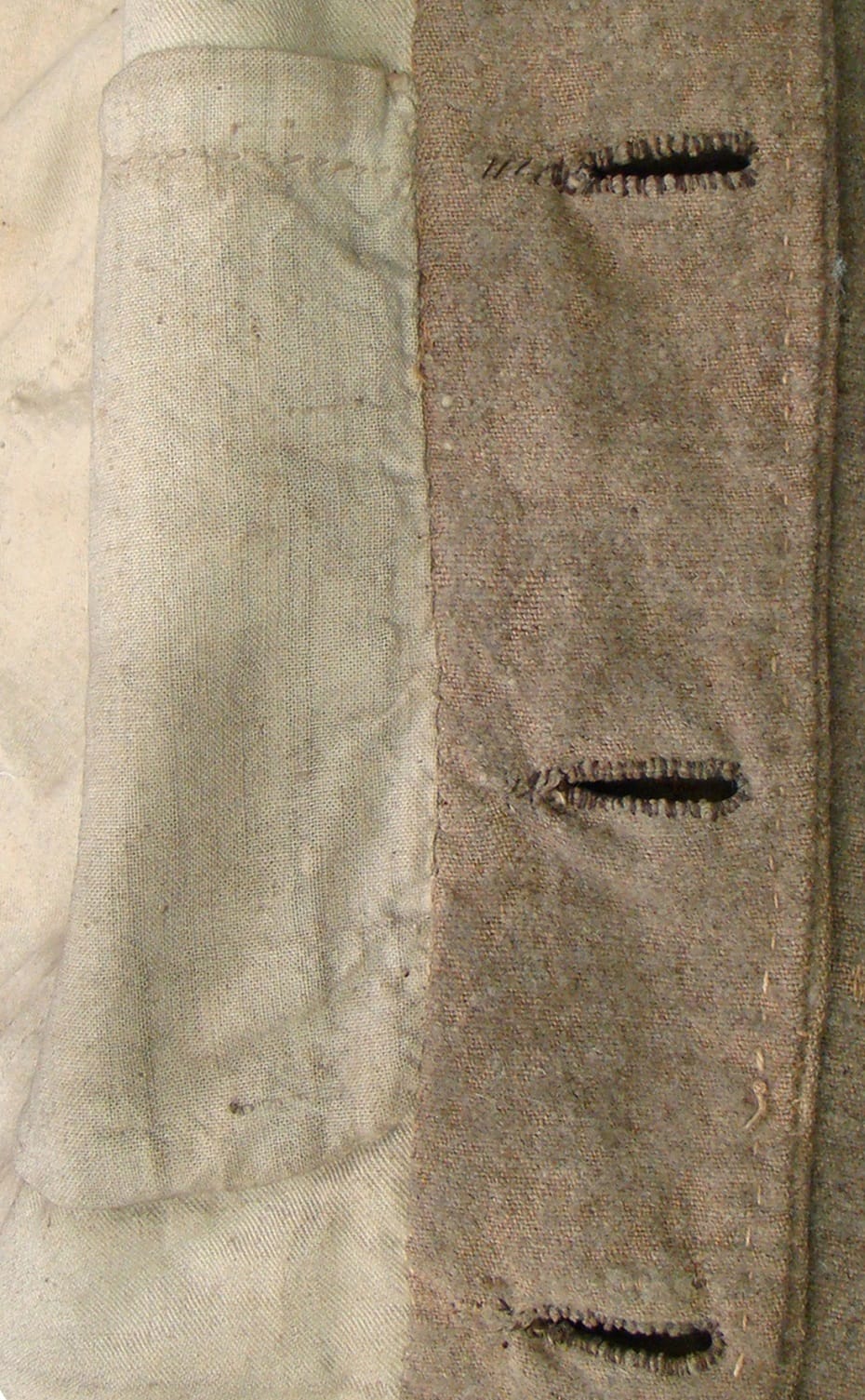

Another infantry jacket is attributed to Andrew Jackson Duncan's infantry jacket has a tentative provenance based solely upon his name (assuming this to be correct). Family lore attributes Duncan’s service to the 31st Mississippi Infantry, but the service records do not support this claim. There are three other “Andrew” or “A.J.” Duncans in the Mississippi rosters, which name matches that associated with the jacket, and these men are all affiliated with cavalry commands that served in the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana.[21] Regardless of who might actually have worn the jacket, it is authentic. The fabric has a tan-colored cotton warp, and an oatmeal-gray woolen weft. The overall color appears homogenous. The collar trim’s woolen weft has the same bright, dark blue color normally encountered, but it may have a plain weave. The trim’s cotton warp is a light tan color. The collar facing aligns with the neckhole seam. The jacket retains its wooden Allen buttons, and the bottoms of the lapel fronts are slightly squared. The exterior pocket is placed on the right breast, and the bottom edge of the welt starts at middle button, with the top of the welt above the middle button. This jacket has a double-row of topstitching all around the body, similar to that found in the Montgomery jackets. This was done in a widely spaced backstitch. The exterior pocket welt has the same widely spaced topstitching in a single row. The cuffs and collar are not topstitched, but the neck hole just beneath the base of the collar is secured with a single row of widely spaced backstitching. The jacket has a single belt loop on the left side.[22]

The last of the extant infantry jackets (to retain its blue collar) was owned by J.M. Donald (possibly McDonald) of Company I, 6th Missouri Infantry.[23] The regiment fought in the Mississippi and Vicksburg Campaigns, the Atlanta and Nashville Campaigns, and ended its service in 1865 defending Mobile. Donald probably got the jacket while at Mobile, Alabama. The fabric has a natural white cotton warp, and an oatmeal-gray woolen weft. Patches of the gray nap are still intact. The collar trim seems to conform to the usual pattern, but since it was observed behind glass while on exhibit, exact details are lacking. The woolen weft is a bright, dark blue, and the cotton warp a golden-brown. The collar facing aligns with the neck hole seam. The jacket now has two Confederate, local staff buttons.[24] The exterior pocket is set on the right breast with the middle of the pocket welt centered on the middle button. The bottoms of the lapel fronts are somewhat squared. The edge of the body has a double row of topstitching completed in a widely spaced backstitch. The cuffs have no topstitching, but the edge of the collar has a single row of a basting stitch along the top edge. The top edge of the exterior right pocket has a loose basting stitch, as well. The jacket has no belt loop on the left side.[25]

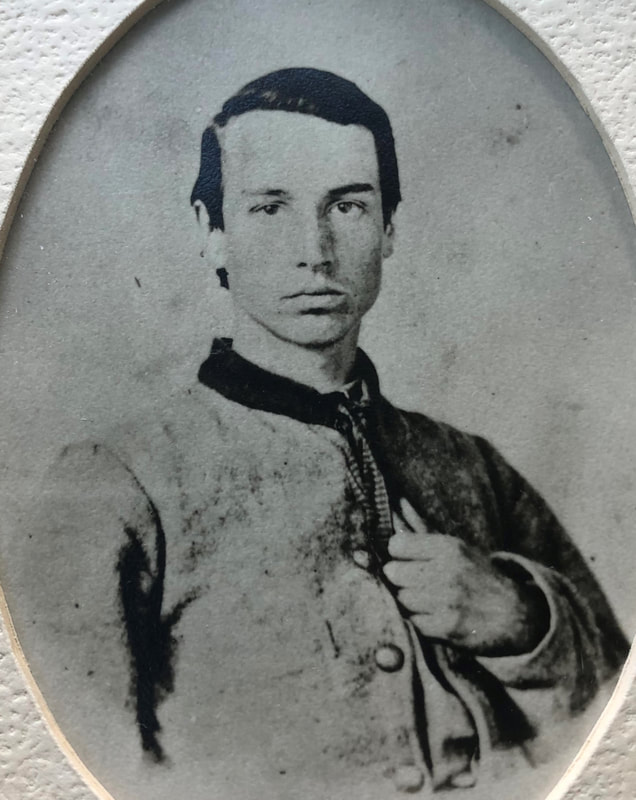

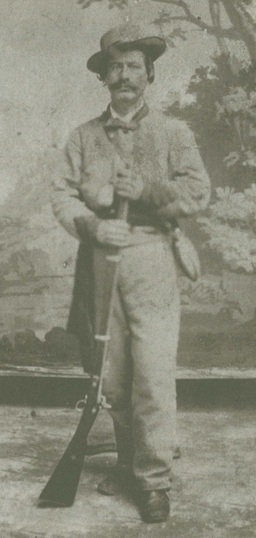

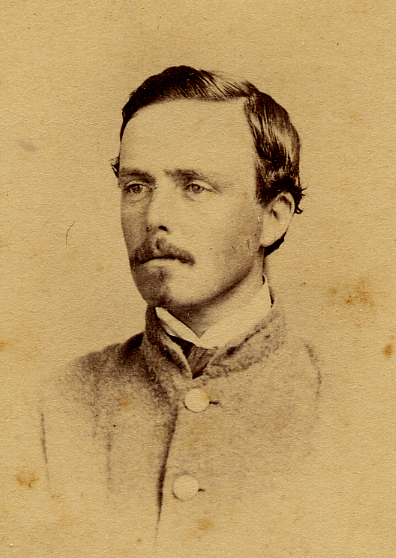

The last of the infantry jackets was worn by Silas Calmes Buck, Company D, 12th Mississippi Cavalry. Buck's jacket left the factory as a blue-trimmed, infantry jacket, but thereafter, Buck had it trimmed in mounted rifle green. Buck's wartime image of him wearing the jacket before its alteration attests to its original configuration. Buck received the jacket while serving with General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s command in the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. Buck enlisted in the 12th Mississippi Cavalry in October 1864, and at the end of the war, his regiment was at Fort Blakely. He surrendered at Citronelle on May 4, 1865, and was paroled at Gainesville, Alabama on May 14.[26] He would have received the jacket no earlier than October 1864, but more likely he got it in the spring of 1865. Perhaps the green trim was applied to a batch of uniforms within Forrest's command since the command fought as mounted infantry and green was the mounted infantry color. In any case, the jacket’s overall color is a light tan. The fabric has a light tan-colored cotton warp, and a beige woolen weft. It varies from the other Anderson jackets in that it has dark emerald green, tightly woven, light weight twill trim cloth on the collar and cuffs. The collar has been attached in the same manner as Hoey’s with the bottom seam misaligned below the top edges of the lapels either side of the collar’s ends. There is a row of basted topstitching all along the top edge, and the top seam is whipstitched to the interior facing. The bottom edge of the green collar facing is likewise whipstitched to the neck hole. The one-piece cuff trim is cut straight across, typical of that seen on the Columbus, Georgia jackets. The top edge of the cuff facing is whipstitched in place, and the bottom edge is folded under the end of the cuff, tucked under the folded under edge of the lining and whipstitched closed. The exterior pocket is placed on the right breast, and the pocket welt bottom is even with the middle button. The entire edge of the pocket welt is topstitched with a tight backstitch. The bottoms of the lapel fronts are distinctly squared. The entire edge of the jacket body is topstitched all around with a stout backstitch. The topstitching and buttonholes are of a natural white cotton thread, except for the collar topstitching that is light brown. The jacket has a single belt loop on the left side. The unbleached osnaburg lining has the typical, interior patch pocket, rectangular in shape, in the left breast. The pocket opening is folded inward and secured with a very tight backstitch. The jacket also has Mississippi “I” brass buttons instead of wooden Allen buttons. They appear to be original factory applied buttons, but they might have been added by Buck after he received the jacket.[27]

The last two surving jackets include an untrimmed jacket, and a red trimmed artillery jacket.

The untrimmed, plain variant Anderson jacket (devoid of the usual collar trim) was worn by an unidentified first lieutenant. It was donated to the State of Louisiana by the same family who donated a Richmond jacket worn by Mississippi soldier Abraham Adler. The jacket's fabric has a yellowish-white or light tan cotton warp, and an oatmeal-gray woolen weft. Some of the gray nap is still present in patches. Furthermore, the fabric has a slightly striped appearance as observed in many of the Montgomery jackets and trousers. The stripes are the result of intermittently spaced sections of lighter and darker colored fill yarn that makes up the weft. Nevertheless, the overall color appears to be tan. The outside of the collar, made of the same fabric as the rest of the jacket, aligns with the neckhole seam. Interestingly, the officer added first lieutenant bars to the collar. Not having any quarter- or eighth-inch gold braid, the officer used sixteenth-inch yellow soutache. He laid two pieces of soutache together for each bar to achieve the desired eighth-inch width. On each side, the top bar is two inches long and the bottom bar approximately two and a quarter inches long. The jacket still retains three of its Louisiana pelican buttons. These are wartime buttons and were likely added to the jacket during the war. Two are Tice number LA204A2, with the backmark “Hyde & Goodrich, New Orleans,” and with the pelican’s head facing over its right wing. The other button is Tice number LA 220A5, with the backmark “Scovill Mfg. Co. Waterbury,” and with the pelican’s head facing to the bird’s left. The buttons and the donor family’s Louisiana residence suggest that the unidentified officer was from Louisiana. The exterior pocket is on the right side. The bottom edge of exterior pocket welt is level with the middle buttonhole. The interior patch pocket, set in the left breast, has slightly rounded bottom corners. The pocket opening is folded inward and secured with a widely spaced, short basting stitch. The bottoms of the lapel fronts are slightly rounded, and the entire edge of the jacket, to include the collar, has a single row of widely spaced topstitching. The right exterior pocket welt has loose basting, topstitching along the bottom edge only, and the cuffs have no topstitching. The jacket shows no signs of having ever had a single belt loop on the left side.[28]

The untrimmed, plain variant Anderson jacket (devoid of the usual collar trim) was worn by an unidentified first lieutenant. It was donated to the State of Louisiana by the same family who donated a Richmond jacket worn by Mississippi soldier Abraham Adler. The jacket's fabric has a yellowish-white or light tan cotton warp, and an oatmeal-gray woolen weft. Some of the gray nap is still present in patches. Furthermore, the fabric has a slightly striped appearance as observed in many of the Montgomery jackets and trousers. The stripes are the result of intermittently spaced sections of lighter and darker colored fill yarn that makes up the weft. Nevertheless, the overall color appears to be tan. The outside of the collar, made of the same fabric as the rest of the jacket, aligns with the neckhole seam. Interestingly, the officer added first lieutenant bars to the collar. Not having any quarter- or eighth-inch gold braid, the officer used sixteenth-inch yellow soutache. He laid two pieces of soutache together for each bar to achieve the desired eighth-inch width. On each side, the top bar is two inches long and the bottom bar approximately two and a quarter inches long. The jacket still retains three of its Louisiana pelican buttons. These are wartime buttons and were likely added to the jacket during the war. Two are Tice number LA204A2, with the backmark “Hyde & Goodrich, New Orleans,” and with the pelican’s head facing over its right wing. The other button is Tice number LA 220A5, with the backmark “Scovill Mfg. Co. Waterbury,” and with the pelican’s head facing to the bird’s left. The buttons and the donor family’s Louisiana residence suggest that the unidentified officer was from Louisiana. The exterior pocket is on the right side. The bottom edge of exterior pocket welt is level with the middle buttonhole. The interior patch pocket, set in the left breast, has slightly rounded bottom corners. The pocket opening is folded inward and secured with a widely spaced, short basting stitch. The bottoms of the lapel fronts are slightly rounded, and the entire edge of the jacket, to include the collar, has a single row of widely spaced topstitching. The right exterior pocket welt has loose basting, topstitching along the bottom edge only, and the cuffs have no topstitching. The jacket shows no signs of having ever had a single belt loop on the left side.[28]

The last Anderson jacket is a red-trimmed artillery variant worn by Alabama artilleryman Hugh C. Clarke. It is the only surviving Anderson-style artillery jacket. Clarke served in Company D, Alabama State Reserves Artillery from September 1863 through November 1864 (the date of his last service record), and perhaps until the end of the war. He enlisted for the war as a substitute at thirty-six years of age. His command served in the Mobile area. Clarke presumably got the jacket during the last months of the war. A few things are worth noting about Clarke and his jacket. The jacket would have fit a man about five foot, six inches tall. Clarke was five foot, two inches tall, which means the jacket would have been large on him. Louisiana pelican buttons were available throughout the war, and might have been applied at the depot, which could explain why Clarke had them on his jacket. Finally, as part of the Alabama reserve troops that fell under Confederate command late in the war, Clarke would have been entitled to both Confederate and Alabama State quartermaster clothing, which would explain why Clarke had a Confederate quartermaster issue jacket.

Turning to Clarke’s jacket, the basic fabric is the same as observed in the other Anderson jackets and has an overall tan color. The fabric does not exhibit the brindling that many of these jackets have. The basic fabric's warp is a golden-yellow color, and the weft is an oatmeal-gray. The fabric’s light gray nap is present over much of the jacket’s surface. The outside of the collar aligns with the neck hole seam. The exterior pocket is on the right side. The bottom edge of exterior pocket welt is level with the middle buttonhole. The bottom corners of the front lapels are slightly rounded. The entire edge of the jacket has a single row of topstitching. The jacket's most salient feature is the red trim: including both the collar facing and the pointed cuffs. Another feature that differs from other Anderson jackets is the composition of the lining that departs from the typical, all-osnaburg material. The body lining is made of unbleached cotton drill, the sleeves and interior pocket of the usual osnaburg, and the exterior pocket bag of a coarse cotton bagging. The depot may have had some bales of drill and cut them into lining pieces, indiscriminately mixing the drill and osnaburg lining components into the jacket sets for assembly. The coarse bagging in the exterior pocket represents an economical use of scrap. The jacket may have had a belt loop at the left side seam. There are four extant, Louisiana pelican buttons remaining on the jacket, that appear to have been attached at the depot. They are Tice number LA204A2 with Hyde & Goodrich, New Orleans backmarks. The pelican is depicted frontally with its head turned over its right wing.[29]

Turning to Clarke’s jacket, the basic fabric is the same as observed in the other Anderson jackets and has an overall tan color. The fabric does not exhibit the brindling that many of these jackets have. The basic fabric's warp is a golden-yellow color, and the weft is an oatmeal-gray. The fabric’s light gray nap is present over much of the jacket’s surface. The outside of the collar aligns with the neck hole seam. The exterior pocket is on the right side. The bottom edge of exterior pocket welt is level with the middle buttonhole. The bottom corners of the front lapels are slightly rounded. The entire edge of the jacket has a single row of topstitching. The jacket's most salient feature is the red trim: including both the collar facing and the pointed cuffs. Another feature that differs from other Anderson jackets is the composition of the lining that departs from the typical, all-osnaburg material. The body lining is made of unbleached cotton drill, the sleeves and interior pocket of the usual osnaburg, and the exterior pocket bag of a coarse cotton bagging. The depot may have had some bales of drill and cut them into lining pieces, indiscriminately mixing the drill and osnaburg lining components into the jacket sets for assembly. The coarse bagging in the exterior pocket represents an economical use of scrap. The jacket may have had a belt loop at the left side seam. There are four extant, Louisiana pelican buttons remaining on the jacket, that appear to have been attached at the depot. They are Tice number LA204A2 with Hyde & Goodrich, New Orleans backmarks. The pelican is depicted frontally with its head turned over its right wing.[29]

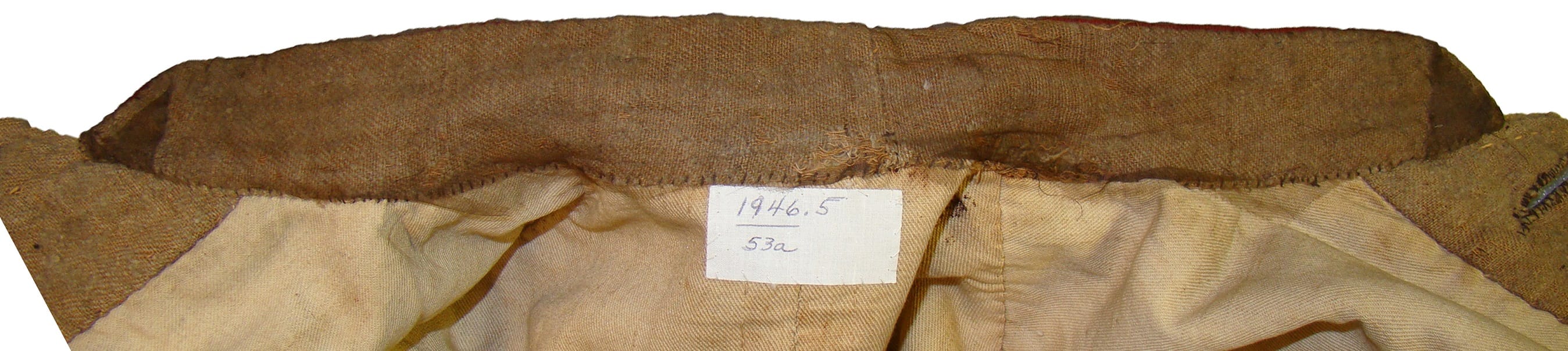

70z. The inside of the collar displays the bottom closure: the unfinished edge laid on top of the lining and whipstitched in place. Another unusual feature of the interior collar facing is that the two component pieces do not match. One was cut longer than the other and its middle seam does not align with the back lining seam.

Numerous images depicting soldiers wearing the Anderson style jacket further document and add to the data about the depot’s uniforms. The photographs include not only the infantry jacket with the dark blue, they provide evidence for other variants, as well. These include the untrimmed variant, red-faced artillery jackets, and infantry variants with pointed cuff trim. These are recounted herein, starting with images of the more common infantry jacket.

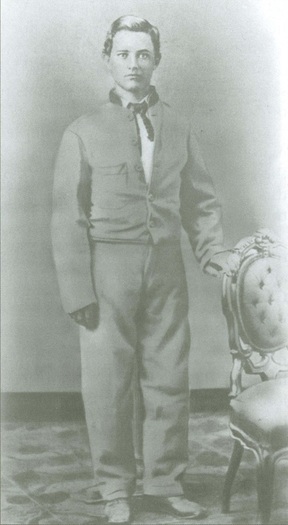

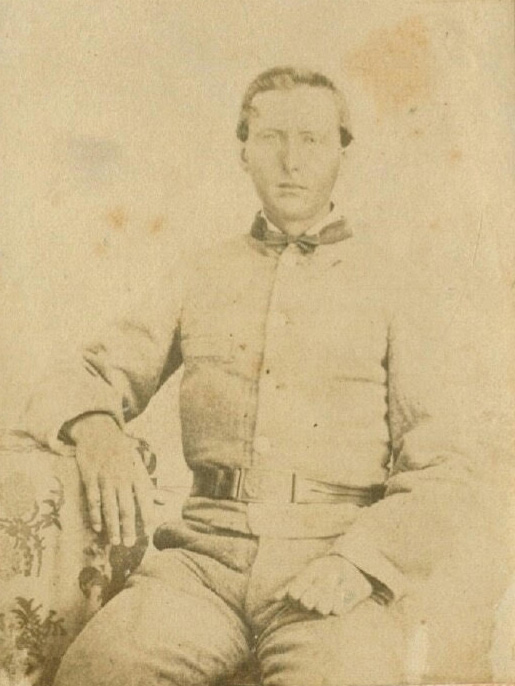

F.M. Lassiter, who served with Company I, 28th Mississippi Cavalry in the Department of Mississippi, Alabama and East Louisiana, wore one of the simple infantry jackets.[30] His full-length portrait shows that the fabric and color of the jacket and pants match. The dark blue facing aligns with the collar seam. His jacket has five wooden buttons and the exterior pocket on the right breast, with the pocket welt centered on the middle button. The bottoms of the front lapels are square-shaped.[31] Lassiter was in a disabled camp near Meridian, Mississippi during the last months of the war. He probably received the uniform there while awaiting his discharge due to being permanently disabled from a severe wound.

An unidentified Confederate, who had his picture taken by Ben Oppenheimer of Mobile in May 1865, wore the typical infantry jacket, as well. The jacket’s lapel bottoms are pointed. The collar, that appears to be dark blue, aligns with the collar seam. The image is very light and the buttons are indistinct, but they are so light that they are probably brass. The exterior pocket appears to be on the right side. The trousers and cap match the jacket. The cap is fortuitously held at an angle where the visor is clearly visible, and it resembles the Crews style that has an Alabama provenance. The cap appears to have brass buttons.[32]

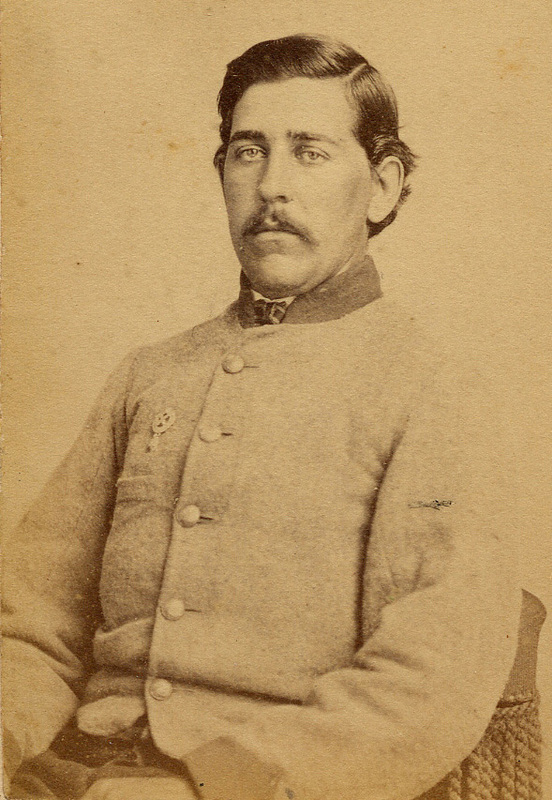

Sergeant Joseph H. Orillion, Company I, 30th Louisiana Infantry wears a noteworthy variant of the Anderson infantry jacket in an image taken by Ben Oppenheimer of Mobile in May 1865. Orillion had fought in the campaigns of Baton Rouge and Port Hudson; Atlanta and Tennessee; and, finally in 1865, Mobile.[33] The jacket has the usual dark blue collar, but the sleeves have matching pointed cuffs. It cannot be stated whether the cuff facings were applied at the factory or added after the jacket was issued. The buttons are brass, but otherwise, the image is too indistinct to see which side of the jacket that the exterior pocket is on. The bottom of lapels are also not visible in the image. The trousers match the jacket in color and material.[34]

F.M. Lassiter, who served with Company I, 28th Mississippi Cavalry in the Department of Mississippi, Alabama and East Louisiana, wore one of the simple infantry jackets.[30] His full-length portrait shows that the fabric and color of the jacket and pants match. The dark blue facing aligns with the collar seam. His jacket has five wooden buttons and the exterior pocket on the right breast, with the pocket welt centered on the middle button. The bottoms of the front lapels are square-shaped.[31] Lassiter was in a disabled camp near Meridian, Mississippi during the last months of the war. He probably received the uniform there while awaiting his discharge due to being permanently disabled from a severe wound.

An unidentified Confederate, who had his picture taken by Ben Oppenheimer of Mobile in May 1865, wore the typical infantry jacket, as well. The jacket’s lapel bottoms are pointed. The collar, that appears to be dark blue, aligns with the collar seam. The image is very light and the buttons are indistinct, but they are so light that they are probably brass. The exterior pocket appears to be on the right side. The trousers and cap match the jacket. The cap is fortuitously held at an angle where the visor is clearly visible, and it resembles the Crews style that has an Alabama provenance. The cap appears to have brass buttons.[32]

Sergeant Joseph H. Orillion, Company I, 30th Louisiana Infantry wears a noteworthy variant of the Anderson infantry jacket in an image taken by Ben Oppenheimer of Mobile in May 1865. Orillion had fought in the campaigns of Baton Rouge and Port Hudson; Atlanta and Tennessee; and, finally in 1865, Mobile.[33] The jacket has the usual dark blue collar, but the sleeves have matching pointed cuffs. It cannot be stated whether the cuff facings were applied at the factory or added after the jacket was issued. The buttons are brass, but otherwise, the image is too indistinct to see which side of the jacket that the exterior pocket is on. The bottom of lapels are also not visible in the image. The trousers match the jacket in color and material.[34]

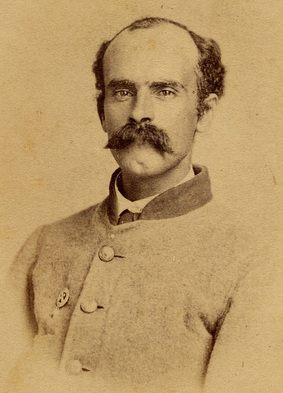

William Cummings, Company I, 3rd Missouri Infantry wears the typical Anderson infantry jacket with five, highly polished, large brass buttons. The exterior pocket is on the right breast with the horizontal welt evenly spaced between the middle and second button from the top. The bottom lapels are square-shaped. The pants fabric matches the jacket in color and texture. Cummings was captured at Fort Blakely, imprisoned at Ship Island, and released on May 1, 1865.[35] Cummings probably received his matching soldier suit shortly before the Battle of Fort Blakely. The image was undoubtedly taken soon after he was released from prison.

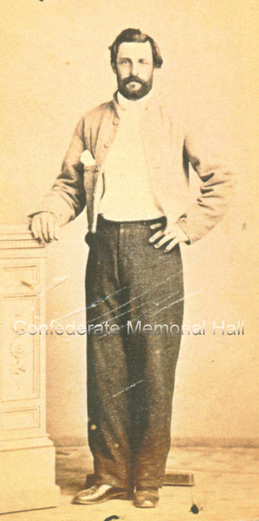

An example of the plain Anderson jackets, devoid of colored facings, is worn by Andrew Swain, 5th Company, Washington Artillery (Louisiana). Swain’s image with the jacket was taken by Anderson of New Orleans, May 1865.[36] This battery performed its last service at Mobile. The jacket has wooden Allen buttons, and the exterior pocket is on the right side, with the welt even with the middle button. The trousers appear a dark color, and are very possibly cadet gray (not uncommon for soldiers stationed at Mobile).[37]

Corresponding with the original, red-trimmed artillery jacket in the Pink Palace Museum collection, at least four images show Anderson jackets with what appears to be red facings. This assumption is reinforced by the provenance to artillery commands that the wearers’ have. The pictured jackets have red collar and cuff trim, the cuffs being pointed. A diary account also describes artillery jackets with red facings used in the department. J.L.J.W. Lear, 1st Tennessee Heavy Artillery, recalled his command being issued new uniforms with red collars and cuffs in March 1864 while stationed at Fort Morgan, near Mobile.[38] While Leer’s uniform might have come from Columbus, Georgia, it is more likely that it would have come from either Columbus, Mississippi or the Montgomery-Selma operations since those were the depots that supplied the Mobile garrison. Of the latter operations, Anderson’s Columbus, Mississippi Depot is the logical choice since evidence abounds that he usually trimmed his jackets with colored facings.

Private Henry Weston Fairchild of Fenner’s Louisiana Light Artillery Battery wears such an artillery jacket in a CDV. The CDV was taken by Ben Oppenheimer in Mobile, Alabama, probably soon after Fairchild’s command was surrendered at Citronelle, Alabama on May 4, 1865.[39] The jacket has a distinctly lighter shade of facings than are apparent in CDVs of infantry jackets: presumably red in color. The collar and cuffs have facings, the cuffs being pointed. The collar facing aligns with the collar seam. The jacket’s buttons are brass. The bottoms of the lapels are form corners. The exterior pocket is on the right side with the top of the pocket welt even with middle button and the bottom of the welt below the middle button. The trousers do not match the jacket in color and material. They are of a rougher material and a slightly darker shade.

An example of the plain Anderson jackets, devoid of colored facings, is worn by Andrew Swain, 5th Company, Washington Artillery (Louisiana). Swain’s image with the jacket was taken by Anderson of New Orleans, May 1865.[36] This battery performed its last service at Mobile. The jacket has wooden Allen buttons, and the exterior pocket is on the right side, with the welt even with the middle button. The trousers appear a dark color, and are very possibly cadet gray (not uncommon for soldiers stationed at Mobile).[37]

Corresponding with the original, red-trimmed artillery jacket in the Pink Palace Museum collection, at least four images show Anderson jackets with what appears to be red facings. This assumption is reinforced by the provenance to artillery commands that the wearers’ have. The pictured jackets have red collar and cuff trim, the cuffs being pointed. A diary account also describes artillery jackets with red facings used in the department. J.L.J.W. Lear, 1st Tennessee Heavy Artillery, recalled his command being issued new uniforms with red collars and cuffs in March 1864 while stationed at Fort Morgan, near Mobile.[38] While Leer’s uniform might have come from Columbus, Georgia, it is more likely that it would have come from either Columbus, Mississippi or the Montgomery-Selma operations since those were the depots that supplied the Mobile garrison. Of the latter operations, Anderson’s Columbus, Mississippi Depot is the logical choice since evidence abounds that he usually trimmed his jackets with colored facings.

Private Henry Weston Fairchild of Fenner’s Louisiana Light Artillery Battery wears such an artillery jacket in a CDV. The CDV was taken by Ben Oppenheimer in Mobile, Alabama, probably soon after Fairchild’s command was surrendered at Citronelle, Alabama on May 4, 1865.[39] The jacket has a distinctly lighter shade of facings than are apparent in CDVs of infantry jackets: presumably red in color. The collar and cuffs have facings, the cuffs being pointed. The collar facing aligns with the collar seam. The jacket’s buttons are brass. The bottoms of the lapels are form corners. The exterior pocket is on the right side with the top of the pocket welt even with middle button and the bottom of the welt below the middle button. The trousers do not match the jacket in color and material. They are of a rougher material and a slightly darker shade.

Three images taken by Anderson of New Orleans depict members of the 5th Company Washington Artillery wearing red-trimmed Anderson jackets. All of these images would have been taken after the 5th Company surrendered at Citronelle, Alabama in May 1865. Corporal Alex P. Allain wears an artillery jacket identical to Fairchild’s, to include having brass buttons, and red facings of collar and pointed cuffs. A.J. Chalaron wears the same type of jacket, but only the upper portion is visible. It too, has brass buttons. Likewise, John J. Jamison where’s this type of jacket with brass buttons, also with only the upper portion visible.[40] All three jackets have collar facings that aligns with the collar seam line. Allain’s and Chalaron’s images show that the exterior pocket is on the right side, and in both cases the bottom of the pocket welt is positioned slightly above the middle buttonhole.[41] What is especially interesting about Chalaron’s jacket is that he not only had this enlisted jacket devoid of his officer collar rank, he also had a fine, double-breasted officer frock coat. Furthermore, both Allain and Chalaron appear to be a bit older than their 1865 ages might suggest, and the images might well date to several years after the war, with the original Anderson-style jacket being worn as a photographer’s prop in both images.

See continuation of this study in Part II: The Jackets of Captain William M. Gillaspie’s Depot, Selma and Montgomery, Alabama. Click here to navigate to the next part...

Acknowledgements:

The author extends his thanks to numerous institutions and people for their generous cooperation and indispensable help with this study. Les Jensen’s Survey of Government Made Confederate Jackets, published in 1989, provided the first study of the “Alabama” (Anderson-style) jackets. Harold S. Wilson’s Confederate Industry provided an understanding for clothing bureau operations. Tom Arliskas’s Cadet Gray and Butternut Brown provided invaluable insights on the uniforms. Numerous institutions and individuals have shared their collections, insights, and valuable time with me to make the study possible. These include The Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, Chief Curator, Robert Hancock; Alabama Confederate Memorial Park, Marbury, Alabama, Director Bill Rambo; Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama, Bob Bradley and Dr. Kerr; Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Executive Director Ray Richey; Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana, Director Pat Ricci; Washington Artillery of New Orleans website and Glen C. Cangelosi collection; Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana, Chief Curator Wayne Phillips; Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia, Curator Heather Beattie; Museum of Southern History, Houston Baptist University, Houston, Texas, Curator Maggie Brown; General Sweeny’s Civil War Museum, Republic, Missouri, Dr. Tom Sweeney and Joseph Furtak; Wilson Creek National Battlefield, Republic, Missouri, Curators Deborah Wood and Alan Chilton; Gettysburg National Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Curator Paul Shevchuk; Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, Curator Margaret Vining; South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina, Curator Joe Long; Neill Rose, Camden, South Carolina; Alan Hoeweller collection, Cincinnati, Ohio; Samuel P. Higginbotham II collection, Orange, Virginia; Lawrence T. Jones III, Confederate Calendar, Austin, Texas; Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III collection, Dallas, Texas; Old Courthouse Museum, Vicksburg, Mississippi, Gordon A. Cotton and Jeff T. Giambrone; J.S. Mosby Antiques & Artifacts, Orange, Virginia, Stephen W. Sylvia; Historian Mike Bailey, Fort Morgan Historic Site, Gulf Shores, Alabama; Collecting the Confederate Soldier, Jim Osborn, Rockywood Productions, Inc., Denver, Colorado, 1996, Richard Todd collection; Archivist Vicki Betts, University of Texas, Tyler, online newspapers; Washington Memorial Library, Macon, Georgia, Brett Boyd and Anne Rogers; Military Images, Editor Ron Coddington, Arlington, Virginia; North South Trader Civil War, Publisher Steve Sylvia, Orange, Virginia; the Pink Palace Museum, Memphis, Tennessee, Registrar Tamara Braithwaite; and, a most generous, private collector who wishes to remain anonymous.

Copyright:

All photos are copyrighted to Adolphus Confederate Uniforms. Although the artifacts are credited to different institutions, the images themselves are the property of the website and may not be reproduced without the author’s consent.

Bibliography:

[1] Wilson, Harold S., Confederate Industry: Manufacturers and Quartermasters in the Civil War, University of Mississippi Press, Jackson, 2002, (hereafter, Wilson), pp. 103-104, n. 32 and 33; and 207, n. 127.

[2] Wilson, pp. 67 and 315, note 87, February 3, 1862; note 89, April 14, 1863, and, note 90, April 15, 1863; and, pp. 124 and 329, note 148, October 14, 1863.

[3] Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers from the State of Louisiana, Microfilm Publication 320, Roll 199, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, National Archives, Washington D.C., (hereafter, CSRs Louisiana, or other state as appropriate), service records of Thomas Taylor, 8th Louisiana Infantry, Special Requisition, received at Montgomery, Alabama, 24 November 1863, of Captain A.P. Calhoun AQM, for linsey, shirting and drilling fabrics. Taylor used these materials in a jacket that has been preserved in the Museum of the Confederacy collection. Les Jensen described the fabrics in Taylor’s jacket in the booklet, A Catalogue of Uniforms in the Collection of the Museum of the Confederacy, The Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, 2000, pp. 51 & 56: the linsey being a brownish-gray wool and cotton twill; the shirting being a brown cotton striped lining in the body; and, the drilling being an unbleached cotton drill lining the sleeves.