Confederate Uniforms of the Lower South, Part I: Tennessee, East Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama

by Fred Adolphus, June 29, 2019

The Lower South, roughly speaking, was the region that comprised South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida and Louisiana. This study will describe how the region clothed Confederate troops and the uniforms that it issued to them. The story begins with how Southern authorities organized the region’s resources to accomplish this task.

Soon after the war began, the thoughtful leadership of the South realized that the government needed to supply its armies with clothing. The individual soldiers, their families, and even philanthropic organizations could not do this alone. None had the resources equal to this task except for the government. Two systems were adopted to cope with this need: a government depot system and a system of reimbursement, called commutation. Both systems functioned alongside each other, but the reimbursement system that required either individuals or organizations to supply soldier’s clothing proved ineffective. The Confederate congress abolished the commutation system on October 8, 1862; thereby, making the Confederate quartermaster department solely responsible for clothing Confederate troops. By that time, the quartermaster depots were fully operational, so this posed no problem. In fact, the commutation system was wrought with inefficiency and fostered unhealthy speculation for scarce resources: resources that needed to be managed and properly distributed.[1] It also wasted intangible resources such as time and energy on a procurement process where government agents were routinely underbid. Finally, the clothing industry that grew out of this system victimized workers with low wages in rapidly inflating currency. This exploitation hampered both morale and support for the war effort. Had the war lasted but a year or two, the commutation system might have been the lesser evil to establishing an expensive government production apparatus. In any case, within a few months the war’s outbreak, Southern leadership began contracting for clothing to adequately supply its armies with clothing, especially for the impending winter months.

Early efforts to provide clothing drew on the resources of the Confederate quartermaster, state governments, small factories and volunteer aid societies. Special attention was given to fostering the establishment of manufacturing facilities, and the Western Confederacy had had several operations that provided a good start in this regard. Indeed, there was already a burgeoning textile industry there by the start of the war. This consisted of numerous small, privately-owned factories or mills in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi, that produced cotton and woolen yarns, and fabrics. These small factories provided cloth or finished clothing for the military once the war began, and they formed the backbone of the Confederacy’s clothing industry in the Lower South early in the war. This was especially the case when the large industrial centers at Nashville, Tennessee, and New Orleans, Louisiana fell to the enemy within the first year of the war. Additionally, nearly every state in the region had a state-operated penitentiary mill that fabricated cloth. These combined resources offered a source of clothing materials that the Confederate quartermaster could draw upon.

The first operation to consider would be the region’s chief manufacturing centers of New Orleans and Nashville. These cities provide insights into the Lower South’s capabilities and intent for the efficient manufacture of clothing. Regrettably, both places fell to enemy forces relatively early in the war, and quartermasters had to re-establish these operations elsewhere, beginning on a smaller scale.[2] Nashville, which is technically in the Upper South, figures largely into this study because its operation supplied troops from the Lower South, and when the city was captured, its operations were all shifted to the Lower South in Georgia and Mississippi.

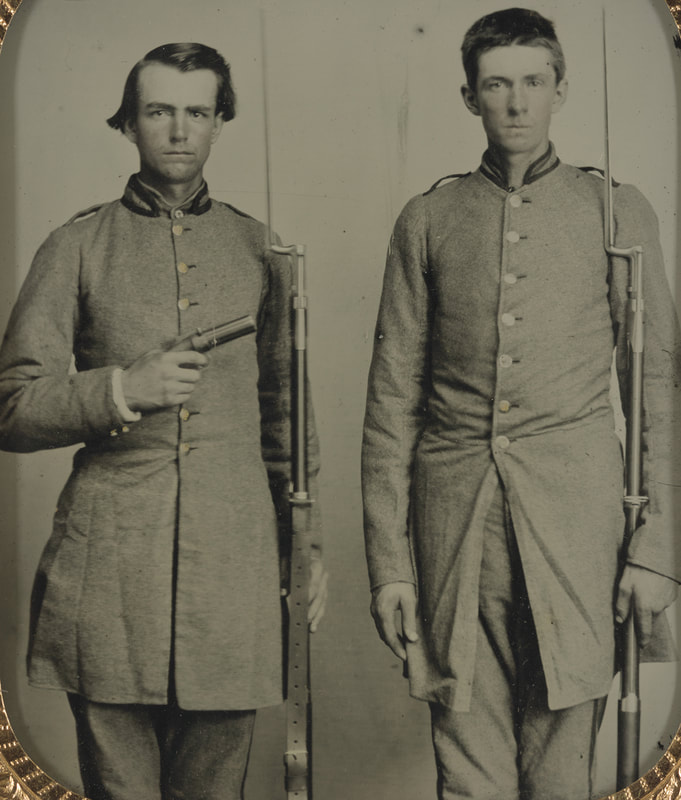

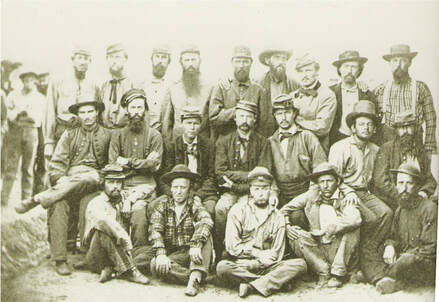

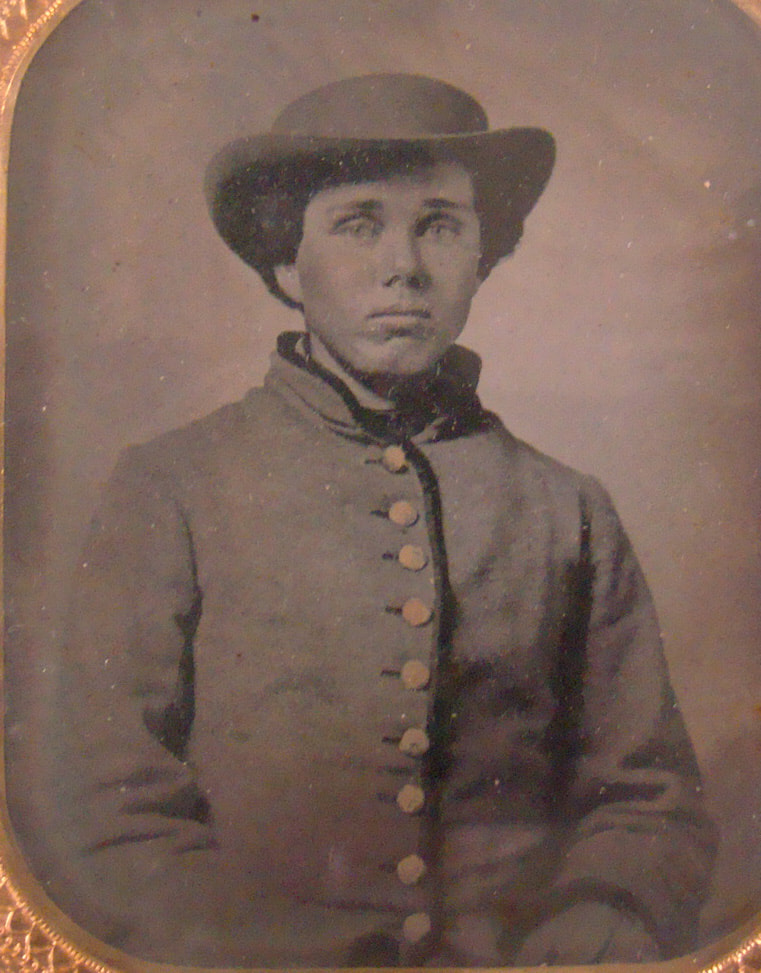

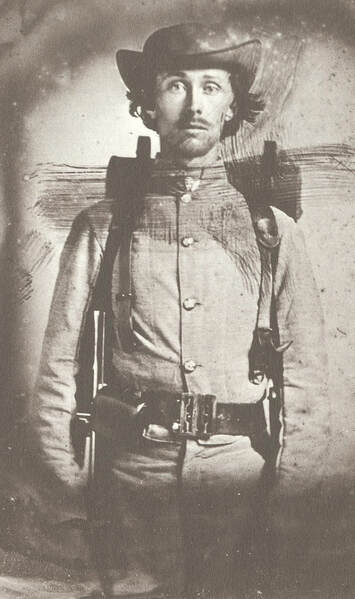

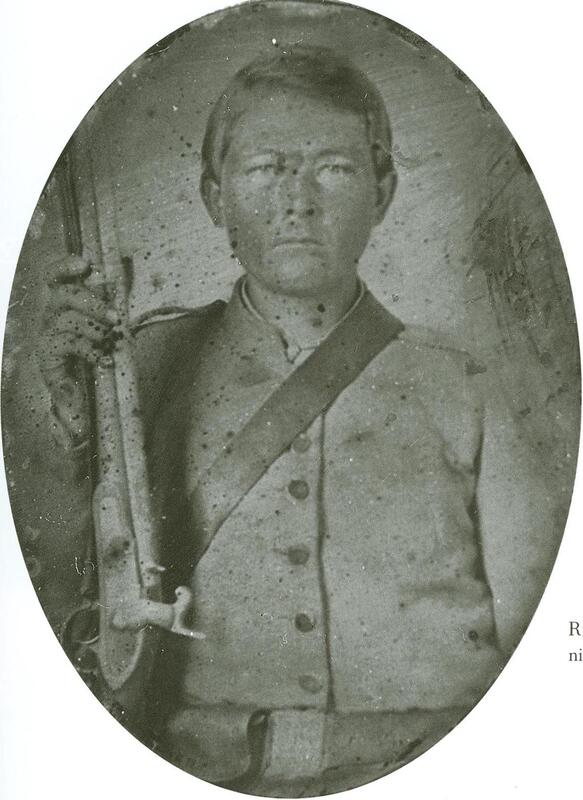

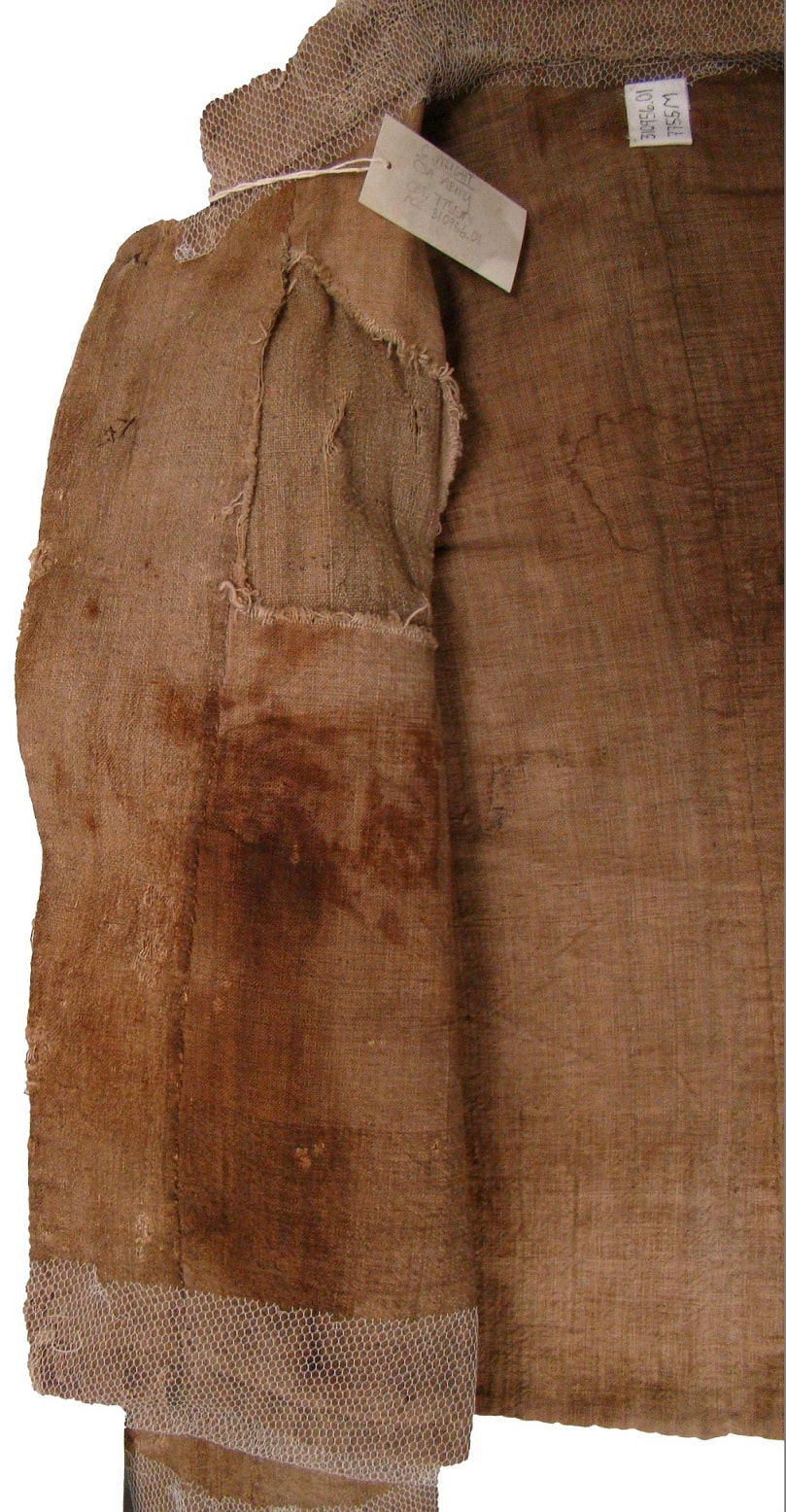

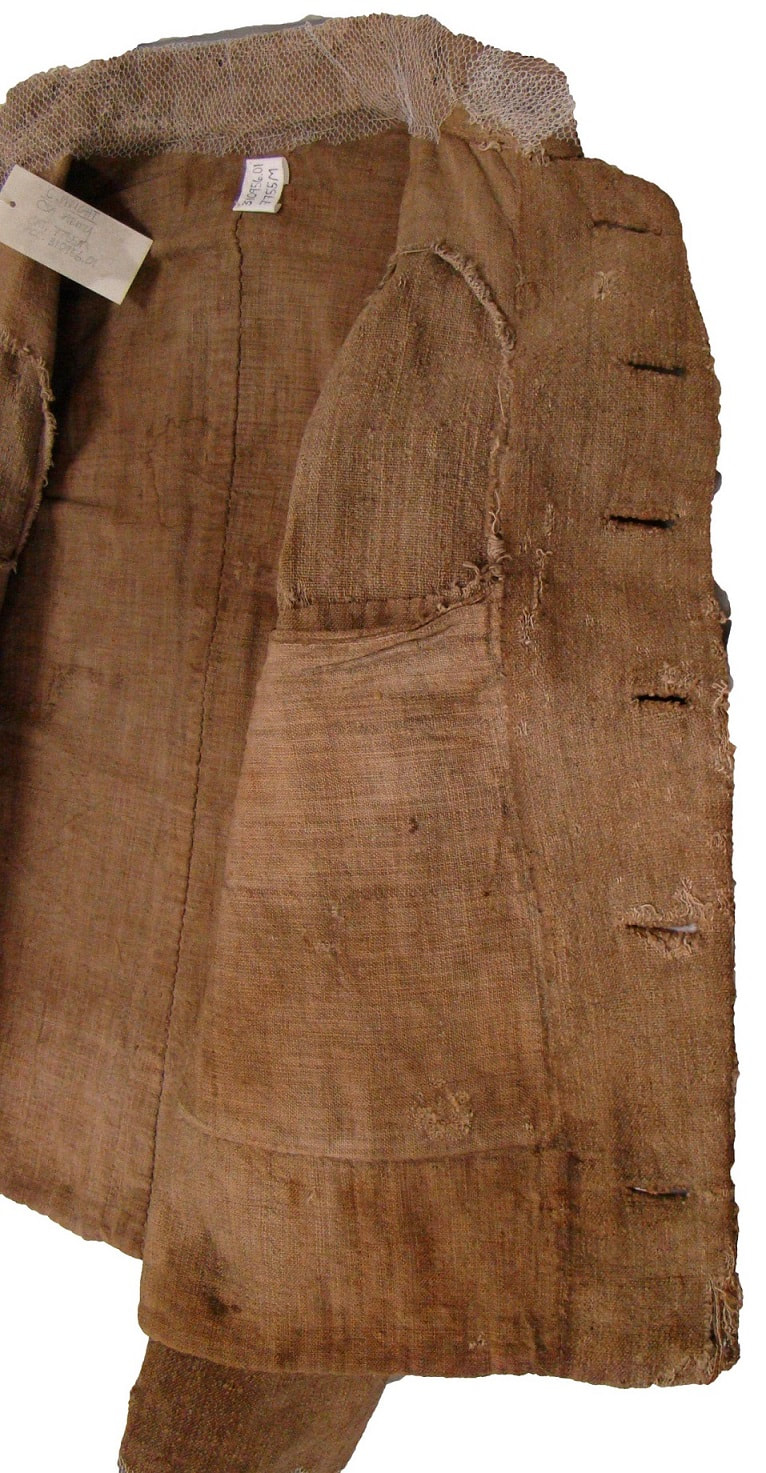

Nashville was the hub of the Tennessee State quartermaster department that switched to a Confederate operation in the summer of 1861. As of May 9, 1861, Vernon K. Stevenson was the Tennessee State Quartermaster General, with George Cunningham in charge of the Nashville Depot and Thomas Peters heading the Memphis Depot. Stevenson also established a quartermaster depot in Knoxville.[3] The Nashville Depot relied on contracts with local tailors and sewing machine companies to make the ready-made clothing that it furnished to Confederate troops.[4] The Tennessee State Penitentiary at Nashville, under the supervision of W.R. Hunt, also produced clothing for the depot, to include wool hats, army shoes, and Negro brogans.[5] Lastly, Stevenson relied heavily upon donations from volunteer aid societies and prosperous donors. The quartermaster made appeals for clothing and fabrics from the local citizens in August and September 1861. The Nashville quartermaster offered premium prices for “heavy grey jeans and thick white linsey.”[6] Stevenson and others also made appeals at the same time for clothing: heavy brown or gray jeans pants and roundabouts, army jackets (or pea jackets), both lined throughout and with side and vest pockets. The jackets were to extend four inches past the pants’ waistband and be made large enough to fit over a vest or shirt. “Grey goods” were preferred for the coat or jacket, but any kind of woolen goods were acceptable. The quartermaster also asked for woolen socks, gloves and drawers; flannel shirts and over shirts; heavy vests made of jeans, linsey or kersey; overcoats, or loose sack or hunting shirts with a belt; blankets or yarn coverlids; heavy shoes or boots; and, felt or wool hats.[7] Prosperous citizens also made significant donations of clothing, fabrics and equipment, as well. For instance, Douglas & Company donated a quantity of army blankets, tweeds, satinettes, flannels and clothing in 1861.[8] Photos LC 33315 & 37155 frocks

Soon after the war began, the thoughtful leadership of the South realized that the government needed to supply its armies with clothing. The individual soldiers, their families, and even philanthropic organizations could not do this alone. None had the resources equal to this task except for the government. Two systems were adopted to cope with this need: a government depot system and a system of reimbursement, called commutation. Both systems functioned alongside each other, but the reimbursement system that required either individuals or organizations to supply soldier’s clothing proved ineffective. The Confederate congress abolished the commutation system on October 8, 1862; thereby, making the Confederate quartermaster department solely responsible for clothing Confederate troops. By that time, the quartermaster depots were fully operational, so this posed no problem. In fact, the commutation system was wrought with inefficiency and fostered unhealthy speculation for scarce resources: resources that needed to be managed and properly distributed.[1] It also wasted intangible resources such as time and energy on a procurement process where government agents were routinely underbid. Finally, the clothing industry that grew out of this system victimized workers with low wages in rapidly inflating currency. This exploitation hampered both morale and support for the war effort. Had the war lasted but a year or two, the commutation system might have been the lesser evil to establishing an expensive government production apparatus. In any case, within a few months the war’s outbreak, Southern leadership began contracting for clothing to adequately supply its armies with clothing, especially for the impending winter months.

Early efforts to provide clothing drew on the resources of the Confederate quartermaster, state governments, small factories and volunteer aid societies. Special attention was given to fostering the establishment of manufacturing facilities, and the Western Confederacy had had several operations that provided a good start in this regard. Indeed, there was already a burgeoning textile industry there by the start of the war. This consisted of numerous small, privately-owned factories or mills in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi, that produced cotton and woolen yarns, and fabrics. These small factories provided cloth or finished clothing for the military once the war began, and they formed the backbone of the Confederacy’s clothing industry in the Lower South early in the war. This was especially the case when the large industrial centers at Nashville, Tennessee, and New Orleans, Louisiana fell to the enemy within the first year of the war. Additionally, nearly every state in the region had a state-operated penitentiary mill that fabricated cloth. These combined resources offered a source of clothing materials that the Confederate quartermaster could draw upon.

The first operation to consider would be the region’s chief manufacturing centers of New Orleans and Nashville. These cities provide insights into the Lower South’s capabilities and intent for the efficient manufacture of clothing. Regrettably, both places fell to enemy forces relatively early in the war, and quartermasters had to re-establish these operations elsewhere, beginning on a smaller scale.[2] Nashville, which is technically in the Upper South, figures largely into this study because its operation supplied troops from the Lower South, and when the city was captured, its operations were all shifted to the Lower South in Georgia and Mississippi.

Nashville was the hub of the Tennessee State quartermaster department that switched to a Confederate operation in the summer of 1861. As of May 9, 1861, Vernon K. Stevenson was the Tennessee State Quartermaster General, with George Cunningham in charge of the Nashville Depot and Thomas Peters heading the Memphis Depot. Stevenson also established a quartermaster depot in Knoxville.[3] The Nashville Depot relied on contracts with local tailors and sewing machine companies to make the ready-made clothing that it furnished to Confederate troops.[4] The Tennessee State Penitentiary at Nashville, under the supervision of W.R. Hunt, also produced clothing for the depot, to include wool hats, army shoes, and Negro brogans.[5] Lastly, Stevenson relied heavily upon donations from volunteer aid societies and prosperous donors. The quartermaster made appeals for clothing and fabrics from the local citizens in August and September 1861. The Nashville quartermaster offered premium prices for “heavy grey jeans and thick white linsey.”[6] Stevenson and others also made appeals at the same time for clothing: heavy brown or gray jeans pants and roundabouts, army jackets (or pea jackets), both lined throughout and with side and vest pockets. The jackets were to extend four inches past the pants’ waistband and be made large enough to fit over a vest or shirt. “Grey goods” were preferred for the coat or jacket, but any kind of woolen goods were acceptable. The quartermaster also asked for woolen socks, gloves and drawers; flannel shirts and over shirts; heavy vests made of jeans, linsey or kersey; overcoats, or loose sack or hunting shirts with a belt; blankets or yarn coverlids; heavy shoes or boots; and, felt or wool hats.[7] Prosperous citizens also made significant donations of clothing, fabrics and equipment, as well. For instance, Douglas & Company donated a quantity of army blankets, tweeds, satinettes, flannels and clothing in 1861.[8] Photos LC 33315 & 37155 frocks

The quartermaster operation in Tennessee drew upon local sources for fabrics, but went further afield, as well. Agent R.C. McNairy purchased jeans cloth from Louisville, Kentucky amounting to 30,000 yards of gray satinet, 25,000 yards of plain red flannel and 25,000 yards of red, gray and blue flannel.[9] Another agent, Irby Morgan purchased wool from Texas, and a small quantity of fabric from the Texas State Penitentiary mill at Huntsville. East Texas was one of the South’s largest wool-producing areas.[10] Morgan bought 450,000 pounds of wool from Texas from 1861 to about April 1862. He initially sent the Texas wool to Nashville to be spun and woven, but when Nashville was threatened, he had the wool delivered to other mills across the South. From this wool, Morgan procured 500,000 yards of gray cloth.[11] Likewise, Morgan had the Huntsville cloth at first sent to Nashville, but when the city fell, he had the last consignment of cloth sent to New Orleans. Not including shipments in November 1861, the Huntsville mill sent Morgan 11,300 yards of woolen cloth, 25,300 yards of cotton jeans, and approximately 140,000 yards of osnaburgs between December 1, 1861 and May 1, 1862.[12]

The Tennessee quartermaster department began operations on May 29, 1861 by hiring tailors, and two weeks later issued the first clothing (gray uniforms) to the troops.[13] By September 1861, the Nashville Depot was making 2,000 garments per day, and had 14,000 suits of clothing, 12,000 pairs of shoes, and 12,000 “6-4” wool blankets on hand.[14] By that autumn, the Tennessee depots were issuing uniforms to soldiers mustering into service, and supplying Confederate soldiers in Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas and Missouri.[15] The operation was consolidated somewhat by reducing the scale of operations in Memphis and Knoxville, and centralizing most of it in Nashville to facilitate manufacturing and distribution.[16] The depots appear to have made uniforms of gray or brown jeans that utilized a jacket (called a roundabout, pea jacket or army jacket).[17] The jeans color was described by Samuel R. Anderson’s Brigade, November 20, 1861, as follows, “Although we do not make a very uniform appearance, some having light and gray, and others dark-colored clothing.”[18] While the Nashville Depot was able to supply most of the department’s troops with clothing, supply could not keep up with the demand.[19] To the end of Nashville’s operations, the state and Confederate quartermasters relied on contributions from local aid societies to make up shortfalls in production. The depot closed when the city was evacuated on February 23, 1862. Most of the remaining clothing was distributed to the citizenry, the quartermaster only sending 700 bales of clothing southwards. George W. Cunningham, who had run the Nashville Depot, went south to Atlanta and established a clothing depot there. Memphis fell soon thereafter, on June 6, 1862. Nonetheless, while in operation the Tennessee quartermaster operation proved exceptionally successful. By October 1861, Stevenson and Cunningham announced, “We are now issuing six hundred suits a day & will be receiving that many in a few days & will go up we hope to a thousand suits a day soon.” In January 1862, the Tennessee depot obtained 153,168 yards of woolens, enough for 25,000 uniforms, and 163,110 yards of cotton goods for shirts. Tennessee’s February issues were comparable. By contrast, the quartermaster in northern Virginia, during the six-month period between October 11, 1861 and March 29, 1862, had issued only 26,214 pairs of shoes; 27,747 blankets; 14,604 uniforms, and 11,475 overcoats. The Tennessee clothing bureau had a monthly production of 25,000 to 30,000 uniforms per month throughout this same period, and its shoe and blanket production probably exceeded Richmond’s, as well, judging from the stocks on hand in September 1861. During its short tenure, the Nashville Depot issued more in any given month than Richmond, Virginia had in six.[20]

Few surviving uniforms can be documented to the Tennessee quartermaster operation, but numerous descriptions survive about the clothing that Confederates wore from the areas supplied by it. On August 30, 1861, the Tennessee quartermaster appealed to the citizenry clothing in the Clarksville Chronicle [Tennessee], calling for brown jeans pants, linsey shirts and drawers, and for gray coats or jackets, if possible.[21] A New York Herald correspondent described General Leonidas Polk’s troops in Columbus, Kentucky on October 30, 1861 as “rough, ill-clad, and ununiformed,” with only about half uniformed, while the balance had an “Army cap, coat, pants with a stripe” or “simply some ordinary [civilian] costume.”[22] At the Battle of Belmont, November 7, 1861, a private of 7th Iowa described Confederate enlisted clothing as, “…nearly all brownish-gray homespun.”[23]

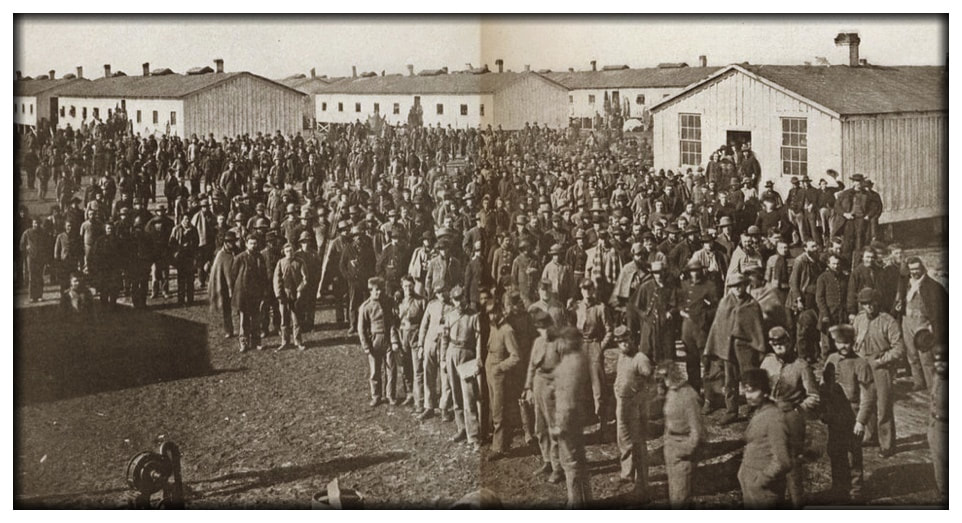

The Confederates at Fort Donelson were also supplied with clothing from the Tennessee depots. The Chicago Tribune described Confederates of the 7th Texas, 20th Mississippi and 49th Tennessee Infantry Regiments from that post on February 12, 1862 as follows, “The uniforms of the prisoners were just no uniforms at all, lacking all the characteristics of infantry, cavalry, or artillery costume, it being wholly un-uniform in color, cut, fashion, and manufacture. Some have coats of a butternut color cut in regular saque style, and others fashioned like those of our soldiers as jackets or frocks. Their pants are as diversified in color.”[24] The Bloomington Pantagraph [Illinois] made similar remarks on February 21 and 25, 1862, noting, “…such a thing as uniformity in dress was impossible to find, as there were no two dressed alike. Butternut colored breeches with a broad black stripe down the sides seemed to be the favorite running gear for the legs, …,” and that they wore “…pants of every hue of butternut brown.”[25] On March 8, 1862, the Ottawa Free Trader [Illinois] wrote, “The said [Confederate] uniforms of all shades of colors, gray, brindle, and butternut, the last predominating. Hats and caps of all shades, forms, and quality, and boots and shoes ditto.”[26] The Carlyle Weekly Reveille [Illinois] echoed previous observations on February 23, 1862 with, “In the way of clothing… it was evident that no attempt was paid to uniformity. Coats, pants, and vests, were found of every known material, walnut bark dyed jeans greatly predominated. Most of the pants were ornamented by a broad black stripe down the outer seam, sometimes of velvet, but mostly of cloth or serge. Shirts and drawers are all of home manufacture, and of the coarsest description. I have a package of a half-dozen shirts made of fabric many degrees coarser than canvas duck. Of these they had plenty. Hats and caps were diversified, yet they had a uniform cap – gray with a black band.”[27] A final observation on Confederate uniforms at Fort Donelson stated, “…brown predominated, but [some] were clad in gray – all shades, sheep, iron, blue, and dirty gray. Most Confederates were in citizen clothes, their own military insignia being black stripes on their pants.”[28] These reports confirm a diversity in the patterns of uniforms issued by the Tennessee depots, but uniforms nonetheless. The quartermaster department in Tennessee officially prescribed jackets, but some firms and volunteer groups made frock coats instead, as numerous photos attest. The frocks varied in button counts, color shading and facings, but were usually made of coarse jeans. Doubtless, Northerners were biased in considering any “butternut jeans” clothing as homespun or citizen clothes, whether cut as uniform or issued by a depot. Apparently, the depots managed a small measure of uniformity by issuing gray caps with black bands and putting black stripes on the pants.

The Tennessee quartermaster department began operations on May 29, 1861 by hiring tailors, and two weeks later issued the first clothing (gray uniforms) to the troops.[13] By September 1861, the Nashville Depot was making 2,000 garments per day, and had 14,000 suits of clothing, 12,000 pairs of shoes, and 12,000 “6-4” wool blankets on hand.[14] By that autumn, the Tennessee depots were issuing uniforms to soldiers mustering into service, and supplying Confederate soldiers in Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas and Missouri.[15] The operation was consolidated somewhat by reducing the scale of operations in Memphis and Knoxville, and centralizing most of it in Nashville to facilitate manufacturing and distribution.[16] The depots appear to have made uniforms of gray or brown jeans that utilized a jacket (called a roundabout, pea jacket or army jacket).[17] The jeans color was described by Samuel R. Anderson’s Brigade, November 20, 1861, as follows, “Although we do not make a very uniform appearance, some having light and gray, and others dark-colored clothing.”[18] While the Nashville Depot was able to supply most of the department’s troops with clothing, supply could not keep up with the demand.[19] To the end of Nashville’s operations, the state and Confederate quartermasters relied on contributions from local aid societies to make up shortfalls in production. The depot closed when the city was evacuated on February 23, 1862. Most of the remaining clothing was distributed to the citizenry, the quartermaster only sending 700 bales of clothing southwards. George W. Cunningham, who had run the Nashville Depot, went south to Atlanta and established a clothing depot there. Memphis fell soon thereafter, on June 6, 1862. Nonetheless, while in operation the Tennessee quartermaster operation proved exceptionally successful. By October 1861, Stevenson and Cunningham announced, “We are now issuing six hundred suits a day & will be receiving that many in a few days & will go up we hope to a thousand suits a day soon.” In January 1862, the Tennessee depot obtained 153,168 yards of woolens, enough for 25,000 uniforms, and 163,110 yards of cotton goods for shirts. Tennessee’s February issues were comparable. By contrast, the quartermaster in northern Virginia, during the six-month period between October 11, 1861 and March 29, 1862, had issued only 26,214 pairs of shoes; 27,747 blankets; 14,604 uniforms, and 11,475 overcoats. The Tennessee clothing bureau had a monthly production of 25,000 to 30,000 uniforms per month throughout this same period, and its shoe and blanket production probably exceeded Richmond’s, as well, judging from the stocks on hand in September 1861. During its short tenure, the Nashville Depot issued more in any given month than Richmond, Virginia had in six.[20]

Few surviving uniforms can be documented to the Tennessee quartermaster operation, but numerous descriptions survive about the clothing that Confederates wore from the areas supplied by it. On August 30, 1861, the Tennessee quartermaster appealed to the citizenry clothing in the Clarksville Chronicle [Tennessee], calling for brown jeans pants, linsey shirts and drawers, and for gray coats or jackets, if possible.[21] A New York Herald correspondent described General Leonidas Polk’s troops in Columbus, Kentucky on October 30, 1861 as “rough, ill-clad, and ununiformed,” with only about half uniformed, while the balance had an “Army cap, coat, pants with a stripe” or “simply some ordinary [civilian] costume.”[22] At the Battle of Belmont, November 7, 1861, a private of 7th Iowa described Confederate enlisted clothing as, “…nearly all brownish-gray homespun.”[23]

The Confederates at Fort Donelson were also supplied with clothing from the Tennessee depots. The Chicago Tribune described Confederates of the 7th Texas, 20th Mississippi and 49th Tennessee Infantry Regiments from that post on February 12, 1862 as follows, “The uniforms of the prisoners were just no uniforms at all, lacking all the characteristics of infantry, cavalry, or artillery costume, it being wholly un-uniform in color, cut, fashion, and manufacture. Some have coats of a butternut color cut in regular saque style, and others fashioned like those of our soldiers as jackets or frocks. Their pants are as diversified in color.”[24] The Bloomington Pantagraph [Illinois] made similar remarks on February 21 and 25, 1862, noting, “…such a thing as uniformity in dress was impossible to find, as there were no two dressed alike. Butternut colored breeches with a broad black stripe down the sides seemed to be the favorite running gear for the legs, …,” and that they wore “…pants of every hue of butternut brown.”[25] On March 8, 1862, the Ottawa Free Trader [Illinois] wrote, “The said [Confederate] uniforms of all shades of colors, gray, brindle, and butternut, the last predominating. Hats and caps of all shades, forms, and quality, and boots and shoes ditto.”[26] The Carlyle Weekly Reveille [Illinois] echoed previous observations on February 23, 1862 with, “In the way of clothing… it was evident that no attempt was paid to uniformity. Coats, pants, and vests, were found of every known material, walnut bark dyed jeans greatly predominated. Most of the pants were ornamented by a broad black stripe down the outer seam, sometimes of velvet, but mostly of cloth or serge. Shirts and drawers are all of home manufacture, and of the coarsest description. I have a package of a half-dozen shirts made of fabric many degrees coarser than canvas duck. Of these they had plenty. Hats and caps were diversified, yet they had a uniform cap – gray with a black band.”[27] A final observation on Confederate uniforms at Fort Donelson stated, “…brown predominated, but [some] were clad in gray – all shades, sheep, iron, blue, and dirty gray. Most Confederates were in citizen clothes, their own military insignia being black stripes on their pants.”[28] These reports confirm a diversity in the patterns of uniforms issued by the Tennessee depots, but uniforms nonetheless. The quartermaster department in Tennessee officially prescribed jackets, but some firms and volunteer groups made frock coats instead, as numerous photos attest. The frocks varied in button counts, color shading and facings, but were usually made of coarse jeans. Doubtless, Northerners were biased in considering any “butternut jeans” clothing as homespun or citizen clothes, whether cut as uniform or issued by a depot. Apparently, the depots managed a small measure of uniformity by issuing gray caps with black bands and putting black stripes on the pants.

The Confederate uniforms worn at the Battles of Iuka and Corinth, Mississippi a half year later mirrored the descriptions from Fort Donelson and may represent the last stocks of clothing issued from the Nashville Depot. A member of the 29th Ohio Infantry described the General Sterling Price’s Confederate troops as uniformed in butternut with black trouser stripes.[29] After the Battle of Corinth, a soldier of the 95th Illinois Infantry remarked on December 15, 1862 of Confederate prisoners being marched North that, “Nearly eight hundred Rebel prisoners passed by late in the afternoon. They were nearly all clad in butternut suits with a gray cap. Their knapsacks were made of rawhide with the hair on the outside.”[30]

The South’s largest city, New Orleans, was likewise an industrial city, but on a greater scale than Nashville, already having an established textile and clothing industry by the outbreak of the war. William Watson, a soldier in the 3rd Louisiana Infantry, remarked that in May 1861 in New Orleans, “The constant rattle of steam-driven sewing machines from many buildings announced the extensive manufacture of saddlery equipments, tents, and army clothing…”[31] Extant records substantiate numerous clothing factories operating there and having supplied the Confederate quartermaster. The corroborating data of sales receipts for uniforms, shoes, hats and related military clothing span the period of January 1861 to March 1862: exactly the period beginning with Louisiana’s secession until New Orleans’s fall to Federal forces. While most of the city’s clothing factories undoubtedly made clothing and equipment for the Confederacy, only those with surviving sales receipts can be quantitatively assessed for what they provided. Close to New Orleans was the state capitol city of Baton Rouge. Baton Rouge housed the state’s penitentiary mill that had been established in 1832. The mill began the manufacture of heavy, plain weave cotton lowells, and coarse woolen cloth in 1838-39, producing 21,000 yards of lowells and 2,400 yards of wool cloth per week.[32] By the Civil War, the mill was making a, “…substantial material, known as jeans, being of a grayish-blue color,” or, “…a dark brown,” and was used to make Confederate uniforms.[33]

Perhaps the largest single New Orleans manufacturer of Confederate clothing was Hebrard & Co. In any case, their surviving records yield the largest quantities of clothing (bearing in mind that their records may be fragmentary and only give a sampling of the aggregate produced). With that caveat, Hebrard & Co. supplied between February and June 1861, 658 suits of “Artillery Uniform Coats and Pants,” 1,120 suits of “Infantry Uniform Coats and Pants,” and 343 unspecified suits of “Uniform Coats and Pants.” The suits were all priced at $7.75 each ($5.25 for the coat and $2.50 for the pants). Along with these suits, Hebrard furnished flannel shirts and cotton drawers in double quantities, ensuring that every suit came with two shirts and pairs of drawers. In August and September, Hebrard had apparently ceased supplying the branch-specific uniforms, switching to simpler clothing. During that time, he supplied 5,000 suits of “White Kentucky Jeans,” and 300 suits of “Gray Kentucky Jeans” (both at $5.50 per suit); and, 225 suits of “Gray Kersey” at $3.50 per suit. He also provided copious quantities of osnaburg shirts, exceeding the numbers of soldier suits.[34]

Another firm, Levy, Simon & Co., supplied clothing from July 1861 through the first quarter of 1862. Due to the smattering of surviving receipts, the quantities tell less than what the firm provided. Throughout the period, they sold shirts and blankets. During November and December, they sold overcoats, “Kersey Blouses and Pants,” (for $6.00 and $4.00 respectively), and “Uniform Jackets and Trousers,” (for $5.00 and $4.00 respectively). During the first quarter of 1862, they sold “Kersey Jackets and Trousers,” (for $6.50 and $4.50 respectively).[35] The French and American Clothing Store, M. Godchaux, Frere & Co., also provided “Kersey Jackets” in October 1861, and overcoats in March 1862.[36] Likewise, Joseph N. Robert & Co., provided “Kersey Coats and Pants” October.[37] N.C. Folger & Son provided 316 suits of “Infantry Uniform Coats and Pants,” and similar quantities of flannel shirts, cotton drawers and woolen socks. In October, Folger delivered to Arkansas “Attakapas Pantaloons,” “Super Cas Coats” and “Super Sat Coats,” (presumably, abbreviations for superior cassinet and satinet); “Pilot M Jackets” and “Kersey M Jackets:” and “Super Cas Pants.” Folger also delivered 243 overcoats to Richmond, Virginia.[38]

Several New Orleans firms supplied the Confederate quartermaster with headgear, as well, although the lack of receipts makes it impossible to determine their total contributions. At least the receipts give an idea of what was furnished. The firm of Belden & Eames for instance, provided between January and May 1861 “Infantry and Artillery Hats,” “Artillery Caps,” and “Black Wool Hats.”[39] During the same period, Bauer & Co., furnished “Glaze Caps” and “Fatigue Caps.”[40] In August, Frost & Co. sold “assorted hats and caps,” some of these being “black wool hats” or “black wool high crown hats.” They also furnished “Glazed Teamsters Hats” and “Cadet Zouave Hats.”[41] The last receipts date to March 1862, when the firm Fiquet & Boulet sold 199 caps to the quartermaster at $2.00 each.[42]

The city’s factories supplied the Confederate quartermaster with clothing until the Federals occupied the area. The records also bear out that manufacturers began by producing elaborate uniforms, judging by the differentiation of artillery and infantry uniforms. By the latter half of 1861, manufacturers had begun to simplify their products. In August, Hebrard was making undyed, natural white uniforms in response to a need for quickly-made, mass-produced clothing that was simple, practical and cheap. Other firms followed suit. Doubtless, the Confederate quartermaster was unwilling to pay for expensive, embellished, time-consuming soldier suits.

Perhaps the most renown story about the mass-produced, white, New Orleans-made uniforms comes from the 2nd Texas Infantry Regiment. The regiment’s commander, Colonel J.W. Moore, had sent a requisition for gray uniforms to the Confederate quartermaster at New Orleans prior to his regiment departing Houston, Texas on March 18, 1862. At the time, the 2nd Texas was dressed in captured, Federal blue uniforms, and Moore felt that the blue color would jeopardize his men in battle. When the regiment arrived in Corinth, Mississippi on April 1, 1862, the requisitioned Confederate uniforms were waiting for them. The packages of clothing, however, consisted of white wool jackets and trousers without any size designations. The white color surprised the Texans, and the absence of size markings caused a delay since the troops had to try on multiple garments to find a decent fit. Nevertheless, the distinctive color drew the Federals’ attention at the Battle of Shiloh a few days later, summed up in one Union prisoner’s comment that the 2nd Texas Regiment was “…them hell-cats that went into battle dressed in their grave clothes.”[43] The cloth used to make these uniforms was one of Irby Morgan’s last consignments of Huntsville goods, having been sent to New Orleans since Nashville had fallen. Morgan had promised to make the 2nd Texas Infantry Regiment’s uniforms from these woolens.[44] What is most significant about these white woolen uniforms is that they represent a trend in manufacturing. The Confederate factories in Mississippi would produce, and the Army of Mississippi would wear white woolen uniforms for much of the war. Additionally, the Texans’ uniform consignment was one of the last to leave New Orleans for the Confederate army, and it highlights how important the city was in supplying clothing to the Confederacy.

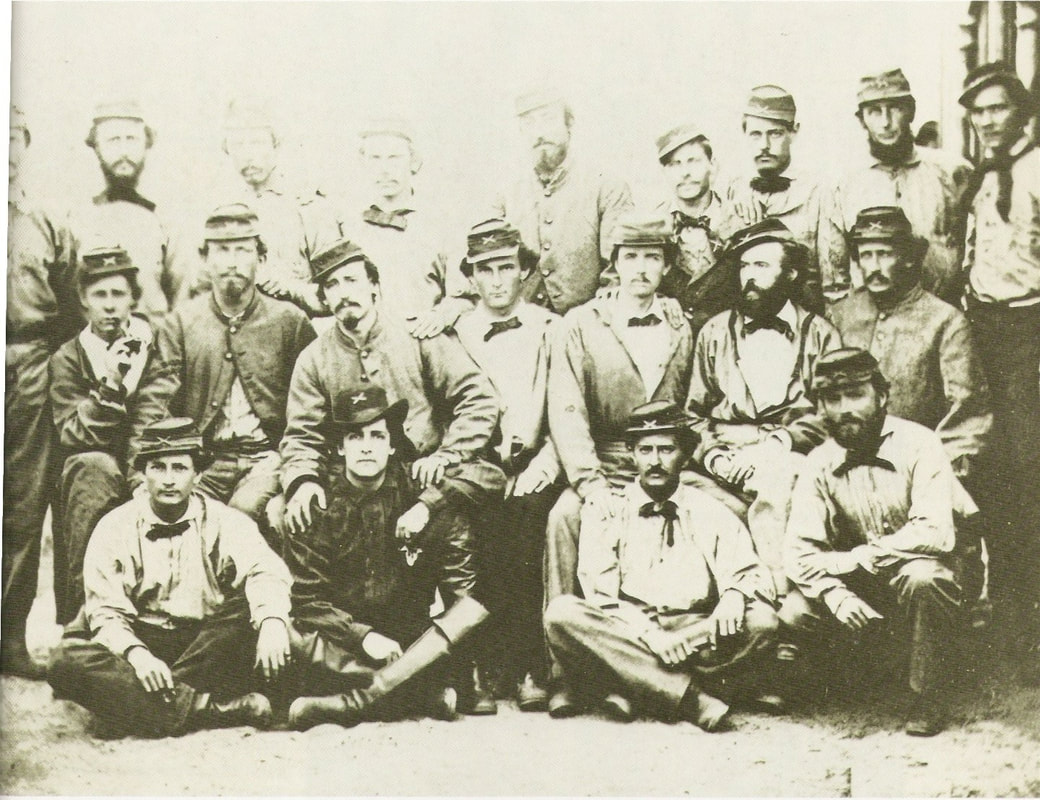

Turning now to the originals, one of the earliest surviving uniforms has provenance to Camp Moore, Louisiana, a Confederate training camp that operated from May 1861 to late 1862.[45] The surviving uniform matches a type observed in numerous photos from Camp Moore and other Louisiana training camps. The Camp Moore uniforms were probably manufactured in New Orleans, in which case prior to the city’s fall in April 1862. The Camp Moore uniform constitutes an identifiable type, but, there are slight variations between the surviving jacket and pair of trousers, and the uniforms observed in numerous images. These variations include such factors as differing numbers of front buttons; plumb collars; and, placement of the black tape. Nonetheless, the jackets share some general characteristics: most have nine front buttons; three-eighths inch black worsted tape that extends all around the entire edge of the jacket and the top edge of the collar; the cuffs are faced with tape that is chevron-shaped in front; there are shoulder straps likewise faced with tape; and, the front panels are matching (no plumb edge collar on the left side). Most of the jackets may have had belt loops faced with tape, but these are seldom visible in portraits. The jackets also feature brass, military buttons.

This style of jacket, conveniently dubbed the Camp Moore uniform, although it was issued at training camps throughout Louisiana, was also issued in a frock coat variation. Numerous photos attest to the prolific usage of the frock with similar trimmings. An original single-breasted frock coat of this type resides in the Don Troiani collection and is attributed to a soldier of the 5th Louisiana Infantry.[46] The Southern frock coat, based upon the US Army model 1851 uniform, was indeed the preferred enlisted tunic early in the war. However, its usage yielded to the needs of economy and practicality, and the simpler jacket quickly replaced it, with the quartermaster prescribing its use in May 1861.[47]

The South’s largest city, New Orleans, was likewise an industrial city, but on a greater scale than Nashville, already having an established textile and clothing industry by the outbreak of the war. William Watson, a soldier in the 3rd Louisiana Infantry, remarked that in May 1861 in New Orleans, “The constant rattle of steam-driven sewing machines from many buildings announced the extensive manufacture of saddlery equipments, tents, and army clothing…”[31] Extant records substantiate numerous clothing factories operating there and having supplied the Confederate quartermaster. The corroborating data of sales receipts for uniforms, shoes, hats and related military clothing span the period of January 1861 to March 1862: exactly the period beginning with Louisiana’s secession until New Orleans’s fall to Federal forces. While most of the city’s clothing factories undoubtedly made clothing and equipment for the Confederacy, only those with surviving sales receipts can be quantitatively assessed for what they provided. Close to New Orleans was the state capitol city of Baton Rouge. Baton Rouge housed the state’s penitentiary mill that had been established in 1832. The mill began the manufacture of heavy, plain weave cotton lowells, and coarse woolen cloth in 1838-39, producing 21,000 yards of lowells and 2,400 yards of wool cloth per week.[32] By the Civil War, the mill was making a, “…substantial material, known as jeans, being of a grayish-blue color,” or, “…a dark brown,” and was used to make Confederate uniforms.[33]

Perhaps the largest single New Orleans manufacturer of Confederate clothing was Hebrard & Co. In any case, their surviving records yield the largest quantities of clothing (bearing in mind that their records may be fragmentary and only give a sampling of the aggregate produced). With that caveat, Hebrard & Co. supplied between February and June 1861, 658 suits of “Artillery Uniform Coats and Pants,” 1,120 suits of “Infantry Uniform Coats and Pants,” and 343 unspecified suits of “Uniform Coats and Pants.” The suits were all priced at $7.75 each ($5.25 for the coat and $2.50 for the pants). Along with these suits, Hebrard furnished flannel shirts and cotton drawers in double quantities, ensuring that every suit came with two shirts and pairs of drawers. In August and September, Hebrard had apparently ceased supplying the branch-specific uniforms, switching to simpler clothing. During that time, he supplied 5,000 suits of “White Kentucky Jeans,” and 300 suits of “Gray Kentucky Jeans” (both at $5.50 per suit); and, 225 suits of “Gray Kersey” at $3.50 per suit. He also provided copious quantities of osnaburg shirts, exceeding the numbers of soldier suits.[34]

Another firm, Levy, Simon & Co., supplied clothing from July 1861 through the first quarter of 1862. Due to the smattering of surviving receipts, the quantities tell less than what the firm provided. Throughout the period, they sold shirts and blankets. During November and December, they sold overcoats, “Kersey Blouses and Pants,” (for $6.00 and $4.00 respectively), and “Uniform Jackets and Trousers,” (for $5.00 and $4.00 respectively). During the first quarter of 1862, they sold “Kersey Jackets and Trousers,” (for $6.50 and $4.50 respectively).[35] The French and American Clothing Store, M. Godchaux, Frere & Co., also provided “Kersey Jackets” in October 1861, and overcoats in March 1862.[36] Likewise, Joseph N. Robert & Co., provided “Kersey Coats and Pants” October.[37] N.C. Folger & Son provided 316 suits of “Infantry Uniform Coats and Pants,” and similar quantities of flannel shirts, cotton drawers and woolen socks. In October, Folger delivered to Arkansas “Attakapas Pantaloons,” “Super Cas Coats” and “Super Sat Coats,” (presumably, abbreviations for superior cassinet and satinet); “Pilot M Jackets” and “Kersey M Jackets:” and “Super Cas Pants.” Folger also delivered 243 overcoats to Richmond, Virginia.[38]

Several New Orleans firms supplied the Confederate quartermaster with headgear, as well, although the lack of receipts makes it impossible to determine their total contributions. At least the receipts give an idea of what was furnished. The firm of Belden & Eames for instance, provided between January and May 1861 “Infantry and Artillery Hats,” “Artillery Caps,” and “Black Wool Hats.”[39] During the same period, Bauer & Co., furnished “Glaze Caps” and “Fatigue Caps.”[40] In August, Frost & Co. sold “assorted hats and caps,” some of these being “black wool hats” or “black wool high crown hats.” They also furnished “Glazed Teamsters Hats” and “Cadet Zouave Hats.”[41] The last receipts date to March 1862, when the firm Fiquet & Boulet sold 199 caps to the quartermaster at $2.00 each.[42]

The city’s factories supplied the Confederate quartermaster with clothing until the Federals occupied the area. The records also bear out that manufacturers began by producing elaborate uniforms, judging by the differentiation of artillery and infantry uniforms. By the latter half of 1861, manufacturers had begun to simplify their products. In August, Hebrard was making undyed, natural white uniforms in response to a need for quickly-made, mass-produced clothing that was simple, practical and cheap. Other firms followed suit. Doubtless, the Confederate quartermaster was unwilling to pay for expensive, embellished, time-consuming soldier suits.

Perhaps the most renown story about the mass-produced, white, New Orleans-made uniforms comes from the 2nd Texas Infantry Regiment. The regiment’s commander, Colonel J.W. Moore, had sent a requisition for gray uniforms to the Confederate quartermaster at New Orleans prior to his regiment departing Houston, Texas on March 18, 1862. At the time, the 2nd Texas was dressed in captured, Federal blue uniforms, and Moore felt that the blue color would jeopardize his men in battle. When the regiment arrived in Corinth, Mississippi on April 1, 1862, the requisitioned Confederate uniforms were waiting for them. The packages of clothing, however, consisted of white wool jackets and trousers without any size designations. The white color surprised the Texans, and the absence of size markings caused a delay since the troops had to try on multiple garments to find a decent fit. Nevertheless, the distinctive color drew the Federals’ attention at the Battle of Shiloh a few days later, summed up in one Union prisoner’s comment that the 2nd Texas Regiment was “…them hell-cats that went into battle dressed in their grave clothes.”[43] The cloth used to make these uniforms was one of Irby Morgan’s last consignments of Huntsville goods, having been sent to New Orleans since Nashville had fallen. Morgan had promised to make the 2nd Texas Infantry Regiment’s uniforms from these woolens.[44] What is most significant about these white woolen uniforms is that they represent a trend in manufacturing. The Confederate factories in Mississippi would produce, and the Army of Mississippi would wear white woolen uniforms for much of the war. Additionally, the Texans’ uniform consignment was one of the last to leave New Orleans for the Confederate army, and it highlights how important the city was in supplying clothing to the Confederacy.

Turning now to the originals, one of the earliest surviving uniforms has provenance to Camp Moore, Louisiana, a Confederate training camp that operated from May 1861 to late 1862.[45] The surviving uniform matches a type observed in numerous photos from Camp Moore and other Louisiana training camps. The Camp Moore uniforms were probably manufactured in New Orleans, in which case prior to the city’s fall in April 1862. The Camp Moore uniform constitutes an identifiable type, but, there are slight variations between the surviving jacket and pair of trousers, and the uniforms observed in numerous images. These variations include such factors as differing numbers of front buttons; plumb collars; and, placement of the black tape. Nonetheless, the jackets share some general characteristics: most have nine front buttons; three-eighths inch black worsted tape that extends all around the entire edge of the jacket and the top edge of the collar; the cuffs are faced with tape that is chevron-shaped in front; there are shoulder straps likewise faced with tape; and, the front panels are matching (no plumb edge collar on the left side). Most of the jackets may have had belt loops faced with tape, but these are seldom visible in portraits. The jackets also feature brass, military buttons.

This style of jacket, conveniently dubbed the Camp Moore uniform, although it was issued at training camps throughout Louisiana, was also issued in a frock coat variation. Numerous photos attest to the prolific usage of the frock with similar trimmings. An original single-breasted frock coat of this type resides in the Don Troiani collection and is attributed to a soldier of the 5th Louisiana Infantry.[46] The Southern frock coat, based upon the US Army model 1851 uniform, was indeed the preferred enlisted tunic early in the war. However, its usage yielded to the needs of economy and practicality, and the simpler jacket quickly replaced it, with the quartermaster prescribing its use in May 1861.[47]

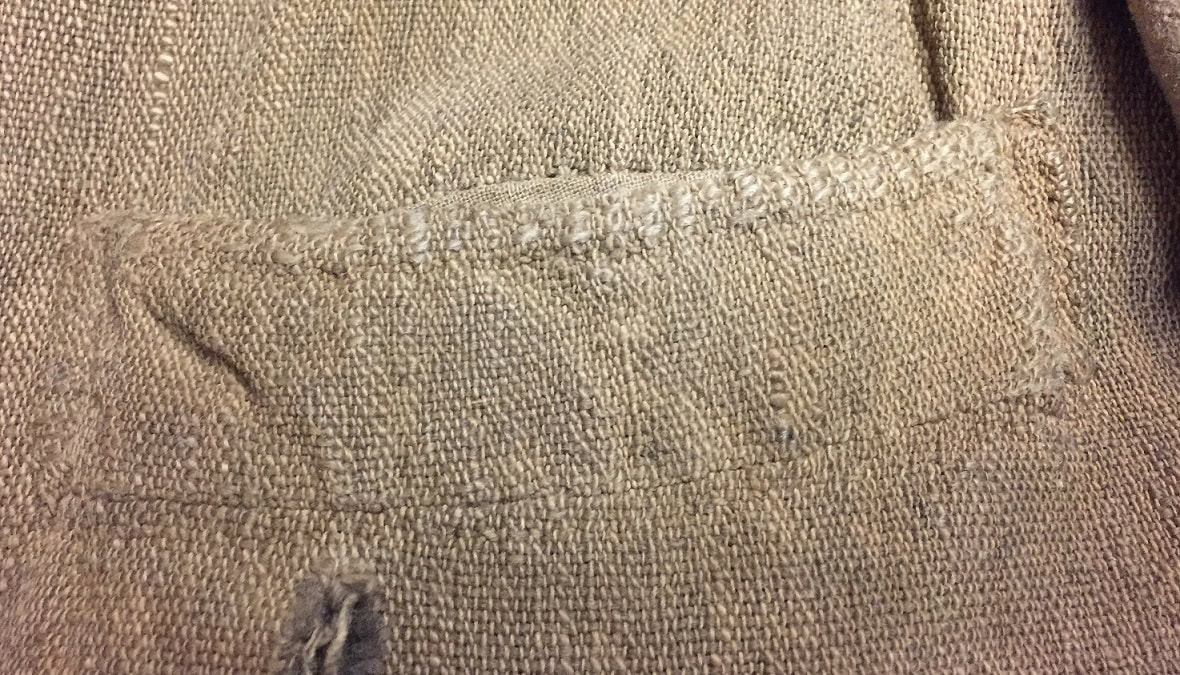

In any case, one original Camp Moore jacket survives as part of the Confederate Memorial Hall collection. This jacket was owned by Private Patrick O’Brien, Company H, 18th Louisiana Infantry. O’Brien enlisted at Camp Moore on November 19, 1861. After January 3, 1862, his regiment served in Mississippi and Alabama until October, at which time it moved to West Louisiana. There, O’Brien was captured and paroled twice, and lost an arm at his last battle, which effectively ended his active service. He presumably sent his Camp Moore jacket home for safe keeping sometime in 1862, since it is in relatively good condition. The jacket is made tan-colored, woolen-cotton satinet (faded from steel gray); has a plumb collar line on the buttonhole lapel; has shoulder straps and belt loops; and, nine front buttonholes. All the jacket’s buttons are now missing, but there were two buttons on each cuff, and buttons on the belt loops and shoulder straps. The black (now faded to olive green) worsted three-eighths inch tape extends all the way around the edge of the jacket and top of the collar; around the base of the cuffs, the rear cuff seam and comes to a point in front; around the outside edge of the shoulder straps; and, around the entire outline of the belt loops. Due to the extensive worsted tape, no topstitching is visible. The jacket has a six-piece body, two-piece sleeves and a one-piece-collar. The lining is made of a light weight, medium brown, cotton drill. The O’Brien jacket’s anomaly is its plumb collar, a feature not observed in several images studied.[48]

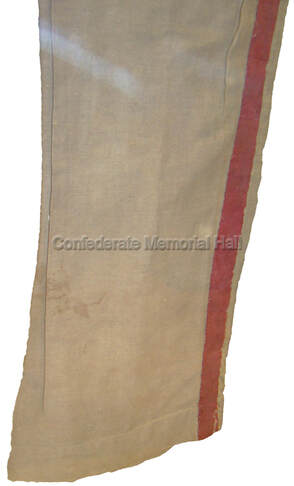

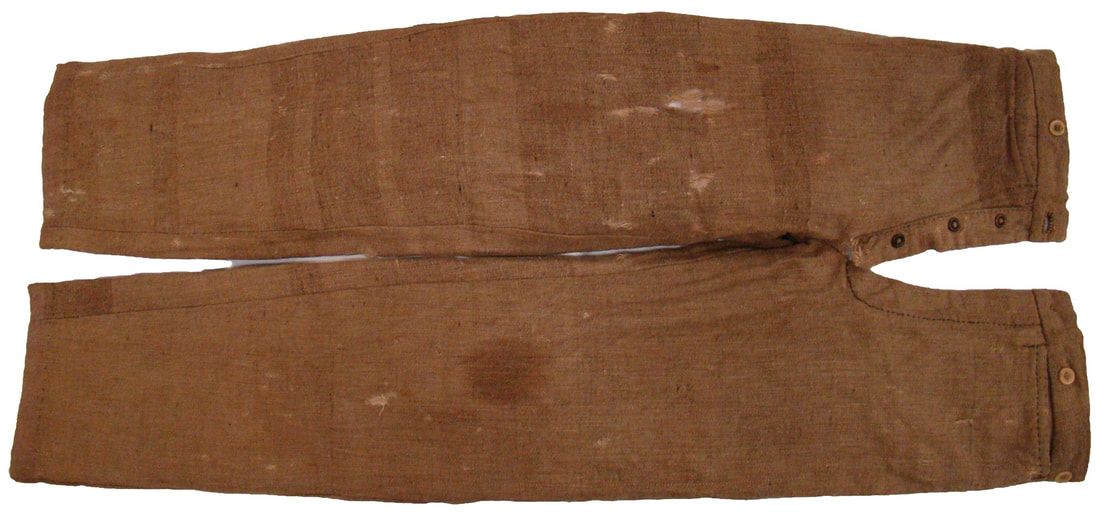

A surviving pair of pants worn by Private Enoch Pittman appears to be of the type that would have been issued with “Camp Moore” style jackets. In any case, Pittman’s pants have provenance to the time and place where the Camp Moore jackets were issued, and their pattern follows that observed in images of Camp Moore trousers. Pittman served in Company H, 1st Louisiana Heavy Artillery, and was at Camp Jackson when New Orleans fell in April 1862. Following the fall of the city, his command retreated to northern Mississippi, passing through Camp Moore on its way. Pittman fell sick in Mississippi and died in the hospital on January 29, 1863. He presumably received his trousers while stationed in New Orleans, and the pants were probably made by one of the manufacturers who supplied the troops at Camp Moore.[49]

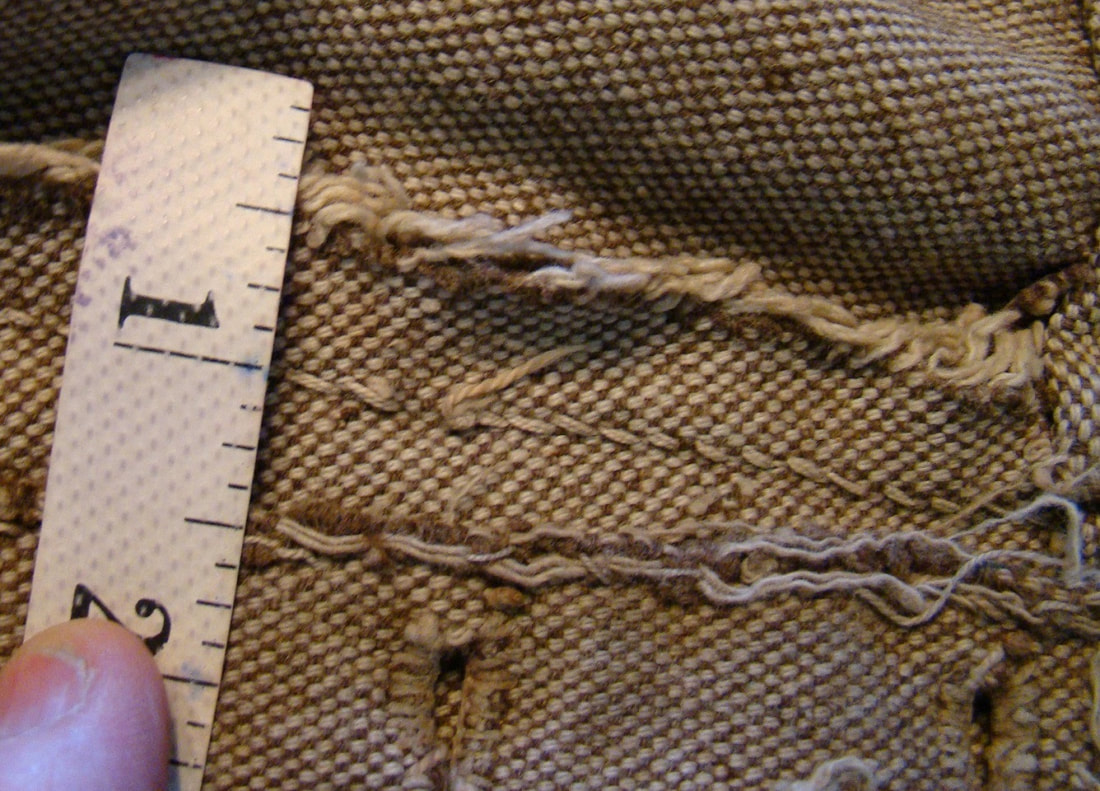

The pants are made of tan-colored, woolen-cotton jeans or cassinet. The original color has probably faded from steel gray. Some of the salient features include the integral waistband and the spring bottom cuffs. The flared cuffs were incorporated to accommodate a boot top since the pants were made for an artilleryman. The fly secured with five buttons (all now missing), has side seam pockets, and one-inch wide, red flannel stripes along the outer leg seams. The pants are lined with unbleached white, cotton drill (as far as was visible through the vitrine glass). The rear of the pants was not visible in the exhibit case, so it is not known whether the pants have an adjusting belt at the rear waist seam.

The pants are made of tan-colored, woolen-cotton jeans or cassinet. The original color has probably faded from steel gray. Some of the salient features include the integral waistband and the spring bottom cuffs. The flared cuffs were incorporated to accommodate a boot top since the pants were made for an artilleryman. The fly secured with five buttons (all now missing), has side seam pockets, and one-inch wide, red flannel stripes along the outer leg seams. The pants are lined with unbleached white, cotton drill (as far as was visible through the vitrine glass). The rear of the pants was not visible in the exhibit case, so it is not known whether the pants have an adjusting belt at the rear waist seam.

Finally, an example of the Camp Moore jacket without provenance survived as part of the Horse Soldier collection. The nine-button jacket has black wool tape along the top edge of the collar, the front, left lapel, the shoulder straps, and the cuffs (pointed). The sleeves have corporal chevrons made of the same black tape. The buttons are Louisiana pelican. The basic cloth is a light brownish gray jeans or satinet, and the lining is a natural white cotton.[50]

A newspaper description indicates that Pittman’s uniform may have been commonly worn by Louisiana artillerymen. The account states, “The Issaquena Artillery from Louisiana… are a really fine looking set of men. Their uniform, like all their Artillery, was of light gray with red trimmings, their caps having a wide red band.”[51] Likewise, a hand-tinted image of an Issaquena soldier, David E. Lusby, shows him wearing a nine-button, blue-gray jacket with a red collar and pointed cuffs, and matching blue-gray trousers.[52]

Surviving images provide the best insights to the Camp Moore uniform since they are so numerous and offer comparison of all the variances encountered from the usual features. Several of these images will be discussed using the features mentioned in the first paragraph describing the Camp Moore jacket as a basis. The subject’s variation from the usual characteristics will be highlighted in the portrait’s description. Unless otherwise stated, the pants cloth and color match that of the jacket, and have one-inch wide black stripes along the outside leg seams (where visible in the image).

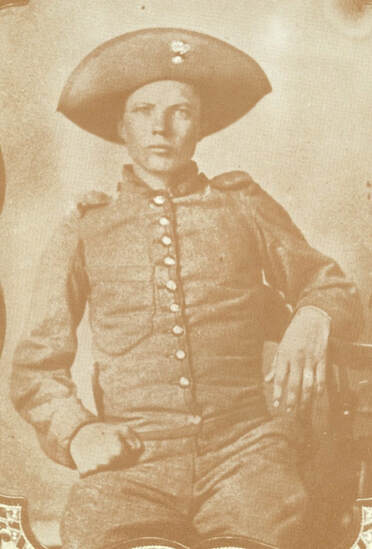

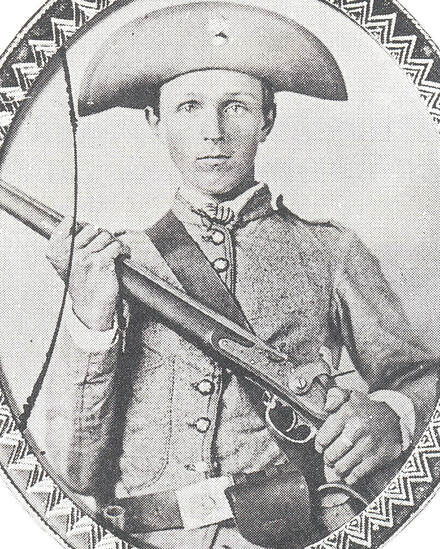

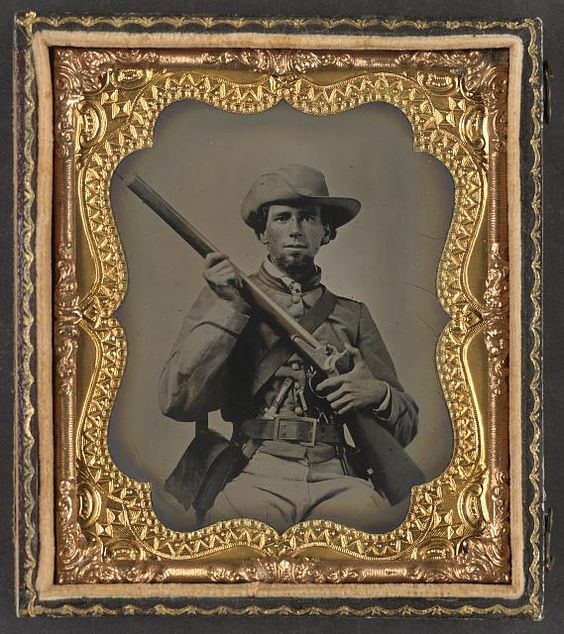

One of the most beloved Camp Moore portraits depicts a soldier with a hat, the front brim being pinned to the crown in front by an ordnance corps bomb badge. The unidentified soldier’s jacket varies from the usual features, however, in that it has ten buttons on the front and a large, exterior patch pocket on the left side. Remarkably, one of the belt loops is visible in the image.[53]

Another unidentified soldier’s image survives with the same type of bomb badge and slouch hat, and a similar jacket. While the jacket has the same exterior patch pocket on the left side, the jacket has only nine buttons on the front, indicating that the uniform is not a photographer’s prop, but an “issue” jacket.[54] In light of the two images depicting “bomb” badges, it is noteworthy that a hat worn at Vicksburg by Private A.L.H. Kernion, Company C, 23rd Louisiana Infantry, also has an ordnance bomb emblem painted on the front (described at length further on in this study). Perhaps this badge was made popular with Louisiana soldiers at Camp Moore and was unofficially adopted as a Louisiana emblem of sorts. Interestingly, Cincinnati artist Henry Mosler depicted this same bomb badge in a painting of a Confederate veteran in his 1868 painting, “The Lost Cause.”[55]

Surviving images provide the best insights to the Camp Moore uniform since they are so numerous and offer comparison of all the variances encountered from the usual features. Several of these images will be discussed using the features mentioned in the first paragraph describing the Camp Moore jacket as a basis. The subject’s variation from the usual characteristics will be highlighted in the portrait’s description. Unless otherwise stated, the pants cloth and color match that of the jacket, and have one-inch wide black stripes along the outside leg seams (where visible in the image).

One of the most beloved Camp Moore portraits depicts a soldier with a hat, the front brim being pinned to the crown in front by an ordnance corps bomb badge. The unidentified soldier’s jacket varies from the usual features, however, in that it has ten buttons on the front and a large, exterior patch pocket on the left side. Remarkably, one of the belt loops is visible in the image.[53]

Another unidentified soldier’s image survives with the same type of bomb badge and slouch hat, and a similar jacket. While the jacket has the same exterior patch pocket on the left side, the jacket has only nine buttons on the front, indicating that the uniform is not a photographer’s prop, but an “issue” jacket.[54] In light of the two images depicting “bomb” badges, it is noteworthy that a hat worn at Vicksburg by Private A.L.H. Kernion, Company C, 23rd Louisiana Infantry, also has an ordnance bomb emblem painted on the front (described at length further on in this study). Perhaps this badge was made popular with Louisiana soldiers at Camp Moore and was unofficially adopted as a Louisiana emblem of sorts. Interestingly, Cincinnati artist Henry Mosler depicted this same bomb badge in a painting of a Confederate veteran in his 1868 painting, “The Lost Cause.”[55]

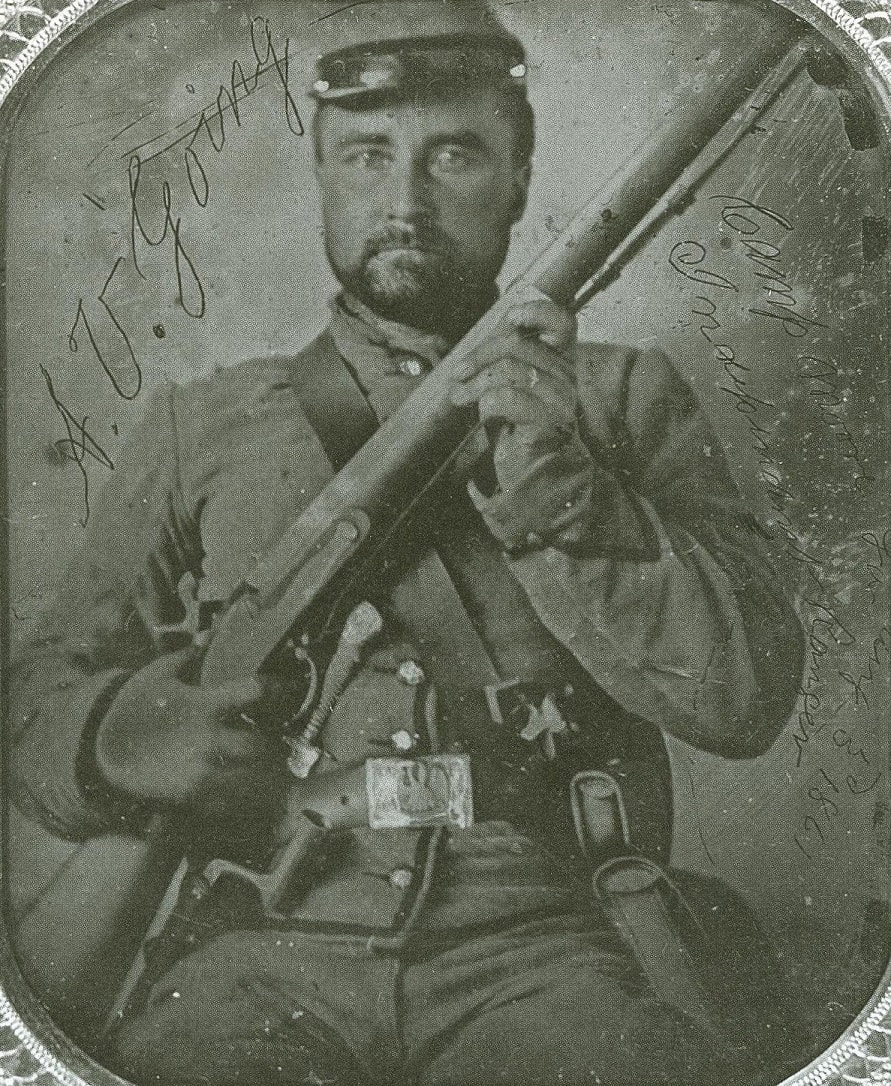

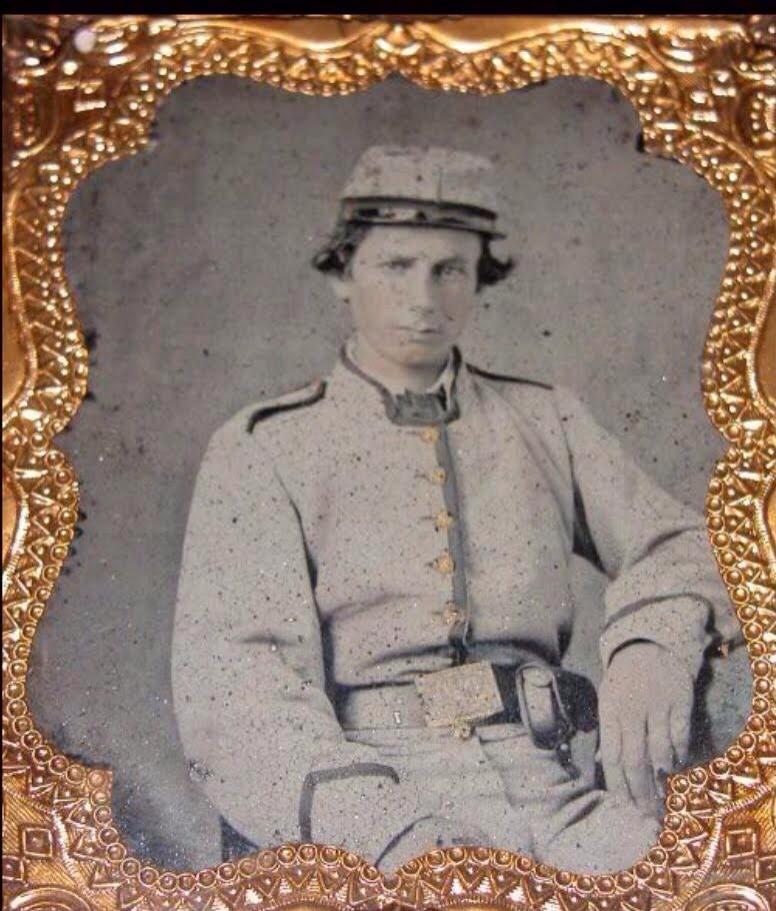

Four portraits depict soldiers with typical Camp Moore uniforms without the shoulder straps. Two of the soldiers are unidentified. Another, whose jacket is further simplified by having omitted the collar tape, is Daniel G. Lamberth, Company D, 3rd Louisiana Cavalry. Lamberth enlisted at St. Helena, May 19, 1862. This last mentioned, of Amasa V. Going, Company E, 12th Louisiana Infantry, is marked with the date it was made, August 18, 1861, making this Camp Moore style uniform the earliest documented of its type. Presumably, the manufacturer(s) made batches of the jackets without shoulder straps, just as they had made a batch with exterior patch pockets.[56]

Two full-length portraits of Company K, 10th Louisiana Infantrymen, Sergeant Joseph LeBleu and Private John Reeves, show them wearing nine-button jackets with shoulder straps, and matching pants. The jackets have tape only on the cuffs and top edge of the collar.[57]

An image of James Park Watson, Company H, 27th Louisiana Infantry, shows another atypical variant. While conforming to the general pattern in most regards, the front has only five or six buttons (difficult to count exactly due to the soldier’s posture and his accoutrements). Watson had enlisted at Camp Moore, April 22, 1862.[58]

Finally, while all Camp Moore jackets have core characteristics in common, a close study of the surviving portraits indicates that there are no quintessential examples that embody all core features. Every jacket observed has some slight variation. Private Michael Thomas Bryant, Company C, Gray's 28th Louisiana Infantry has a jacket that comes close to being typical in all respects, but the tape was omitted from the bottom edge. Bryant had enlisted at Monroe on May 10, 1862.[59] The closest to the core sample would be William H. Martin’s uniform, seen in the full-length portrait with his father. Even Martin’s jacket has one small variation: black tape has been attached along the base of the collar as well as along the top edge.[60] Nonetheless, the Camp Moore uniform constitutes an identifiable type. It is hardly surprising that the manufacture continually omitted features that simplified the jacket, considering that it was a rather elaborate jacket, and must have required much time and expense to make.

An image of James Park Watson, Company H, 27th Louisiana Infantry, shows another atypical variant. While conforming to the general pattern in most regards, the front has only five or six buttons (difficult to count exactly due to the soldier’s posture and his accoutrements). Watson had enlisted at Camp Moore, April 22, 1862.[58]

Finally, while all Camp Moore jackets have core characteristics in common, a close study of the surviving portraits indicates that there are no quintessential examples that embody all core features. Every jacket observed has some slight variation. Private Michael Thomas Bryant, Company C, Gray's 28th Louisiana Infantry has a jacket that comes close to being typical in all respects, but the tape was omitted from the bottom edge. Bryant had enlisted at Monroe on May 10, 1862.[59] The closest to the core sample would be William H. Martin’s uniform, seen in the full-length portrait with his father. Even Martin’s jacket has one small variation: black tape has been attached along the base of the collar as well as along the top edge.[60] Nonetheless, the Camp Moore uniform constitutes an identifiable type. It is hardly surprising that the manufacture continually omitted features that simplified the jacket, considering that it was a rather elaborate jacket, and must have required much time and expense to make.

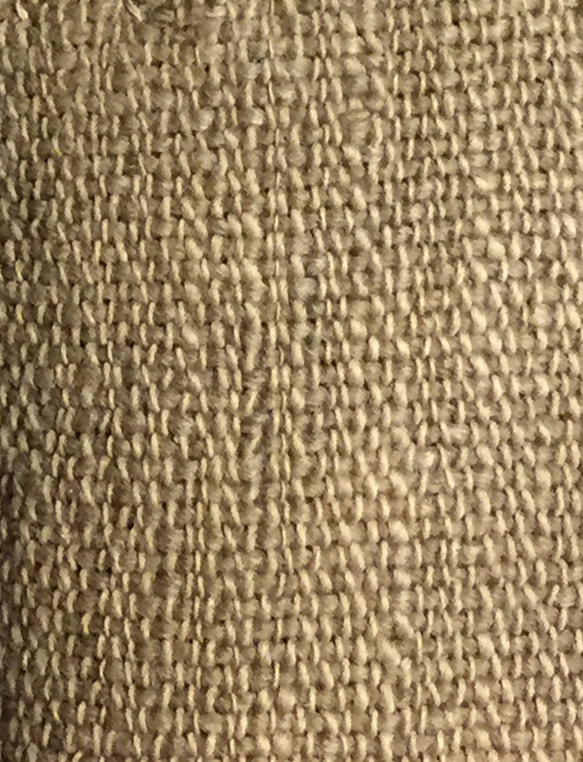

The next uniform type dating to the same timeframe as the Camp Moore uniform is the Seymour suit of jacket and trousers. Compared to the Camp Moore uniform, this is a simple, economical soldier suit entirely utilitarian and devoid of any martial embellishments. It is noteworthy, though, that the Seymour jacket’s high-quality, steel gray satinet, basic cloth is the same as that used to make the O’Brien jacket. This suggests that the cloth was from the same factory, and that the manufacturer opted to make a cheaper model of uniform.

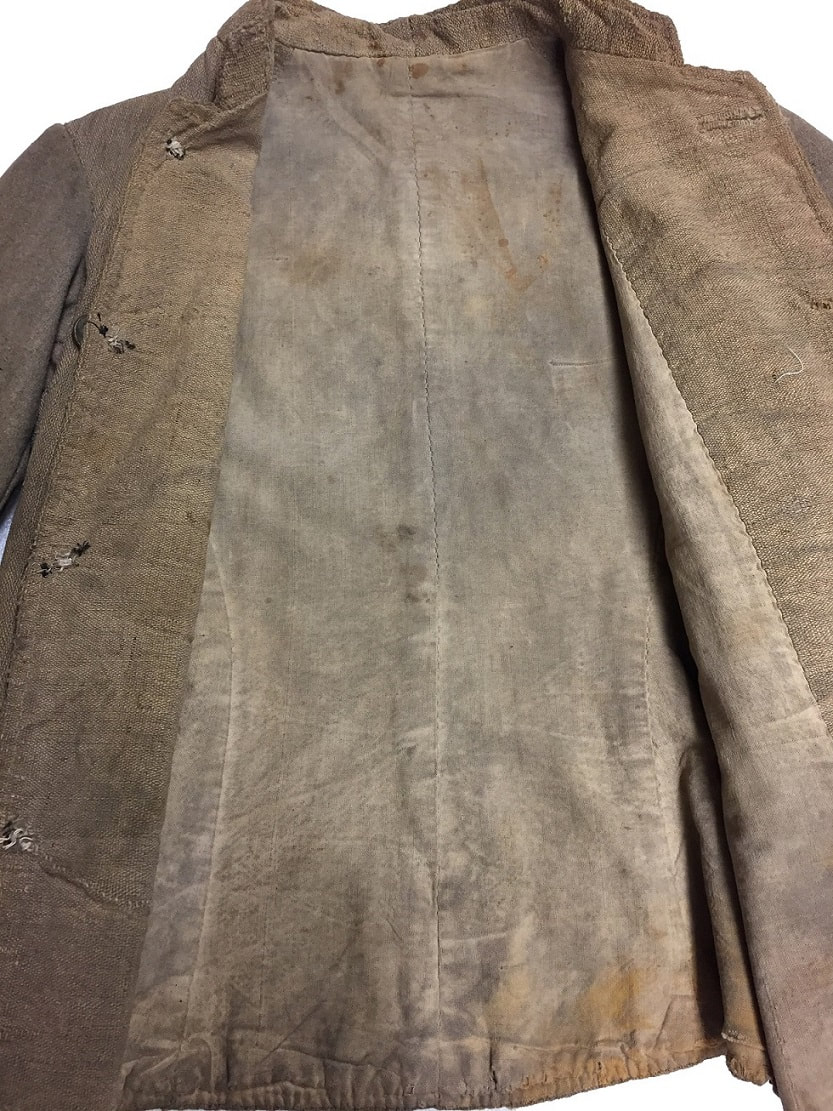

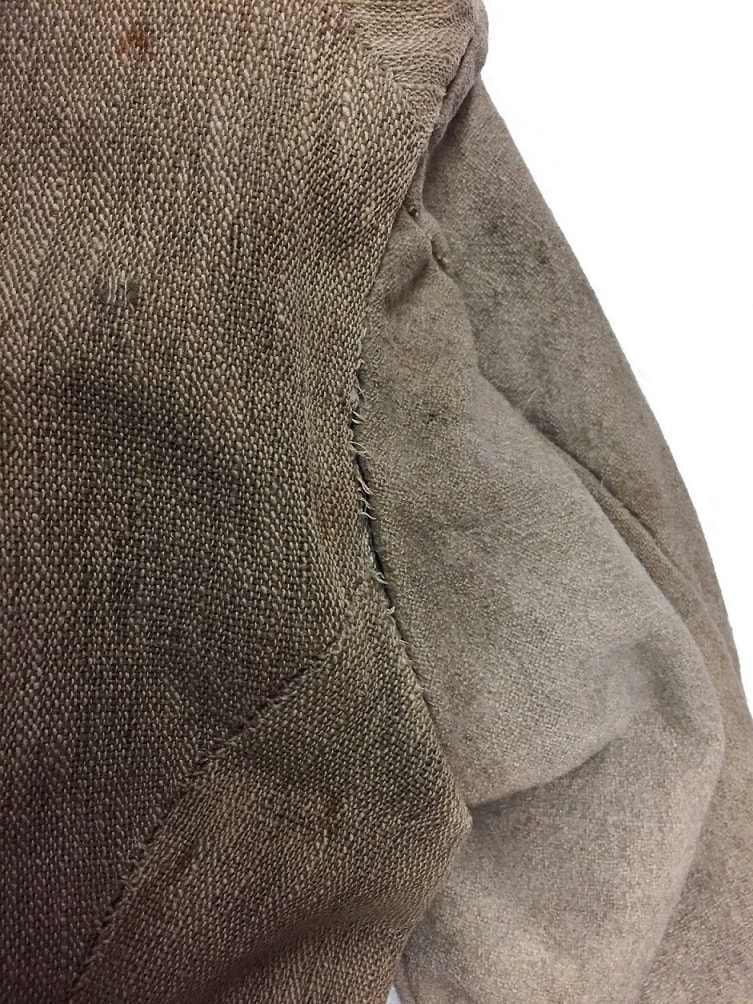

The jacket itself has five Louisiana pelican buttons, Tice LA223A1, on the front, three decorative Federal staff buttons on each cuff, and an exterior inset pocket on the left side.[61] It has a six-piece body, one-piece sleeves and a one-piece collar. The jacket is still a tannish-gray color, and probably faded from steel gray. The lining is unbleached osnaburg. The jacket has topstitching along the edges of the lapel facings from the collar to the bottom buttonhole (a sturdy backstitch); around the base of the collar (whipstitching that has come through the outside); and, around the cuffs (a backstitch about two inches above the cuff opening). The pants are made of a less expensive, coarsely woven plain, woolen-cotton fabric. The woolen weft is an oatmeal white color and the cotton warp a light tan color, which combines to give the pants an overall tan color from a few feet away. The pants are lined with unbleached osnaburg, the pockets have “V” openings, and the adjustment belt at the rear waistband seam has a rusty, non-japanned, iron swivel buckle on the left side. From a few yards away, the fabric of the jacket and pants look similar in texture and color.[62]

The museum records assert that the jacket was owned by Colonel Isaac G. Seymour, Commander of the 6th Louisiana Infantry. The 6th Louisiana organized at Camp Moore on June 4, 1861 and had moved to Virginia by July. Colonel Seymour may have acquired the enlisted soldier suit at Camp Moore, but it is also possible that his son, William, owned the uniform. This seems to be the case, because William is listed as “Colonel William Seymour,” and as the donor of a cadet gray, double-breasted officer frock coat with embroidered stars in the museum accession register. The accession register carries “Isaac Seymour” as the donor of the enlisted soldier suit. It seems that the registrar mixed up the names and donations. In any case, if the younger William Seymour owned the uniform, he probably drew it in East Louisiana. This is difficult to prove, however, since William’s service records are inconclusive.[63]

At least one image matches the cut of Seymour’s uniform: the simple untrimmed, five-button jacket and matching pants. It is a portrait of Private A.F. Aucoin, Company A, 9th Louisiana Infantry Battalion. Aucoin joined the army in early 1862, served first in central Mississippi, and then moved to Camp Moore, where his company organized into the 9th Louisiana on May 15, 1862. Aucoin may have received his uniform, weapon and accoutrements while at Camp Moore.[64]

Another image depicts a similar type of uniform, devoid of trim, but having shoulder straps and seven or eight flat “coin” buttons on the front. This is seen in the portrait of Reuben McMichael, Company G, 17th Louisiana Infantry. McMichael was stationed at both Camp Moore and Camp Benjamin during the winter of 1861-62, and presumably got his uniform at one of those two places before his ambrotype was taken on about February 7, 1862. He was subsequently killed during the Corinth Campaign, April-May 1862.[65] While not identical to the Seymour uniform, this early soldier suit represents the growing trend towards simplification of garments to ease the manufacturing process and save costs on time and materials.

The jacket itself has five Louisiana pelican buttons, Tice LA223A1, on the front, three decorative Federal staff buttons on each cuff, and an exterior inset pocket on the left side.[61] It has a six-piece body, one-piece sleeves and a one-piece collar. The jacket is still a tannish-gray color, and probably faded from steel gray. The lining is unbleached osnaburg. The jacket has topstitching along the edges of the lapel facings from the collar to the bottom buttonhole (a sturdy backstitch); around the base of the collar (whipstitching that has come through the outside); and, around the cuffs (a backstitch about two inches above the cuff opening). The pants are made of a less expensive, coarsely woven plain, woolen-cotton fabric. The woolen weft is an oatmeal white color and the cotton warp a light tan color, which combines to give the pants an overall tan color from a few feet away. The pants are lined with unbleached osnaburg, the pockets have “V” openings, and the adjustment belt at the rear waistband seam has a rusty, non-japanned, iron swivel buckle on the left side. From a few yards away, the fabric of the jacket and pants look similar in texture and color.[62]

The museum records assert that the jacket was owned by Colonel Isaac G. Seymour, Commander of the 6th Louisiana Infantry. The 6th Louisiana organized at Camp Moore on June 4, 1861 and had moved to Virginia by July. Colonel Seymour may have acquired the enlisted soldier suit at Camp Moore, but it is also possible that his son, William, owned the uniform. This seems to be the case, because William is listed as “Colonel William Seymour,” and as the donor of a cadet gray, double-breasted officer frock coat with embroidered stars in the museum accession register. The accession register carries “Isaac Seymour” as the donor of the enlisted soldier suit. It seems that the registrar mixed up the names and donations. In any case, if the younger William Seymour owned the uniform, he probably drew it in East Louisiana. This is difficult to prove, however, since William’s service records are inconclusive.[63]

At least one image matches the cut of Seymour’s uniform: the simple untrimmed, five-button jacket and matching pants. It is a portrait of Private A.F. Aucoin, Company A, 9th Louisiana Infantry Battalion. Aucoin joined the army in early 1862, served first in central Mississippi, and then moved to Camp Moore, where his company organized into the 9th Louisiana on May 15, 1862. Aucoin may have received his uniform, weapon and accoutrements while at Camp Moore.[64]

Another image depicts a similar type of uniform, devoid of trim, but having shoulder straps and seven or eight flat “coin” buttons on the front. This is seen in the portrait of Reuben McMichael, Company G, 17th Louisiana Infantry. McMichael was stationed at both Camp Moore and Camp Benjamin during the winter of 1861-62, and presumably got his uniform at one of those two places before his ambrotype was taken on about February 7, 1862. He was subsequently killed during the Corinth Campaign, April-May 1862.[65] While not identical to the Seymour uniform, this early soldier suit represents the growing trend towards simplification of garments to ease the manufacturing process and save costs on time and materials.

|

|

|

With the fall of New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Nashville and Memphis, two major industrial centers were permanently lost. The Lower South’s quartermaster operations would have to re-establish bases in places that were far less industrialized. Fortunately, by the summer of 1862, district quartermaster operations were in place throughout the South, and this served as an organizational basis for a new beginning. Furthermore, the last vestiges of commutation were on the way out, and the government operated quartermaster system was on the rise, despite numerous inefficiencies within the system for procurement, production and distribution of materials and supplies. Small factories served as the basis for the rising industrial base. Most were privately owned, but Alabama and Mississippi had their own penitentiary mills that furnished textiles at cost. The Jackson, Mississippi Penitentiary mill, which had been operating since 1849, made 1,000 yards of cloth per day.[66] The State of Alabama had a prison textile factory, too, built in the 1830s or -40s, but its production is not available.[67] In any case, as the Confederate government better organized and managed the country’s resources for the war effort, its own manufactories supplanted private ones. As the war continued, the government built ever larger manufacturing plants to fabricate clothing and equipage. However, it is with the story of the small factories of the Lower South that we must begin.

The industrial centers in Atlanta and Columbus, Georgia were the largest in the Lower South that remained under Confederate control by the summer of 1862. Their combined textile production, however, was not sufficient to supply all the armies of the Lower South. Nonetheless, Columbus was at times expected to supply troops outside of her district: namely Mississippi, Virginia, and even far away Arkansas. Given a dearth of large factories in the Lower South, it fell upon the numerous small textile mills to supply the armies with clothing. Their aggregate production furnished quartermasters with adequate quantities.

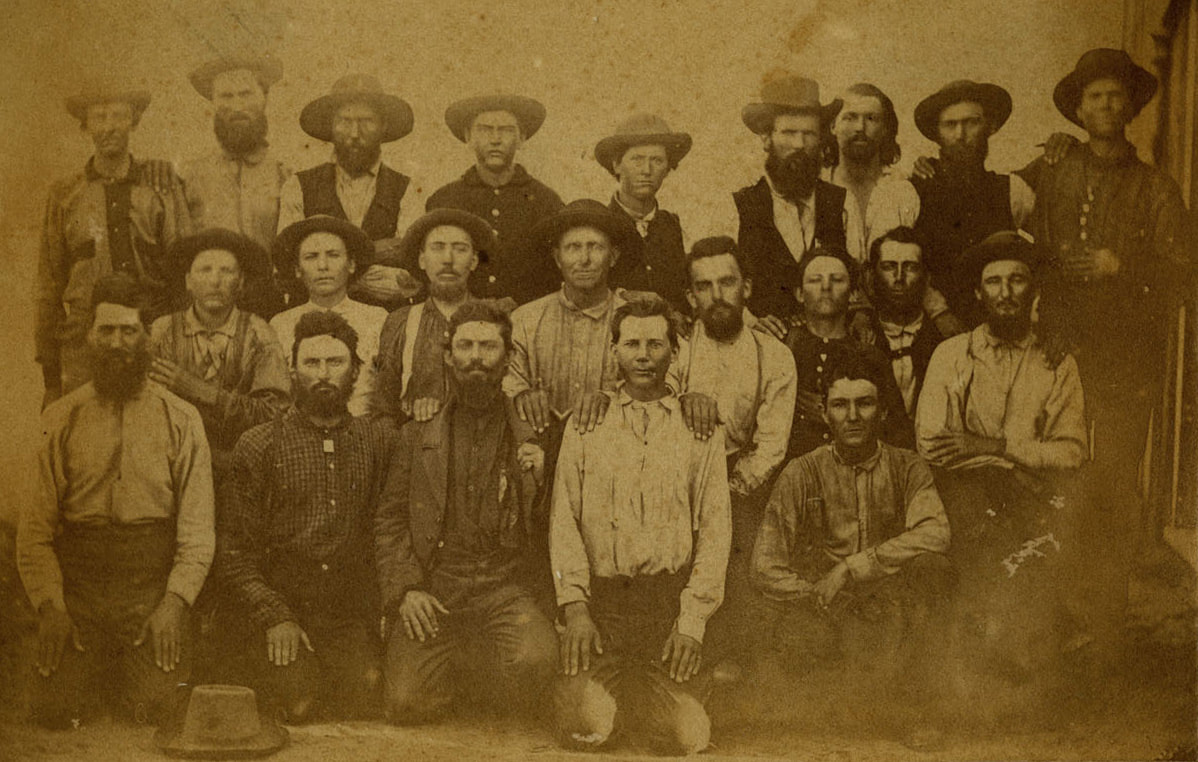

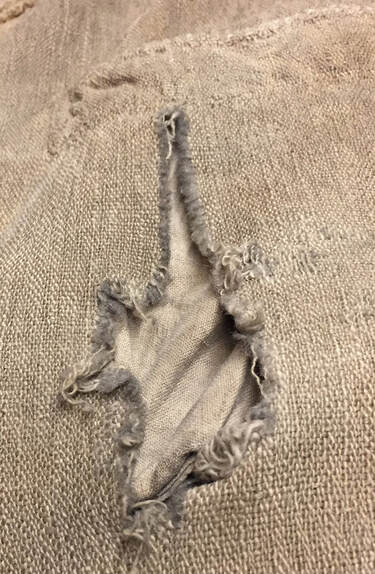

These small factories left their mark upon the character of Confederate depot uniforms in one peculiar way: there was a lack of uniformity within the patterns of jackets and trousers. Each small clothing factory used its own distinctive patterns, and its own particular cloth, linings and buttons, the latter contingent upon what it could obtain at any given time. The jackets, for instance, were uniform in only one respect: they were short, single-breasted, with standing collars. Other than that, there was tremendous latitude from factory to factory as to how the jackets were made. They differed in how many buttons were used to close the front of the jacket; some had colored trim facings and some did not; the placement of pockets differed widely; and, the subtle nuances of the cut are noticeable enough to determine that they were made at different places. Eventually, the government assumed more manufacturing responsibility, and production operations were consolidated and became larger. Along with the latter trend, the quartermaster general fostered uniformity in how clothing and equipment was made. But this level of systematic efficiency was not achieved until 1864, and so, the uniforms of the Lower South reflect the indifferent uniformity of numerous factories, each making its own variants of jackets and pants.

Some of the names of the Lower South’s clothing factories have survived, along with records of their production. Likewise, numerous jackets and pants survive that undoubtedly came from the small factories of the region. But since the factories did not mark their products, we may never know exactly what factory made a specific jacket or pair of pants. Additionally, due to the nature of procurement, collection and distribution, the possibility of pinpointing the exact origin of a surviving uniform is improbable.

For instance, in Mississippi, March 1863, the Confederate Quartermaster in Jackson, Major Livingston Mims, relied on numerous factories to supply his depot. When considering clothing, the Jackson Manufactory made 5,000 garments weekly. Another five factories, the Bankston, Columbus, Enterprise, Natchez, and Woodville Factories, made together 5,000 garments per week. All these garments were collected, indiscriminately consolidated and re-distributed to the army without making any distinctions about their tailoring or origins. The only factor noted about each garment was its cost to the government, because that would determine the price charged to the soldier’s clothing account. Each factory charged slightly different prices for its jackets, pants and other items; and, these prices were scrupulously noted by the quartermaster. Aside from the price, distinctions were seldom noted (occasionally, the garment’s fabric type or color was annotated), and when a requisition for a given number of jackets and pants was filled, the brigade drawing the clothing might get boxes of jackets that had been made at the Jackson, Natchez and Bankston factories, and pants that had been made at the Enterprise, Woodville and Columbus factories. The jackets and pants may all have differed slightly and even though the brigade had all drawn new, clean clothing, its appearance would likely have been far from “uniform.” This accounts for why Confederate inspectors often noted that the troops were well-clothed (even in government issue uniforms), but that their dress was “indifferent” or “not uniform.”[68] It also explains why it is nearly impossible to say where exactly the surviving uniforms were made.

A few things are certain, however. Factory clothing is generally identifiable as such, based on its pattern, the seamstress workmanship, and the materials. Clothing records attest to general issues to both regiments and individuals, by time and place, proving that quartermaster garments were distributed within identified areas. Additionally, many of the surviving uniforms have good provenance to the areas they would most likely have originated. Those surviving uniforms without provenance often have enough characteristics about them to identify them as belonging to a region where similar cloth or clothing was manufactured or issued. By piecing together all the available evidence, one can draw some probable conclusions about where the uniforms originated. The uniforms selected for this study have been evaluated accordingly. I have arranged the uniforms starting with the earliest known examples, and starting with the western Lower South (Mississippi, East Louisiana and Alabama), and continuing to the eastern Lower South (Georgia, Florida and South Carolina).

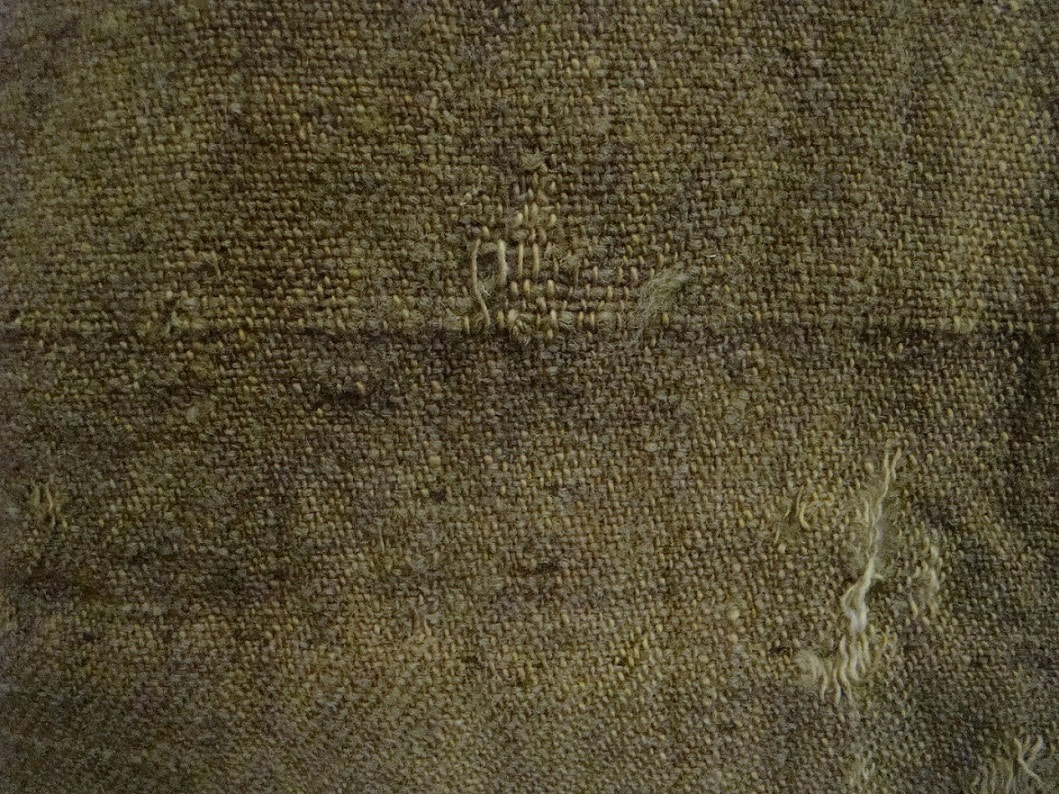

Few specifics are available about the products of the smaller Mississippi and Alabama factories. One of the more prominent factories, however, was Edward McGehee’s Woodville, Mississippi factory. The Memphis Daily Appeal, August 14, 1862, wrote, “A Noble Example. E. McGehee, proprietor of the Woodville Factory, we are informed, has been and is still furnishing the quartermaster's department, for the use of the army, with a good article of Lowels at twenty-five cents a yard, and linseys at seventy-five cents a yard. He refuses the current and exorbitant prices demanded by the haberdashers, hucksters and Jew extortioners, and sells to the government to clothe its brave and sometimes almost naked heroes at one-half the market price. What a noble example of disinterested and lofty patriotism! Mississippian.”[69] Some descriptions of McGehee’s basic uniform cloth have survived. One is from Mississippi cadet David Holt in the fall of 1861. Holt’s home guard company uniforms were made with cloth supplied by McGehee’s mill which Holt described as “brown factory jeans.”[70] McGehee’s sales receipts to the Confederate quartermaster in 1862 and 1863 note that he furnished them with “colored jeans and linseys,” “dyed jeans and linseys,” and “white jeans and linseys.” The dyed and colored fabrics may have been the same brown color that Holt described.[71]

Holt went on to describe McGehee’s fabrics during the period from the fall of 1861 to the spring of 1862 in more detail stating, “This factory made unbleached cotton cloth in two grades, one four ounces and the other eight ounces to the yard. The heavy quality was used for jeans out of which coats and trousers were made. The ladies dyed all the cloth with sweet-gum bark, which gave it a bluish-gray tint. The outer garments were lined with the eight-ounce cotton cloth. The underwear was made from the four-ounce cloth. In this manner the soldier was clad all in one color.” Also, “A good lesson was learnt in the effectiveness of color protection, as our bluish-gray was almost invisible to the enemy, particularly when lying down. The two [local] tailors cut, without pay, every soldier’s garments to fit.”[72]

Two jackets survive with both a Mississippi provenance and the above described bluish-gray color. The first of these is a Confederate jacket was brought home by a Federal soldier as a souvenir that he found on the Labadieville, Louisiana battlefield. This was a jacket left behind by a member of Company H, 1st Mississippi Artillery from the battle on October 27, 1862. As the regiment had been organized in the late summer of that year, this was probably the mustering-in jacket that Company H had received from the local area before leaving home. Nonetheless, the jacket may be representative of the type of cloth made in McGee’s factory and dyed with sweet-gum bark.

The jacket’s basic jean cloth now appears a medium-dark blue color, but the present owner, Don Troiani, believes it to have originally been a dark, blue-gray. The collar is adorned on either side with crossed cloth cannon barrels cut from red cloth. Likewise, each shoulder has a red cloth bar, as well. The entire outer edge of the jacket and collar have red worsted cording, and this same cording has been applied to the cuffs as pointed facings. It has no topstitching around the edges. Finally, each sleeve, below the elbow, has an inverted, upward pointing, yellow silk chevron. There are buttons on the cuffs and nine Federal eagle “I” buttons on the front.[73] Interestingly, a firm named Clark & Joseph sold “2 Doz Blue Jackets @ $55.00 a dozen,” ($4.58 each) to the quartermaster at Jackson, Mississippi on September 25, 1862.[74] Perhaps Clark & Joseph made the blue, Company H jacket. It may also be the case that the basic fabric was dyed to a bluish-gray color with sweetgum bark, as recounted beforehand by David Holt.

The second of these jackets resides in the University of Mississippi collection. William Decatur Howell, Company I, 3rd Mississippi Cavalry wore this jacket. Howell had enlisted in July 1863 and was killed at the Battle of Atlanta in July 1864. The dark, blue-gray jacket has an eight-button front, two outside breast pockets, two-piece sleeves, and utilizes Federal enlisted “I” buttons. The jacket may have been made and issued in Mississippi. Its color suggests that it may likewise be an example of sweetgum bark dyed fabric.[75]

The industrial centers in Atlanta and Columbus, Georgia were the largest in the Lower South that remained under Confederate control by the summer of 1862. Their combined textile production, however, was not sufficient to supply all the armies of the Lower South. Nonetheless, Columbus was at times expected to supply troops outside of her district: namely Mississippi, Virginia, and even far away Arkansas. Given a dearth of large factories in the Lower South, it fell upon the numerous small textile mills to supply the armies with clothing. Their aggregate production furnished quartermasters with adequate quantities.

These small factories left their mark upon the character of Confederate depot uniforms in one peculiar way: there was a lack of uniformity within the patterns of jackets and trousers. Each small clothing factory used its own distinctive patterns, and its own particular cloth, linings and buttons, the latter contingent upon what it could obtain at any given time. The jackets, for instance, were uniform in only one respect: they were short, single-breasted, with standing collars. Other than that, there was tremendous latitude from factory to factory as to how the jackets were made. They differed in how many buttons were used to close the front of the jacket; some had colored trim facings and some did not; the placement of pockets differed widely; and, the subtle nuances of the cut are noticeable enough to determine that they were made at different places. Eventually, the government assumed more manufacturing responsibility, and production operations were consolidated and became larger. Along with the latter trend, the quartermaster general fostered uniformity in how clothing and equipment was made. But this level of systematic efficiency was not achieved until 1864, and so, the uniforms of the Lower South reflect the indifferent uniformity of numerous factories, each making its own variants of jackets and pants.

Some of the names of the Lower South’s clothing factories have survived, along with records of their production. Likewise, numerous jackets and pants survive that undoubtedly came from the small factories of the region. But since the factories did not mark their products, we may never know exactly what factory made a specific jacket or pair of pants. Additionally, due to the nature of procurement, collection and distribution, the possibility of pinpointing the exact origin of a surviving uniform is improbable.