The Confederate Depot Sack Coat: An Overlooked Garment

by Fred Adolphus, 4 August 2013; updated 4 September 2019

The Confederate depot sack coat has been overlooked by Confederate uniformologists, perhaps with good reason: few were made. Nonetheless, the military sack coat was issued on sufficient enough quantities to warrant a closer look by uniform buffs. This study offers some insights to the seldom-made, but well-liked Confederate garment.

The citizen sack coat was very popular with Southerners. Henry Orr, of the 12th Texas Cavalry, underscored these sentiments in a letter home to his family in September 1863. Therein, he asked them to send him a jeans frock coat, "... or sack of the loose wrapper style; one similar to the one you sent me last fall..." Its popularity might have inspired greater production had the coat not required more fabric than the cloth-saving jacket. When manufacturers did produce a military version of the sack coat, they settled on a compromise: a cross between the long, loose citizen-style coat with a fall collar, and the close-fitting, shorter, stylish military jacket with a stand collar.

The citizen sack coat was very popular with Southerners. Henry Orr, of the 12th Texas Cavalry, underscored these sentiments in a letter home to his family in September 1863. Therein, he asked them to send him a jeans frock coat, "... or sack of the loose wrapper style; one similar to the one you sent me last fall..." Its popularity might have inspired greater production had the coat not required more fabric than the cloth-saving jacket. When manufacturers did produce a military version of the sack coat, they settled on a compromise: a cross between the long, loose citizen-style coat with a fall collar, and the close-fitting, shorter, stylish military jacket with a stand collar.

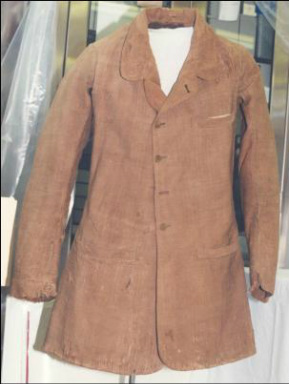

Picture 1: The sky blue, homespun, sack coat of Captain Julius William Storey, 12th Texas Infantry has the long skirt characteristic of the citizen-style sack coat. This coat represents the ideal for comfort versus style, and Storey probably wore this coat in camp, while off-duty. Storey also had a double-breasted, cadet gray frock coat that he wore for official duty. Image courtesy of the Author, Texas Heritage Museum, Texas Division, United Daughters of the Confederacy Collection, Hillsboro College.

Pictures 2-4: The two images on the left depict workers in a Confederate foundry, thought to be in Houston, Texas in 1864. They wear the typical citizen sack coat with its open collar and long skirt. The image on the right shows the standard Federal Army blouse: a sack coat made loose and longer than its Confederate counterpart. The Federal military blouse incorporated a closed collar, instead of the open citizen collar, but it retained citizen-style fall collar. There was some variance in the length of Federal sack coats, but they always extended at least to the bottom of the cuff, and occasionally a bit lower. Images courtesy of Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III photograph collection, and the U.S. Army, Center of Military History, Quartermaster Museum.

Pictures 5-7: Private Burton Marchbanks, Company E, 30th Texas Cavalry, wore a butternut, homemade citizen style paletot coat, (similar to a sack coat). The flair necessary to fit comfortably over the hips is apparent in these images. This tailoring characteristic required a generous quantity of fabric: an unnecessary extravagance for government made clothing. Images courtesy of the Author, Layland Museum, Cleburne, Texas.

While most military clothing contractors, and all depots adhered to the quartermaster-regulation jacket, some manufacturers opted for the military-style sack coat. The depot system, relying on the production of numerous independent clothing contractors to supplement their own fabrication in government shops, issued these sack coats, along with an indifferent plenitude of jackets provided by diverse small factories. Remarkably, these sack coats share striking commonalities with one another. They are all made of domestic fabric (jeans, satinet, and cassinet), and they are all domestically dyed, now appearing tan or butternut-colored. This strengthens the thesis that small contractors made them. Had government shops made them, some would inevitably been made of government-procured, cadet gray kersey. Of six surviving originals that I have examined in pictures, they have the following characteristics:

1. Length of the Body: Only one extended down as low as the bottom of the cuff (that being Brooke's coat). The body length on all others is above the cuff line (like a jacket). The difference here is that the body length on most jackets is about 65-80% of the sleeve length, whereas on sack coats the body length is 75-90% of the sleeve length (a little longer than most jackets). These figures clearly show that there is overlap in the dimensions, but the general trend is for a longer sack coat body with more flair in the hips and buttocks. Furthermore, the Southern military sack coat differs from its Federal counterpart in that the Union sack coat body always extends at least as low as the cuff, and sometimes even lower. The Confederate sack coat is somewhat similar to the shell jacket.

2. Button Placement: While the buttons on jackets are fairly evenly spaced from top to bottom, the bottom button on the sack coat is generally set at about navel, or elbow height, which leaves a wide space between the navel and the bottom edge of the coat without buttonholes. This placement provides the illusion of a longer coat. The sack coat also has generally less buttons overall than a jacket (usually only four).

3. Body Pieces: Sack coats tend to have four-piece bodies, whereas jackets tend to have six-piece bodies. By nature of their length, the sack coat must be cut more generously at the bottom edge so that it can fit easily over the top on the hips.

4. Standing Collar: In contrast to the collar of the citizen, and even the Union army sack coat, the Confederate quartermaster sack coat incorporated a standing collar. Thus the coat retained its military bearing and similarity to other Confederate tunics.

5. Most depot sack coats had only four or five buttons (less than many jackets), and usually had at least one exterior pocket. Interestingly, all the surviving sack coats are made of domestic fabric (jeans, satinet, and cassinet), and were domestically dyed, now appearing tan or butternut-colored.

Having defined a Confederate depot sack coat, the following explanation is necessary to put this garment within the context of Confederate quartermaster clothing. Neither manufacturers nor quartermasters drew the slightest distinction between the typical, tight fitting jacket and the looser sack coat. Both were carried in the inventories as “jackets.” Furthermore, the Confederate depot sack coat was not even a true sack coat. A true sack coat of the period was loose with a fall collar, and its length extended well below the bottom of the cuff. Yet, the Confederate depot sack coat differs just enough from the typical jacket to slightly resemble a sack coat. Its salient characteristics bear this out.

There are a modest number of surviving Confederate military sack coats that offer detailed analysis. Additionally, there are some photos, drawings and paintings that provide insights about this garment. In some cases, we have the coat's provenance, and know who wore it, where it was worn and where it was issued. In many cases, the history ranges from fragmentary to non-existent. Enough provenance remains for us to conclude that soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia got these coats late in the war, and that some were issued in the Western theater since early in war. Several coats without provenance are similar enough to suggest they may have been made by the same factory and issued in the same region. In any case, while the Confederate sack coat may not be typical of the "Johnny Reb" icon, it foreshadowed a growing trend in military uniforms: the rise of comfortable, practical field clothing over tight-fitting stylish military tunics.

1. Length of the Body: Only one extended down as low as the bottom of the cuff (that being Brooke's coat). The body length on all others is above the cuff line (like a jacket). The difference here is that the body length on most jackets is about 65-80% of the sleeve length, whereas on sack coats the body length is 75-90% of the sleeve length (a little longer than most jackets). These figures clearly show that there is overlap in the dimensions, but the general trend is for a longer sack coat body with more flair in the hips and buttocks. Furthermore, the Southern military sack coat differs from its Federal counterpart in that the Union sack coat body always extends at least as low as the cuff, and sometimes even lower. The Confederate sack coat is somewhat similar to the shell jacket.

2. Button Placement: While the buttons on jackets are fairly evenly spaced from top to bottom, the bottom button on the sack coat is generally set at about navel, or elbow height, which leaves a wide space between the navel and the bottom edge of the coat without buttonholes. This placement provides the illusion of a longer coat. The sack coat also has generally less buttons overall than a jacket (usually only four).

3. Body Pieces: Sack coats tend to have four-piece bodies, whereas jackets tend to have six-piece bodies. By nature of their length, the sack coat must be cut more generously at the bottom edge so that it can fit easily over the top on the hips.

4. Standing Collar: In contrast to the collar of the citizen, and even the Union army sack coat, the Confederate quartermaster sack coat incorporated a standing collar. Thus the coat retained its military bearing and similarity to other Confederate tunics.

5. Most depot sack coats had only four or five buttons (less than many jackets), and usually had at least one exterior pocket. Interestingly, all the surviving sack coats are made of domestic fabric (jeans, satinet, and cassinet), and were domestically dyed, now appearing tan or butternut-colored.

Having defined a Confederate depot sack coat, the following explanation is necessary to put this garment within the context of Confederate quartermaster clothing. Neither manufacturers nor quartermasters drew the slightest distinction between the typical, tight fitting jacket and the looser sack coat. Both were carried in the inventories as “jackets.” Furthermore, the Confederate depot sack coat was not even a true sack coat. A true sack coat of the period was loose with a fall collar, and its length extended well below the bottom of the cuff. Yet, the Confederate depot sack coat differs just enough from the typical jacket to slightly resemble a sack coat. Its salient characteristics bear this out.

There are a modest number of surviving Confederate military sack coats that offer detailed analysis. Additionally, there are some photos, drawings and paintings that provide insights about this garment. In some cases, we have the coat's provenance, and know who wore it, where it was worn and where it was issued. In many cases, the history ranges from fragmentary to non-existent. Enough provenance remains for us to conclude that soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia got these coats late in the war, and that some were issued in the Western theater since early in war. Several coats without provenance are similar enough to suggest they may have been made by the same factory and issued in the same region. In any case, while the Confederate sack coat may not be typical of the "Johnny Reb" icon, it foreshadowed a growing trend in military uniforms: the rise of comfortable, practical field clothing over tight-fitting stylish military tunics.

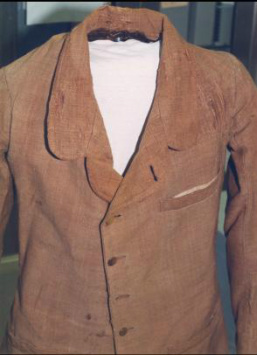

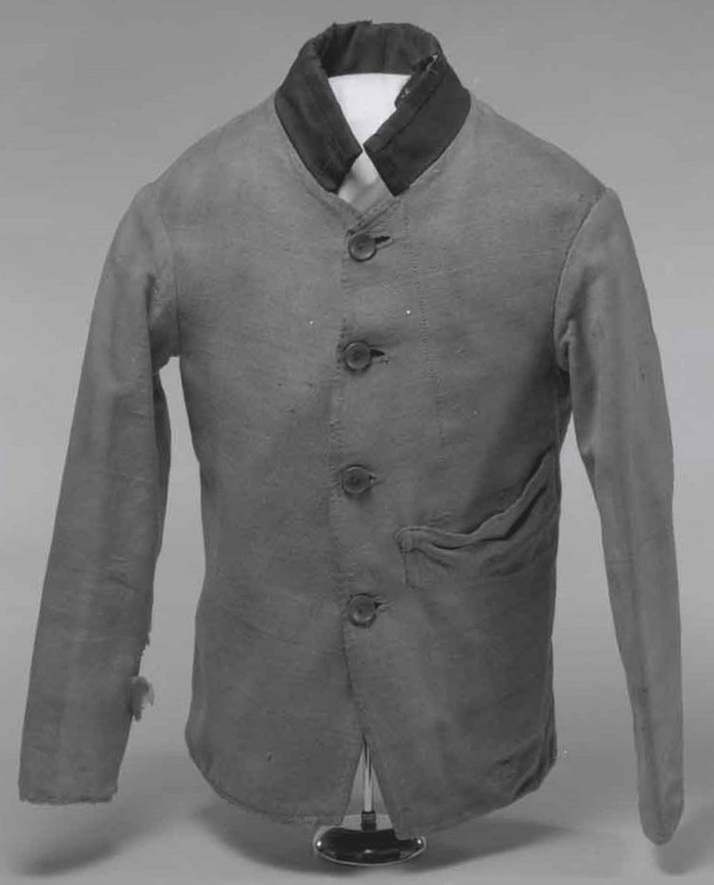

Pictures 8: Corporal T.V. Brooke's sack coat was issued by the Richmond Depot late in the war, and he wore it at Appomattox. Brooke served with the 3rd Company, Richmond Howitzers. The light brown jeans cloth is typical of depot sack coats, as well as the standing collar and four-button front. The black-faced collar is unusual, and it is long for a Confederate sack coat, extending down to the cuffs. Following the trend towards practicality, the coat has an exterior pocket. The garment has also been simplified by using one-piece sleeves, and a four-piece body. Finally, the coat retains all four of its buttons: plain horn or composition, two-hole buttons. Image courtesy of the Museum of the Confederacy.

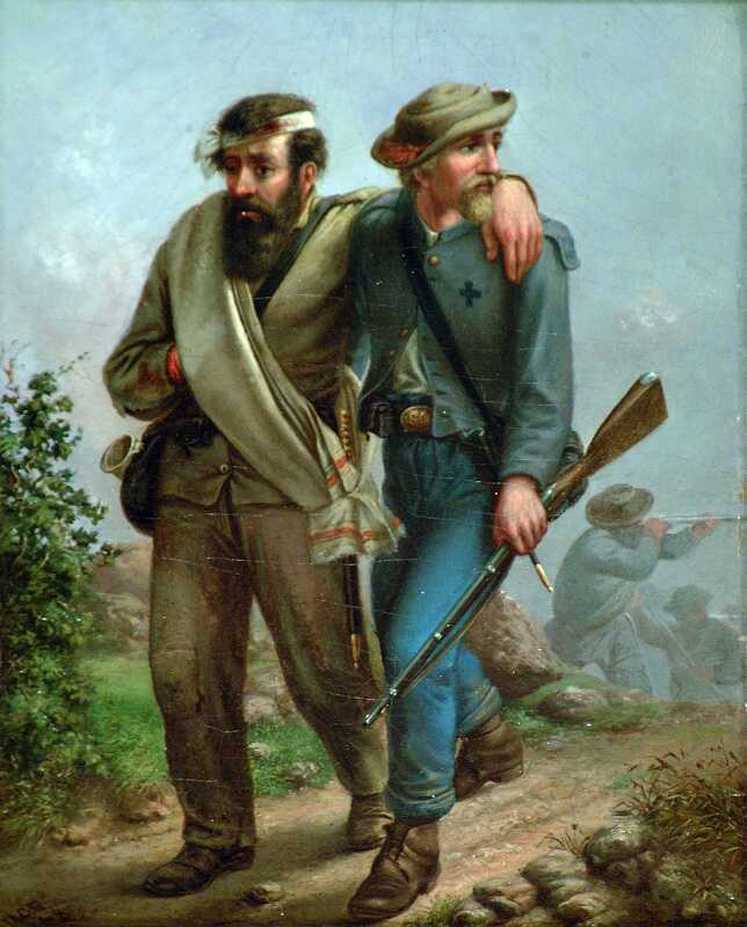

Picture 9: An oil painting by Allen C. Redwood in 1868, depicting a Maryland soldier helping a wounded comrade walk from the battlefield, offers another perspective of sack coats used in the Army of Northern Virginia. Redwood served as a Confederate officer in this army, and rendered numerous drawings and paintings of Confederate soldiers soon after the war. Redwood's art closely reflects what the soldiers actually wore, and this color painting can be trusted to reflect an accurate picture of a sack coat. The sack coat conforms to the Brooke coat in its overall length and its light brown color. Redwood is probably mistaken about adding shoulder straps to the coat, and showing a low positioned button close to the bottom hem, but in every other respect he accurately portrays a late war Confederate sack coat. Image courtesy of the U.S. Army, Center of Military History.

Picture 10: A very distinct image taken in occupied Richmond, Virginia, April 1865, depicts a group of black freedman, some of them wearing Confederate uniforms. Those wearing the uniforms may have acquired them from government store houses at the fall of Richmond, or they may have been serving in Confederate Army in some capacity. It is possible that may have been in the Confederate "Black Brigade," formed in the last months of the war, that consisted of two or three battalions of infantry. In any case, one of the freedmen wears a Confederate military sack coat and matching fabric pants. The coat has four brass military buttons, but no exterior breast pocket. It is similar to the Brooke coat in that the bottom edge extends almost down to the cuff. The stand collar has no contrasting facing. What is certain about this coat is that it represents the type used by the Army of Northern Virginia at the close of the war. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

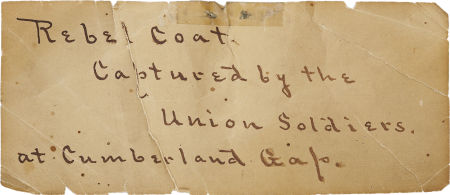

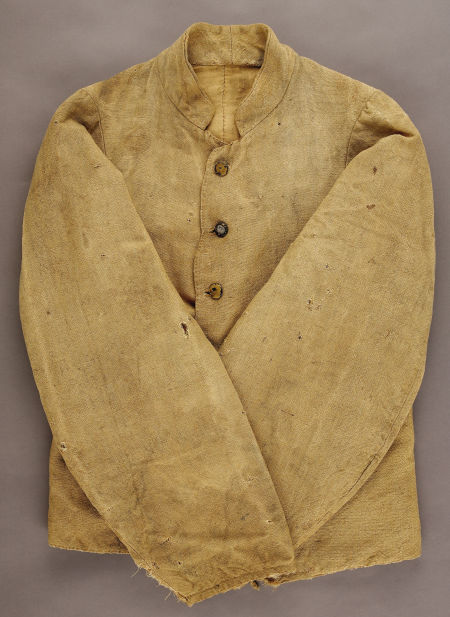

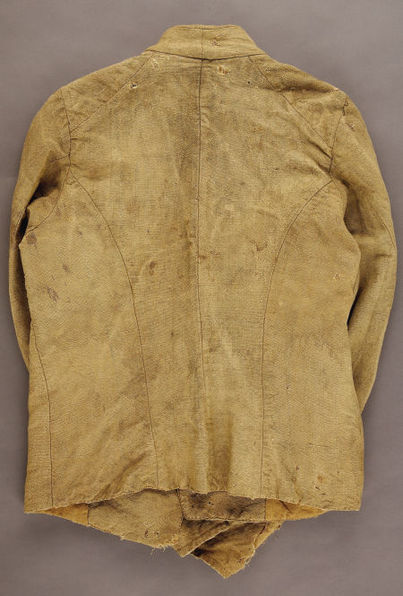

Pictures 11-16: Heritage Auctions of Dallas, Texas advertised a Confederate sack coat from the Western theater in about 2011. Its provenance is limited to an old label inside the coat inscribed, "Rebel Coat Captured by the Union Soldiers at Cumberland Gap." The Cumberland Gap sack coat exhibits some early characteristics that include a six-button front, and a six-piece body. The collar is two-piece, inside and out. These characteristics were later usually simplified to a four-button front and four-piece body. Otherwise, the one piece sleeves, exterior breast pocket, and length are typical of Confederate sack coats. The bottom edge is well above the cuff line.

The provenance, such as it is, suggests that this is a Western depot coat. Last of all, the coat retains at least three of its buttons: all of which appear to be wooden, two-hole buttons. Images courtesy of the Heritage Auctions.

The provenance, such as it is, suggests that this is a Western depot coat. Last of all, the coat retains at least three of its buttons: all of which appear to be wooden, two-hole buttons. Images courtesy of the Heritage Auctions.

Pictures 17-18: Another Western sack coat resides in the New York State Military Museum with excellent provenance. Accordingly, it was a "Confederate jacket" worn by Captain James Hughes, 4th New York Heavy Artillery, while he was a prisoner at Andersonville. The coat is in poor condition, and may have looked quite different before was worn to flinders and repaired in several spots. To start with, coat follows the essential characteristics of depot sack coats. It is made of domestic jeans, or satinet. The color, which probably faded from gray, is now tan. It has an exterior pocket on the left breast. The bottom button was set considerably above the bottom edge of the coat. Only one of the original buttons remains intact: a black horn, two-hole button. Finally, the body appears to be four-piece, and flairs over the hips. However, the coat also displays anomalies. It has two-piece sleeves; the coat extends well below the cuff line; and it has a five-button. Additionally, the collar is missing, if indeed it ever had one, and the bottom front edge is cut away, sweeping up and inwards. Considering the number of repairs and patches on the coat, it seems likely that the standing collar worn out, and was simply removed and the neck hole sewn closed. Likewise, the front was probably originally of one uniform length, and was cut away due to wear, and repaired by simply closing the seam where the fabric was still intact. In any case, Hughes' Confederate coat provides us with another example of a mid-war, Western depot, sack coat. Images courtesy of the New York State Military Museum.

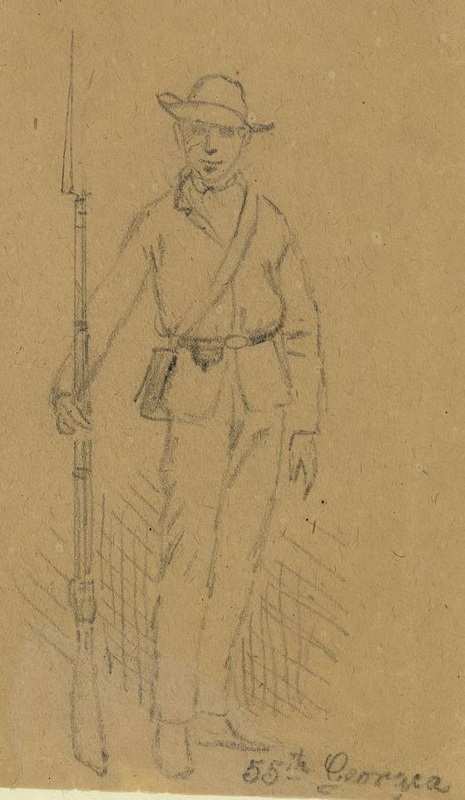

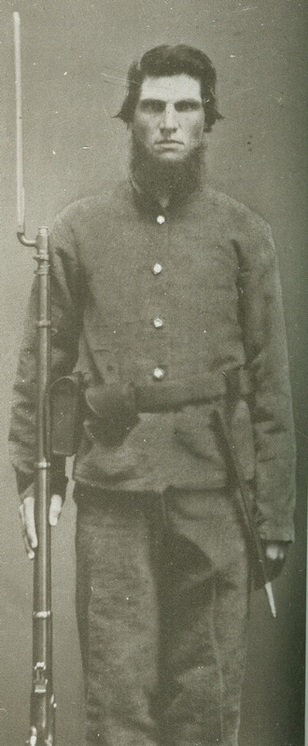

Pictures 19-20: The last well-documented Western depot sack coat herein (image on left) is from the Civil War sketch artist, Alfred R. Waud. Waud sketched a soldier of the 55th Georgia Infantry wearing one. The soldier is fully armed and accoutered as a regular Confederate soldier. His sack coat is the correct depot length, being cut well above the cuff line, but Waud neglected to draw buttons on the coat. The collar is also laid flat in front, giving the appearance of an open collar coat, but it stands in the rear, suggesting that the soldier intentionally laid the stand-collar down. The regiment served in East Tennessee from the summer of 1862 until September 10, 1863, when most of the regiment was captured at Cumberland Gap. The regiment was exchanged and spent the rest of the war guarding prisoners in Georgia and the Carolinas. Another representative depot sack coat can be observed in the image (at right) of Alabama Confederate, John T. Davis, whose regimental affiliation is unknown. His sack coat has the usual traits: standing collar; four-button front with the bottom button at elbow level; and, the length well above the cuff line. The sleeves appear to be one-piece. The coat lacks the

usual exterior breast pocket, but a bulge in the bottom if the jacket indicates that it has an interior pocket that extends to the bottom edge. The coat also has brass military buttons. Images courtesy of the Library of Congress, and the U.S. Army Military History Institute.

usual exterior breast pocket, but a bulge in the bottom if the jacket indicates that it has an interior pocket that extends to the bottom edge. The coat also has brass military buttons. Images courtesy of the Library of Congress, and the U.S. Army Military History Institute.

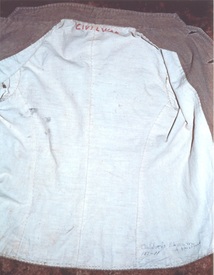

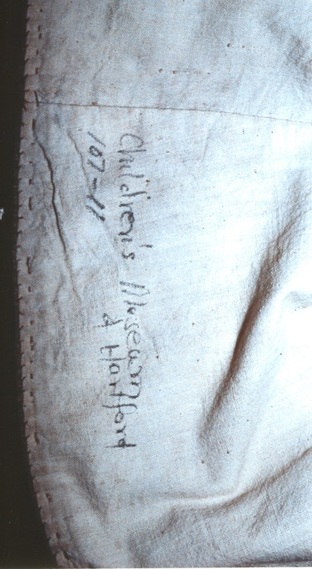

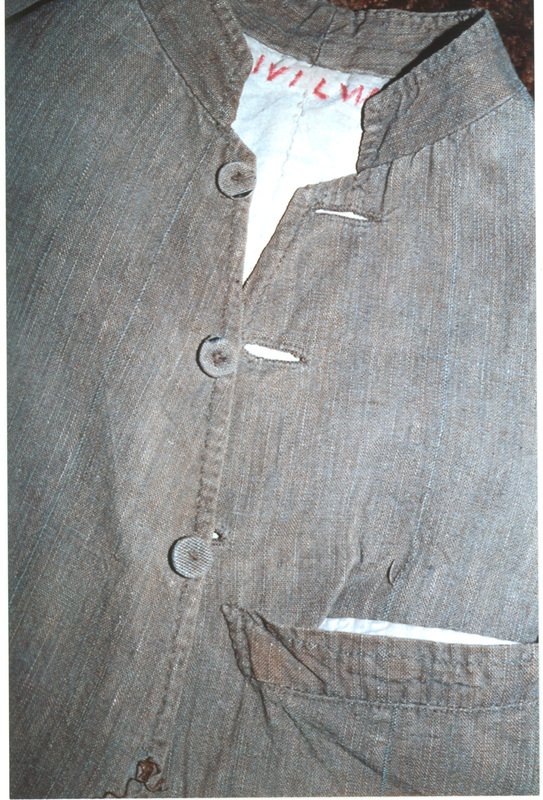

Pictures 21-28. A few authentic sack coats have survived, albeit without their wartime provenance intact. One found its way to the theatrical prop department of the Children's Museum of Hartford, Connecticut. Renowned collector, Dr. Bob Jaffee "rescued" it and generously shared it through several publications. The coat then passed to the Gettysburg National Battlefield Park collection, and resides at present. The "Jaffee collection" coat is a depot product in every respect: made of tan-colored, domestic fabric; having an exterior left breast pocket, a four-piece body and two-piece sleeves; the length ending above the cuff line; a standing collar; and, a four-button front with the bottom button set at elbow height. All four of its buttons are intact: black horn, four-hole buttons covered with tan fabric. The coat is lined with unbleached osnaburg, and the collar is two-piece, inside and out. The Jaffee collection coat is remarkably similar to the remaining coats left to be examined in this study. Images courtesy of Dr. Bob Jaffe and the Author, National Parks Service, Gettysburg Battlefield.

Pictures 29-35: Shannon Pritchard, of Old South Military Antiques, shared images of another quintessential depot sack coat in 2009. Regrettably, the coat's history is lost, but its chief characteristics correspond to a typical, late-war, Confederate depot product. It mirrors the Jaffee collection coat in every way except that is is made of a jeans weave fabric and has a one piece collar, inside and out.

Mr. Pritchard believes the four Virginia state buttons, now on the coat, may have been later additions. The Pritchard and Jaffee collection coats are similar enough to suggest a common manufacturer. Images courtesy of Shannon Pritchard, Old South Military Antiques.

Mr. Pritchard believes the four Virginia state buttons, now on the coat, may have been later additions. The Pritchard and Jaffee collection coats are similar enough to suggest a common manufacturer. Images courtesy of Shannon Pritchard, Old South Military Antiques.

Pictures 36-39: Yet another coat, almost identical to those in Jaffee's and Pritchard's collections, is the "Purdum" sack coat, that now

resides in the Ross County Historical Society, Ohio. The provenance is sketchy, but as far as it goes, a Union soldier named Purdum brought the sack coat home to the North as a Confederate war souvenir. Only two of its four buttons remain intact: a Louisiana pelican, and a Federal eagle. The coat is made of a jeans weave material, and collar is two-piece, inside and out. The facing lapel piece, at the top, extends along the inner collar all the way to the back lining pieces. This is, incidentally, the case with Pritchard's coat, but not with Jaffee's or the Cumberland Gap coats. Images courtesy of Ross County Historical Society, Ohio.

resides in the Ross County Historical Society, Ohio. The provenance is sketchy, but as far as it goes, a Union soldier named Purdum brought the sack coat home to the North as a Confederate war souvenir. Only two of its four buttons remain intact: a Louisiana pelican, and a Federal eagle. The coat is made of a jeans weave material, and collar is two-piece, inside and out. The facing lapel piece, at the top, extends along the inner collar all the way to the back lining pieces. This is, incidentally, the case with Pritchard's coat, but not with Jaffee's or the Cumberland Gap coats. Images courtesy of Ross County Historical Society, Ohio.

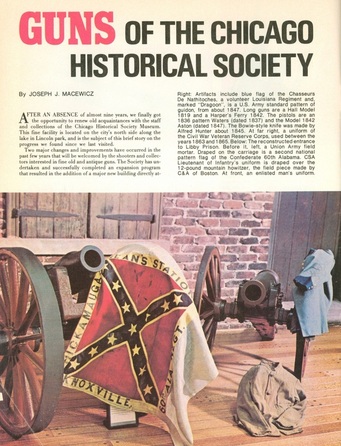

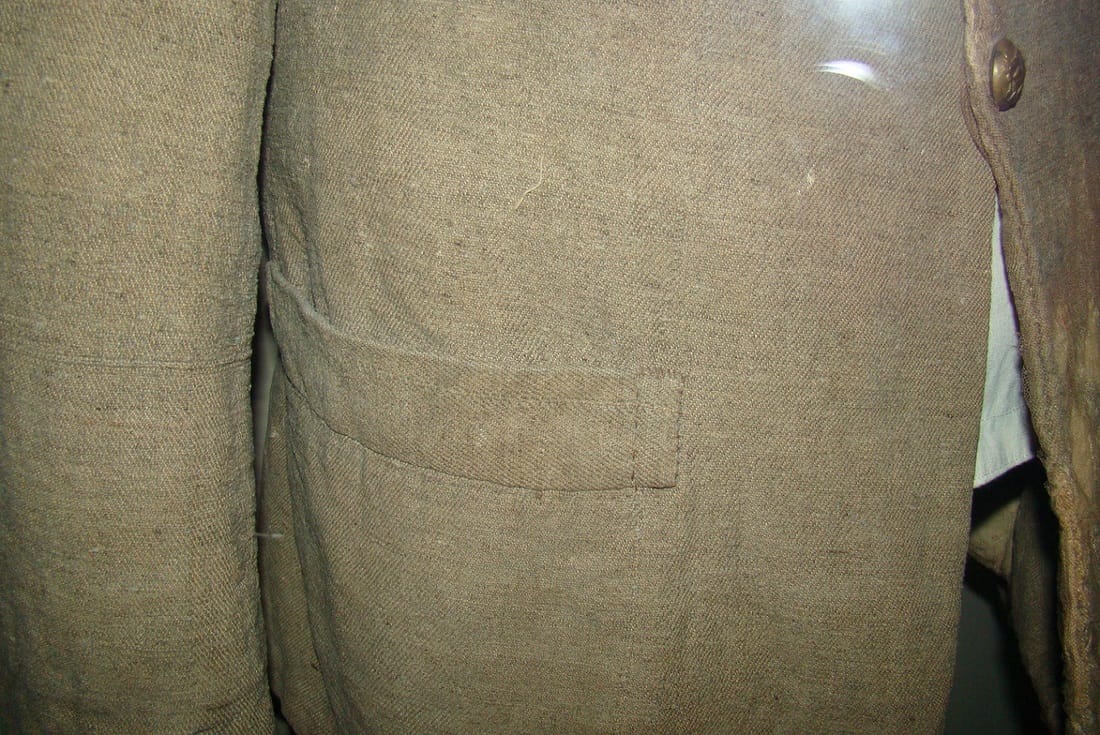

Pictures 40-42: An authentic sack coat featured in a magazine article entitled "Guns of the Chicago Historical Society," by Joseph J. Macewicz is shown above. The author spruced up his firearms article with a Confederate flag and two coats (one of which is a butternut sack coat). Since at least 2018 (and probably several decades before), the coat resides in the Milwaukee Public Museum. The enlisted sack coat conforms to the others in this study in color, cut and material. It is draped against a backdrop at an odd angle, but seems to have a four-button front, and the length does not appear to extend beyond the cuffs. It has the usual exterior, left breast pocket. It also has military brass buttons, and the sleeves are of two-piece construction. The lining is unbleached osnaburg. Images courtesy of Guns Magazine, November 1975, Vol. XX, No. 5-11, Publisher's Development Corp., Skokie, Illinois.

The final sack coat (featured below) is one worn by Private George W. McDill, Company C, 9th Tennessee Infantry, “The Southern Confederates.” The jacket is part of the Pink Palace collection, Memphis, Tennessee, and as of October 2016 was on loan to the Mud Island Museum in Memphis.

McDill, who had enlisted on July 1, 1861, was present with his command until he was wounded at Perryville. At that time, he was carried as absent until he returned during the March-April muster period. He was captured in Tipton County, Tennessee, was listed as a prisoner of war on April 3, 1863, and he was exchanged on April 28, 1863 either at City Point, Virginia or at Vicksburg, Mississippi. He rejoined his command and served with his regiment through the Western and Carolina campaigns, being paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865. Family lore has it that McDill wore the sack coat when he was wounded at Perryville, but given that most surviving jackets have provenance to the time and place of the wearer’s last service, it is more likely that the sack coat was issued to McDill during the last six months of his service, most likely from a quartermaster in Georgia or the Carolinas.

Since I was only able to view the coat through the glass of the vitrine, I have relied on Les Jensen’s observations (who examined the coat first hand) to round out my notes. The coat has a four-piece body (two front and two back pieces), one-piece sleeves, and a two-piece collar. The lapel facings are very wide. It has four buttonholes and three remaining Confederate staff officer, eagle buttons, Tice # CS275A1 without backmarks. It has two lower, exterior pockets on the front pieces. The pocket openings are positioned well below the bottom button hole. The overall color of the coat is tannish-gray. The basic fabric is a woolen-cotton jeans with one weft over two and under one warp, and one warp over one and under two weft. The warp is an unbleached white and the weft is a tannish-gray color. The lining is made of unbleached osnaburg. The jacket has no topstitching around the body or cuffs, but the collar has topstitching. The thread colors used in the construction are tan and light brown. All images courtesy of the author.

McDill, who had enlisted on July 1, 1861, was present with his command until he was wounded at Perryville. At that time, he was carried as absent until he returned during the March-April muster period. He was captured in Tipton County, Tennessee, was listed as a prisoner of war on April 3, 1863, and he was exchanged on April 28, 1863 either at City Point, Virginia or at Vicksburg, Mississippi. He rejoined his command and served with his regiment through the Western and Carolina campaigns, being paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865. Family lore has it that McDill wore the sack coat when he was wounded at Perryville, but given that most surviving jackets have provenance to the time and place of the wearer’s last service, it is more likely that the sack coat was issued to McDill during the last six months of his service, most likely from a quartermaster in Georgia or the Carolinas.

Since I was only able to view the coat through the glass of the vitrine, I have relied on Les Jensen’s observations (who examined the coat first hand) to round out my notes. The coat has a four-piece body (two front and two back pieces), one-piece sleeves, and a two-piece collar. The lapel facings are very wide. It has four buttonholes and three remaining Confederate staff officer, eagle buttons, Tice # CS275A1 without backmarks. It has two lower, exterior pockets on the front pieces. The pocket openings are positioned well below the bottom button hole. The overall color of the coat is tannish-gray. The basic fabric is a woolen-cotton jeans with one weft over two and under one warp, and one warp over one and under two weft. The warp is an unbleached white and the weft is a tannish-gray color. The lining is made of unbleached osnaburg. The jacket has no topstitching around the body or cuffs, but the collar has topstitching. The thread colors used in the construction are tan and light brown. All images courtesy of the author.

In terms of clothing produced, procured and issued, the “sack coat” fell into the category of a jacket and was considered such by those who made it, the depot that issued it, and the men who wore it. Its distinction as a sack coat today has been conferred by uniformologists, not soldiers of the time. In any case, few sack coats were manufactured, and there are but a handful surviving today. Nonetheless, this peculiar cut is indicative of the desire to have a slightly longer jacket that was loose enough to fit comfortably over the tops of the hips, and stay well-tucked under the soldier’s waist belt and accoutrements. There are some quartermaster reports that may reflect the desire for this type of jacket. Vernon K. Stevenson, in charge of Confederate quartermaster operations in Tennessee during 1861-62, specified that clothing conform to the following guidelines in September 1861. Pants and jackets were to be made of heavy brown or gray jeans; the jackets where to be roundabout, Army jackets (or pea jackets); both lined throughout and having side and vest pockets; and, the jackets were to extend four inches past the pants waistband, and be made large enough to fit over a vest or shirt. The remark about the jacket's length may indicate that the tailoring was to approximate the cut of the typical Confederate depot sack coat.[1] Captain E.C. Wharton, Chief of the Houston, Texas Clothing Bureau, alluded to this same topic on May 16, 1863. Wharton asked that if imported, ready-made clothing was provided, the jackets be, “…Grey Cloth to come below hips & with pockets.”[2] In this regard, the sack coat foreshadowed a growing trend in military uniforms: the rise of comfortable, practical field clothing instead of tight-fitting, stylish military tunics.

Bibliography:

[1] Brooks, Ross, Clothing of the Tennessee Volunteer, 1861, Company of Military Historians Journal, Volume 46, No. 2, Summer 1994, pages 71, column 2, and 72, column 1.

[2] Captain Edward C. Wharton, Chief Quartermaster, District of Texas, records 1862-1864, NARA, Record Group 109, Confederate Inspection Reports, M935, Reel 8, 89-J.41 through 158-J.41, this reference 113-J.41, Estimate for Clothing and Clothing Material for 2nd Year Commencing October 8, 1863, Eastern Mil Sub District of Texas, E.C. Wharton, Captain & AQM, Houston, Texas, May 16, 1863.

My thanks go out to all the museums, as named in the photo credits, that helped me with my research for this article. All images listed in this article as "courtesy of the author" are under copyright protection of Adolphus Confederate Uniforms, and may not be reproduced without the author's consent. Some of the images are in the public domain and there are no restrictions on their use. Use of other images would require the consent of the museum that furnished them.

Bibliography:

[1] Brooks, Ross, Clothing of the Tennessee Volunteer, 1861, Company of Military Historians Journal, Volume 46, No. 2, Summer 1994, pages 71, column 2, and 72, column 1.

[2] Captain Edward C. Wharton, Chief Quartermaster, District of Texas, records 1862-1864, NARA, Record Group 109, Confederate Inspection Reports, M935, Reel 8, 89-J.41 through 158-J.41, this reference 113-J.41, Estimate for Clothing and Clothing Material for 2nd Year Commencing October 8, 1863, Eastern Mil Sub District of Texas, E.C. Wharton, Captain & AQM, Houston, Texas, May 16, 1863.

My thanks go out to all the museums, as named in the photo credits, that helped me with my research for this article. All images listed in this article as "courtesy of the author" are under copyright protection of Adolphus Confederate Uniforms, and may not be reproduced without the author's consent. Some of the images are in the public domain and there are no restrictions on their use. Use of other images would require the consent of the museum that furnished them.