The Quintessential Confederate Cap, Part I: Overview of Manufacture, Regulations and Various Designs

Fred Adolphus, 28 April 2023

Updated 27 April 2025

Fred Adolphus, 28 April 2023

Updated 27 April 2025

Introduction

Perhaps no item of the Confederate soldier’s uniform is more iconic than the cap. It certainly ranks alongside the slouch hat with its brim turned up in front, the shell jacket and the bedroll. It was distinctive from its Federal counterpart, having been cut along the lines of the French chasseur kepi. As such, it had a certain rakish appeal that the Yankee cap lacked. One Union soldier described the Northern counterpart as “the unshapely, un-comely forage cap.”[1] So much so, in fact, that the Yankee army adopted their own version of the chasseur kepi in 1872. Despite its French origins Southerners seldom referred to the chasseur style kepi by its French name. That habit was left to reenactors over a hundred years later. Southern soldiers, quartermasters and manufacturers simply called it a cap, and so it will be referred to in this study. Officially, the Confederate Uniform and Dress of the Army regulations prescribed a, “Forage cap…Pattern-Of the form known as the French kepi…” for officers and enlisted men, and refers to it as a “cap,” not a kepi.[2]

Perhaps no item of the Confederate soldier’s uniform is more iconic than the cap. It certainly ranks alongside the slouch hat with its brim turned up in front, the shell jacket and the bedroll. It was distinctive from its Federal counterpart, having been cut along the lines of the French chasseur kepi. As such, it had a certain rakish appeal that the Yankee cap lacked. One Union soldier described the Northern counterpart as “the unshapely, un-comely forage cap.”[1] So much so, in fact, that the Yankee army adopted their own version of the chasseur kepi in 1872. Despite its French origins Southerners seldom referred to the chasseur style kepi by its French name. That habit was left to reenactors over a hundred years later. Southern soldiers, quartermasters and manufacturers simply called it a cap, and so it will be referred to in this study. Officially, the Confederate Uniform and Dress of the Army regulations prescribed a, “Forage cap…Pattern-Of the form known as the French kepi…” for officers and enlisted men, and refers to it as a “cap,” not a kepi.[2]

002a-f: Images from the 1861 and 1862 Confederate Uniform Regulations, The top row depicts the 1861 regulation infantry, artillery and cavalry caps. The bottom row shows the 1862 regulation cavalry, infantry and artillery caps. Images courtesy of Kirk Lyons.

The typical Confederate chasseur kepi’s chief characteristics included the following: the outside cap components are made of a basic cloth. In shape, the body of the cap rose straight up in front some three or three-and-half-inches, while the sides tapered in slightly towards the top. The rear of the cap rose higher than the front at the top, and the back seam sloped forwards in an arc, over the back of the head, from the rear band seam. The body of the cap is made up of two side pieces joined by a front and a rear seam. The top of the cap, for purposes of this study called the “crown,” consisted of a round, stiffened disc of pasteboard with the sides sewed to it in a countersunk fashion. Essentially, the crown was laid with its top upwards, the body turned inside-out with the top edge fastened around the edge of the crown, about a half of an inch inside from the edge, and then pulled down around the crown, right side-out, thus leaving the sides folded over the seams around the edge of the crown. Viewed from the side, the crown slants at a downward angle from rear to front, being higher at the rear seam that at the front seam. The bottom edges of the sides have a band sewn all the way around. The band piece forms the base of the cap with its seam in the rear.

To the front base of the cap body, a visor is added, usually about two inches deep from the front seam to the front edge of the visor. The visor shape is roughly rectangular with rounded corners. The scallop cut out for the forehead, that is sewn to the bottom edge of the front of the cap, is cut deep enough so that it fits the curve of the forehead well enough to prevent the bill from rolling around the wearer’s eyes. The deep scallop is another characteristic that differentiates the Confederate cap from its Union counterpart. A chinstrap is added over the visor culminating on either side just past the ends of the visor, and is secured in place with a small button on either side. Confederate caps usually dispensed with the brass adjustment buckle and relied on to sewn-on keepers to adjust the chinstrap. The cap was usually lined with cotton osnaburg (sides and crown), had a sweatband around the bottom inside edge, and the band was stiffened with buckram, pasteboard or even leather. The visor, chinstrap and sweatband may be made of leather or of enameled cloth. Visors made of pasteboard were protected by enameled cloth layers on top, bottom and around the outer edge with a welt. Regardless, the visor was glazed with shellac or varnish. The chinstrap might be an adjustable, two-piece type, or a non-functional, one-piece type.

Confederate uniform regulations of June 6, 1861 prescribed caps with cadet gray cloth sides and crowns, and with colored bands: red for artillery; light blue for infantry; and, yellow for cavalry. The amended regulations of January 24, 1862 prescribed dark blue caps for general officers, staff officers and engineers, and caps for all others to have dark blue bands with the sides and crown as follows: red for artillery; light blue for infantry; and, yellow for cavalry.[3] In practice, the 1861 pattern cap, gray with a colored band, was made throughout the war. The 1862 pattern cap, with colored sides and crown, and dark blue band, was usually restricted to officer use. The records suggest that manufacturers seldom had enough colorful cloth to make the 1862 cap in mass quantities, but occasionally had enough for the band. As such, the 1861 style cap proved more economical than the 1862, and it continued to be manufactured the entire war. On account of the lack of colored cloth, 1862 pattern caps were quite scarce in the enlisted ranks. In fact, even the 1861 pattern cap yielded largely to the manufacture of a simpler, plain, solid gray cap, which was cheaper to make. The plain gray cap seems to have been the most commonly made variant overall.

In 1861, demand for the military cap was high among individual soldiers and entire companies going off to war. Private manufacturers throughout the South met this demand by supplying chasseur style caps. They charged varying prices, depending on quality and complexity. As the troops took to the field, however, they became less fond of the cap, and preferred wearing soft slouch hats instead, undoubtedly due to the slouch hat’s comfort and practicality. Regarding the cap’s enduring popularity, the artillery most strongly preferred caps, while the infantry liked them to a far lesser degree, and the cavalry seems to have eschewed them almost entirely. Nonetheless, the military cap was firmly entrenched within the framework of the Confederate military, and would be produced, issued and worn in varying degrees throughout the War.

Cap Manufacture

Regarding the manufacture of caps, private sources made them at the start, selling them to either individuals or to local military organizations. As government clothing manufacturing developed, the Confederate quartermaster department fabricated caps alongside private contractor operations. The quartermaster depots cut out sets of materials that were parceled out to local seamstresses who pieced the sets together for a modest wage. Often, private companies manufactured the visors and sold them to the depot. Throughout the cap making business, visor fabrication seems to have formed its own niche, being made either by the government shoe shop or by a firm that specialized in this particular article. Thus, the factory making the caps had itself relied upon another shop to provide it with its visors. By looking at the operations of several depots, one can get a fair idea of how the system worked.

The Houston, Texas clothing depot has left good records of its operations, and this is a good place to start. Captain E.C. Wharton, Chief of the Texas (Confederate) Clothing Bureau, reported specifically on the Houston tailor shop operation in late 1863. The shop had two branches: cutting and issuing. The cutting branch received the material and cut it by pattern into jackets, trousers, shirts, drawers and caps. The Houston uniforms were made chiefly from imported, cadet gray cloth (dark, blue-gray kersey), and Wharton’s records indicate that his caps were made exclusively from this cloth. The caps were manufactured either from the scrap cloth left from cutting out jackets and trousers, or from bulk cloth, at the rate of twelve yards of double width, imported “Cadet Grey Cloth” for 144 caps. The depot’s government shoe shop made the visors. According to Wharton’s description the caps were made with a gray-cloth body [sides and crown]; with red, blue or yellow narrow cloth bands to indicate the service; with bleached domestic or calico for the lining; with flax thread and penitentiary spool cotton thread for sewing; and, with pasteboard for the crown stiffening. A “glaized,” plain leather visor, from the shoe shop, finished the cap components. Wharton mentioned nothing about chinstraps, buttons or sweatbands, but this was probably an oversight. In any case, the cutters would have bundled the components together and turned the bundles over to the issuing branch clerk. The issuing clerk delivered the unfinished clothing bundles to the hundreds of sewing women in Houston who assembled the cut sets into clothing. The issuing clerk subsequently gathered and inspected the finished clothing, paying the sewing women for the garments they completed. In November 1863, Wharton’s bureau paid the sewing women 75 cents for each cap they pieced together. Interestingly, by 1865, the Houston Depot had stopped producing caps altogether, issuing wool hats in their stead.[4]

It is worth noting, that the Houston records indicate that the depot produced caps only in the 1861 regulation pattern with colored bands (in all three branch colors) and never as plain gray caps without branch color. Furthermore, Wharton mentioned in December 1862 and July 1863, that, given the correct materials, he would ideally have manufactured the 1862 regulation cap. He compiled requirements for cap materials based on the 1862 regulations, listing dark blue cloth for bands, and red, yellow and light blue cloth for the crowns and sides. His requirements also called for small metal buttons, glazed leather chinstraps and visors, white cambric or white linen linings, and oil silk cap covers.[5] Wharton was never able to implement the 1862 style cap due to the shortage of colored cloth, so he made the 1861 style cap which required less colored trim cloth. The Houston, 1861 style cap reflected the general state of affairs in Confederate cap manufacture, offers a plausible explanation for why so few 1862 regulation caps were made, and explains why so many 1861 regulation caps, or plain caps without colored bands were made throughout the South.

While the study of the Houston Depot cap gives a good general picture of Confederate cap manufacture, it does not provide specifics about the caps made in Virginia or Lower South. For this we must rely on the sketchier records of Virginia, Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. In lieu of manufacturing records, we can often examine the products of various factory operations to determine what was made and how. Perhaps a good place to begin the study of the Confederate cap is with some originals that embody the intent of the Confederate uniform regulations from 1861 and 1862, as well as common variants.

Confederate Uniform Regulation 1861 and 1862 Caps

Three caps with provenance to the Army of Northern Virginia follow the uniform regulations fairly closely. These include Captain R.H. Alexander’s enlisted pattern 1861 cap; an unidentified 1861 artillery cap; and, Corporal Anthony S. Barksdale’s 1862 artillery cap.

Captain Robert H. Alexander served as a quartermaster officer for the 30th Virginia Infantry. He presumably obtained his 1861-pattern, enlisted-style cap in 1863. The cadet-gray kersey cap has a black woolen band, instead of a blue, infantry-color band. The black band reflects the prolific use of this color for trimming Confederate uniforms. Even though black was not an official branch-of-service color, it served as a viable substitute for official colors since it was readily available throughout the South. The visor is a high-quality leather, composition type with a leather welt. (A composition visor was made in two, thin layers, with the hair side visible, top and bottom; glued together and sewn together around the outer edge). The sweatband is likewise leather with a raw edge at the base. The sweatband is of a heavier weight than most, but not significantly so. No stiffener was visible under the sweatband, however, the interior sides and crown are lined with enameled cloth. The lining is made of unbleached, tan-colored osnaburg, perhaps nankeen cotton, in the bag style seen in some Richmond Depot caps. The chinstrap and buttons are missing.

In 1861, demand for the military cap was high among individual soldiers and entire companies going off to war. Private manufacturers throughout the South met this demand by supplying chasseur style caps. They charged varying prices, depending on quality and complexity. As the troops took to the field, however, they became less fond of the cap, and preferred wearing soft slouch hats instead, undoubtedly due to the slouch hat’s comfort and practicality. Regarding the cap’s enduring popularity, the artillery most strongly preferred caps, while the infantry liked them to a far lesser degree, and the cavalry seems to have eschewed them almost entirely. Nonetheless, the military cap was firmly entrenched within the framework of the Confederate military, and would be produced, issued and worn in varying degrees throughout the War.

Cap Manufacture

Regarding the manufacture of caps, private sources made them at the start, selling them to either individuals or to local military organizations. As government clothing manufacturing developed, the Confederate quartermaster department fabricated caps alongside private contractor operations. The quartermaster depots cut out sets of materials that were parceled out to local seamstresses who pieced the sets together for a modest wage. Often, private companies manufactured the visors and sold them to the depot. Throughout the cap making business, visor fabrication seems to have formed its own niche, being made either by the government shoe shop or by a firm that specialized in this particular article. Thus, the factory making the caps had itself relied upon another shop to provide it with its visors. By looking at the operations of several depots, one can get a fair idea of how the system worked.

The Houston, Texas clothing depot has left good records of its operations, and this is a good place to start. Captain E.C. Wharton, Chief of the Texas (Confederate) Clothing Bureau, reported specifically on the Houston tailor shop operation in late 1863. The shop had two branches: cutting and issuing. The cutting branch received the material and cut it by pattern into jackets, trousers, shirts, drawers and caps. The Houston uniforms were made chiefly from imported, cadet gray cloth (dark, blue-gray kersey), and Wharton’s records indicate that his caps were made exclusively from this cloth. The caps were manufactured either from the scrap cloth left from cutting out jackets and trousers, or from bulk cloth, at the rate of twelve yards of double width, imported “Cadet Grey Cloth” for 144 caps. The depot’s government shoe shop made the visors. According to Wharton’s description the caps were made with a gray-cloth body [sides and crown]; with red, blue or yellow narrow cloth bands to indicate the service; with bleached domestic or calico for the lining; with flax thread and penitentiary spool cotton thread for sewing; and, with pasteboard for the crown stiffening. A “glaized,” plain leather visor, from the shoe shop, finished the cap components. Wharton mentioned nothing about chinstraps, buttons or sweatbands, but this was probably an oversight. In any case, the cutters would have bundled the components together and turned the bundles over to the issuing branch clerk. The issuing clerk delivered the unfinished clothing bundles to the hundreds of sewing women in Houston who assembled the cut sets into clothing. The issuing clerk subsequently gathered and inspected the finished clothing, paying the sewing women for the garments they completed. In November 1863, Wharton’s bureau paid the sewing women 75 cents for each cap they pieced together. Interestingly, by 1865, the Houston Depot had stopped producing caps altogether, issuing wool hats in their stead.[4]

It is worth noting, that the Houston records indicate that the depot produced caps only in the 1861 regulation pattern with colored bands (in all three branch colors) and never as plain gray caps without branch color. Furthermore, Wharton mentioned in December 1862 and July 1863, that, given the correct materials, he would ideally have manufactured the 1862 regulation cap. He compiled requirements for cap materials based on the 1862 regulations, listing dark blue cloth for bands, and red, yellow and light blue cloth for the crowns and sides. His requirements also called for small metal buttons, glazed leather chinstraps and visors, white cambric or white linen linings, and oil silk cap covers.[5] Wharton was never able to implement the 1862 style cap due to the shortage of colored cloth, so he made the 1861 style cap which required less colored trim cloth. The Houston, 1861 style cap reflected the general state of affairs in Confederate cap manufacture, offers a plausible explanation for why so few 1862 regulation caps were made, and explains why so many 1861 regulation caps, or plain caps without colored bands were made throughout the South.

While the study of the Houston Depot cap gives a good general picture of Confederate cap manufacture, it does not provide specifics about the caps made in Virginia or Lower South. For this we must rely on the sketchier records of Virginia, Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. In lieu of manufacturing records, we can often examine the products of various factory operations to determine what was made and how. Perhaps a good place to begin the study of the Confederate cap is with some originals that embody the intent of the Confederate uniform regulations from 1861 and 1862, as well as common variants.

Confederate Uniform Regulation 1861 and 1862 Caps

Three caps with provenance to the Army of Northern Virginia follow the uniform regulations fairly closely. These include Captain R.H. Alexander’s enlisted pattern 1861 cap; an unidentified 1861 artillery cap; and, Corporal Anthony S. Barksdale’s 1862 artillery cap.

Captain Robert H. Alexander served as a quartermaster officer for the 30th Virginia Infantry. He presumably obtained his 1861-pattern, enlisted-style cap in 1863. The cadet-gray kersey cap has a black woolen band, instead of a blue, infantry-color band. The black band reflects the prolific use of this color for trimming Confederate uniforms. Even though black was not an official branch-of-service color, it served as a viable substitute for official colors since it was readily available throughout the South. The visor is a high-quality leather, composition type with a leather welt. (A composition visor was made in two, thin layers, with the hair side visible, top and bottom; glued together and sewn together around the outer edge). The sweatband is likewise leather with a raw edge at the base. The sweatband is of a heavier weight than most, but not significantly so. No stiffener was visible under the sweatband, however, the interior sides and crown are lined with enameled cloth. The lining is made of unbleached, tan-colored osnaburg, perhaps nankeen cotton, in the bag style seen in some Richmond Depot caps. The chinstrap and buttons are missing.

Another example of an 1861 artillery cap is a souvenir picked up by a New York soldier in Virginia. It has no further provenance, but was probably worn by an Army of Northern Virginia artilleryman. The chasseur cap has a cadet gray, satinet body (sides and crown), with a red flannel band. The visor is composition leather with a welt, and the chinstrap and buttons are missing. The lining and sweatband have not been observed.

Corporal Anthony S. Barksdale’s artillery cap provides an example of an enlisted, 1862 pattern cap. Barksdale served with the 1st Battalion, Virginia Light Artillery in the Army of Northern Virginia. He wore this cap during 1864-65. The cap has a navy-blue, satinet band and red, satinet sides and crown. The composition visor has a top and bottom layer of enameled cloth with a pasteboard, or perhaps leather layer, in between. The machine-stitched edge lacks a welt, but the exposed, edge of the layers have been coated with enamel. The two-piece, enameled cloth chinstrap is secured with Federal, general service buttons. The lining and sweatband are missing, but this exposes the buckram interlining, which extends all the way from the base to the crown, and the inside of the crown. The inside of the crown is covered with a light weight, pale blue-colored cotton fabric. While Barksdale’s cap appears to be a depot-made cap, it does not conform to the construction of the Richmond cap. Perhaps it represents a small scale, manufacturing run made especially for Lee’s artillery battalions.[6]

While the 1861 pattern cap continued to be manufactured throughout the war for enlisted troops, despite having been officially superseded, the 1862 never saw large scale, quartermaster production. The 1862 pattern cap did see widespread usage as an officer cap, it being the most popular officer cap of the war. By contrast, officers seem to have eschewed the 1861 pattern cap, and few originals of this type survive to present day, reflecting its lack of popularity amongst officers.

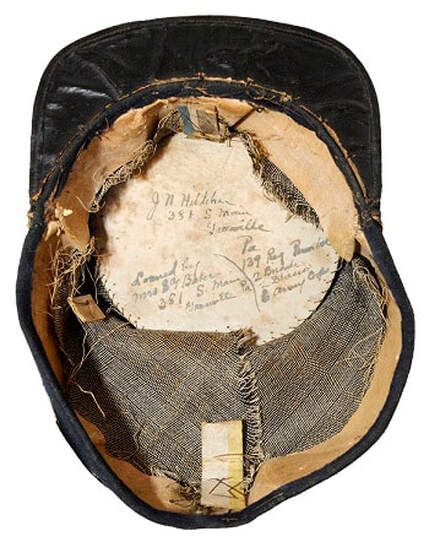

To illustrate the prevalence of the 1862-pattern officer cap, some examples are offered. All have provenance to their Confederate owners. Remarkably, the artillery cap appears to have been made by the same maker that made a similar infantry officer cap. This unprovenanced cap had been taken as a souvenir by a Federal soldier, Private J.W. Hildebran [James W. Hildebrand], Co A, 139th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers. Hildebran’s regiment fought in Northern Virginia, suggesting that he got the cap from an officer in the Army of Northern Virginia, possibly with a South Carolinian provenance.[7]

To illustrate the prevalence of the 1862-pattern officer cap, some examples are offered. All have provenance to their Confederate owners. Remarkably, the artillery cap appears to have been made by the same maker that made a similar infantry officer cap. This unprovenanced cap had been taken as a souvenir by a Federal soldier, Private J.W. Hildebran [James W. Hildebrand], Co A, 139th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers. Hildebran’s regiment fought in Northern Virginia, suggesting that he got the cap from an officer in the Army of Northern Virginia, possibly with a South Carolinian provenance.[7]

010a: This image shows the infantry officer cap taken as a souvenir by Pennsylvania soldier, James W. Hildebrand during the war. The Hildebrand souvenir cap exhibits the regulation dark blue band and Confederate light blue sides and crown that were made from imported fabric. Image and artifact courtesy of the Dr. Michael R. Cunningham collection.

010c: The interior of the Hildebrand cap is especially noteworthy. It appears to be identical to that of Captain William Pratt Parks' artillery cap. The similarity suggests that both the Parks and the Hildebrand caps were made by the same cap maker in South Carolina. Equally noteworthy is that Hildebrand meticulously annotated his biographical information on the inside of the crown. Image and artifact courtesy of the Dr. Michael R. Cunningham collection.

Another variant of the 1861 and 1862 regulation caps harkens back to the design of the 1851 pattern, US army shako. The shako had a colored band at the base that tapered upwards in the front to a point. Some of the early war caps incorporated this pointed-front band, as well. One of the most famous images of Southerners wearing this type of cap are the Virginia militia on guard duty at John Brown’s hanging, December 2, 1859. Incidentally, the pattern 1851 shako was also the basis, and inspiration for the US Army’s pattern 1858 forage cap.

M1858 Style Forage Caps

While the usual Confederate cap was patterned along the lines of the French chasseur kepi, the US army forage cap of 1858 informed the tailoring of some early war, mustering-in caps, as well as some depot operations. A good example of this is hunter green, forage cap believed to have provenance to the Clinch Rifles (later, Company A, 5th Georgia Infantry). The Clinch Rifles forage cap follows the pattern of the 1858 US cap very closely, except that it is made of dark, hunter green cloth. The lightweight, black leather sweatband is folded at the base around the visor and left raw-edged around the rest of the base. The entire cap appears to have buckram interlining all the way up the sides. Differences are minor, such as the green cap’s high-quality, bound leather, composition visor, and the non-military, floral button. The one feature that ties this cap to the Clinch Rifles is the silver bullion, embroidered badge that features the letters “CR” enclosed in a wreath. The dimensions of the wreath are 1 7/8” wide by 1 3/8” high, and the letters are between 3/8” and ½” high and wide. A more definitive provenance may provide a stronger connection to the Georgia Clinch Rifles, but in any case, the cap is an impeccable example of a wartime copy of the 1858 Federal forage cap.[8]

While the usual Confederate cap was patterned along the lines of the French chasseur kepi, the US army forage cap of 1858 informed the tailoring of some early war, mustering-in caps, as well as some depot operations. A good example of this is hunter green, forage cap believed to have provenance to the Clinch Rifles (later, Company A, 5th Georgia Infantry). The Clinch Rifles forage cap follows the pattern of the 1858 US cap very closely, except that it is made of dark, hunter green cloth. The lightweight, black leather sweatband is folded at the base around the visor and left raw-edged around the rest of the base. The entire cap appears to have buckram interlining all the way up the sides. Differences are minor, such as the green cap’s high-quality, bound leather, composition visor, and the non-military, floral button. The one feature that ties this cap to the Clinch Rifles is the silver bullion, embroidered badge that features the letters “CR” enclosed in a wreath. The dimensions of the wreath are 1 7/8” wide by 1 3/8” high, and the letters are between 3/8” and ½” high and wide. A more definitive provenance may provide a stronger connection to the Georgia Clinch Rifles, but in any case, the cap is an impeccable example of a wartime copy of the 1858 Federal forage cap.[8]

The State of North Carolina also patterned its enlisted, quartermaster headgear after the 1858 forage cap, but apparently manufactured the chasseur style cap as well. Numerous images document North Carolina’s prolific use of the forage cap. North Carolina manufacturers sold 38,186 caps to the State of North Carolina quartermaster, and 2,504 caps to the Confederate government at Richmond, Virginia from May 1861 to September 1864. The numerous North Carolina cap makers described their caps as simply caps, or as “Fatigue Caps,” “Army Caps,” “Military Caps,” “Grey Caps,” “Grey Fatigue Caps,” “Light Grey Fatigue Caps,” “Blue Fatigue Caps,” “Red Band Fatigue Caps,” and “Black Band Fatigue Caps.” Brass figures and letters were also in 1861. The North Carolina cloth manufacturing company, Young, Wriston & Orr, left descriptions of their fabrics and colors, which provides an insight into what may have been used to make many of these caps. The Young, Wriston & Orr fabrics from Maythrough August 1861 included “Steel mix Cass,” [steel gray cassimere]; “Cadet Cass,” [cadet gray cassimere]; “Steel mix Janes,” [steel gray jeans]; “Cadet Janes,” [cadet gray jeans]; and, “Cadet Flannel,” [cadet gray]. How many of the North Carolina caps were made in the forage cap pattern is a matter for speculation, but the forage type cap was made at least through 1863. Two originals survive: a black one with provenance to the early war, and a faded tan, cassimere cap that was worn at Gettysburg.

The black cap’s construction closely mirrors that of the Federal cap. The manufacturer omitted the welt beneath crown. As a further simplification over its Federal counterpart, he made the body of the cap from of a single piece of basic cloth (normally made of two separate side pieces) with the seam in the rear. Likewise, the body lining is of one-piece construction with a rear seam. The basic cloth is black satinet with a light brown cotton warp. The lining is unbleached osnaburg. The visor is made of leather composed of two layers machine-stitched together without a welt. The two-piece, leather chinstrap is held in place with four-hole, brown wooden, trouser buttons. The inside crown has a maker’s label that reads, “Manufactured by Wm. P. Denny, High Point, N.C., size [space for hand-written size], price [space for hand-written price].” The enameled cloth sweatband is interesting because it appears to have been cut from an enameled oil cloth carpet, having a painted yellow and red motif. The only available provenance is that one of the six sons of the Lattimore family of Cleveland County, North Carolina wore the cap. Lattimore soldiers from Cleveland County who enlisted early in 1861 served in the 15th, 34th and 49th North Carolina Infantry Regiments. Assuming that the maker’s label is genuine, the cap was made for the State of North Carolina by William P. Denny. Cap maker Denny delivered 470 caps to the North Carolina State Quartermaster between 25 January and 6 March, 1862, at $1.25 each, so this black forage cap may have been part of that contract.[9]

The black cap’s construction closely mirrors that of the Federal cap. The manufacturer omitted the welt beneath crown. As a further simplification over its Federal counterpart, he made the body of the cap from of a single piece of basic cloth (normally made of two separate side pieces) with the seam in the rear. Likewise, the body lining is of one-piece construction with a rear seam. The basic cloth is black satinet with a light brown cotton warp. The lining is unbleached osnaburg. The visor is made of leather composed of two layers machine-stitched together without a welt. The two-piece, leather chinstrap is held in place with four-hole, brown wooden, trouser buttons. The inside crown has a maker’s label that reads, “Manufactured by Wm. P. Denny, High Point, N.C., size [space for hand-written size], price [space for hand-written price].” The enameled cloth sweatband is interesting because it appears to have been cut from an enameled oil cloth carpet, having a painted yellow and red motif. The only available provenance is that one of the six sons of the Lattimore family of Cleveland County, North Carolina wore the cap. Lattimore soldiers from Cleveland County who enlisted early in 1861 served in the 15th, 34th and 49th North Carolina Infantry Regiments. Assuming that the maker’s label is genuine, the cap was made for the State of North Carolina by William P. Denny. Cap maker Denny delivered 470 caps to the North Carolina State Quartermaster between 25 January and 6 March, 1862, at $1.25 each, so this black forage cap may have been part of that contract.[9]

The tan-colored, North Carolina forage cap was worn by Amzi Leroy Williamson, Company B, 53rd North Carolina Troops, at the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1863. The cap’s basic cloth would have been steel- or cadet gray before it faded to tan. Williamson’s cap resembles both the Federal, 1858 forage cap, and the Latimer cap, in its overall appearance. However, there are significant differences in tailoring between the Latimer and Williamson caps. The sides of the Williamson cap are of two-piece construction; the cap has a separate, two-piece band; and, the crown has a retaining welt around the edge. The crown welt seam is positioned in the front left. Furthermore, the visor is plain leather, made from a single piece. Williamson marked the underside of the visor, “ALW 1863.” The chinstrap and buttons are missing. The lining is intact, and is made from a brown and tan, floral-print, cotton fabric. The cap has no sweatband and appears not to have ever had one. The cap is part of a collection that includes Williamson’s jacket and a cased portrait image. The accompanying portrait shows Williamson wearing the cap and jacket.[10]

Caption:

Caption:

Two Confederate forage caps, quite similar to one another, that have features of both the Union, 1858-pattern forage cap, and the Confederate chasseur cap, are the Sweatman and Perkins caps. Both have the general shape of the Union cap, along with the crown welt. The visor, however, follows the usual Confederate form, cut with a deep scallop, sewn to the front edge, and made to stick out flat.

The forage cap worn by Private R.V. Sweatman, from 1864 to 1865, has provenance to the Charleston area. Sweatman served in Kannapaux’s South Carolina Artillery Battalion on the South Carolina coast. The cap’s basic cloth is tannish-gray jeans that has probably faded from steel gray or cadet gray. The lining is unbleached osnaburg, the sweatband enameled cloth, and the visor is leather. The chinstrap and buttons are missing. The body of the cap follows the shape of the Federal forage cap, but it has a separate, one-piece band. The band’s seam closes in the front rather that at the rear of the cap. The crown is held in place with a reinforced welt placed between it and the side pieces, the welt’s reed stiffener acting as a spring to hold the welt’s circular shape and prevent the crown from collapsing into the sides. The welt is made of red cloth, a feature that dates to the ante-bellum, 1858 pattern, Federal forage cap, when these caps were trimmed with their branch-of-service color. Other than the red crown welt, the band is trimmed with a piece of three-quarter inch wide, red woolen tape. The tape is sewn into the top edge of the band and does not extend to the base (only a half inch of the tape extends from the seam).[11]

The forage cap worn by Private R.V. Sweatman, from 1864 to 1865, has provenance to the Charleston area. Sweatman served in Kannapaux’s South Carolina Artillery Battalion on the South Carolina coast. The cap’s basic cloth is tannish-gray jeans that has probably faded from steel gray or cadet gray. The lining is unbleached osnaburg, the sweatband enameled cloth, and the visor is leather. The chinstrap and buttons are missing. The body of the cap follows the shape of the Federal forage cap, but it has a separate, one-piece band. The band’s seam closes in the front rather that at the rear of the cap. The crown is held in place with a reinforced welt placed between it and the side pieces, the welt’s reed stiffener acting as a spring to hold the welt’s circular shape and prevent the crown from collapsing into the sides. The welt is made of red cloth, a feature that dates to the ante-bellum, 1858 pattern, Federal forage cap, when these caps were trimmed with their branch-of-service color. Other than the red crown welt, the band is trimmed with a piece of three-quarter inch wide, red woolen tape. The tape is sewn into the top edge of the band and does not extend to the base (only a half inch of the tape extends from the seam).[11]

The other forage cap matching Sweatman’s belonged to Private Stephen Joseph Perkins, Company H, 2nd Virginia Fluvanna Artillery. Perkins served in the Army of Northern Virginia at least from February 1862 until his capture at Louisa Court House on 12 March 1865. According to family lore, Perkins wore his cap during the Shenandoah Valley campaign of 1862 and at the Battle of Gettysburg. After Gettysburg, he is said to have gifted the cap to his sister-in-law, Judith, because it offered little protection from the elements and he no longer wished to wear it. His sister-in-law hanged the cap on a peg at her home, where it remained for over a hundred years. Accordingly to family history, the basic fabric was made from “homespun wool and dyed with chestnut shells.” The cap’s visor is missing and probably fell off as the cap hanged from the peg over such a long period. The visor pictured with the cap was added for the museum exhibit.

The cap would appear to have been made may a professional tailor, probably as part of an early-war consignment for caps to Perkin’s company. The basic cloth is steel gray jeans. The sides are two-piece construction without a separate band piece, similar to the construction of the Federal army forage cap. The front height of the cap is 5 ⅝ inches.

The crown is 5 ½ inches in diameter, and is supported with a prominent welt. The crown welt is made of red woolen flannel, stiffened with a ⅛ inch thick, twisted, white cotton cord. The crown is embellished with a crossed cannon badge (1 ¼ inches high and 1 ¾ inches wide); a one-half inch high, brass letter “H” positioned in the lower part of the cannon; and, a ⅜ inch high, brass letter “A” positioned just above the cannon. Due to the off-set positioning of the “A,” it is likely that the crown had one or two additional letters that are now missing (possibly an “F” and a “V” for “Fluvanna” and “Virginia”).

The one-piece band trimming around the base of the cap is of 1 ¼ inch wide, red woolen tape. The trim tape was applied to base about a quarter inch above the bottom edge, and is seam is placed at the front of the cap rather than at the rear.

The cap’s chinstrap is missing, but its buttons remain intact. These are ⅝ inch, cap-size buttons, with the Virginia seal on the face.

The sweatband is of the highest quality: red-dyed leather, 1 ⅛ inches wide. The unbleached, osnaburg lining is made in the “bag” style without a separate crown. The top of the bag has a draw string that tightens to close the bag to a narrow opening. [12]

The cap would appear to have been made may a professional tailor, probably as part of an early-war consignment for caps to Perkin’s company. The basic cloth is steel gray jeans. The sides are two-piece construction without a separate band piece, similar to the construction of the Federal army forage cap. The front height of the cap is 5 ⅝ inches.

The crown is 5 ½ inches in diameter, and is supported with a prominent welt. The crown welt is made of red woolen flannel, stiffened with a ⅛ inch thick, twisted, white cotton cord. The crown is embellished with a crossed cannon badge (1 ¼ inches high and 1 ¾ inches wide); a one-half inch high, brass letter “H” positioned in the lower part of the cannon; and, a ⅜ inch high, brass letter “A” positioned just above the cannon. Due to the off-set positioning of the “A,” it is likely that the crown had one or two additional letters that are now missing (possibly an “F” and a “V” for “Fluvanna” and “Virginia”).

The one-piece band trimming around the base of the cap is of 1 ¼ inch wide, red woolen tape. The trim tape was applied to base about a quarter inch above the bottom edge, and is seam is placed at the front of the cap rather than at the rear.

The cap’s chinstrap is missing, but its buttons remain intact. These are ⅝ inch, cap-size buttons, with the Virginia seal on the face.

The sweatband is of the highest quality: red-dyed leather, 1 ⅛ inches wide. The unbleached, osnaburg lining is made in the “bag” style without a separate crown. The top of the bag has a draw string that tightens to close the bag to a narrow opening. [12]

018o: A Confederate sergeant wears a forage cap with a dark band (cropped and magnified at the right). This cap is similar to Sweatman and Perkins caps. Image courtesy of Civil War Times Illustrated, back cover, October 1977, James C. Frasca collection.

Yet more Southern caps take their inspiration from the US army, 1858 pattern forage cap. One of the well-known variants is the “Stonewall Jackson” style cap, so named herein since this cap is closely associated with the famous general. This style improved on the standard 1858 cap’s appearance by increasing the overall height, adding a larger crown and usually substituting a crescent visor for the rectangular model, more reminiscent of the Mexican War type. The added height allowed the crown to tilt forward, in contrast to the regulation forage cap where the body of the cap stood straight up with a crumpled appearance. The larger crown was handsomer and its forward tilt made possible a show of flashy, brass insignia. The crescent visor was cut with a very shallow scallop that forced the visor to bend around the wearer’s forehead and arch downwards over his brow. Early in the war, numerous volunteer companies wore this style cap, but surprisingly, later in the war, an unknown manufacturer in Virginia apparently began making a simplified version of this cap in imported, dark, cadet gray kersey, judging from surviving originals. The chief difference in cut between the early- and late-war Stonewall caps is the height. The early-war caps were made with higher sides that allowed the crown to tilt further forward. The late-war variant had slightly lower sides that kept the crown from tilting forward quite as much. In any case, it appears that the late-war variant was worn almost exclusively by officers, with half the extant caps having gold lace. Those without gold lace might also be worn by officers, or by enlisted soldiers who managed to acquire one. These caps were occasionally made with rectangular visors.

Starting with the obvious enlisted Stonewall caps, that of Kennedy Palmer, Company H, 13th Virginia Infantry, is the earliest. Palmer presumably obtained this cap with his mustering-in uniform in 1861, and wore it during the first part of his service. Palmer’s cap has a variegated color scheme: a light gray band and crown with dark blue sides. The sides are very high, allowing the front to flop forward on top of the visor. The seams are edged with red welts between the band, side and crown seams. It has the hallmark crescent-shaped, bound, leather visor, and a two-piece leather chinstrap with Virginia buttons. The crown is ornamented with brass fittings that show Palmer’s affiliation: 13 Va co H.[13]

Another early-war Stonewall cap, that resides in the Washington and Lee University collection, is attributed to a soldier of Company L, 4th Virginia Infantry (as only the 4th Infantry had a Company L). It is otherwise unidentified, but was probably worn with a mustering-in uniform in 1861. The cap is dark blue in color with very high sides; it has a two-piece leather chinstrap secured with brass, floral-motif buttons; and, has a crescent-shaped, leather visor. The base of the cap appears to have an inch-wide band of gold braid attached. The crown is adorned with brass insignia that provides its provenance: L 4 VA.[14]

Another early-war Stonewall cap, that resides in the Washington and Lee University collection, is attributed to a soldier of Company L, 4th Virginia Infantry (as only the 4th Infantry had a Company L). It is otherwise unidentified, but was probably worn with a mustering-in uniform in 1861. The cap is dark blue in color with very high sides; it has a two-piece leather chinstrap secured with brass, floral-motif buttons; and, has a crescent-shaped, leather visor. The base of the cap appears to have an inch-wide band of gold braid attached. The crown is adorned with brass insignia that provides its provenance: L 4 VA.[14]

The next cap has characteristics associated with regular wartime production, and offers evidence of a type made for both soldiers and officers. This cap is made from imported, dark blue-gray kersey: a cloth normally associated with the time-period of the spring of 1863 to the end of the war, in the Army of Northern Virginia. Lemuel H. Williams, served in Company G, 9th Virginia Infantry between 10 May 1862 to 3 July 1863 (when he was killed at Gettysburg). Given that the basic fabric was probably not available until about May 1863, it is likely that Williams only wore the cap in the weeks preceding his death. The cap is missing its chinstrap, buttons and visor. It has the high sides associated with the Stonewall typology, but not as high as the early-war caps. With a front height of five inches, the crown cannot tilt all the way forward. The cap has a lightweight, leather sweatband with a raw edge at the base. The leather has a peculiar, dark striped pattern printed on its surface. The lining is a cotton, floral print.[15]

The next two caps made in an enlisted style were purportedly worn by officers. That being the case, these caps may have been intended for enlisted soldiers, but were acquired and used by officers without further embellishment, as was often the case with other enlisted caps. Both caps closely mirror Lemuel H. Williams’ cap, being made from imported, dark, blue-gray kersey, and having the same basic cut with high sides. Both of these caps retain their crescent-shaped, leather visors. One, attributed to Captain Will Hardin, 47th Georgia Infantry, still has its two-piece leather chinstrap, with a single ordnance button (Tice ORD200). Hardin’s cap has an enameled cloth sweatband and a tan-colored, polished cotton lining. Hardin’s Confederate service records are inconclusive.[16] The other cap, attributed to Captain Robert H. Alexander, Company C, 30th Virginia Infantry, is missing its chinstrap and buttons. Unfortunately, at this time, a picture of this cap is not available, but it is pictured in Echoes of Glory: Confederacy on page 165. The artifact's provenance is sketchy.[17] While both caps appear to be authentic, their provenance is unknown.

If we are to consider the cadet gray, wartime Stonewall cap as a commonly produced style, we have to turn to the surviving officer caps for the bulk of the evidence. As mentioned, most of this type seems to have been used predominately by officers. Perhaps General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s cap did inspire, to some degree, a widespread usage among Southern officers. In any case, it bears mentioning Stonewall Jackson’s two, famous forage caps. Jackson’s first cap was part of his Virginia Military Institute professor’s uniform. He wore this cap until the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. This cap is made of black woolen cloth. It has the crescent-shaped, composition leather visor, with a stitched edge, that is commonly associated with the type. It has very high sides that allow to crown to easily tilt forward to the visor. Its two-piece leather chinstrap is secured with floral-motif, brass buttons. No images are available of the inside.[18] Jackson’s second cap was made of gray cloth that has since faded to tan. The second cap is nearly identical in cut to the first, and Jackson wore the cap from the Battle of Fredericksburg until death in May 1863. A band of black cloth was added to the base of the cap, just above the edge. Over this band, another band of half-inch gold braid was added. The cap has the usual crescent-shaped, bound-leather visor and very high sides. The two-piece leather chinstrap is intact, but one of the buttons is missing. An image of the inside is not available.[19]

The first of the caps with late-war characteristics is that of Captain Obediah Jennings Wise, 46th Virginia Infantry, who was killed wearing his cap at Roanoke Island, in early 1862. Wise’s cap has dark, blue-gray satinet sides and crown. A separate black band was added to the cap, slightly above the base, with a gold braid strand at the bottom. Another gold braid strand is added to the crown welt. There is an embroidered bouillon badge on crown. The two-piece leather chinstrap is intact, along with one Virginia button. The characteristic, crescent-shaped, leather visor has become detached from the front. No image of the inside is available. This cap marks the change in pattern to slightly lower sides, whereby the crown cannot fall fully forward to the visor, as was the case with many earlier Stonewall caps. It is also worth noting that the gold braid is minimal.[20]

The next of these caps was worn by a Captain Wallace, of Gordonsville, Virginia. The provenance for this cap is sparse, to include Wallace's service records. Assuming that the cap survived because it was the last that Wallace wore during the war, and judging from the imported fabric, we might infer the cap dates to 1864-65. His cap has some notable characteristics of the late-war Stonewall cap. It is made from dark, blue-gray kersey. The sides are high, but not so high as to allow the crown to fall fully forward, the front height being 4 1/8 inches. It has a rectangular, bound-leather visor, and a two-piece leather chinstrap held by a single, remaining Virginia button. The cap has two strands of gold braid on the sides and base, and one on the crown. The cap is lined with black, polished cotton lining. The sweatband is missing and there is buckram around the base.[21]

026i: The cap's damage affords a clear view of the interior construction and components. The base was reinforced with a band of buckram. The sides were stiffened with a layer of cotton batting. The lining is made from polished cotton fabric. Interestingly, the crown appears to have no pasteboard stiffening. The crown has been stiffened solely by the tension offered by the reed-reinforced crown welt. The high-quality leather visor is made with hair-side components, both top and bottom, and secured with a leather welt around the outer edge.

Moving to a cap with very strong provenance, we come to Colonel George Wythe Randolph. Randolph served with the 1st Virginia Artillery that re-designated in 1864 as the 1st Battalion, Virginia Light Artillery. Assuming that this was the last cap that Randolph wore during his service, he would have worn it in 1864-65. His cap embodies all of the chief characteristics of the late-war Stonewall cap: it is made from dark, blue-gray kersey; it has a crescent-shaped, bound-leather visor; and, it has moderately high sides (the 4 ¼ inch high front allows the crown to only slightly fall forward). The cap retains its two-piece leather chinstrap held on with Federal, general service buttons. The gold braid is set at four strands around the base, two for the sides and one on the crown. The inside of the cap has a lightweight, black leather sweatband that has a raw edge all around the base. The lining is black, polished cotton with buckram stiffening around the base.[22]

The next cap with all the characteristic hallmarks of the late-war Stonewall cap was supposedly worn by Captain George R. Gaither. Gaither’s service records indicate that he served with Company K, 1st Virginia Cavalry and Company K, 1st Battalion Maryland Cavalry from 1861 to October 1863. He resigned due to a disability with hemorrhoids, a condition that would have precluded strenuous riding. So, Gaither would have worn the cap in 1863. This provenance is tenuous, however, because the collector who sold the cap reported the Confederate owner’s name and regiment as “Gaiuthier, 10th Virginia Cavalry,” for which there is no service record. In any case, the cap was made from dark, blue-gray kersey; has a crescent-shaped, bound-leather visor; and high sides that allow the crown to tilt slightly forward. The cap retains the two-piece leather chinstrap with its Virginia buttons. The cap has gold braid with two strands around the base and on the sides, and one strand on the crown. No image is available for the inside.[23]

The last example of this cap has all the characteristics associated with the type: blue-gray kersey basic cloth; crescent-shaped, bound-leather visor; and, high sides. There are three rows gold braid around the base, two strands on the sides, and one on the crown. The chinstrap and buttons are missing. The inside has a very wide, russet leather sweatband that is folded inwards along the visor and left raw around the rest of the base. The black, polished cotton lining is secured to the crown. Unfortunately, this unidentified cap is without provenance.[24]

The last variant of the forage cap to be mentioned herein is a hybrid between the 1858 pattern and the common Confederate chasseur cap. This style has the base and sides of the chasseur cap, but the crown is attached in the manner of the 1858 pattern cap. The crown lacks the chasseur’s countersinking, and has a welt around the base of the crown to hold it in place. The diameter of the crown is comparable to those of regular, Confederate chasseur cap, and the overall height and shape, front to rear, matches those of the typical chasseur, as well. There are at least two surviving examples of this cap, as well as some contemporary images of soldiers wearing this style cap. Noted uniform historian, Dr. Michael R. Cunningham, has dubbed this style the “hybrid forage cap” as it incorporates features of both the chasseur cap and the Federal forage cap.

The first of the surviving caps is without provenance. The basic cloth of the sides and crown is a light steel-gray colored twill with a very heavy nap that easily conceals the warp. The weave’s weft goes over two and under two warp yarns and the warp goes over one and under two weft yarns. The thick weft yarn is light gray and heavy, coarse a warp yarn is a natural white. The band is a lightweight, black woolen flannel. The leather composition visor is made from two layers of very thin leather that have been glued together and machine-sewn around the outer edge without a welt. The two-piece leather chinstrap is intact, but a segment is missing from the left-side component. The right-side component is complete, to include its leather keeper. The sweatband is enameled cloth and the lining a fine white, polished cotton. The band appears to be stiffened with pasteboard or leather, and the chinstrap is secured with four-hole, white bone buttons.[25].

The first of the surviving caps is without provenance. The basic cloth of the sides and crown is a light steel-gray colored twill with a very heavy nap that easily conceals the warp. The weave’s weft goes over two and under two warp yarns and the warp goes over one and under two weft yarns. The thick weft yarn is light gray and heavy, coarse a warp yarn is a natural white. The band is a lightweight, black woolen flannel. The leather composition visor is made from two layers of very thin leather that have been glued together and machine-sewn around the outer edge without a welt. The two-piece leather chinstrap is intact, but a segment is missing from the left-side component. The right-side component is complete, to include its leather keeper. The sweatband is enameled cloth and the lining a fine white, polished cotton. The band appears to be stiffened with pasteboard or leather, and the chinstrap is secured with four-hole, white bone buttons.[25].

The other hybrid forage cap is in the Gettysburg National Park collection. Its provenance asserts that it was picked up off the battlefield as a souvenir in 1863. The images of this cap (courtesy of Dr. Michael R. Cunningham) indicate that it conforms closely to Cunningham’s cap. The basic cloth of the sides and crown is a light sheep’s gray cloth, perhaps satinet. The band appears to have been black (now faded). The one-piece leather visor and enameled cloth, two-piece chinstrap are similar in shape to those components of Cunningham's cap, but the Cunningham cap visor is notably different in that it is fashioned from two layers of thin leather. The chinstrap is secured in place with black horn, trouser buttons. A Richards brand, anti-sunstroke cushion was inserted next to the crown by the original owner and remained with the cap after its recovery from the battlefield.[26]

Click this link to navigate to Part II of this study...

Acknowledgments:

I am indebted to numerous institutions, private collections and individuals for the insights and artifacts that they shared for this study. I owe them my gratitude. Their contributions have enables a truly comprehensive study of Confederate caps to be offered to the body of material history.

Institutions:

Library of Congress, notably the Liljenquist collection, Washington DC

Museum Director Pat Ricci and Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana

Museum Curator, Robert Hancock and the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia

CEO Ray Richey and the Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Curator of Textiles Jan Hiester and the Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina

Operations Chief Rachel H. Cockrell, and Curator of Education William J. “Joe” Long and the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina

Curator Mark J. Koziol and the New York State Military Museum, Saratoga Springs, New York

Dr. Gordon L. Jones, Senior Military Historian and Curator and the Atlanta History Center, Atlanta, Georgia

Kentucky Military History Museum, Frankfort, Kentucky

Bardstown Civil War Museum, Munson collection, Bardstown, Kentucky

Registrar Sarah Cohen and the Old State House Museum, Little Rock, Arkansas

Curator W.R. “Willie” Johnson and Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park collection, Kennesaw, Georgia

Curator Paul Shevchuk and Gettysburg National Park collection, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Fort Donelson National Park and Battlefield collection, Dover, Tennessee

Curator Heather Beattie and the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia

Curator Bob Bradley and the Alabama Department of Archives and History collection, Montgomery, Alabama

Florida Photographic Collection, Tallahassee, Florida

Army History and Education Center, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania (formerly the USAMHI)

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Valentine History Center, Richmond, Virginia

North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina

Rosenberg Library, Galveston, Texas

State Archives of Florida, Tallahassee, Florida

US Naval Institution, Annapolis, Maryland

Shenandoah Valley Battlefield Foundation, National Historic District collection, New Market, Virginia, and the Luray Valley Museum, Luray, Virginia; images by Mike Scheibe.

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC

Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia

Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia

Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III collection, Dallas, Texas

Encyclopedia of Arkansas website and Henry Deeks

Private collections:

Gary Hendershott Museum Consultants, Little Rock, Arkansas

The Horse Soldier Military Antiques, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Military Images, Harry Roach and Ron Coddington editors

Lawrence T. Jones, III, Confederate Calendar Works, Austin, Texas

Shannon Pritchard, Old South Military Antiques, Ashton, Virginia

The Alan Hoeweller Trust

Heritage Auctions, Dallas, Texas

Keith Kenerly, Deep South Artifacts, Fredericksburg, Virginia

Will Gorges, Battleground Antiques, New Bern, North Carolina

Roanoke Virginia Antiques

Allen Wandling, Midwest Civil War Relics

Russ Hayes, Volunteer Relics, Clarksville, Tennessee

Brian "Rebel" Akins, Rebel Relics, Gladesville, Tennessee

Glen C. Cangelosi, M.D., WashingtonArtillery.com website

Michael D. Kramer

Dr. Michael R. Cunningham

Rob Golan

Bob McDonald

Images:

Greg Starbuck

Ronnie Townes

The Taylor family

Colonel Paul A. Rockwell

The Louise V. Boone family

Tommy Knox

Kirk D. Lyons

Debra Rounsavall

Fred Slaton

Larry Chapman

William A. Albaugh

J. Dale West

Chris Carroll

The Clint Bryant family

The Frasca collection, CWTI

Vaughan & Jack W. Melton, Jr.

N.D. Lyons & Michael Dan Jones collection

Mrs. Walter B. Hill

Alan T. Parker

Antiques Roadshow

Civil War Canteens, Sylvia and O’Donnell, 2nd Ed 1990, p. 40, Henry Deeks collection

Journey to Pleasant Hill: The Civil War Letters of Captain Elijah P. Petty, Walker’s Texas Division CSA, edited by Norman D. Brown, The University of Texas, Institute of Texas Cultures, San Antonio, 1982, p. xiv

I Held Lincoln: A Union Sailor’s Journey Home, Richard E. Quest, Potomac Books, The University of Nebraska Press, 2018, pages 9, 10 and 37

Conrad Wise Chapman: Artist and Solider of the Confederacy, Ben L. Bassham, The Kent State University Press, 1998

Rebels & Yankees: Fighting Men of the Civil War, William C. Davis, Gallery Books, 1989, p. 204, Fred Slaton collection

Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Louisiana in the Civil War, Carl Moneyhon and Bobby Roberts, The University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville, 1990, p. 104, Larry Chapman collection

Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Arkansas in the Civil War, Bobby Roberts and Carl Moneyhon, The University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville, Arkansas, 1987, p. 38.

Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Georgia in the Civil War, Anne J. Bailey and Walter J. Fraser, The University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville, Arkansas, 1997

Civil War Album, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections (LLMVC), Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Arkansas History Commission, Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas

Echoes of Glory: Arms and Equipment of the Confederacy, edited by Henry Woodhead, Time Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia, 1996

Alan Archambault, artwork

The following individuals and institutions have provided invaluable information from their archives, research and specialized expertise: the Louisiana State University Library, Baton Rouge, Louisiana; the Texas State Library and Archives, Austin, Texas; the Chicago Historical Society, Chicago, Illinois; Lynne Kay Shuffield, United Daughters of the Confederacy, Houston, Texas; Center of American History, University of Texas, Austin, Texas; and, the Director of Genealogical Department W.M. von Maszewski, Fort County Library, Richmond, Texas. The following individuals have provided valuable insights to me on 19th century fabrics: Charles R. Childs, Ben Tart, Pat Kline, Rabbit Goody and Sean Phillips. The scholars whose research has been foundational in this and other Confederate uniform studies include Harold S. Wilson; Thomas M. Arliskas; Leslie D. Jensen; Geoffrey R. Walden; Ron Field; Vicki Betts; Michael Rugeley Moore; C.L. Webster; and Bob Williams.

Finally, I owe my sincere thanks to my mother, Lyn Adolphus Wicke, for the many hours that she spent copy editing all four parts of the cap study.

Copyright: This study and its contents are copyrighted to the Adolphus Confederate Uniforms website with the exception of those images that are part of the Library of Congress collection, or in the public domain.

Bibliography:

[1] Billings, John D., Hardtack and Coffee or The Unwritten Story of Army Life, Boston, George M. Smith & Co., 1887, p. 205, “They [recruits] wore the government clothing as it was furnished them, from the unshapely, un-comely forage cap to the shoddy, inelastic sock.”

[2] National Archives, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, Washington DC, Confederate General Orders No. 9, Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office, Richmond, Va., June 6, 1861, (hereafter, Confederate General Orders with appropriate reference).

[3] Confederate General Orders No. 9, Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office, Richmond, Va., June 6, 1861; and, Confederate General Orders No. 4, War Department, Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office, Richmond, January 24, 1862.

[4] Shuffield, Lynna Kay, Records of the Confederate States Quartermaster Trans-Mississippi Depot at Houston, Harris County, Texas, 1 February 1865 to 22 May 1865, Official Records of the City Secretary of the City of Houston, City Hall Annex, 900 Bagby, Houston, Texas, 2008, (hereafter, Houston QM Clothing Ledger, 1865). Mrs. Anna Russell, City Secretary of the City of Houston provided the archives to the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

[5] Captain Edward C. Wharton; his records of 1861-1864, as Chief Quartermaster/Clothing Bureau, District of Texas, New Mexico & Arizona. National Archives, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, Confederate Inspection Records, M935, Roll 8, 89-J.41 through 158-J.41, Captain Edward C. Wharton, 1862-1864, Chief of Clothing and Equipment Bureau, District of Texas, 141-J.41, Estimate for Clothing, 50,000 men for one year, Gen Order No. 100, Office of the Adjutant General, Richmond, Va., December 1862, (hereafter, the M935, Roll 8 records will be annotated as Wharton with the applicable report number). See also National Archives, Record Group 109, Compiled Service Records of Confederate General and Staff Officers, and Non-Regimental Enlisted Men, M331, Roll 264, E.C. Wharton, reports of 16 Oct 1863 and 29 February 1864 with supplementary comments, (hereafter, Wharton, 16 October 1863; and, Wharton, 29 February 1864).

[6] Artifact courtesy of the American Civil War Museum (Museum of the Confederacy), Richmond, Virginia. The author examined the Barksdale cap on 24 July 2012.

[7] J.B.W. Phillips cap artifact is courtesy of the Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina. The author examined the cap on 11 November 2016. The infantry officer, “souvenir” cap artifact and images are courtesy of Heritage Auctions, Dallas, Texas. The G. Julian Pratt cap artifact and images are courtesy of Gary Hendershott Museum Consultants, Little Rock, Arkansas.

[8] Artifact courtesy of the Alan Hoeweller collection. The author examined the cap on 30 November 2011.

[9] The archival data regarding the manufacture and purchases of North Carolina caps is drawn from the independent research of C.L. Webster. Webster drew on the CSA Citizens M346 files from the following: Albert Cohen, Roll 180; William P. Denny, Roll 240; W.H.C. Lovitt, Roll 602; Joseph Buxbaum, Roll 129; W.H. & R.S. Tucker, Roll 1041; Thomas L. Pugh, Roll 826; Isiaih Prag, Roll 818; Young, Wriston & Orr, Roll 1154. Artifact and images courtesy of the Rob Golan collection.

[10] Artifact and images courtesy of Bob MacDonald; these artifacts may now be part of the Bob Jaffee collection.

[11] Artifact courtesy of the Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina. The author examined the cap on 11 November 2016. CSR South Carolina, M267, Roll 100, R.V. Sweatman, Captain J.T. Kanapaux’s Company, Lafayette Artillery, South Carolina Light Artillery.

[12] Artifact courtesy of the Shenandoah Valley Battlefield Foundation, National Historic District collection, New Market, Virginia. It was on loan to the Luray Valley Museum, Luray, Virginia, and on exhibit there, in 2022 and 2023. Images are courtesy of Mike Scheibe. CSR Virginia, M324, Rolls 225, 341 and 658, Stephen J. Perkins, Private, 2nd Regiment Virginia Artillery; Captain Snead’s Company Virginia Light Artillery, Fluvanna; Company H, 22nd Battalion Virginia Infantry.

[13] Artifact and image courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

[14] Artifact and image courtesy of Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia.

[15] Artifact and image courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

[16] Artifact and image courtesy of the Atlanta History Center, Atlanta, Georgia; the provenance is attributed to Captain Will Hardin, 47th Georgia Infantry, but the service records are inconclusive.

[17] This cap is featured in Echoes of Glory: Arms and Equipment of the Confederacy, Time Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia, 1996, p. 165, erroneously attributed to Captain Robert H. Alexander, Company C, 30th Virginia Infantry. Neither the provenance nor the collection is identified. An image of this cap will be added when it becomes available. See also, CSR M324, R 760. Neither the provenance nor the collection is identified.

[18] Artifact and image courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

[19] Artifact and image courtesy of Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia.

[20] Artifact and image courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

[21] Artifact courtesy of Old South Military Antiques, Ashland, Virginia. The provenance for this cap is sparse. The author examined the cap on 4 December 2011.

[22] Artifact and image courtesy of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

[23] Artifact and image courtesy of Gary Hendershott Museum Consultants, Little Rock, Arkansas.

[24] Artifact and image courtesy of Old South Military Antiques, Ashland, Virginia.

[25] Artifact courtesy of Dr. Michael R. Cunningham. The author examined the cap on 25 July 2013.

[26] Artifact and image courtesy of Gettysburg National Park collection, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Catalog # 17163.

Acknowledgments:

I am indebted to numerous institutions, private collections and individuals for the insights and artifacts that they shared for this study. I owe them my gratitude. Their contributions have enables a truly comprehensive study of Confederate caps to be offered to the body of material history.

Institutions:

Library of Congress, notably the Liljenquist collection, Washington DC

Museum Director Pat Ricci and Confederate Memorial Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana

Museum Curator, Robert Hancock and the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia

CEO Ray Richey and the Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Curator of Textiles Jan Hiester and the Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina

Operations Chief Rachel H. Cockrell, and Curator of Education William J. “Joe” Long and the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina

Curator Mark J. Koziol and the New York State Military Museum, Saratoga Springs, New York

Dr. Gordon L. Jones, Senior Military Historian and Curator and the Atlanta History Center, Atlanta, Georgia

Kentucky Military History Museum, Frankfort, Kentucky

Bardstown Civil War Museum, Munson collection, Bardstown, Kentucky

Registrar Sarah Cohen and the Old State House Museum, Little Rock, Arkansas

Curator W.R. “Willie” Johnson and Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park collection, Kennesaw, Georgia

Curator Paul Shevchuk and Gettysburg National Park collection, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Fort Donelson National Park and Battlefield collection, Dover, Tennessee

Curator Heather Beattie and the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia

Curator Bob Bradley and the Alabama Department of Archives and History collection, Montgomery, Alabama

Florida Photographic Collection, Tallahassee, Florida

Army History and Education Center, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania (formerly the USAMHI)

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Valentine History Center, Richmond, Virginia

North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina

Rosenberg Library, Galveston, Texas

State Archives of Florida, Tallahassee, Florida

US Naval Institution, Annapolis, Maryland

Shenandoah Valley Battlefield Foundation, National Historic District collection, New Market, Virginia, and the Luray Valley Museum, Luray, Virginia; images by Mike Scheibe.

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC

Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia

Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia

Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III collection, Dallas, Texas

Encyclopedia of Arkansas website and Henry Deeks

Private collections:

Gary Hendershott Museum Consultants, Little Rock, Arkansas

The Horse Soldier Military Antiques, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Military Images, Harry Roach and Ron Coddington editors

Lawrence T. Jones, III, Confederate Calendar Works, Austin, Texas

Shannon Pritchard, Old South Military Antiques, Ashton, Virginia

The Alan Hoeweller Trust

Heritage Auctions, Dallas, Texas

Keith Kenerly, Deep South Artifacts, Fredericksburg, Virginia

Will Gorges, Battleground Antiques, New Bern, North Carolina

Roanoke Virginia Antiques

Allen Wandling, Midwest Civil War Relics

Russ Hayes, Volunteer Relics, Clarksville, Tennessee

Brian "Rebel" Akins, Rebel Relics, Gladesville, Tennessee

Glen C. Cangelosi, M.D., WashingtonArtillery.com website

Michael D. Kramer

Dr. Michael R. Cunningham

Rob Golan

Bob McDonald

Images:

Greg Starbuck

Ronnie Townes

The Taylor family

Colonel Paul A. Rockwell

The Louise V. Boone family

Tommy Knox

Kirk D. Lyons

Debra Rounsavall

Fred Slaton

Larry Chapman

William A. Albaugh

J. Dale West

Chris Carroll

The Clint Bryant family

The Frasca collection, CWTI

Vaughan & Jack W. Melton, Jr.

N.D. Lyons & Michael Dan Jones collection

Mrs. Walter B. Hill

Alan T. Parker

Antiques Roadshow

Civil War Canteens, Sylvia and O’Donnell, 2nd Ed 1990, p. 40, Henry Deeks collection

Journey to Pleasant Hill: The Civil War Letters of Captain Elijah P. Petty, Walker’s Texas Division CSA, edited by Norman D. Brown, The University of Texas, Institute of Texas Cultures, San Antonio, 1982, p. xiv

I Held Lincoln: A Union Sailor’s Journey Home, Richard E. Quest, Potomac Books, The University of Nebraska Press, 2018, pages 9, 10 and 37

Conrad Wise Chapman: Artist and Solider of the Confederacy, Ben L. Bassham, The Kent State University Press, 1998

Rebels & Yankees: Fighting Men of the Civil War, William C. Davis, Gallery Books, 1989, p. 204, Fred Slaton collection

Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Louisiana in the Civil War, Carl Moneyhon and Bobby Roberts, The University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville, 1990, p. 104, Larry Chapman collection

Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Arkansas in the Civil War, Bobby Roberts and Carl Moneyhon, The University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville, Arkansas, 1987, p. 38.

Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Georgia in the Civil War, Anne J. Bailey and Walter J. Fraser, The University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville, Arkansas, 1997

Civil War Album, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections (LLMVC), Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Arkansas History Commission, Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas

Echoes of Glory: Arms and Equipment of the Confederacy, edited by Henry Woodhead, Time Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia, 1996

Alan Archambault, artwork

The following individuals and institutions have provided invaluable information from their archives, research and specialized expertise: the Louisiana State University Library, Baton Rouge, Louisiana; the Texas State Library and Archives, Austin, Texas; the Chicago Historical Society, Chicago, Illinois; Lynne Kay Shuffield, United Daughters of the Confederacy, Houston, Texas; Center of American History, University of Texas, Austin, Texas; and, the Director of Genealogical Department W.M. von Maszewski, Fort County Library, Richmond, Texas. The following individuals have provided valuable insights to me on 19th century fabrics: Charles R. Childs, Ben Tart, Pat Kline, Rabbit Goody and Sean Phillips. The scholars whose research has been foundational in this and other Confederate uniform studies include Harold S. Wilson; Thomas M. Arliskas; Leslie D. Jensen; Geoffrey R. Walden; Ron Field; Vicki Betts; Michael Rugeley Moore; C.L. Webster; and Bob Williams.

Finally, I owe my sincere thanks to my mother, Lyn Adolphus Wicke, for the many hours that she spent copy editing all four parts of the cap study.

Copyright: This study and its contents are copyrighted to the Adolphus Confederate Uniforms website with the exception of those images that are part of the Library of Congress collection, or in the public domain.

Bibliography:

[1] Billings, John D., Hardtack and Coffee or The Unwritten Story of Army Life, Boston, George M. Smith & Co., 1887, p. 205, “They [recruits] wore the government clothing as it was furnished them, from the unshapely, un-comely forage cap to the shoddy, inelastic sock.”

[2] National Archives, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, Washington DC, Confederate General Orders No. 9, Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office, Richmond, Va., June 6, 1861, (hereafter, Confederate General Orders with appropriate reference).

[3] Confederate General Orders No. 9, Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office, Richmond, Va., June 6, 1861; and, Confederate General Orders No. 4, War Department, Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office, Richmond, January 24, 1862.

[4] Shuffield, Lynna Kay, Records of the Confederate States Quartermaster Trans-Mississippi Depot at Houston, Harris County, Texas, 1 February 1865 to 22 May 1865, Official Records of the City Secretary of the City of Houston, City Hall Annex, 900 Bagby, Houston, Texas, 2008, (hereafter, Houston QM Clothing Ledger, 1865). Mrs. Anna Russell, City Secretary of the City of Houston provided the archives to the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

[5] Captain Edward C. Wharton; his records of 1861-1864, as Chief Quartermaster/Clothing Bureau, District of Texas, New Mexico & Arizona. National Archives, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, Confederate Inspection Records, M935, Roll 8, 89-J.41 through 158-J.41, Captain Edward C. Wharton, 1862-1864, Chief of Clothing and Equipment Bureau, District of Texas, 141-J.41, Estimate for Clothing, 50,000 men for one year, Gen Order No. 100, Office of the Adjutant General, Richmond, Va., December 1862, (hereafter, the M935, Roll 8 records will be annotated as Wharton with the applicable report number). See also National Archives, Record Group 109, Compiled Service Records of Confederate General and Staff Officers, and Non-Regimental Enlisted Men, M331, Roll 264, E.C. Wharton, reports of 16 Oct 1863 and 29 February 1864 with supplementary comments, (hereafter, Wharton, 16 October 1863; and, Wharton, 29 February 1864).